As I near the end of ETL503 Resourcing the Collection, I feel the need to consolidate my understanding somewhere – and what better place than my blog?

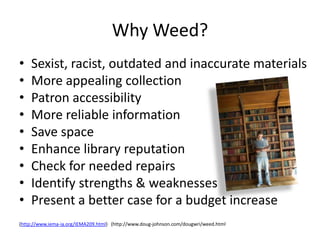

I have written a blog post on the TL’s role in selecting resources; reflected on Sara Mosle’s post “What should children read?” and the debate about non-fiction vs fiction; mused about the limitations of a digital collection; reviewed online curating tools; discussed budget proposals and who should control the library budget; compiled information on various methods of evaluating the collections and the benefits and challenges of weeding; and considered self-censorship in light of student mental health and wellbeing (because that’s where my thoughts happened to take me at that time).

In all of that, though, I find on reflection that I’ve skirted around some of the key points. Namely, why do we need a Collection Development Policy and how can it ‘future proof’ the collection?

Khan and Bhatti (2021) quote several sources in explaining what ‘collection development’ means, which can be synthesised (and simplified) as the plan for acquiring, maintaining and disposing of items in the library collection. A key distinction here is that it is a plan, a process, an outline that provides structure, and that it must be in response to the users’ needs. It is not the ‘how’ so much as the ‘what’ – the how belongs in a Procedures manual for library staff to follow. A Collection Development Policy is a guide, a framework – as a ‘policy’ it supports the decision-making processes of the library staff, both providing some direction and some support.

What’s telling is why this is needed in the first place. As Wade (2005, p. 12) says, “today’s librarian is a new breed that no longer keeps saying ‘quiet’ and is concerned with more than just how to catalogue items under the Dewey Decimal system.” With the increase in complexity of the information literacy sciences comes an increase in responsibility. Teacher Librarians (TL) must contend with various forms of technology – both using it, managing it and supervising it – as well as new and varied sources of information – in terms of quality and access.

Compounding this is the reduction of funding of school libraries, TL positions on staff – and the dearth of TLs overall (in Tasmania, there are only a couple left!). So the TL must do more, often with less. Less time, less staff, less funding, less collaboration with teachers – because they too are time-poor, over-stretched and, when schools don’t even have a TL, there’s no one for them to collaborate. Many new teachers wouldn’t even know what a TL does because they’ve never worked with one. What a sad thought!

So, what can a TL do? Draft a solid Collection Development Policy to make it clear that they’re not just buying random books and that there’s more involved than just cataloguing, shelving and checking them out. And then shelving again.

A Collection Development policy is part of a larger process that begins with analysing the needs of the school’s users, and extends to budget, selection, acquisition, collection maintenance, evaluation and de-selection (Khan & Bhatti). Collection development, overall, includes planning, consultation, goal-setting, decision-making, promotion and sharing (Khan & Bhatti).

‘Planning’ is another way of saying ‘analysing users’ needs’, because that is always going to be the start and end point: the purpose and the outcome. When it comes to the students, so many things need to be considered, including the curriculum; the school context (e.g. socio-economic status; setting – remote/rural, inner urban; religious affiliation etc.); the diverse profiles of the student body (language, citizenship status, age, neurodiversity, interests etc.); the school’s goals and strategic aims; access to technology; and, encompassing it all, the library budget.

Planning must also exist within the purpose of the library. Fleishhacker (2017, p.31) says that TLs should provide resources that motivate students to read. The first standard for the teaching profession is “Know students and how they learn” (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership, 2017); Mathur (2022) says that it is “imperative” that TLs support the variety of teaching and learning styles that exist in a school, and quotes Carrigan in Johnson (2009) in saying that “‘choice’ is the essence of collection development”.

It sounds simple but gets tricky – and this is where people don’t really understand just what a TL does. In providing ‘choice’, in selecting resources that engage, inform, present multiple perspectives and points of view, that represent diversity, educate and entertain, the TL must be aware of their own biases (the better to avoid self-censorship) and use a methodical approach to avoid challenges.

A “tightly written collection development policy that spells out how you approach deciding what goes in the collection (including how gift items are handled) and […] how to handle challenges to materials” will provide support for the TL (Shores, 2018, p. 175-6).

References

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership. Australian professional standards for teachers. (2017). https://www.aitsl.edu.au/standards

Fleishhacker, J. (2017). Collection development. Knowledge Quest, 45(4), 24–31.

Khan, G., & Bhatti, R. (2021). An argument on collection development and collection management. Library Philosophy and Practice, 1-7. https://primo.csu.edu.au/permalink/61CSU_INST/15aovd3/cdi_scopus_primary_2012013622

Mathur, P. (2022). Curate, advocate, collaborate: Updating a school library collection to promote sustainability and counter eco-anxiety. Scan, 41(2). https://education.nsw.gov.au/teaching-and-learning/professional-learning/scan/past-issues/vol-41-2022/issue-2-2022

Shores, W. (2018). Collection development in an era of “fake news”. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 57(3). DOI: 10.5860/rusq.57.3.6601

Wade, C. (2005). The school library: phoenix or dodo bird? Educational Horizons, 8(5), 12-14. https://search.informit.org/doi/epdf/10.3316/aeipt.144858

Recent Comments

shannon.badcock

"Yes I wondered/worried about that. I find it hard to separate it from ..."

ederouet

"What a great looking blog! I love your widgets and use of categories ..."