Digital literacy and digital citizenship describe the key skills and dispositions of 21st century citizens. It is essential students develop these capacities within the context of 21st century learning to live and work effectively in and beyond school. As shown in Figure 1, digital learning environments [DLEs] provide the structural support for 21st century pedagogy to build digital citizenship and other 21st century skills (Keane & Keane, 2013). Digital citizenship, including digital literacy, must be embedded across the curriculum for it to be contextualised and therefore relevant, authentic, and sustainable (Earp, 2018). Ultimately, schools need to create DLEs that support deep learning across the curriculum and prepare students for life and work.

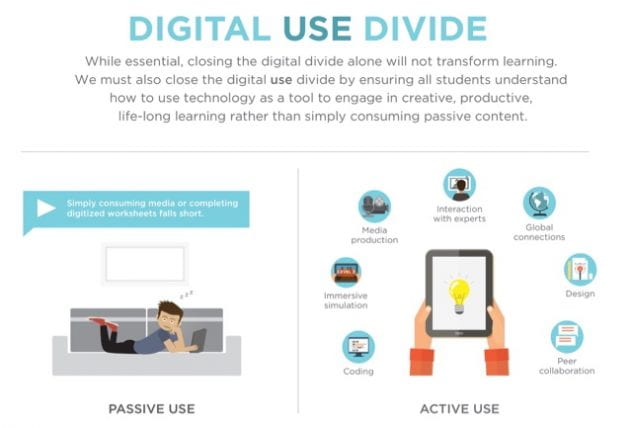

A challenge in developing DLEs is to ensure information and communication technologies [ICTs] are used in transformative ways. Two common problems I have seen with ICT integration are overuse and passive use. Overuse includes the tendency of ICT-integrated lessons to become what Gonzalez (2016) calls “Grecian Urns”. Such lessons focus on the product over educational value. In the context of ICTs, the technology becomes the focus and deep learning is lost. While some functional or operational gains may be made, opportunities to develop digital citizenship and deep learning related to the curriculum are lost. ICT is also commonly used as a passive substitute for paper, with similar effects – loss of deep learning opportunities. ICTs should be used to support knowledge construction and help students develop critical and creative thinking, communication, and collaboration skills. As seen in Figure 2, the American Department of Education (2017) refers to the issue of passive use as the “digital use divide”. It is important to leverage ICTs in transformative ways to allow for in-depth application of digital citizenship practices and deep learning (Keane & Keane, 2013). This also creates the opportunity to connect to students’ third space and build digital citizenship in more authentic and meaningful ways (Harrison, 2019a; Harrison 2019b).

Over the course of ETL523, my thinking has been extended and challenged. I have always held a firm belief in the critical role of technology in supporting the 21st century needs of students; however, the way this has translated to my practice has evolved over time and will continue to evolve having now taken this subject. The concept of digital citizenship in all its guises sits very well with me. The ability for students to create and consume information in ways that enrich their experiences and the experiences of others is powerful. I have been inspired to consider how my use of ICTs in teaching can extend the learning beyond the classroom walls through local and global collaboration. I am challenging myself this year to connect with experts or other schools using Skype in the classroom and Microsoft Teams to extend the communication and collaboration portals of my classroom.

The role of TLs has always been inherently servant-based leadership but, as I have noted in several reflections in the past, it is more than that. TLs work as instructional leaders and transformational leaders to guide the entire school community in developing their skills and inspire the community to delve deeper into effective teaching and learning practices. Fullan (2013) explains the key drivers to change as capacity building, collaborative work, pedagogy, and systemness supported through professional learning communities. He says “people are motivated by good ideas tied to action” (Hargreaves & Fullan, 2012, p.7). As a TL, I can use my position to lead from the middle to garner support for the prioritisation and ongoing development of our DLE. Already this term, the library team has developed an online professional learning space for teachers, with the intention to build communities of practice across the college. Once teachers see the power of the DLE in their own learning, this might transfer to their classrooms. As TLs are change leaders, we are well-positioned to support the school in developing effective policy and environments to support the whole school community and enhance student learning outcomes (Johnston, 2012).

References

Department of Education United States of America. (2017). Reimagining the role of technology in education: 2017 national education technology plan update. Retrieved from https://tech.ed.gov/files/2017/01/NETP17.pdf

Earp, J. (2018, November 21). Curriculum integration of digital citizenship. Retrieved from https://www.teachermagazine.com.au/articles/curriculum-integration-of-digital-citizenship

Fullan, M. (2013). Maximising leadership for change [Participant booklet]. Retrieved from https://michaelfullan.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/14_AU_Final-Workbook_web.pdf

Gonzalez, J. (2016, October 30). Is your lesson a Grecian urn? [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://www.cultofpedagogy.com/grecian-urn-lesson/

Hargreaves, A., & Fullan, M. (2012). Professional capital: Transforming teaching in every school. New York, NY: Teacher’s College Press.

Harrison, N. (2019a, March 13). Reflection: Module 1.0a. Digital learning environments [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/nharrison/2019/03/13/reflection-module-1-0/

Harrison, N. (2019b, March 24). Reflection: Module 2.2. Digital fluency and third space [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/nharrison/2019/03/24/reflection-module-2-2/

Johnston, M. P. (2012). School librarians as technology integration leaders: Enablers and barriers to leadership enactment. School Library Research, 15. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/

Keane, W. & Keane, T. (2013). Deep learning, ICT and 21st century skills: Leading for education quality [Conference paper]. Retrieved from https://researchbank.swinburne.edu.au/file/ae199457-ab1e-4787-ac72-9844c8a0214a/1/PDF%20%28Published%20version%29.pdf

World Economic Forum. (2015). New vision for education: Unlocking the potential of technology. Retrieved from http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEFUSA_NewVisionforEducation_Report2015.pdf

[Assessment 3 Part B Critical Reflection]