Resource 3 – The Land of the Magic Flute

Summary:

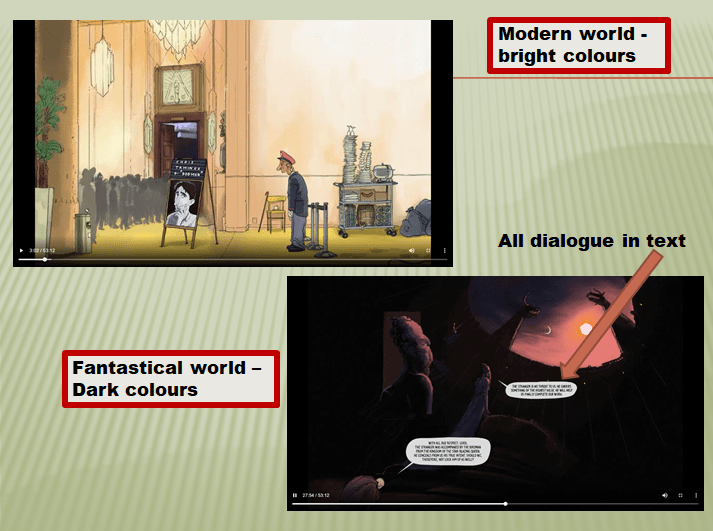

The Land of the Magic Flute is a convergence of music, narrative and digital media and can be described as a modern opera. Based upon a famous Mozart & Schikaneder Singspiel, Die ZauberFlote (1791) , this graphic novel (GN) adaptation is a quest for enlightenment, knowledge, justice and truth that is conveyed through haunting imagery, text, sound and Mozart’s arias. The colour and images are very evocative of two main settings, with the modern world in bright colours, and the fantastical world in sombre shades with harsh angles. This resource would appeal to fans of classical music, graphic novels and multimodal literature.

The Land of the Magic Flute is a convergence of music, narrative and digital media and can be described as a modern opera. Based upon a famous Mozart & Schikaneder Singspiel, Die ZauberFlote (1791) , this graphic novel (GN) adaptation is a quest for enlightenment, knowledge, justice and truth that is conveyed through haunting imagery, text, sound and Mozart’s arias. The colour and images are very evocative of two main settings, with the modern world in bright colours, and the fantastical world in sombre shades with harsh angles. This resource would appeal to fans of classical music, graphic novels and multimodal literature.

Curriculum Links:

- Year 7 English – ACHHS214

- Year 8 English – ACHHS157

- Year 9 English – ACELT1637/ ACELY1739 / ACHHS175

- Year 7 & 8 Music – ACAMUR097

- Year 9 & 10 Music – ACAMUR104

Learning, Literacy and Language:

Graphic novels (GN) offer great opportunities for promoting language, literacy and learning, but are often underestimated because of their non traditional format (Laycock, 2019; Gonzales, 2016). The Land of the Magic Flute uses clever combinations of prose, poetry, film, imagery and music to convey the storyline and this makes it a valuable resource for content delivery, as well as improving multimodal and critical cultural literacies (Laycock, 2019). GN are predominantly used within language arts courses, but can also be utilised effectively across other content areas to support literary learning. For example Maus (1991), Auschwitz (2004) and Bag of Marbles (1973) are frequently used in studying the Holocaust as the visual nature of the GN allow readers to relate to the sensitive issues within the text without being overwhelmed (Gonzales, 2016).

Graphic novels (GN) offer great opportunities for promoting language, literacy and learning, but are often underestimated because of their non traditional format (Laycock, 2019; Gonzales, 2016). The Land of the Magic Flute uses clever combinations of prose, poetry, film, imagery and music to convey the storyline and this makes it a valuable resource for content delivery, as well as improving multimodal and critical cultural literacies (Laycock, 2019). GN are predominantly used within language arts courses, but can also be utilised effectively across other content areas to support literary learning. For example Maus (1991), Auschwitz (2004) and Bag of Marbles (1973) are frequently used in studying the Holocaust as the visual nature of the GN allow readers to relate to the sensitive issues within the text without being overwhelmed (Gonzales, 2016).

Digital graphic novels (DGN) promote emerging literacies and critical thinking, because the narrative structure and complex storyline provides the reader with cultural history and context (Karp, 2011; Maniace, 2014; Brenner, 2015). Readers are able to identify emotions from the variance in facial expressions, body language and physical metaphors present. The sequential imagery, linearity of narrative and visual permanence facilitate text comprehension for reluctant readers, visual learners, low literacy and EALD students (Gonzales, 2016; Brenner, 2015; Botzakis, 2018; Karp, 2011). The features such as embedded music and computer graphics, were used successfully to enhance the storyline (Kirtz, 2014).

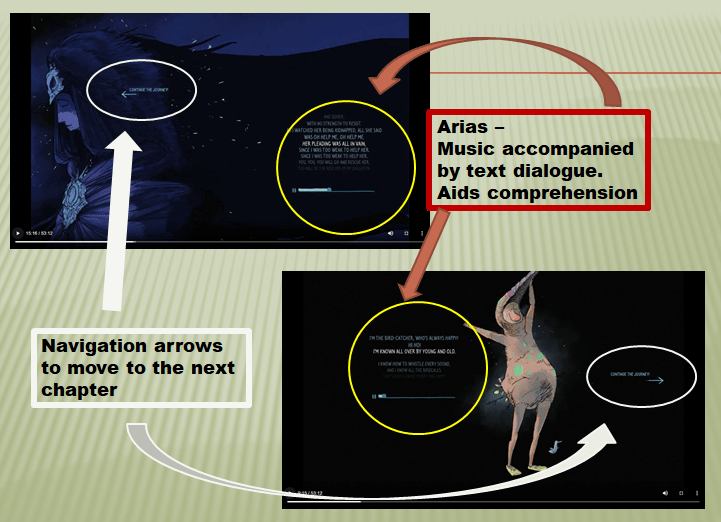

The embedding of the seven Mozart arias during pivotal points in the narrative gives the reader time to contemplate the storyline and the value of that modality at that point in the story. The arias are supported by subtitles and emphasise the tension in the story, allow the reader time to analyse the words in conjunction with the graphics and this combined effect provides context for increased comprehension and independent reading (Botzakis, 2018; Leu, 2005). The inclusion of fantastical creatures meets the needs of adolescents who seek fantasy stories as a method in which to understand and investigate the difference between good and evil in humanity (Kole, 2011).

The embedding of the seven Mozart arias during pivotal points in the narrative gives the reader time to contemplate the storyline and the value of that modality at that point in the story. The arias are supported by subtitles and emphasise the tension in the story, allow the reader time to analyse the words in conjunction with the graphics and this combined effect provides context for increased comprehension and independent reading (Botzakis, 2018; Leu, 2005). The inclusion of fantastical creatures meets the needs of adolescents who seek fantasy stories as a method in which to understand and investigate the difference between good and evil in humanity (Kole, 2011).

DGN have great capacity for innovative teaching, but educators are disinclined to utilise GN because of the assumed lack of literary qualities and that they require the same explicit instruction and scaffolding as traditional texts for comprehension and literacy development (Phelps, 2011; Botzakis, 2018; Hallman & Schieble, 2012). The reality is that that explicit instruction and the effective teaching of multimodal literacies utilising DGN can lead to a transference of ability to other texts and disciplines (Hallman & Schieble, 2012).

Trends:

Digital GN is the convergence of two major literary trends: sophisticated graphic narratives and digital literature (Moorefield-Land & Gavigan, 2012; Walsh, 2013). The recent plethora of DGN is due to its lowered publication costs and this allows emerging artists and authors increased opportunities for self publication (Moorefield-Lang & Gavigan, 2012). Whilst GN collectors prefer print editions, avid readers tend to prefer digital versions as they are often cheaper and can be purchased on the release date (Wilson, 2019).

Technology:

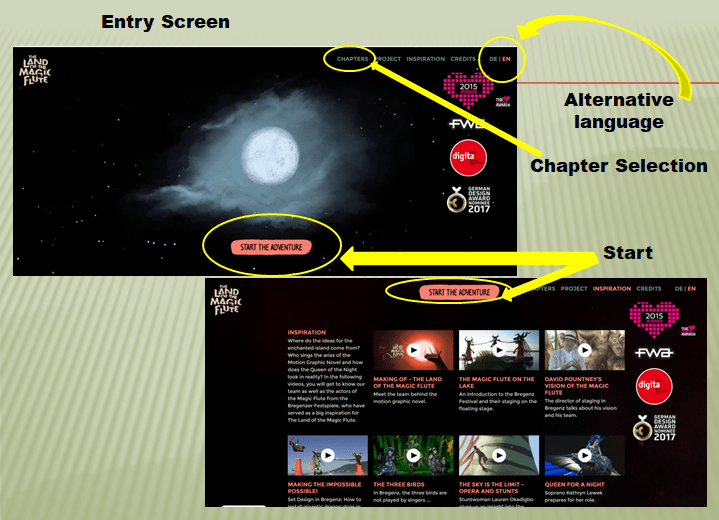

The Land of the Magic Flute is accessible on all devices with internet access and Flash or Javascript installations, but the digitisation effect is more pronounced on tablets (Wilson, 2019). Authentic learning requires students to be in their third place, and integrating GN and DGN into the curriculum narrows the strong dichotomy between student choice and curriculum canon (Grazotis, 2017; Phelps, 2011; Laycock, 2019) .

Resource integration:

GN are traditionally classified within Dewey at 741.5 but most school libraries merge all titles to a single location and whilst DGN cannot be physically stored in a particular location, it can be catalogued and linked into the library management system (LMS) (Kan, 2020). The Land of the Magic Flute can be integrated into the LMS, LibQuests and class intranet pages as well as accessible from most devices, which makes it an excellent teaching tool. Like other interactive websites, there is no guarantee of longevity and as the resource requires internet access to work. It would be recommended that this DGN is used for classroom practice to limit the digital demand on rural, remote and low income households (DIIS, 2016).

Recommendation:

The Land of the Magic Flute successfully meets the needs of the curriculum, as well as addresses the developmental, literacy and critical thinking needs of the modern teenager. It would make a valuable addition to a school library collection.

References:

Brenner, R. (2015). A guide to using graphic novels with children and teens. Graphix. Scholastic Teachers. Scholastic. Retrieved from https://www.scholastic.com/teachers/lesson-plans/teaching-content/guide-using-graphic-novels-children-and-teens/

Graphic Novels in Education [Blog]. American Libraries. Retrieved from https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/2011/08/01/the-case-for-graphic-novels-in-education/

Graphix. (2018). A guide to using graphic novels with children and teens. Scholastic Australia. Retrieved from https://www.scholastic.com/content/dam/teachers/lesson-plans/18-19/Graphic-Novel-Discussion-Guide-2018.pdf

Grazotis, J. 2017, ‘Unlocking the third space – Activating your library’, Scan 36(4), pp. 34-35. Retrieved from https://education.nsw.gov.au/teaching-and-learning/professional-learning/scan/past-issues/vol-36–2017/unlocking-the-third-space-activating-your-library

Hallman, H., & Schieble, M. (2012). Dimensions of young adult literature: Moving into “New Times”. The ALAN Review 39 (2). DOI: https://doi.org/10.21061/alan.v39i2.a.5

Kan, K. (2020). Cataloguing graphic novels [Blog]. Diamond Bookshelf. Diamond Comic Distributions. Retrieved from https://www.diamondbookshelf.com/Home/1/1/20/181?articleID=37812

Kirtz, J.L. (2014). Computers, comics and cult status: A forensics of digital graphic novels. Digital Humanities Quarterly 8 (3). Retrieved from http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/8/3/000185/000185.html

Kole, K. (2018). The role of fairy tales in affective learning: Enhancing adult literacy and learning in FE and community settings. Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 58(3), 365-389. Retrieved from https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.csu.edu.au/docview/2250950746?accountid=10344

Maniace, E. (2014). Reading process comparison between graphic novels and traditional novels. Education and Human Development Master’s theses. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.brockport.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1539&context=ehd_theses

Mozart, W.G. (Composer) & Schikaneder, E. (Librettist). (1791). Die Zauberflote – A Singspiel in 2 Acts. Vienna, Austria.

Phelps, V. (2011). Pedagogy of graphic novels. Master Theses & Specialist Projects – American Popular Culture Commons. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2070&context=theses

Schumacher, J. (2014). More ways to pitch graphic novels [Blog]. Literacy Now. International Literacy Association. Retrieved from https://www.literacyworldwide.org/blog/literacy-now/2014/08/12/more-ways-to-pitch-graphic-novels

Walsh, M. (2013). Literature in a digital environment (Ch. 13). In L. McDonald (Ed.), A literature companion for teachers. Marrickville, NSW: Primary English Teaching Association Australia (PETAA).

Wilson, J. (2019). Everything you need to know about digital comics. PC Magazine News. Retrieved from https://au.pcmag.com/features/12330/everything-you-need-to-know-about-digital-comics