The school library has the potential to contribute greatly to the success of a school. A library and qualified teacher librarian can support teachers and students to enhance their practice and learning through interventions, specialist programs, and collaboration. Brown and Malenfant (2017) identify five key areas that can enhance student success: library instruction, library use, collaboration, literacy instruction, and research consultation. Scholastic (2016) presents similar themes that enhance student learning: a credentialed school librarian, collaboration and co-teaching, technology access, and collection size. Even though these results are from America, there are similar findings across Australia. ALIA and Freedom of Access to Information and Resources The impact of great school libraries report 2016 outlines three crucial drivers that underpin school library practices and that also underpin the Australian Curriculum. These drivers include; reading, digital literacy, and critical thinking and research (ALIA, 2016).

School libraries are in a position to assist schools in enhancing various education outcomes necessitated by the Australian Curriculum. Of the General Capabilities, school libraries can address: Literacy, ICT Capability, Critical and Creative Thinking, Ethical Understanding, and even Intercultural Understanding through the material delivered and curated, and Personal and Social Capability through the teaching of self-management and goal setting while working through inquiry tasks. Additionally, the Cross-Curriculum Priorities can be addressed through the careful and intentional selection of resources that meet various organising ideas. I recently completed ETL503 whereby I was required to curate a selection of resources that meet a wide range of organising ideas within the Asia and Australia’s Engagement with Asia priority. This is a relevant and easy way to meet these requirements while alleviating the pressure from classroom teachers. I recently used this concept to present a range of novels to the Head of English for his consideration when selecting appropriate texts for the Year 8 Literature Circles assessment.

Despite substantial evidence identifying the positive impact a qualified teacher librarian has on student achievement, D’agata (2016) outlines many teacher librarians feel unsupported and frustrated due to a lack of professional collaboration with various stakeholders or groups within the school structure. D’agata (2016) specifically identifies the barriers some teacher librarians have encountered when attempting to collaborate with teaching staff; including, attitudes, roles and schedules. These barriers need to be overcome through advocacy and leadership. Schools must be able to see the teacher librarian at work and be present and active in the school community. Kemp (2017) suggests ten ways to promote the position and includes enhancing student literacy outcomes as a top priority. As experts in this area, teacher librarians can work to develop staff and student confidence in their literacy skills and to enhance these skills. Embedding an Academic Reading program is one such way to promote the importance of literacy and comprehension skills and to encourage co-teaching and collaboration with teaching staff. Embedding literacy programs across the school by ensuring the skills and texts are relevant and timely rather than bolt-on programs that simply teach the skills without context have been found to be most effective.

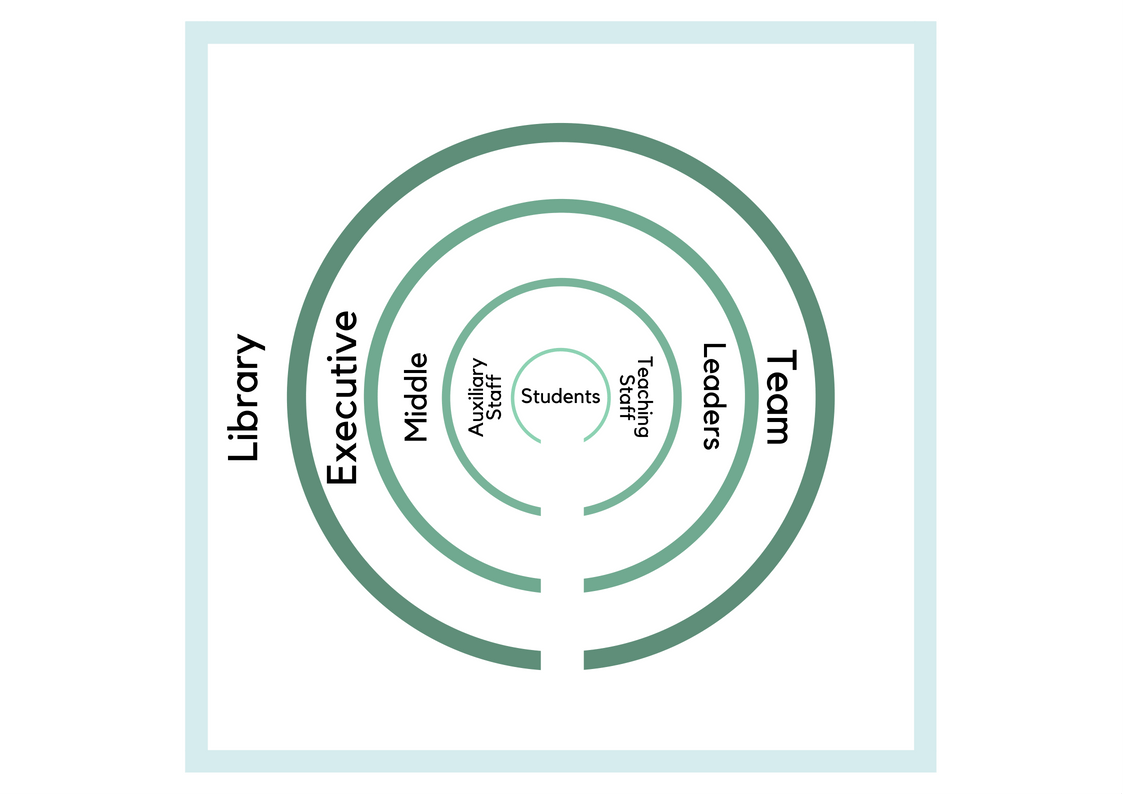

A school structure can both help and hinder the success of a school library. If outdated structures or perceptions of the library are in place, then school libraries will encounter many barriers preventing them from engaging effectively with the school community. While Cascio (2003) suggests 21st workplace organisation is shifting from “vertically integrated hierarchies to networks of specialists”, a school structure is a complex combination of a vertical hierarchy with elements of a web-like network. This makes illustrating or mapping a school structure difficult. There are many ways to go about this. The structure could be mapped in terms of big-picture decision-making and leadership or impact on learning. Below, I have chosen to illustrate how the library hugs the different elements of the school structure. The library and librarian lead from the side and from within by supporting the entire school community. I have also demonstrated a simplified illustration of the hierarchical levels in terms of impact on other levels. In this instance, the Executive Team sit above the Middle Leaders but also infiltrate all levels of the school structure, as do all other elements.

References

Australian Library and Information Association. (2016). The impact of great school libraries report 2016. Retrieved from https://fair.alia.org.au/sites/fair.alia.org.au/files/u3/Great%20Australian%20School%20Libraries%20Impact%20Report.pdf

Brown, K., & Malenfant, K. J. (2017). Academic library impact on student learning and success: Findings from assessment in action team projects. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/issues/value/findings_y3.pdf

Cascio, W. F. (2003). Changes in work, workers and organizations. In W. C. Borman, D. R. Ilgen & R. J. Klimoski (Eds.), Handbook of psychology: Industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 401-422). Retrieved from Proquest Ebook Central.

D’agata, G. (2016). Teachers + School Librarians = Student Achievement: When Will We Believe It? UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 2659. http://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations/2659

Kemp, J. (2017). Ten ways to advocate for your role as a teacher librarian. Connections, 103(4), 6-7. Retrieved from https://www.scisdata.com/connections

Scholastic. (2016). School libraries work: A compendium of research supporting the effectiveness of school libraries. 2016 edition. Retrieved from http://www.scholastic.com.au/assets/pdfs/school-libraries-work.pdf

[Reflection: Module 2.1b]