Such an interesting topic! Having been through an English degree, the word ‘literature’ is stuck in my brain as meaning something along the lines of canonical, and ‘high brow’ – I don’t agree with it but the word has been used in such a way throughout the 20th century, and that’s the meaning I grew up with. (In short: elitism, often guarded by old white men.)

So some of the definitions of children’s literature rub my feathers the wrong way – especially the definition that includes non-fiction (Ross 2014).

The definitions that resonate with me are ones like Kathy Short’s (2018), who says that literature illuminates “what it means to be human and to make accessible the fundamental experiences of life” (p.291). I can see that a lot of non-fiction can do this as well, which brings me to the sticky part: quality.

Barone (2010) explores the definition of children’s literature as being of ‘good quality’ if it meets “critical analysis” or “readers’ appreciation” (p.7), stressing that this is subjective.

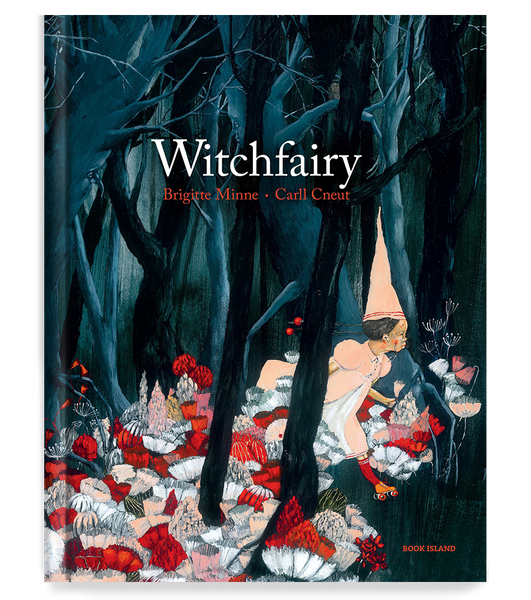

Witchfairy by Brigitte Minne & Carll Cneut

Too often, it is assumed that children’s literature must be ‘simple’ and ‘easy’ because it is often defined by age range – birth to the end of adolescence (variously 16 or 18, depending on the source). But they are far from simplistic – they are often quite complex and deal with sophisticated subject matter. It is the form that creates the illusion of simplicity. Really, ‘simplicity’ is more accurately ‘accessibility’. Like adult literature, children’s literature helps readers access a complex world, shape it, understand it and thus ‘control’ it (Saxby, 1985 in McGregor, n.d.) – i.e. control how it fills their brain and helps them navigate anxiety.

Accidental Heroes by Lian Tanner

The way that we sort literature – into adult and children’s – is by form, which publishers control. Children’s literature is going to look different – larger font, more white space, often illustrations, brightly coloured covers. The style of writing is different from adult fiction – some adult novels seem to be simply, sparsely written yet the ideas are denser, and require broader, deeper cultural knowledge and understanding of society etc.

Some works of literature sit uneasily across manufactured, age-based divides, reminding us that, originally, there was no ‘children’s literature’; children read adult books (Barome, 2010, p.8).

Honeybee by Craig Silvey

Books such as Jasper Jones and The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time are novels that I understood to be adult fiction, but which others see as children’s literature because the protagonist is a child. Yet the protagonist of My Absolute Darling is also a child but due to its graphic content I would not feel comfortable recommending it to a child (I don’t say this because I want to censor it, but because it’s most definitely an adult book about a child). So the age of the protagonist cannot be used as a sole definer of what makes a children’s book.

Having read through all these definitions and more, I can see why there’s no one clear understanding. Ultimately, children’s literature serves the same purpose as adult literature: to help us see the world in new ways, create a safe space for us to feel new feelings, and challenge us to think again. The ‘why’ seems to be similar. It’s the way this is done – the ‘how’ – that is a bit different.

Leave a Reply