The ability to read and interpret information is a fundamental skill needed to participate fully in the world. These basic skills (although actually quite complex) will continue to be as important, if not more, than the past. The information-rich world is expanding; however, algorithms are filtering the information we see. So, people’s values and beliefs are consistently reinforced, while other perspectives are left out or buried on page 3 of Google search results – an equally ominous fate. In turn, this leads to confirmation bias, which can be detrimental to those who cannot critically evaluate what they are experiencing and reading.

Algorithms present users with a calculated selection of “relevant” information; however, it is clear that users must develop and employ the necessary skills to work within these algorithms. The top search results are not always the most useful. Searchers must not ignore the other titbits of information such as Google’s snippets displayed under each search result. While Google can change the snippet from the meta description of the webpage to their own algorithmically determined snippet (Silver Smith, 2013), it is still a useful port of call that many searchers skip over. This allows savvy searchers to preliminarily assess the relevance and worth of the search results – which are not always at the top of the page (Wineburg & McGrew, 2017). But algorithms are not the only cause of confirmation bias. Ashrafi-Amiri & Al-sader (2016) suggest searchers’ assumptive search queries based on fact retrieval and verification will characteristically retrieve more bias results than if the query were non-assumptive; that is, knowledge acquisition, comparative, analytical, and exploratory in nature. Information literacy instructors must be aware of this and consider this when developing instruction for students.

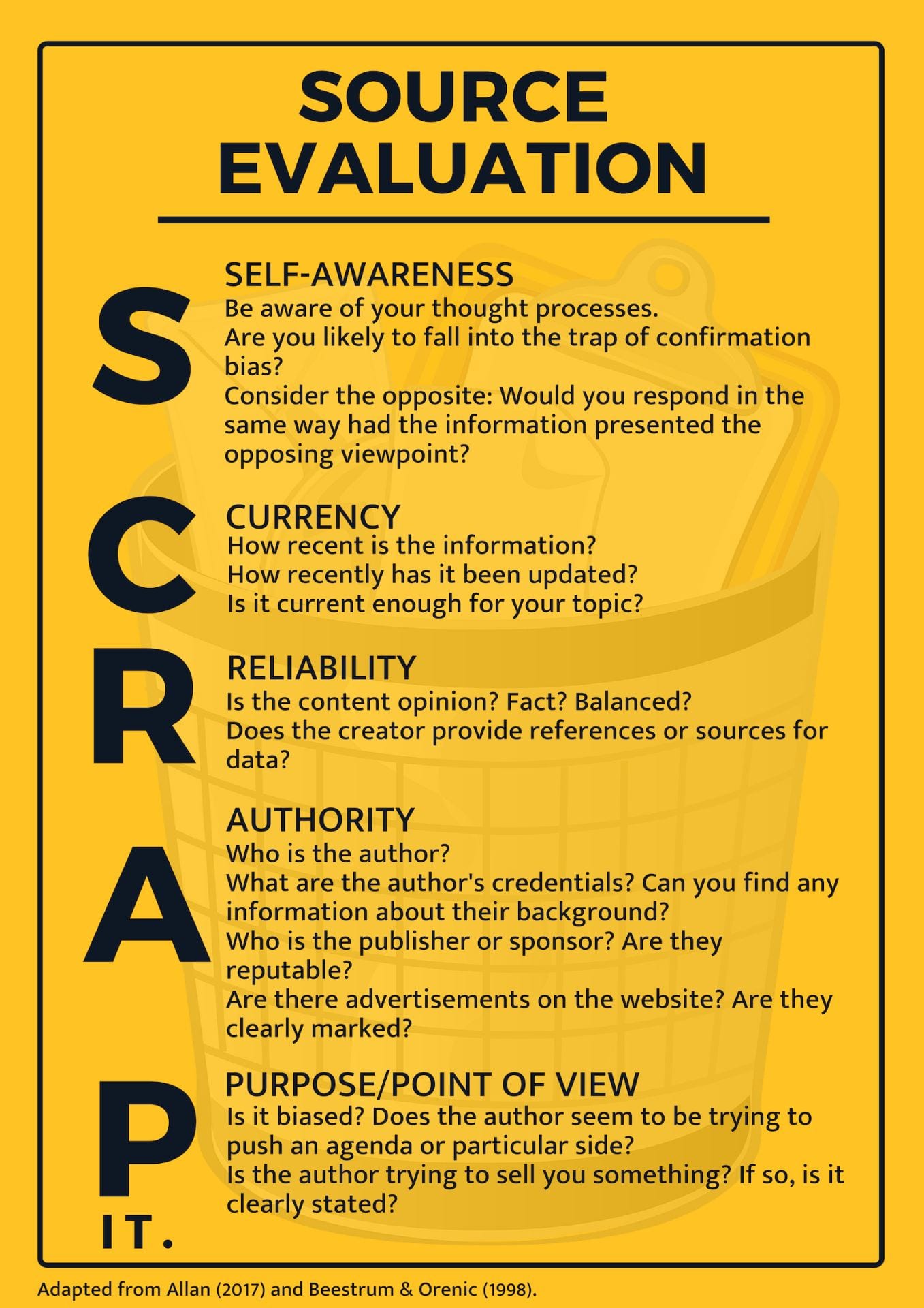

TLs must address the critical thinking skills required to work with and within algorithms that reinforce bias. Maynes (2015) identifies the role of information literacy instructors in explicitly teaching students about the forms of bias, ways to identify their own bias, and skills to mitigate the potential effects of their bias. This involves teaching the metacognitive skills students need to not only know the strategies to use but how, when and why to use them (Maynes, 2015). A combination of lateral and vertical reading is useful in all information evaluation situations. While many libraries utilise a CRAP (Currency, Reliability, Authority, Purpose/Point of View) test to step students through the information evaluation process, other steps can also be considered so students tune into their metacognition and identify their bias (Wineburg & McGrew, 2017). Allan (2017) suggests incorporating some form of personal reflection into the information literacy sessions offered to students. Students must not only be taught that confirmation bias exists, they must also be taught the skills to identify it in themselves and to deal with it when it occurs. One such strategy is to identify when a source of information elicits an emotional response from the reader – Does it make you happy? Sad? Reinforce? Challenge? Developing self-regulation triggers the reader to seek additional information and reflection to consider the opposite or alternate (Hirt & Markman, 1995; Lord, Lepper, & Preston, 1984; Mussweiler, Strack, & Pfeiffer, 2000). This requires information searchers to reflect on their reactions at each step and consider whether their evaluation of the usefulness or credibility of the source would be the same if it presented the opposing viewpoint. Deliberately considering the opposing viewpoint requires the searcher to consider their bias and the bias of others. This is a powerful strategy in unveiling subconscious or hidden bias. Allan (2017) posits adding an S (Self-examination or Self-awareness) to the beginning of the CRAP test would highlight the importance of identifying and recognising cognitive and confirmation bias.

The importance of slowing down the information evaluation process by thinking effortfully and deliberately (Kahneman, 2011) and evaluating laterally (Wineburg & McGrew, 2017) is central to 21st century information and digital literacy. Evaluating laterally requires searchers to seek and consider context and perspective, which means they must seek additional information. Slowing down does not simply mean taking longer to read the article and its parts – it means careful and deliberate consideration and slowing your judgement by first taking your bearings and exploring laterally. This may mean to first leave the site or visit the About Us section to find out more about the author or the organisation, before navigating back to the original source (Wineburg & McGrew, 2017). Thinking laterally can occur in multiple stages of the CRAP test, particularly when assessing the reliability and purpose/point of view present in the source. Searchers will need to explore other sites to learn more about the information. While searchers will not always slow down and employ lateral reading, it is important to know when to slow down. High stakes situations where the searcher may possess a strong bias already or where the information may have significant consequences for the searcher or others, or a highly contested issue or topic may require more deliberate reasoning to ensure the searcher is acquiring balanced, truthful information (Maynes, 2015). Considering the opposite is another practical strategy to employ in these situations.

It is clear that information evaluation and digital literacy skills need to evolve with changing demands and issues within the information landscape. Information literacy instructors must stay abreast of these changes and adapt evaluation strategies as needed. A start might be to model and incorporate lateral reading into existing strategies and follow Allan’s (2017) suggestion and put that S at the beginning of CRAP.

References

Allan, M. (2017). Information literacy and confirmation bias: You can lead a person to information, but can you make him think? Informed Librarian Online, 2017(5). Retrieved from https://asu-ir.tdl.org/handle/2346.1/30699

Ashrafi-Amiri, N. & Al-sader, J. (2016). Effects of confirmation bias on web search engine results and a differentiation [Thesis]. Retrieved from https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/43564372.pdf

Hirt, E.R., & Markman, K.D. (1995). Multiple explanation: A consider-an-alternative strategy for debiasing judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(6), 1069– 1086.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Lord, C. G., Lepper, M. R., & Preston, E. (1984). Considering the opposite: A corrective strategy for social judgment. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 47(6), 1231-1243.

Mussweiler, T., Strack, F., & Pfeiffer, T. (2000). Overcoming the inevitable anchoring effect: Considering the opposite compensates for selective accessibility. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26(9),1142–1150.

Silver Smith, C. (2013). Influencing how Google displays your page description. Retrieved from https://www.practicalecommerce.com/influencing-how-google-displays-your-page-description

Wineburg, S. & McGrew, S. (2017). Lateral reading: Reading less and learning more when evaluating digital information [Report]. Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3048994