REFLECTION

As a High-Impact Teaching Strategy (State of Victoria, 2017), this collaborative project not only extended my understanding of the content, it importantly expanded my Personal Learning Network (PLN) and Personal Learning Environment (PLE) by working with new colleagues across a range of new platforms. Our group worked within a connectivist learning framework to adapt to challenges, grow our networks, and learn from our diversity.

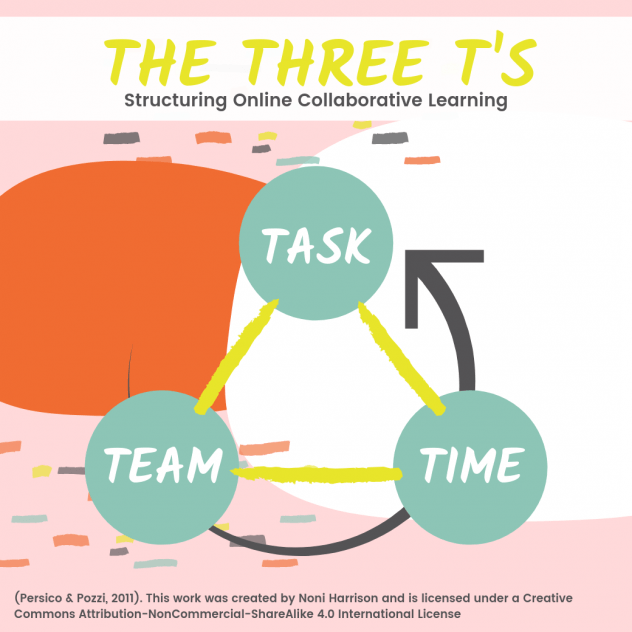

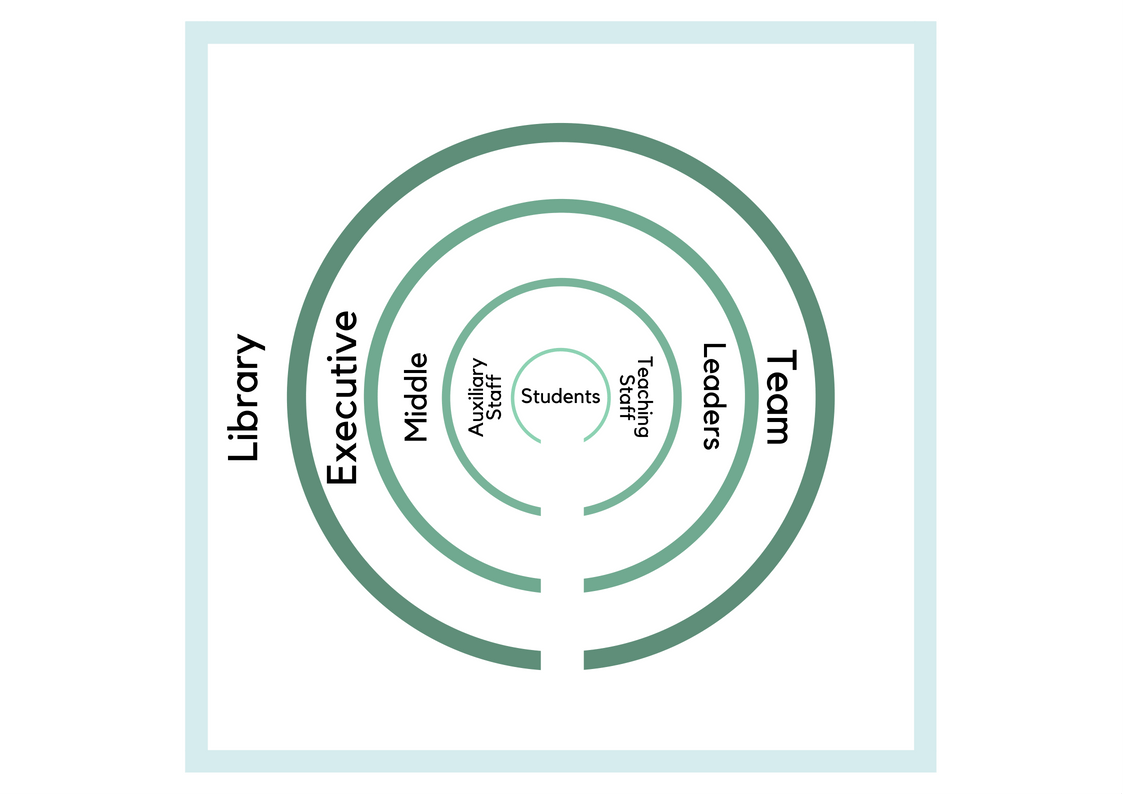

The three intertwined elements of online collaborative learning [OCL] were certainly at play throughout this assessment piece; tasks, teams, and time [see image below] (Persico & Pozzi, 2011). The provided content scheme allowed flexibility with interpretation, execution and mode of output. Additionally, the autonomy in group formation enabled us to work with like-minded people with different skills and experiences. Our diversity (primary teacher, middle school teacher, and teacher librarians within Australia and in the United Arab Emirates) and ability to collaborate in a digital learning environment [DLE] afforded us the opportunity to share, teach, and learn from one another in a deep and unique way.

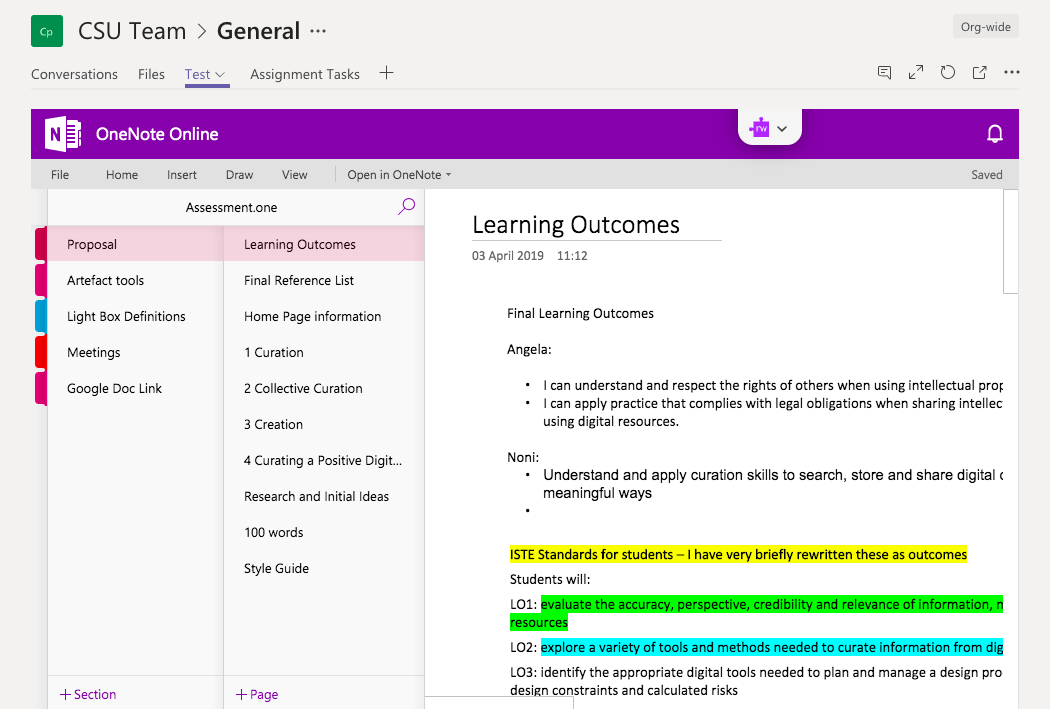

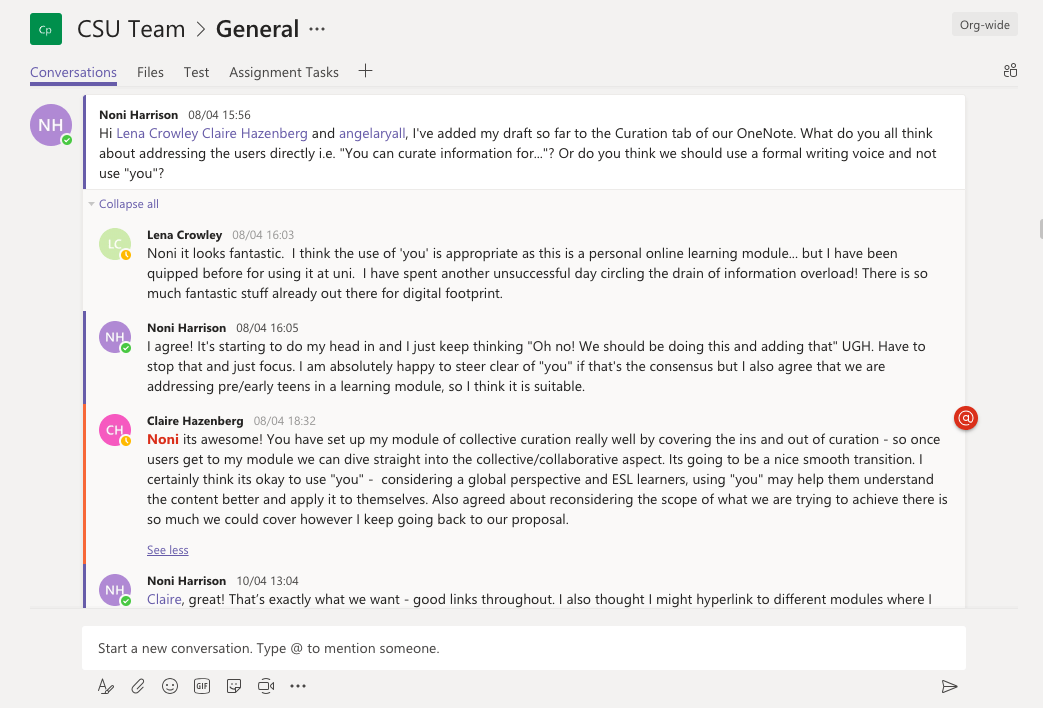

Our modes of communication included Zoom and Microsoft Teams, which allowed synchronous and asynchronous interaction and removed the barriers of working within three different time-zones. Synchronous communication allowed real-time collaboration, while asynchronous communication allowed each group member extended think-time to develop deep reasoning (Aviv, 2000; Duderstadt, Atkins, & Van Houweling, 2002). We used Zoom meetings to prepare for the task and clarify our purpose and roles, while Teams’ Conversation and OneNote were used to discuss progress and share findings. This ensured our communication was transparent and reviewable. This was particularly helpful for me, as I was able to revisit our discussion to clarify my perceptions and it enabled group connection even as our level of synchronous communication dwindled.

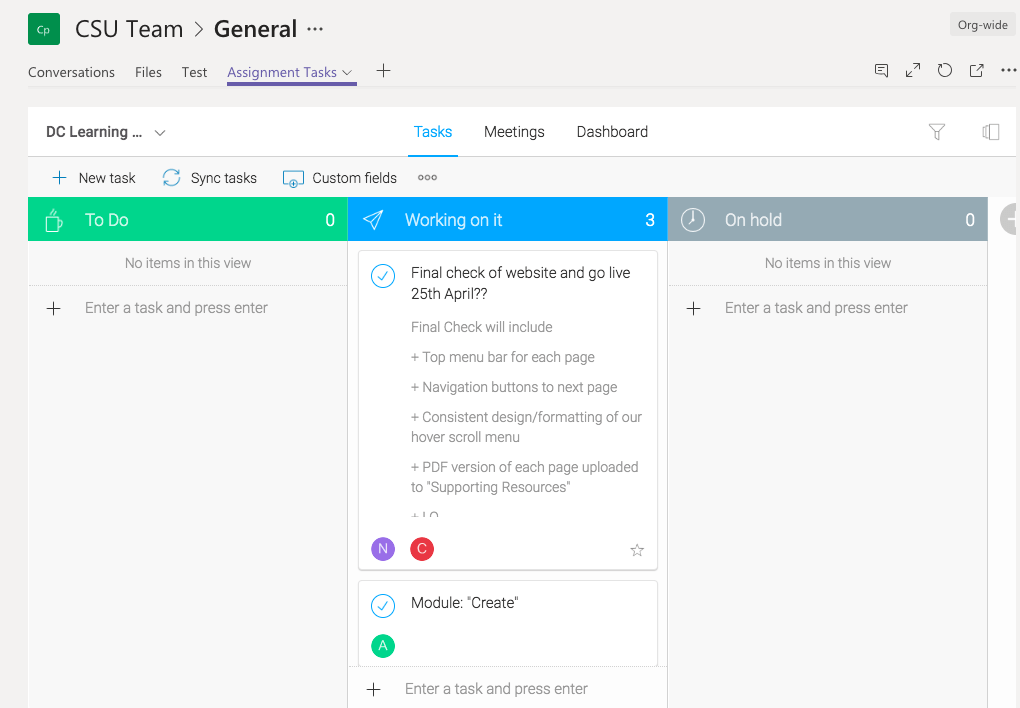

While the group established set phases and schedule, our timing was flexible to allow each group member to work around their other commitments. This worked well for us; however we experienced some difficulties when unintentionally editing the Wix site simultaneously. Luckily, we used Teams’ Conversation to overcome this. We also used Tasks-in-a-Box to assign tasks and due dates. In future, I would use this more effectively by collaboratively breaking the assessment task up into more stages earlier in the planning process. This would enhance the clarity and consistency of our approach. Scheduling another Zoom meeting may have also helped us to realign with our initial goals in real-time to ensure clear perception.

Reimann (2018) identifies three challenges of group work; unequal participation, lack of awareness, and stratified learning zones. While I believe our group avoided these through effective use of online communication and collaboration tools, these are common scenarios I experience with students in school learning environments. Unequal participation is the most common challenge among my students, as collaboration competes with their preference for individualistic reward (Dool, 2010). I believe a shared vision and group roles can be established through the OCL norm of “purpose” to motivate and empower learners. I will ensure the design of future OCL activities include a clear purpose and direct students to establish goals and roles before starting. Strengthening this area will build student capacity to work collaboratively in DLEs.

Having students co-create a digital product and collaborate online with others in their school and beyond, in a similar manner to this task, redefines the parameters of learning through transformative use of technology. This higher end of the SAMR spectrum strengthens connections to students’ third-space, which increases relevancy and learning. The ability of OCL projects to span curriculum areas, address multiple general capabilities, and provide real-world experiences highlights their value. To incorporate global OCL into my teaching, I will take advantage of Asia-Europe Foundation’s yearly school collaborations.

RESOURCES

This experience has enabled me to create a range of resources that will be useful independently and within the full learning module. I wanted to challenge myself and use a range of tools to produce a high-quality, interactive and participatory product. I used the following tools to create my artefact and embedded resources:

-

- Adobe Premiere Pro to create and edit the video

- Adobe After Effects to create animations

- A Power Soft Free Online Screen Recorder to screencast

- Canva to construct infographics and posters

- Diigo Group

- Padlet

- Pixabay and BenSound for visual and auditory elements

- WireWax to construct interactive hotspots

EMBEDDED RESOURCES

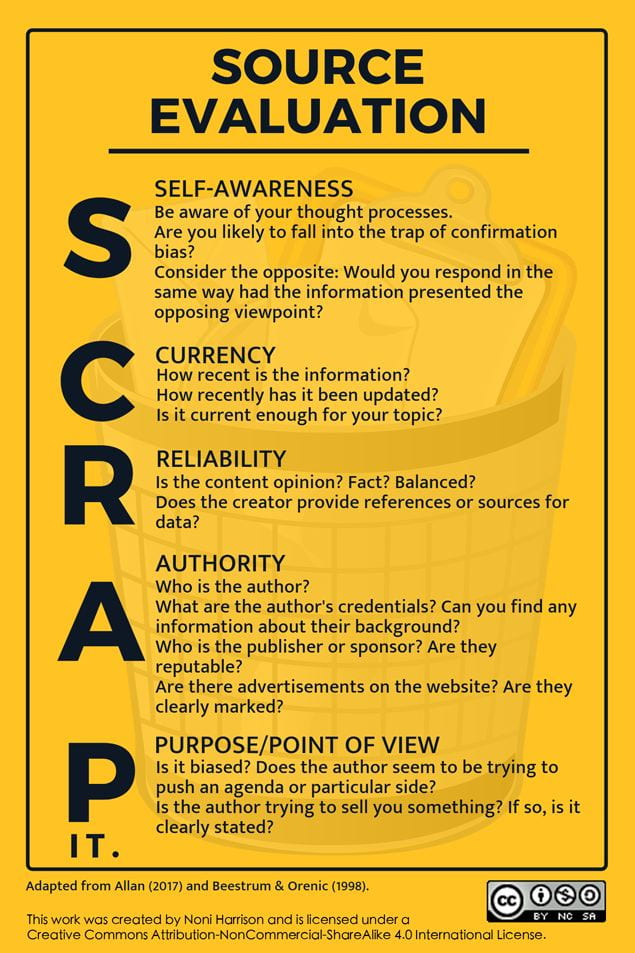

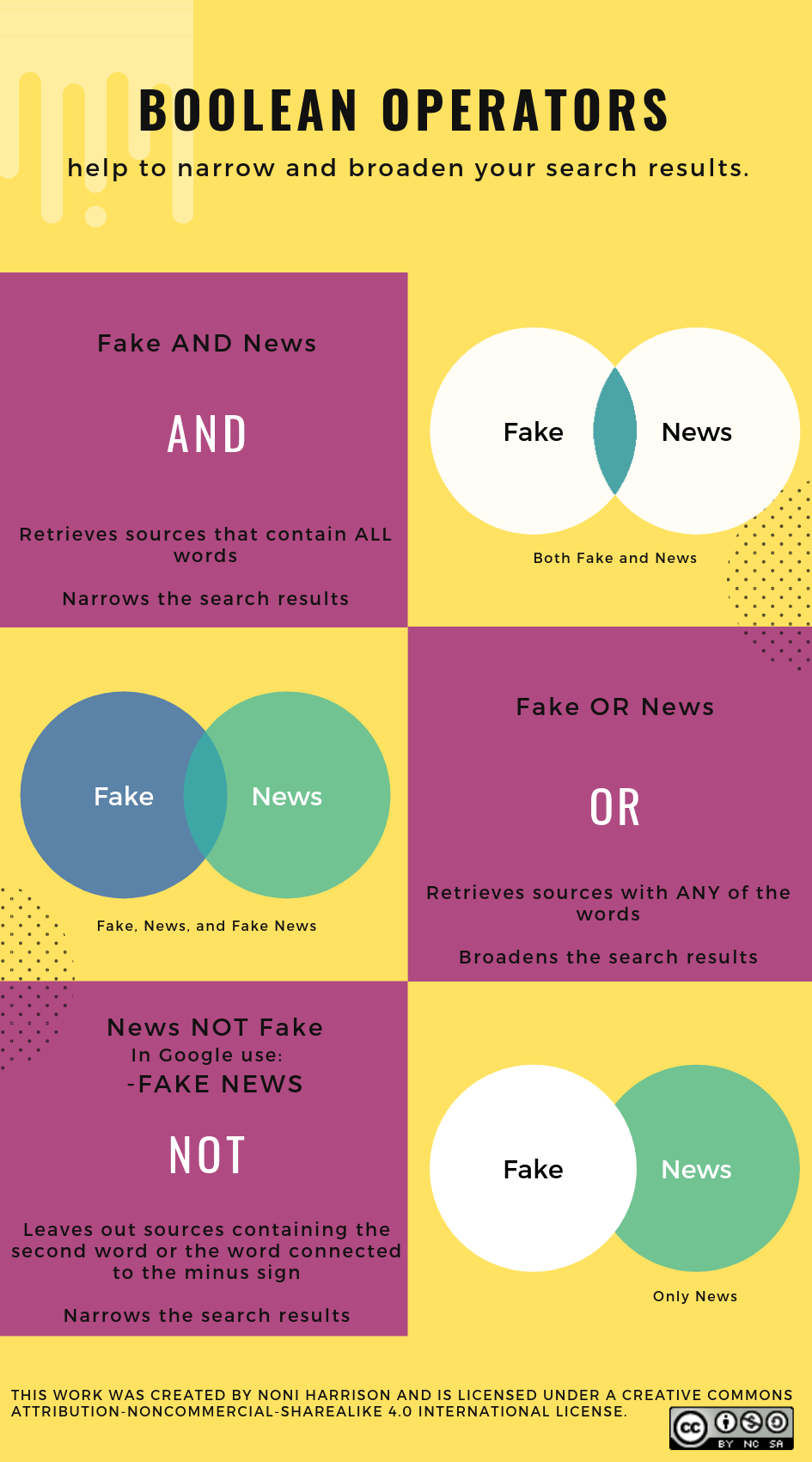

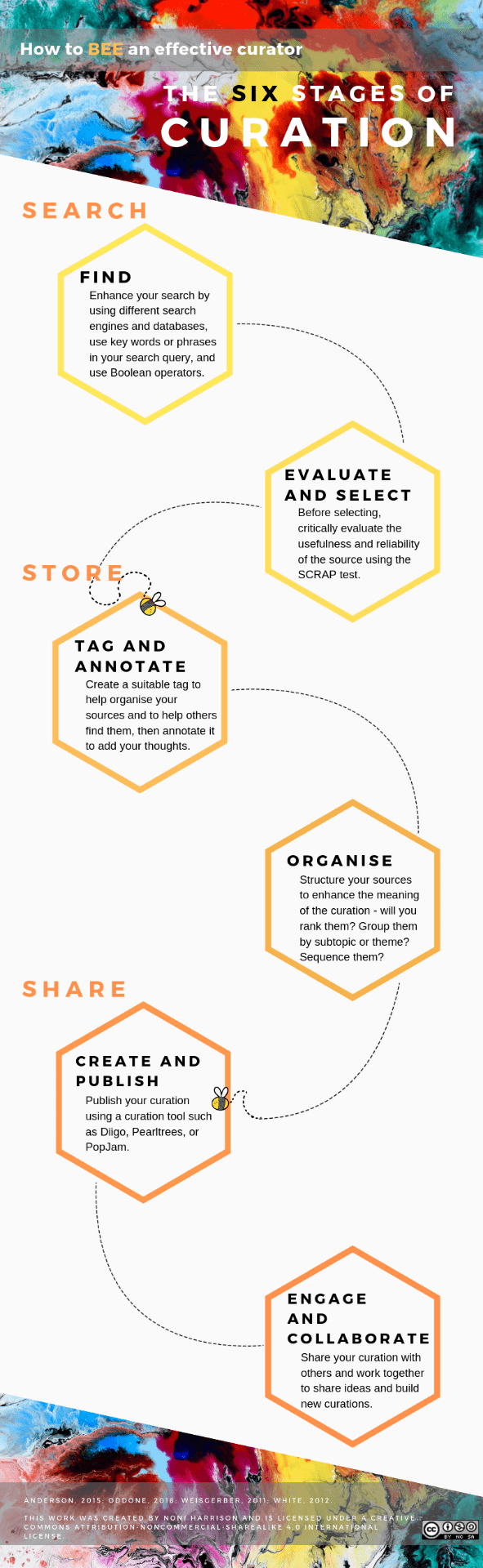

Below are the visual resources I created using Canva.

The screencast tutorial I created to provide instruction on tagging and annotating in Diigo (as seen below) was made using A Powersoft Free Online Screen Recorder, Adobe After Effects and Adobe Premiere Pro, and music from BenSound.

ARTEFACT

The above resources are all embedded in the artefact that I created for the online learning module using WireWax, (as seen below).

References

Asia-Europe Foundation. (2019). 2019 school collaborations. Retrieved from http://www.asef.org/index.php/projects/themes/education/4600-asef-classnet-online-collaborations-2019

Aviv, R. (2000). Educational Performance of ALN via Content Analysis. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Network, 4(2). doi:10.24059/olj.v4i2.1901

Dool, R. (2010). Teaming across borders. In Ubell, R. (Ed.), Virtual teamwork: Mastering the art and practice of online learning and corporate collaboration (pp. 161-192). Retrieved from ProQuest Ebook Central

Duderstadt, J. J., Atkins, D. E., & Van Houweling, D. (2002). Higher education in the digital age: Technology issues and strategies for American colleges and universities. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group.

General capabilities in Australian curriculum: Version 7.5. (2018). Retrieved from the Australian Curriculum and Assessment Authority website: https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/general-capabilities/

H.L. (2017, October 30). SAMR model: A practical guide for edtech integration [Blog post]. https://www.schoology.com/blog/samr-model-practical-guide-edtech-integration

Lindsay, J. (2015). Norms of online global collaboration [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from https://www.slideshare.net/julielindsay/norms-of-online-global-collaboration

Persico, D. & Pozzi, F. (2011). Tasks, teams and time: Three T’s to structure CSCL processes. In Pozzi, F., & Persico, D. (Eds), Techniques for fostering collaboration in online learning communities: Theoretical and practical perspectives (pp. 1-14). doi:10.4018/978-1-61692-898-8

Reimann, P. (2018). Making online group-work work: Scripts, group awareness and facilitation. Retrieved from https://research.acer.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1338&context=research_conference

State of Victoria. (2017). High Impact Teaching Strategies: Excellence in teaching and learning. Retrieved from http://www.education.vic.gov.au/Documents/school/teachers/support/highimpactteachstrat.docx

[Assessment 2 Part C Reflective Blog Post]