When taking research literacy lessons, I have the students conduct a basic Google search using their inquiry question. Then, in a new tab, they use only the key words and watch what happens to the number of results. Next, they use a range of Boolean operators with their key words. We compare and discuss the change in the number of results (usually significantly less) and the power of effective search skills. I always point out that despite everyone in the room using the exact same words and operators, we get a different number of results. We speak about Google’s algorithms, it’s filtering of their results, and the power of going beyond page 1. This has always been a valuable discussion point, as some believe the filter bubble can dramatically increase confirmation bias. In a climate of divisive viewpoints, this is important to note. Not only in the personal and social world but also the world of academia. Students must have the opportunity to challenge their thinking to develop deeper understandings and develop their capacity for critical thinking.

In his 2011 TED Talk, Pariser highlighted the need for algorithms to be transparent and customisable to enhance companies’ ethics and “civic responsibility” in terms of how people connect and with what they are exposed to (TED2011, 2011). It seems Google responded. When recently searching in Google, I wanted to see if I could turn off certain algorithms or data collection – could I go back to square one to have a truly pure and uncorrupted search experience. It turns out, in 2018, Google released Your Data in Search which makes deleting your search history and controlling the ads you see much easier. You can also turn off Google’s personalisation. While some studies suggest Google’s attempt at reducing the filter bubble (searching in private mode and when signed out) does not greatly affect the disparity between users’ search results, it is perhaps a step in the right direction. It is worthwhile noting that Google disputes the claim that personalisation greatly effects search results.

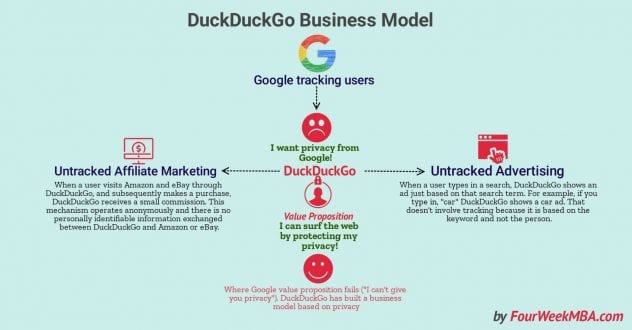

The jury may still be out as key players are unsurprisingly at odds, however I have seen the difference in results first hand when working with classes of students. In the realm of their academic research, it may not be as big of an issue as say perpetuating political beliefs or other ideologies, however these algorithms are deciding what it deems most useful or important for these students. This can limit students’ search rather than assist, and popularised click bait can hinder their academic as well as social searching. An alternative search engine, which does not track or store your personal information, is DuckDuckGo. A search engine many librarians and educators have been promoting for some time. The next time I take a research literacy lesson, I will put it to the test and see how it stacks up against Google.

Cuofano, G. (n.d.). DuckDuckGos Business Model [Image]. Retrieved from https://fourweekmba.com/duckduckgo-business-model/

So, the next topic to explore is appropriate collective curation tools that support students inside and outside the school environment.

Reference

TED2011. (2011, March). Eli Pariser: Beware online “filter bubbles” [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/eli_pariser_beware_online_filter_bubbles?language=en#t-476026

O’Reilly. (2008, September 19). Web 2.0 Expo NY: Clay Shirky (shirky.com) It’s Not Information Overload. It’s Filter Failure [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LabqeJEOQyI

[Reflection: Module 2.5]