I have recently come across a Podcast called We’re starting a cult hosted by yoga-instructor and comedy writer Alexis Novak and ex-pastor turned atheist Barak Hardley. They explore different cults around America and discuss what aspects of those cults they would adopt to create their own. It is very tongue-in-cheek; however, they explore different leadership styles and the power of persuasion involved in the realisation of a cult and the practices or strategies involved in retaining cult members. Despite touting that a positive aspect of cults is a sense of community and common vision and mission, Novak and Hardley (2018) also identify that this level of sameness comes under a much higher position of power and authority of the cult leader. Bass and Steidlmeier (1999) refer to the concept of degrading morality and exploitive leadership as pseudotransformational leadership. While this is not a desirable style of leadership, particularly for a school context, is it interesting to note the potential influence held by a leader and the power that comes with that. Gardner (2014) expresses that leadership is often distinct from power and authority but it can encompass one or both elements at a given point. Leaders may not possess power in the form of extensive organisational decision-making but rather power over others that persuades and convinces. A person does not need to be in a position of power or authority to lead. They can lead and inspire change at any level or setting. Gardner (2014) also emphasises the reciprocal relationship between leader and what he refers to as constituent rather than follower. Effective transformational and instructional leadership styles appear to share this trait of collaboration and emphasise staff professional and personal development, which may decrease the potential of one sole, power-orientated leader. Instructional leadership is particularly interesting in that these leaders develop a clear vision and mission with which to aim (University of Washington, 2015). While, transformational leaders design strategies to motivate the team to set and reach higher goals (Mitchell, 2018).

Would transformational leadership be best suited to organisations needing to introduce change, while instructions leadership would be most effective to lead the team after this evolution has occurred? Or are there multiple settings within which these styles would flourish? At this stage, I don’t think a transformational leadership style is only suitable for introducing and working through change. I think it could be effective in multiple settings.

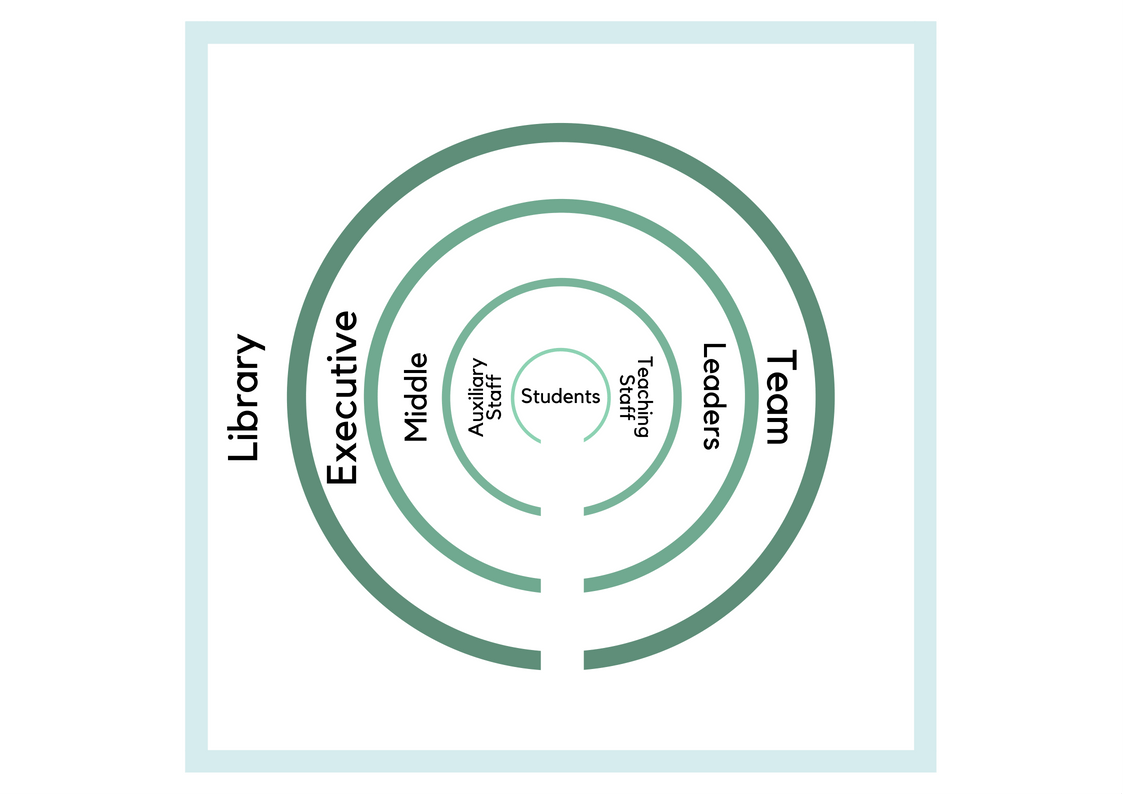

Within an organisational structure, the manager and leader may form two distinct roles; however, they can also be combined. Managers are concerned with the daily functioning of a department and other organisational functions; whereas, leaders persuade constituents to follow by empowering them and entrusting them with different levels of responsibility. Gardner (2014) suggests managers require an organisational structure within which to work; however, leaders do not require an organisation. In an organisational structure such as a school, I believe leaders require effective managerial skills to meet assigned goals and requirements from curriculum, pedagogical, and school levels. Meeting these targets requires careful negotiating of resources as well as leadership capabilities to guide the team toward these goals.

After reading the article Teacher perspectives of ‘effective’ leadership in schools by Moir, Hattie and Jansen (2014), I have a clearer idea of where transformational and instructional leadership styles sit in the school context. Transformational leadership isn’t, as first thought, just about supporting big organisational change. It seems this form of leadership would work well for a teacher librarian (TL) who is engaged with the changing information landscape and who supports the teaching and learning needs of a dynamic 21st century-orientated school context. The “culture of risk taking and innovation” (Moir, Hattie & Jansen, 2014, p. 36) that is characteristic of a transformational leader fits well with the role of the TL and is explicit in Standard 3.3 of the Standards of Professional Excellence for Teacher Librarians (Australian School Library Association, 2004). Instructional, or pedagogical, leadership then seems to suit the position of a principal, as they are in a position to develop the school mission and support positive teaching practice school-wide in order to promote learning outcomes (Moir, Hattie & Jansen, 2014). There are multiple leadership styles that could be used in either position; however, after reading several articles it appears these two leadership styles are preferred among academics and practitioners to garner support, foster a discourse of collegiality and collaboration, address organisation changes, and support student learning.

References

Bass, B. M., & Steidlmeier, P. (1999). Ethics, character, and authentic transformational leadership behavior. Leadership Quarterly, 10(2), 181-217. doi: 10.1016/S1048-9843(99)00016-8

Gardner, J.W, (2013). The nature of leadership. In M. Grogan (Ed.), The Jossey-Bass reader on educational leadership (3rd ed., pp. 17-27). Retrieved from Proquest Ebook Central.

Mitchell, R. M. (2018). Enabling school structure and transformational school leadership: Promoting increased organizational citizenship and professional teacher behavior. Leadership and Policy in Schools. doi: 10.1080/15700763.2018.1475577

Moir, S., Hattie, J. & Jansen, C. (2014). Teacher perspectives of ‘effective’ leadership in schools. Australian Educational Leader, 36(4), 36-40. Retrieved from http://www.minnisjournals.com.au/acel/

Novak, A. & Hardley, B. (Hosts). (2018, May 14). The Rajneeshpuram. We’re starting a cult: A podcast by Alexis Novak and Barak Hardley [Audio Podcast]. Retrieved from http://itunes.apple.com

University of Washington. (2015). 4 dimensions of instructional leadership. In Center for Educational Leadership. Retrieved from http://info.k-12leadership.org/4-dimensions-of-instructional-leadership

[Reflection: Module 2.3]