[Module 5: Evaluating Collections]

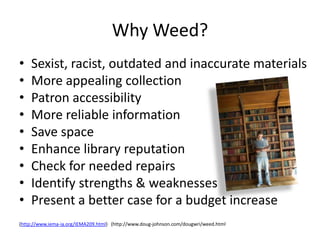

Why weed? The benefits:

A key purpose of the library collection is to provide relevant and useful information and ideas in accessible formats to the staff and students of the school.

Yet, information becomes out-of-date, resources become old and unappealing, interests change and so do the available formats. In order to keep the school library collection engaging, current (as relevant), reflective of the community and curriculum (debmille, 2011), and in good condition, it is important to undergo the process of weeding as regularly as time and staffing allows.

More specifically, weeding is beneficial for the following reasons:

(debmille, 2011, slide 6)

CREW lists the six benefits of weeding as:

- space saving

- time saving

- improve the collection’s appeal

- enhance the library’s reputation

- keep up with collection needs

- constant feedback on the strengths and weaknesses of the collection

(Larson, 2012, pp. 15-16)

In Rebecca Vnuk’s book The Weeding Handbook (2015), she outlines several benefits to weed the library collection:

- To free up shelf space (p. 1)

- To increase your knowledge of what’s in the collection (p. 1)

- To purge outdated materials (p. 2)

Jennifer LaGarde’s blog post “Keeping your library collection smelling FRESH” (2013) specifies some excellent reasons for weeding the school library collection:

- Old resources can include misinformation

- The quality of the text and visual can be poor

- Older texts can be so unappealing, students don’t want to try them

- The content may be so out-of-date that it includes offensive stereotypes, outdated language and concepts – good as a teaching resource, but not reflective of the diversity of the cohort or inclusive or equitable

- A dated, tatty collection makes the whole library seem dated and tatty, which is off-putting

Similarly, her “F.R.E.S.H.” poster – a guide for what to weed – can be interpreted as reasons to do so.

- The collection should foster a love of reading

- It should reflect the school community’s diverse population – each student should be represented

- It should reflect an equitable world view, a variety of perspectives and “encourage global connections” (not be insular, inward-thinking, or foster an attitude of superiority)

- It should support the courses offered at the school

- The resources in the collection should be of high quality.

Weeding the collection ensures that it meets these standards. To do it in such a way as to avoid complaints or challenges, the New Zealand National Library (n.d.) stresses the importance of selecting (and sticking to) criteria for weeding. These criteria would be context-specific, and can be adapted from the benefits, above.

For instance, regarding the quality of the text, a criterion could be “the item is in poor condition”. Your library’s policy could expand on each criterion to provide specifics or examples – in this case, “the item is tatty, has poor/weak binding, is missing pages, has food or drink stains, is badly creased or dog-eared, is beginning to smell (e.g. from a breakdown of the resin/glue used in the binding).”

The challenges:

Vnuk (2015) says that while for many, ‘purging’ or weeding the library collection of unwanted, out-of-date, and worn-out books seems to go against the role of the librarian, it in fact lies at the heart of the TL’s role, as expressed by “S. R. Ranganathan’s Five Laws of Library Science: Save the time of the reader and The library is a growing organism.” (p. 2) Still, it can be hard to throw out books when so many librarians are drawn to the role partly from a love and/or appreciation of them. There are many ‘what ifs’, most especially:

What if I weed it and then someone needs it?

Another challenge might be the library’s budget: does the library have the funds to replace what is weeded?

Thirdly, there’s the challenge of deciding who is responsible for the job (Vnuk, 2015, p. 3). This needs to be spelled out in the collection development policy, along with the weeding criteria, timeframe/frequency, and what do to with the weeded books.

Which brings us to the fourth challenge: what to do with weeded books. The National Library of New Zealand (2014) has some useful suggestions in their video. Discarding books would need to be decided on a case-by-case basis. You can discuss literary books with English teachers to get their input, and any that they feel may appear on a future text list can be re-categorised and placed in the Stacks.

Duplicates could find a home in a classroom, as can books that haven’t been checked out in over 10 years. Many can be donated to the school fair’s book sale table, or similar. But those that are grungy and falling apart will need to simply be thrown out (unless the Art teachers want some for a project? Always good to ask around!).

References

debmille. (2011). Weeding not just for gardens [Slideshare]. http://www.slideshare.net/debmille/weeding-not-just-for-gardens

Larson, J. (2012). CREW: a weeding manual for modern libraries, Austin, TX: Texas State Library and Archives Commission. https://www.tsl.texas.gov/sites/default/files/public/tslac/ld/ld/pubs/crew/crewmethod12.pdf

LaGarde, J. (2013, October 1). Keeping your library collection smelling F.R.E.S.H! [blog post]. The adventures of Library Girl. https://www.librarygirl.net/post/keeping-your-library-collection-smelling-f-r-e-s-h

National Library of New Zealand, Services to Schools. (n.d.) Weeding your school library collection. https://natlib.govt.nz/schools/school-libraries/collections-and-resources/weeding-your-school-library-collection

NationalLibraryNZ. (2014, March 30). Weeding your School Library [Video]. YouTube https://youtu.be/ogUdxIfItqg

Vnuk, R. (2015). The Weeding Handbook: A shelf-by-shelf guide. Chicago, ALA Editions. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/CSUAU/detail.action?pq-origsite=primo&docID=4531556

Leave a Reply