Evidenced-based practice should not only drive pedagogical initiatives of classroom teachers, it should also be at the core of the work of teacher librarians. Evidence can be used to identify a need or problem, plan and implement initiatives, and evaluate and reflect on those programs. It can also be used to justify library initiatives and programs, budgetary and staffing requirements, and a range of other resourcing needs. That being said, when evidence is gathered by the practitioner for advocacy purposes, the trustworthiness of the evidence and its interpretation comes into question. Therefore, it is vital evidence gathering practices are holistic and incorporate a range of methods.

Vertical and horizontal data sets can help schools better understand their students’ learning journey, while considering their specific context. Data is easily interpreted in a myriad of ways and can be manipulated to suit purpose. It becomes an issue when data is used to compare school performance, rather than focusing on individual student progression. The focus must be on student learning outcomes rather than outcomes. Therefore, vertical data gathered from high-stakes testing should be used in conjunction with horizontal data that provides a more holistic picture of students’ learning levels (Renshaw, Baroutsis, van Kraayenoord, Goos, & Dole, 2013).

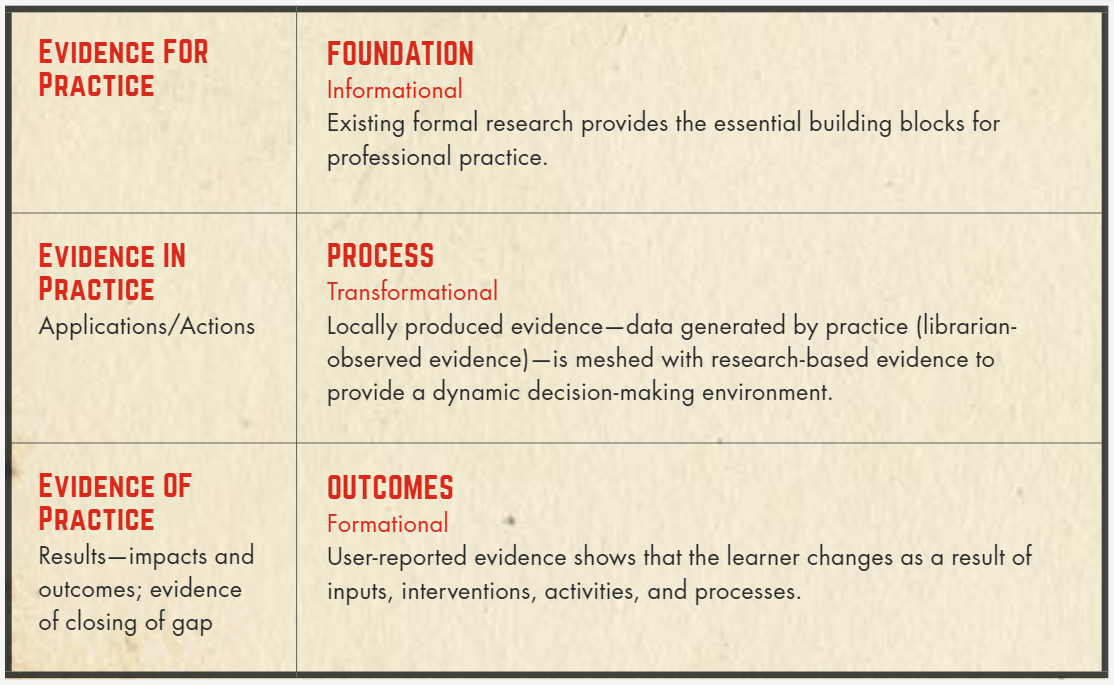

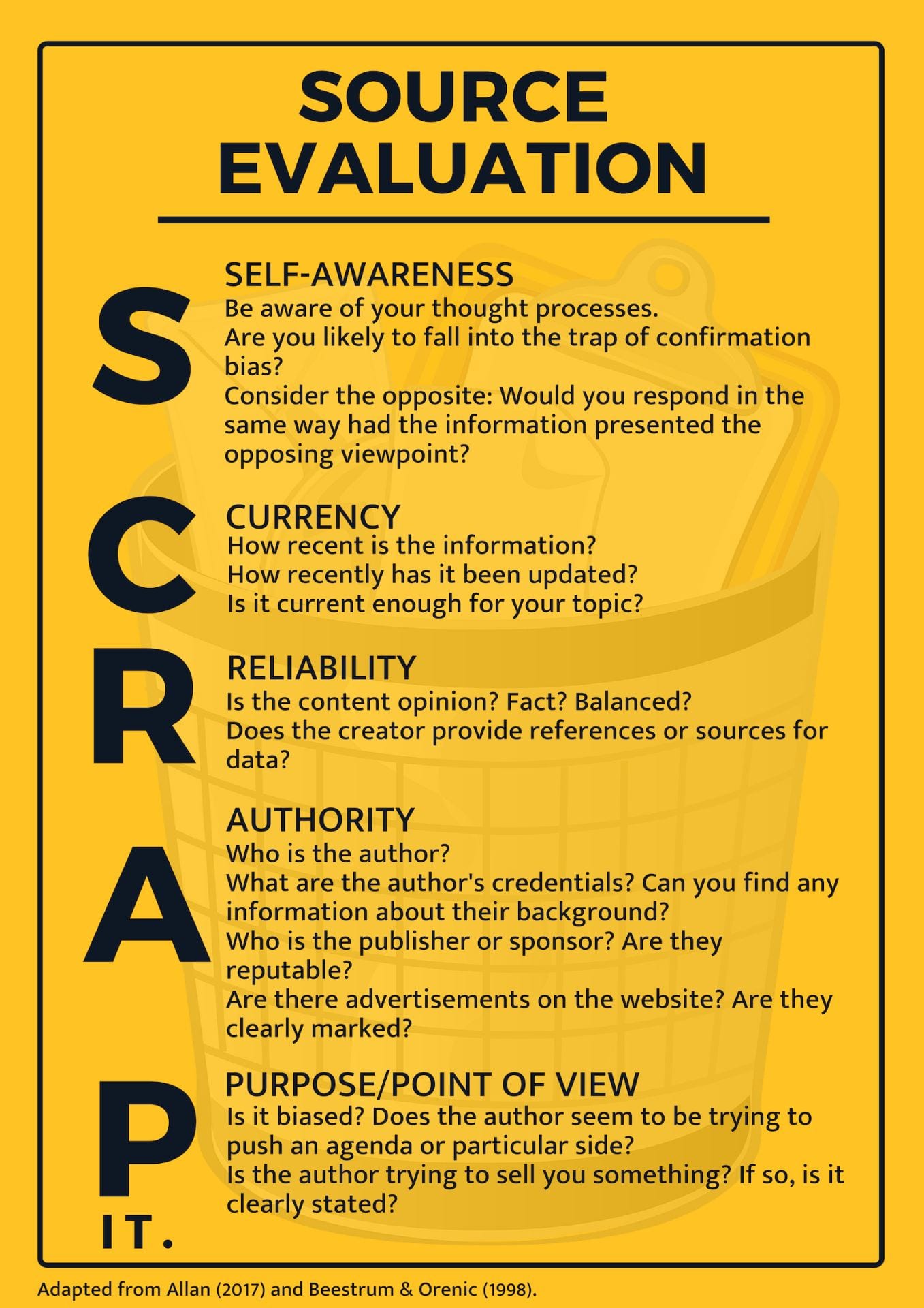

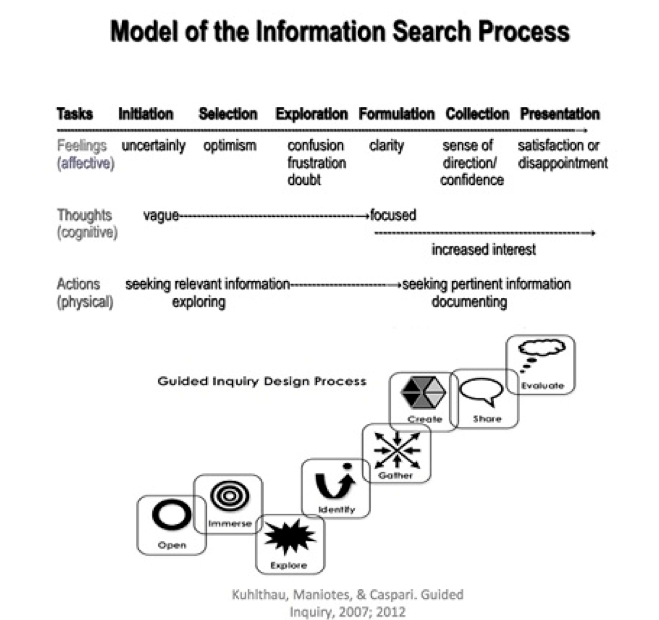

Teacher librarians adopt a holistic approach to evidence-based practice by considering the whole school with which they serve and by drawing on a range of evidence in a range of ways (Gillespie, 2013). As seen in Figure 1, Todd (2015) proposes a holistic model for school libraries, which includes evidence for practice (Foundational: informational), evidence in practice (Process: transformational), and evidence of practice (Outcomes: formational). Furthermore, Robins (2015) highlights the usefulness of action research as part of a holistic approach to collect qualitative and quantitative data and connect educational research with improved practice. Oddone (2017) provides an overview of action research for school libraries as seen in Figure 2.

Gillespie (2013) found that teacher librarians gather evidence through two key modes; by engaging and encountering. The nature of evidence-based practice is therefore not linear. Teacher librarians gather evidence through purposeful and accidental encounters, which involves research-based and/or practitioner-based evidence and application for improved practice through a combination of intuition and reflection (Gillespie, 2013). As with improvement in any field, particularly education, reflection is key to driving improvement as it provides the metacognitive prompts to interpret evidence and consider the practitioner’s professional experience and expertise that is needed to apply evidence meaningfully.

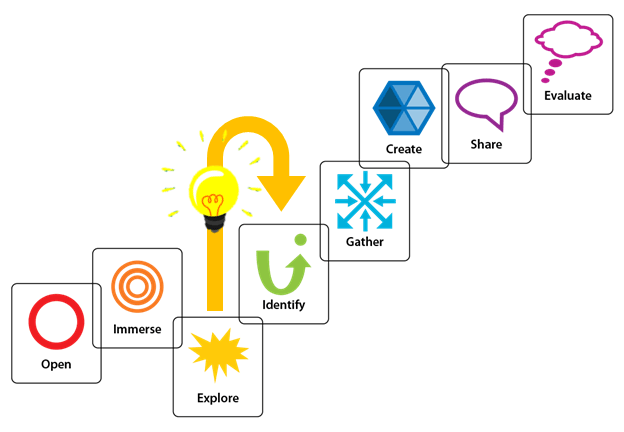

Teacher librarians can utilise evidence-gathering tools to gather evidence for, in and of practice. Gillespie (2013) recommends valuable evidence is drawn from and used within three areas; including, teaching and learning, library management, and professional practice. A tool such as School Library Impact Measure (which I spoke about in my final assessment for ETL504) equips teacher librarians with a framework to assess the impact of their instruction on student learning outcomes during a Guided Inquiry experience (Todd, Kuhlthau, & Heinstrom, 2005). To gather evidence of library management, including collection development, the environment, and services, teacher librarians can source benchmarks from peer institutions, questionnaires or surveys to evaluate performance, set new goals or standards and implement strategies. Benchmarks from peer institutions can be sourced through network meetings and through the Softlink survey.

As a school library that runs a college-wide academic reading and writing program, we utilise data to assess the extent to which the programs effectively improve student learning. Reading comprehension tests help the teacher librarians and teachers determine the effect of the strategies on student abilities. Teacher librarians should work with heads of department and classroom teachers to analyse and digest the data in meaningful ways. Collaboration is central to the perception of the data analysis process. Teachers do not want to fall victim to judgement due to the results within their class. While this is important to note, it is also important to hold honest and open conversations about opportunities the data may present. Viewing the results through an opportunities lens ensures all stakeholders feel safe and valued and student learning is central.

This year, I have been delving deeper into the world of data and evidence to assess the impact the Study Skills program has for our boarding students. The program is designed to assist boarding students with; organisation, prioritisation, study skills, assessment skills, and research skills, while growth mindset underpins the sessions. A teacher librarian (myself on Tuesday and Wednesday nights and our Head of Library on Monday nights) facilitate a half hour targeted session with the students in the senior library – one cohort per night on a weekly rotation. These sessions are timely and relevant to the assessment and class work to ensure the value is clear. After the half hour session, the students undertake their independent study for the remaining hour and a half, while the teacher librarian circulates and assist students in smaller groups and one-on-one. I am pleased to share that since the inception of the program last year, the boarders’ results are trending up – often at a greater rate than the day students. While many factors influence the boarders’ results (strategies from classroom teachers, tutoring, support from boarding supervisors and parents for example), the results are also indicative of the renewed impetus for study and a changing culture that has developed from the program. The program has been a feat of collaboration and has seen staff members from across the college come together for this common cause. To gather evidence, I was able to use data from both Learning Analytics and TASS to compare day and boarding groups, and boarding groups over time. This also provides me with opportunities to compare external high-stakes results, such as NAPLAN results, with curriculum results. This evidence was used to not only assess the effectiveness of the program but also to open conversations with staff and students about learning outcomes. From this, I created a report to document the findings and present to teaching staff and leadership team (Figure 3). I have had incredibly valuable conversations with students concerning their progress and strategies going forward. One-on-one, I talked to students about their GPAs, compared these against their report cards, then again against their individual assessment tasks to identify strengths and areas for improvement. The additional ownership students took of their results and the empowerment felt was palpable. The evidence is used to evaluate and reflect on the programs, to plan targeted sessions, to empower students, and to advocate for the work done by the teacher librarians.

Ultimately, learning must be at the centre of the analysis, discussion and subsequent initiatives or action. Evidence must be gathered on a local level to determine the effectiveness of library programs and through other means, such as empirical research, to ensure best practice. Evidence must be made explicit and concerted efforts must be made to “measure the relationship between inputs, outputs, actions and student outcomes” (Hughes, Bozorgian, & Allan, 2014, p. 15). These practices can help to ensure the longevity of the school library and assert the library and staff as invaluable to the school community.

References

Gillespie, A. (2013). Untangling the evidence: Teacher librarians and evidence based practice [Thesis]. Retrieved from https://eprints.qut.edu.au/61742/2/Ann_Gillespie_Thesis.pdf

Hughes, H., Bozorgian, H. & Allan, C. (2014). School libraries, teacher-librarians and student outcomes: Presenting and using the evidence. School Libraries Worldwide, 20(1), 29-50. doi: 10.14265.20.1.004

Oddone, K. (2017). Action research for teacher librarians [Infographic]. Retrieved from https://my.visme.co/projects/jwvj7ogk-action-research-for-teacher-librarians#s1

Renshaw, P., Baroutsis, A., van Kraayenoord, C., Goos, M., and Dole, S. (2013). Teachers using classroom data well: Identifying key features of effective practices. Final report. Retrieved from https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/default-document-library/teachers-using-classroom-data-well.pdf

Robins, J. (2015). Action research empowers school librarians. School library research, 18, 1-38. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.csu.edu.au

Todd, R. J. (2015). Evidence-based practice and school libraries: Interconnections of evidence, advocacy, and actions. Knowledge Quest, 43(3), 8-15. Retrieved from https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.csu.edu.au

Todd, R., Kuhlthau, C. & Heinström, J. (2005). School library impact measure SLIM: A toolkit and handbook for tracking and assessing student learning outcomes of guided inquiry through the school library. Retrieved from https://cissl.rutgers.edu/sites/default/files/inline-files/slimtoolkit.pdf