Evaluation of collections assesses the extent to which library collections meet the goals of the library and the needs of the community it serves. There are various methods of evaluation that can be employed in school libraries. ALA identifies two categories of collection evaluation; collection-centered measures, and use-centered measures (Evans & Saponaro, 2014). A balanced way of evaluating the collection is to employ several of these methods and to ensure objective data is gathered in the mix. Grigg (2012) proposes methods of evaluating collections that are suitable for both print and digital resources. The methods and their usefulness in school library collection evaluation is outlined below:

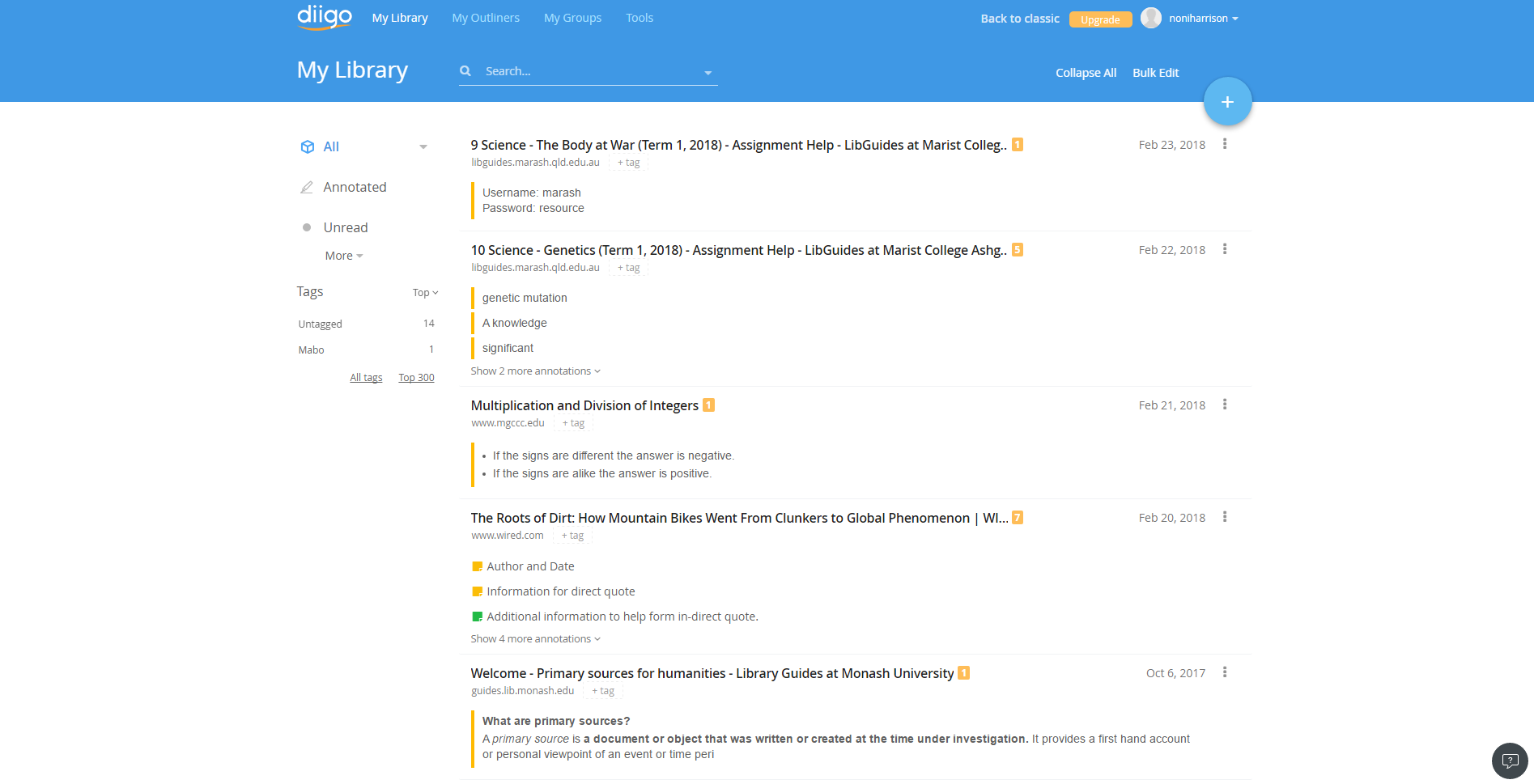

Usage data: assessing circulation statistics.

- Useful in determining the popularity of resources and the subject areas that are most borrowed and types of books used. This can be helpful in assessing how the collection meets learning needs and reading needs.

Overlap analysis: assessing duplications within journal collections.

- Useful in minimising wasted dollars through unnecessary duplicate resources.

Survey instruments: quantitative method of collecting user feedback.

- Useful in determining the users’ impression of the library and collection and the usefulness of the collection in meeting specific needs. This value of this method is increased when used in conjunction with another method of evaluation.

Benchmarking: comparing the collections of different libraries.

- Useful in identifying potential gaps and strengths in comparison to other school libraries. This could be done during network meetings to provide suggestions and recommendations and collaborate with others in developing quality collections to meet the needs of the clientele.

Focus groups: qualitative method of collecting user feedback.

- Useful in determining the strengths and weaknesses of a collection from the perspective of the library users. This method should be used in conjunction with other methods of evaluation, as the results may be bias or may only apply to a niche market.

Balanced scorecard methods: matching criteria or outcomes against circulation statistics.

- Useful in assessing circulation statistics against particular goals; however, there is difficulty in developing realistic or accurate criteria and this does not account for the quality of the resource it only counts the use.

What are the practicalities of undertaking a collection evaluation within a school in terms of time, staffing, and priorities, as well as appropriateness of methodology?

Collection evaluation can be an expensive process in terms of staff time (Arizona State Library, n.d.); however, it is important to make time to ensure this process is undertaken. There are opportunities throughout the school year to allocate time to this process; for example, during staff days at the beginning of end of term, and during weeks when classes are limited (e.g. weeks 7-8) and TL time becomes available for other library management duties. This should be a priority when receiving assessment task sheets or unit outlines from teachers and when organising assignment help lessons. Methods must relate to all aspects of a school library; including, assessment and curriculum support, reading for pleasure, resources for teaching and other staff, resources to support the wider community. Additionally, the methodologies used should take advantage of the resources available to ensure the process is efficient; for example, using the OPAC to gather data and generate reports.

How does the need for, and possible benefits of an evaluation of the collection outweigh the difficulties of undertaking such an evaluation?

- Despite the difficulties in undertaking collection evaluation it is vital in determining how and to what extent school libraries are meeting users’ needs and in cementing the library in the school context as a valuable commodity. As highlighted by Hernon, Dugan, and Matthews (2014), evaluation activities provide evidence of accountability and the opportunity to review and modify practices in a clear and formal manner. It also provides justification for changes in selection priorities and supports weeding or deselection decisions (Pattee, 2013). Collection evaluation is paramount in ensuring the collection’s usefulness and relevance to the school community.

Is it better to use a simple process with limited but useful outcomes, or to use the most appropriate methodology in terms of outcomes?

- The answer to this question may change depending on the aspect of the collection needing to be evaluated – general or specific emphasis collections. Overall, the most appropriate methodology in terms of outcomes is the ideal method a TL would use when evaluating the collection; however, constraints including time and staffing may interfere with this. When evaluating the collection to meet curriculum needs, it is important to use the most appropriate methodology, as it is the role of the school library to meet these needs and assist teachers and students in understanding and navigating the new curriculum. If evaluation processes occur more regularly, they will become quicker and easier, as the process is streamlined and more regularly updated. Furthermore, the collection will more accurately reflect the library’s mission and changing needs of the community. Hernon, Dugan and Matthews (2014) even suggest that evaluation activities should become daily activities within libraries to review and improve services with the aim of meeting stated goals and objectives. The National Library of New Zealand recommends weeding monthly or quarterly, which could also be a useful time to undertake other evaluation processes (2012).

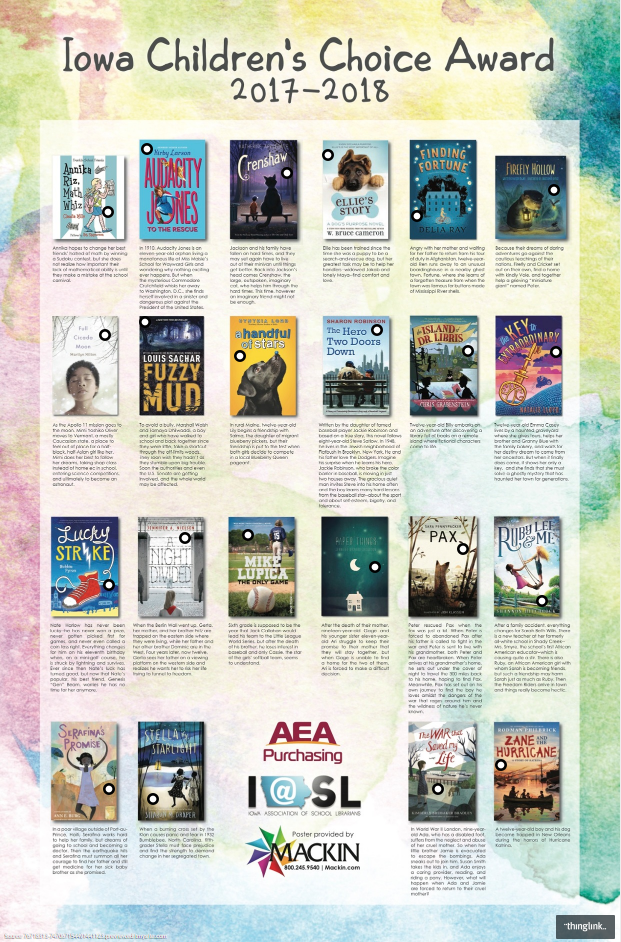

What are the current priority areas for evaluation in your school library collection?

- Current priority areas for evaluation in my school library collection include, evaluation of the non-fiction collection in meeting curriculum needs of senior students studying the Arab Israeli Conflict, and Year 9 and 10 Science students undertaking new inquiry tasks requiring them to break down science claims and develop very specific research questions that require resources to support the question and their reading levels.

References

Arizona State Library. (n.d.). Collection assessment and mapping. Retrieved from https://www.azlibrary.gov/libdev/continuing-education/cdt/collection-assessment-mapping

Evans, G. E., & Saponaro, M. Z. (2014). Library and information science text: Collection management basics. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.csu.edu.au

Griggs, K. (2012). Assessment and evaluation of e-book collections. In R. Kaplan (Ed.), Building and managing e-book collections: A how-to-do-it manual for librarians (pp. 127-137). Retrieved from https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.csu.edu.au

Hernon, P., Dugan, R. E., & Matthews, J. R. (2014). Getting started with evaluation. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.csu.edu.au

National Library of New Zealand. (2012). Weeding your school library collection. Retrieved from https://natlib.govt.nz/schools/school-libraries/collections-and-resources/weeding-your-school-library-collection

Pattee, A. S. (2013). Developing library collections for today’s young adults. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.csu.edu.au

[Reflection: Module 5.1]