Reflection

This subject has highlighted the importance of effective teamwork and leadership in schools. While servant leadership is characteristic of teacher librarians (TLs), I have come to understand my own leadership style as much broader. The combination of instructional and transformational leadership, known as leadership for learning (Dempster et al., 2017), resonates with me as TLs are first and foremost teachers who work with others to drive teaching and learning improvement (Herring, 2007). This leadership style is often associated with principalship; however, it has strong connections with the roles of a TL. TLs easily address each of the dimensions of leadership for learning through their participation in; ongoing professional development of self and others, networking opportunities, teaching and learning, and evidenced-based practice.

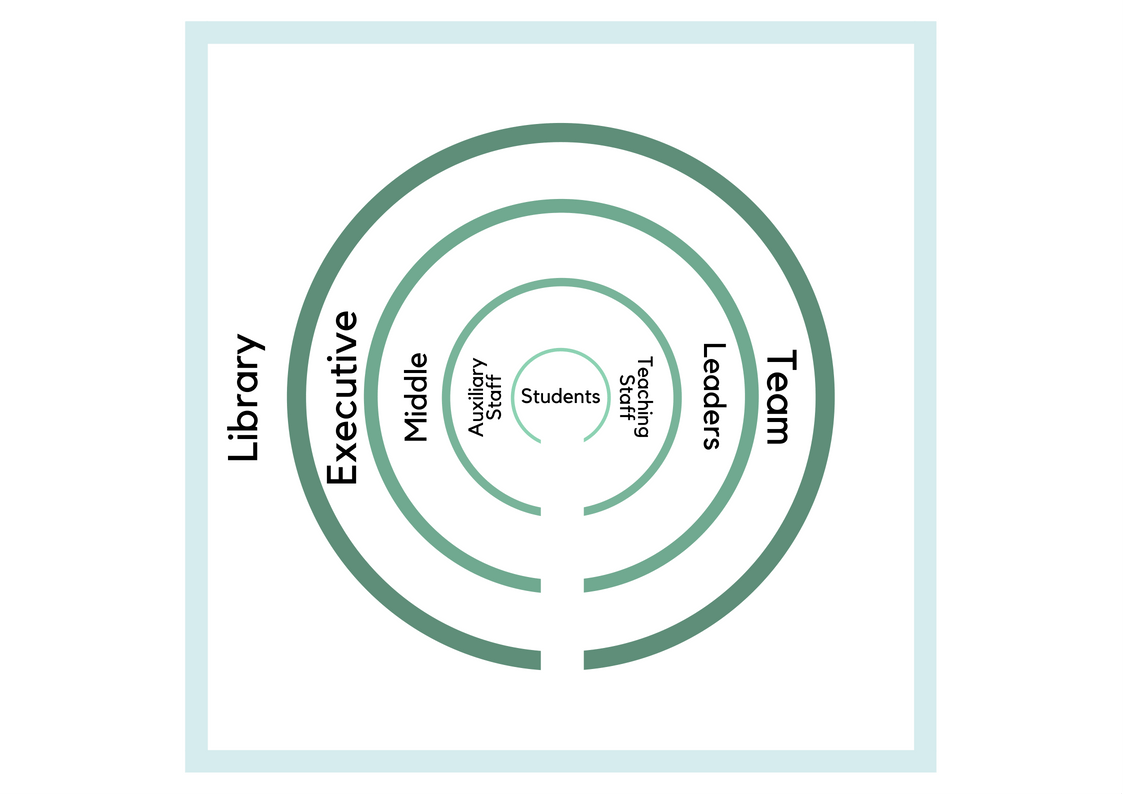

The middle leadership position of a TL enables them to be both a leader and constituent. This dichotomy develops trust and collegiality through reciprocal relationships and mutual respect (Harrison, 2018a). This reminded me of the adage “I must follow them, for I am their leader” (Rosthorn, 2016). I feel this neatly encompasses the humility and reciprocity needed of effective teams and leaders. This sets the precedent for leadership of a shared moral purpose and demonstrates the dynamic nature of middle leadership.

Through the case study work, collaboration was challenging due to conflicting commitments and levels of participation. At times, I lead the group response, while other times I stepped back to let others take a leadership role. Collaboration is integral to successful teamwork; therefore, I attempted to inspire collaboration through questioning to engage the conversation and team. While this was not always successful, I believe it demonstrated my intention to create a sense of collegiality. Collaboration between colleagues is crucial in schools, as it breaks down barriers that isolate teachers, increases visibility of leaders (particularly TLs), and opens dialogue to test theories and draw on a range of expertise (Griffin, Bui, & Care, 2013; Harrison, 2018b). This sharing also leads to enhanced student outcomes through team commitment and motivation (Rajhans, 2012). The teamwork skills required of the group work were also reflected in the case studies themselves. Throughout the case studies, it was clear the Director of Information Services required teamwork and leadership skills to improve the department dynamic and performance outcomes of the libraries (Group 4, 2018a; Group 4, 2018b). Foremost, effective communication was consistently needed to enable a collaborative culture and improve conflict management. This positive workplace environment leads to enhanced efficiency and productivity (Aramyan, 2015), which is integral to the service nature of school libraries.

The difficulties experienced during the case studies, while at times unique to the online environment, mirror communication difficulties or passiveness and complacency in the workplace. There is much evidence to suggest complacency is the enemy of success, particularly in the changing education landscape (Ballantyne, 2016). Technology and growing information landscapes can threaten job security if complacency reigns. TLs as leaders must be at the forefront of innovation in education to contribute to the development of lifelong learners. This requires a plethora of knowledge, skills, behaviours, and dispositions to demonstrate leadership, grit and perseverance (Moreillon, 2018). Leadership for learning acutely encompasses these characteristics while inspiring commitment and action through the formation of shared purpose and strong professional relationships.

References

Aramyan, P. (2015, October 8). 5 ways workplace communication effectiveness can increase productivity [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://explore.easyprojects.net/blog/5-ways-workplace-communication-effectiveness-can-increase-productivity

Ballantyne, R. (2016, June 30). Complacency ‘killing Australian education’. The Educator Australia. Retrieved from https://www.theeducatoronline.com/au/news/complacency-killing-australian-education/218721

Dempster, N., Townsend, T., Johnson, G., Bayetto, A., Lovett, S., & Stevens, E. (2017). Leadership and literacy: Principals, partnerships and pathways to improvement. Retrieved from Proquest Ebook Central.

Griffin, P., Bui, M., & Care, E. (2013). Understanding and analysing 21st-century skills learning outcomes using assessments. In R. Luckin, S. Puntambekar, P. Goodyear, B. L. Grabowski, J. Underwood, & N. Winters (Eds.), Handbook of design in educational technology (pp. 53-64). Retrieved from Proquest Ebook Central.

Group 4. (2018a, August 3). Group 4 case study 3 [Online forum comment]. Retrieved from https://interact2.csu.edu.au/webapps/discussionboard/do/message?action=list_messages&course_id=_32450_1&nav=discussion_board_entry&conf_id=_58831_1&forum_id=_130876_1&message_id=_1928007_1

Group 4. (2018b, September 8). Group 4 case study 4 [Online forum comment]. Retrieved from https://interact2.csu.edu.au/webapps/discussionboard/do/message?action=list_messages&course_id=_32450_1&nav=discussion_board_entry&conf_id=_58831_1&forum_id=_130879_1&message_id=_1980778_1

Harrison, N. (2018a, July 28). Reflection: Module 2.3 [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/nharrison/2018/07/28/module-2-3-reflection/

Harrison, N. (2018b, September 1). Reflection: Module 4.2 [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/nharrison/?s=constituent#.W7LOkBMzbOQ

Herring, J. (2007). Teacher librarians and the school library. In S. Ferguson (Ed.) Libraries in the twenty-first century: Charting new directions in information (pp.27-42). Retrieved from Elsevier ScienceDirect Books Complete.

Moreillon, J. (2018, February 26). Grit, complacency, and passion [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://www.schoollibrarianleadership.com/2018/02/26/grit-complacency-and-passion/

Rajhans, K. (2012). Effective organizational communication: A key to employee motivation and performance. Interscience Management Review, 2(2), 81-85. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/d74f/ce848669ba68f7a8929a9ec1a108758a98b9.pdf

Rosthorn, A. (2016, December 15). There go the people. I must follow them. Tribune magazine. Retrieved from http://www.tribunemagazine.org/2016/12/i-must-follow-them-for-i-am-their-leader/

[Assessment 2 Part B: Reflective Practice]