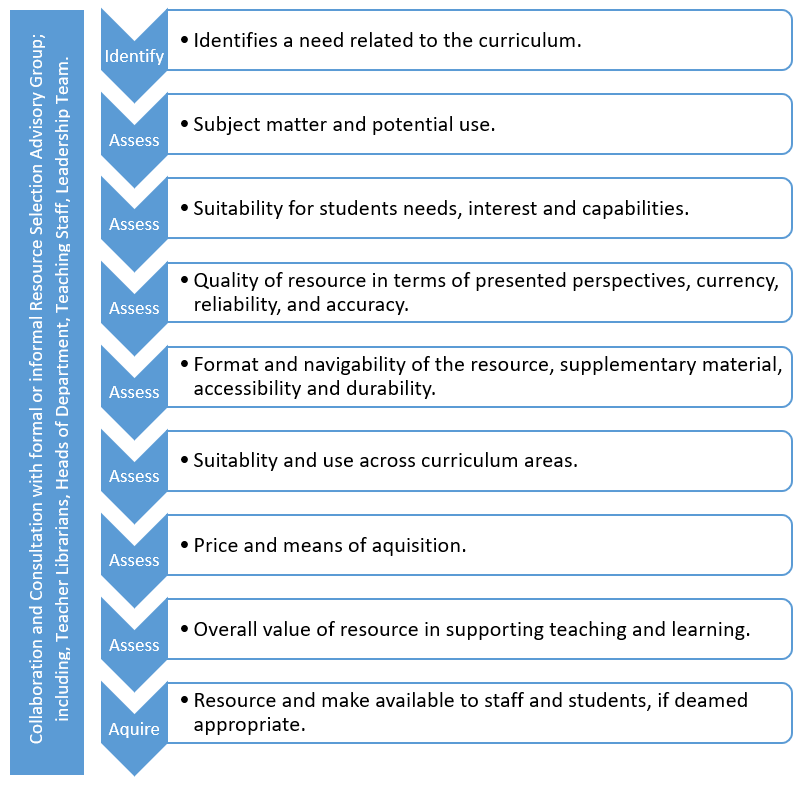

The selection model developed by Hughes-Hassell and Mancall incorporates a simplistic view of resource evaluation and selection (2005). A model or framework that allows more flexibility to align with different circumstances may be more appropriate in meeting the needs of school libraries. More comprehensive resource selection criteria are outlined by the New South Wales Department of Education, which includes a range of evaluative questions to assess the appropriateness of potential resources (2017). These questions range from potential use of the resource to scope, quality, durability and price (New South Wales Department of Education, 2017). Additionally, the Queensland Department of Education provides a set of four selection criteria, which include; resource appropriateness for target audience, information accuracy and currency, suitability and relevance for the curriculum, and student outcomes (2012). Underpinning a decision-making model should be collaboration and consultation throughout all stages. As identified by the Australian School Library Association, Teacher Librarians must collaborate with their colleagues in a range of situations to evaluate the effectiveness of practices and resources in enhancing the outcomes of students (2014). Specifically, “Highly accomplished teacher librarians work co-operatively with staff to develop, recommend, organise and manage appropriate print and online resources to support student learning” (2014, p.11). As such, I have developed a draft selection decision-making model that will developed over time, as I am sure my understanding of this topic will expand.

Draft Selection Decision-Making Model

References

Hughes-Hassell, S., & Mancall, J. C. (2005). Collection management for youth: responding to the needs of learners. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.csu.edu.au

New South Wales Department of Education. (2017). Choosing resources: Criteria for choosing resources: Curriculum materials. Retrieved from https://education.nsw.gov.au/teaching-and-learning/curriculum/learning-across-the-curriculum/school-libraries/teaching-and-learning/information-skills/resources/choosing-resources

Queensland Department of Education. (2012). Collection development and management. Retrieved from http://education.qld.gov.au/library/support/collection-dev.html

[Reflection: Module 2.1]