Reading Sara Mosle’s post “What should children read?” on Opinator (New York Times, 2012) raised some conflicting thoughts and feelings for me. I decided a blog post would be a good way to excise them.

Mosle’s post is in response to the introduction (in 2014) of the Common Core curriculum in the United States; she says that “Per the guidelines, 70 percent of the 12th grade curriculum will consist of nonfiction titles” which has resulted in a ‘skirmish’ between advocates on both sides.

She quotes David Coleman, president of the College Board and one of the writers of the new curriculum, as saying that employers don’t need or want “‘a compelling account of your childhood.’” I found this reasoning somewhat bizarre. Does Coleman not understand the purpose of fiction? Stories help us make sense of the world and understand human nature, what it means to be human. Through stories, we get to experience other ways of being and are exposed to different perspectives. I agree with Diane Ravitch who Mosle quotes as saying, “I can’t imagine a well-developed mind that has not read novels, poems and short stories.”

Yet Mosle also makes an excellent case for good quality, literary nonfiction. Such texts also allow us to experience other ways of living and other perspectives, but I don’t see that they should replace fiction. In the pre-tertiary English course I teach, in the Genre Studies module, teachers can choose to teach “Life Writing”. The texts in the prescribed list are all worthy and interesting, but the problem teachers have encountered is that, as a genre, it’s ill-defined. What are the common text conventions? Students struggle to even articulate purpose.

That said, literary non-fiction is wonderful. It seems to be a relatively recent ‘genre’, an extension of memoir which used to be called autobiography – but memoirs are so much more aren’t they!

I’ve got a bit of a collection myself. Some of these titles I’ve read already, some I haven’t got to yet. Some are in the memoir, life writing genre, others weave personal experiences into the issues and topics they’re writing about, to humanise them. Here are just a few, on a wide range of topics:

I bought a copy of Yumiko Kadota’s new book Emotional Female (2021) just the other day after reading about it on author Bri Lee’s Instagram page.

I bought a copy of Yumiko Kadota’s new book Emotional Female (2021) just the other day after reading about it on author Bri Lee’s Instagram page.

It is about “a brilliant young surgeon’s journey through ambition and dedication to exploitation and burnout” within the Australian public hospital system and is something of an expose. Can’t wait to read it, though I know it will enrage me as well!

Another book that really did enrage me – for the right reasons – is Anna Krien’s Into the Woods: The Battle for Tasmania’s Forests (2010) which was an incredible expose into the forestry practices here.

Another book that really did enrage me – for the right reasons – is Anna Krien’s Into the Woods: The Battle for Tasmania’s Forests (2010) which was an incredible expose into the forestry practices here.

“She speaks to ferals and premiers, sawmillers and whistle-blowers. She investigates personalities and convictions, methods and motives. This is a book about a company that wanted its way and the resistance that eventually forced it to change.” (blurb)

Sadly, there hasn’t been as much change as that description implies. Mostly, Forestry Tasmania changed its name to Sustainable Timbers Tasmania, a complete misnomer!

Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu is one of those incredible life-changing books that all Australians should read.

Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu is one of those incredible life-changing books that all Australians should read.

He uses primary sources from colonisers and settlers to prove that Indigenous Australians (First Nations peoples) did in fact farm the land, and had complex and clever systems for doing so.

He also explains why this isn’t general knowledge, which again is tied up in privileging white history over black.

French writer Philippe Squarzoni’s 2012 book Climate Changed: A personal journey through the science is in graphic novel format, so while it’s long and heavy it’s very accessible (and the only non-Australian text on this short list). Part diary, part documentary, it weaves in scientific research and interviews with experts to explain the complicated concept of global warming.

French writer Philippe Squarzoni’s 2012 book Climate Changed: A personal journey through the science is in graphic novel format, so while it’s long and heavy it’s very accessible (and the only non-Australian text on this short list). Part diary, part documentary, it weaves in scientific research and interviews with experts to explain the complicated concept of global warming.

He includes charts and graphs – in graphic novel style – and the illustrations make reading this a similar experience to watching a documentary. The black-and-white illustrations do lend it a doomsday feel though!

The Hate Race, Maxine Beneba Clarke’s 2016 memoir of growing up black in white suburban Australia, is one I haven’t yet read. The Weekend Australia said it is “an unflinching account of being a black child, a black woman, a black mother, in modern Australia. Everyone should read it.”

The Hate Race, Maxine Beneba Clarke’s 2016 memoir of growing up black in white suburban Australia, is one I haven’t yet read. The Weekend Australia said it is “an unflinching account of being a black child, a black woman, a black mother, in modern Australia. Everyone should read it.”

As a white Australian, I must listen to other voices to understand their experiences more fully, so I can help bring about change.

I read Julia Baird’s book Phosphorescence: On awe, wonder and things that sustain you when the world goes dark fairy recently, and it’s absolutely gorgeous.

I read Julia Baird’s book Phosphorescence: On awe, wonder and things that sustain you when the world goes dark fairy recently, and it’s absolutely gorgeous.

I don’t know how many teenagers it would appeal to, to be honest, but I also hate making that kind of decision for them.

Baird blends personal life writing with scientific research on a range of topics, including ‘forest bathing’ and cuttlefish, and tackles things such as how to be present instead of anxious. The writing quality/style and research and interviews rescue it from being a self-help book. (Yes I did buy it because the cover is so beautiful, but it became one of my favourite reads.)

Jackie French’s 2013 history book Let the Land Speak provides a fascinating re-examination of the colonisation of Australia from an environment perspective, and an Indigenous one (French, while white, was informally adopted by an Aboriginal tribe when she was a homeless teenager).

Jackie French’s 2013 history book Let the Land Speak provides a fascinating re-examination of the colonisation of Australia from an environment perspective, and an Indigenous one (French, while white, was informally adopted by an Aboriginal tribe when she was a homeless teenager).

Still very topical, she challenges several assumptions about the history of Australia, and practises like fuel reduction burns. I’ve used excerpts from this in the past when teaching Kate Grenville’s The Secret River in English Literature. This book is also available in a series of books for children called Fair Dinkum Histories, with funny cartoon-style illustrations by Peter Sheehan.

Witches: What women do together came out in 2019 as part of Sam George Allen’s PhD thesis and it really deserves greater attention than it got.

Witches: What women do together came out in 2019 as part of Sam George Allen’s PhD thesis and it really deserves greater attention than it got.

Each chapter focuses on a different grouping of women with a strong Australian angle, on a wide range of topics. From make-up to nuns, sportswomen to fangirls, she helped me shift my mind set and unearthed some prejudices I didn’t want to acknowledge.

______________________________

Returning to the subject of tension between fiction and non-fiction, I love that my school doesn’t have this. We see value in both, and advocate for both. While I’m not teaching any non-fiction titles, I use them as sources of research for myself and my students: good quality non-fiction is invaluable.

I would like to see space made in our courses for non-fiction, though. I would love to teach books like The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks; to date, the only non-fiction book I have taught is The Tall Man by Chloe Hooper (another excellent read).

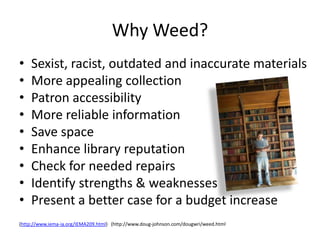

We’ve all observed the problems with how we skim online articles, rather than reading in-depth, and issues with attention span, focus and commitment. Our knowledge becomes as superficial as the clickbait we read. But the other point, not mentioned in the article, is how more information-based non-fiction (not so much memoir) are excellent tools for teaching students skills around organising content and how to find it. I’ve had many students who don’t know how to use an Index, are are defeated by a contents page (and way too many who claim not to understand what you mean by ‘alphabetical order’!). While non-fiction titles are vital to a healthy library and a healthy curriculum, surely a balance is the better idea? Why 70% across all subjects? From one extreme to another.

Recent Comments

shannon.badcock

"Yes I wondered/worried about that. I find it hard to separate it from ..."

ederouet

"What a great looking blog! I love your widgets and use of categories ..."