Pexels / Pixabay – Classroom divide – How is your classroom divided?

For a period of time, society was of the opinion that people who grew up with technology would naturally be comfortable and confident using it as it was their native ‘language’. These technically savvy individuals would require minimal instruction on digital literacy because as a cohort, they would approach digital technologies with intuitiveness and instinct.

But that assumption was WRONG!

Not just kinda wrong ..

BUT

EPICALLY WRONG!

Think

BIGGER THAN

KIND OF WRONG.

But I digress…

The myth of the digital native and digital immigrant has been thoroughly debunked (Kirschner & De Bruyckere, 2017). They myth assumed that technology competence was inherent because of life long exposure to digital technologies (Frawley, 2020). This bias is based upon the common image of students permanently attached to their devices for social and personal practices, and does not translate to ICT proficiency in an educational setting (Brown & Czerniewicz, 2011).

GraphicMama-team / Pixabay

Day (2012) suggests that the theorised cause of the previous digital divide was between those with computer access and those without. But most teachers would disagree. Many students have access to smartphones and tablets for personal use and they are still flummoxed at using technology in their schooling. It appears there is a clear lack of translation from social use of devices and technology to educational practices. This is observable in the way students are familiar with keyboards for gaming purposes, but very few are highly accomplished at touch typing (onlinetyping.org, 2020). It amazes me how some students can deftly play online games and switch their screens in milliseconds to avoid detection, but are unable to create and save a document to find at a later date. Others can create a TikTok video, but do not understand the mechanics of boolean operators to search databases. I have students that can surf the web for hours but are unable to read an article online in depth and the list just goes on…. All these examples clearly show that any correlations of age should not be translated to an assumption of digital literacy. Digital literacy, as I have expounded on before, are the psychomotor, cognitive and affective skills required to use digital technologies successfully (McMahon, 2014, p.525). Students and their parents who are technology savvy are more adept at navigating the digital world (Day, 2012).

TheDigitalArtist / Pixabay

How the divide manifests:

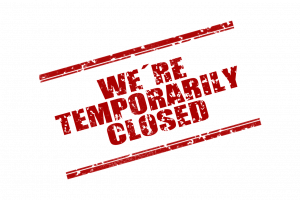

Educational professionals around the world have realised the impact the digital divide has had on learning outcomes (Steele, 2018). In Australia, the divide was previously acknowledged in educational circles but has been brought to the forefront with the recent Coronavirus pandemic and corresponding school closures. The nation wide school closures identified numerous students and their families who lacked access to personal devices and high speed internet at home (Coughlan, 2020). Some students and families did attempt to stream online learning through mobile phone data but this method proved to be unrealistic and very costly (Coughlan, 2020). Whilst most Educational Directorates across Australia provided their disadvantaged students with laptops and internet dongles, the process was often time consuming and bogged by red tape (Duffy, 2020).

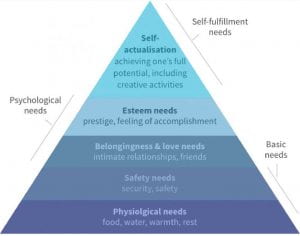

Students with a digital disadvantage often have a very different schooling experience than students who could be considered digitally elite. The digitally elite are able to study from the comfort of their couch or their bedroom, in pleasant and safe surroundings (Steele, 2018). The level of work produced by these students is higher and of better quality as they are not worrying about library opening hours, or stressed or anxious about getting home late. Whereas students who are disadvantaged may hand in poorly conducted assignments because they were unable to research under optimal conditions (Steele, 2018). Many teenagers are too embarrassed to be seen doing school work in the library when their friends are playing games, and some students who lack NBN, broadband internet and a desktop or laptop at home, persist in doing their assignments on their mobile phones, which leads to increased fatigue and eye strain. Many disadvantaged students would rather cite lack of interest in learning, or pretend to be apathetic than admit they do not have appropriate facilities at home and just stop trying to learn. When you consider Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, it is clearly obvious that a student’s self actualisation is unlikely to occur if their personal safety and security is at risk (Hopper, 2020).

Some critics would argue that personal devices such as smartphones are ubiquitous and allow anyone with a phone internet access. Sung (2016) points out that whilst mobile phones do offer internet access, it is not conducive for conducting research or in depth analysis of documents and as they tend to promote superficial features such as emails, social media and multimedia (Sung, 2016).

LoboStudioHamburg / Pixabay – Smartphones – Mostly social?

How to reduce the divide: School based programs.

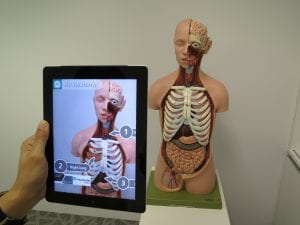

Education Magazine (2020) points out that the onus to reduce the divide are within the realm of federal and state government departments. Currently, the most common method government bodies chose to address the digital gap is to supply students with a personal device such as a laptop or tablet (Jervis-Bardy, 2020). But Steele (2018), Day (2012), and Boss (2016) all agree that bridging the divide goes beyond just supplying students with devices as simply handing each student a device does not build critical thinking and digital citizenship. But the explicit teaching of digital literacy across all learning areas, would not only have a greater impact on bridging the gap, it would also empower students to gain further digital knowledge and understanding (Steele, 2018; Lori, 2012).

Whilst teaching students digital literacy is an essential step, it is important to also involve their parents opportunities that build ICT competence and digital literacy (Wolohan, 2016; Hiefield, 2018). Wolohan (2016) suggests that when schools and communities offer digital information sessions, it affords opportunities for parents who may also have low digital literacy a chance to broaden their knowledge and learning (Boss, 2016). This then means that parents are able to assist their children with their learning at home, which improves technology integration, learning outcomes and bridges positive connections between school and home (Hiefield, 2018). These sessions could also be used to inform families of any extra facilities and services that the school offers, such as extended library hours, homework help, as well as other local facilities such as public library and other community services (Wolohan, 2016).

School libraries and teacher librarians are already involved with digital literacy pedagogical practices in numerous ways – as I have mentioned in this blog . Another engaging and innovative way to boost digital literacy are digital or coding clubs. Busteed & Sorenson (2015) suggest that lunchtime run digital clubs and programs are a fun and engaging way of teaching digital literacies and competencies at school. These clubs allow students to explore different computer programs and devices independently or in collaborative learning groups. Lunch time clubs also open the door for many students, including digitally disadvantaged students, a chance to explore emerging technologies that they may not normally get access to (Busteed & Sorenson, 2015). As these clubs are predominantly social in nature, they do not have to conform to curriculum requirements, and this means students are able to explore their own interests instead of canon. Further school based options include ensuring a bank of spare devices for students who do not have access to their own, advocating for an extension of library opening hours outside school hours to allow students time to study, as well as explicitly teaching digital literacy skills as part of teaching and learning (Education Magazine, 2020).

How to reduce the divide: Classroom based learning.

Teachers and educators should be encouraged to adapt their practices to reduce or minimise any unnecessary ‘digital’ stress on their students. Stress factors include take home assignments and feelings of overwhelm due to poor digital literacy skills. Wolohan (2016) advises teachers to get to know their cohort and understand that whilst students may appear to be confident using their devices, it is not advisable to send large assignments home unless digital literacy and ICT facilities at home are assured. Non submission of tasks could be due to lack of internet or even access to assistance from parents or caregivers, who may have low digital literacy skills and unable to assist their children with tasks (Wolohan, 2016).

The other consideration classroom teachers and teacher librarians need to make is to acknowledge that each student’s ICT ability will vary and that our learning activities need to match their competencies. This means that digital literacy needs to be differentiated the same manner as the rest of the curriculum (Wolohan, 2016). One method is to identify students’ zone of proximal development, and create learning activities that are within that zone for optimal learning (Audley, 2018). This method is far more efficient and beneficial than assuming capability or teaching at a fixed point.

CONCLUSION

Steele (2018) feels like the greatest social ramification of the digital divide is that disadvantaged students will not get the same opportunities to be creative and inventive with digital technologies. This means that the future scope of these students would be limited and possibly restricted in this new information paradigm to long term prospects of minimum wage. Whereas students on the better half of the divide have unlimited access to information in the safety and comfort of their own home, the financial stability to access emerging technologies, increased opportunities to develop interest and skills in engaging and exploring these technologies. Their long term prospects are far removed from their disadvantaged peers who often have to travel extensively to have the same access to technology and the internet. This in itself is very limiting for many students and reduces their future educational and economic prospects. As teachers and educators, we need to remember that schools are supposed to be the great equaliser, and to provide equal and equitable access to knowledge and learning. Though in reality, we all know life and education is definitely not equal. Government policies can often get influenced by political affiliations and can take time to come into effect. But we as teachers have influence in our classrooms, and our actions and practice in the classroom can make a difference to improve the digital literacy of our students, improve student learning and reduce the width and depth of the digital divide.

REFERENCES:

Audley, S. (2018). Partners as scaffolds. Teaching in the zone of proximal development. Teaching and Learning Together in Higher Education. 24. Retrieved from https://repository.brynmawr.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1186&context=tlthe

Boss, S. (2016). Engage parents as partners to close digital divide. Edutopia – Digital Divide [Blog]. Retrieved from https://www.edutopia.org/blog/engage-parents-partners-close-digital-divide-suzie-boss

Brown, C., & Czerniewicz, L. (2010) Debunking the digital native beyond digital apartheid, towards digital democracy. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning (26) 5. p357-369. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2729.2010.00369.x

Busteed, B., & Sorenson, S. (2015). Many students lack access to computer science learning. Gallup Education. Retrieved from https://www.gallup.com/education/243416/students-lack-access-computer-science-learning.aspx

Coughlan, S. (2020). Digital poverty in schools where few have laptops. BBC News – Family and Education. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/education-52399589

Day, L. (2013). Bridging the new digital divide. Edutopia – Technology Integration [Blog]. Retrieved from https://www.edutopia.org/blog/bridging-the-new-digital-divide-lori-day

Duffy, C. (2020). Coronavirus opens up Australia’s digital divide with many school students left behind. ABC News. Retrieved from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-05-12/coronavirus-covid19-remote-learning-students-digital-divide/12234454

Education Magazine. (2020). What is the digital divide and how is it impacting the education sector? The Education Magazine [blog]. Retrieved from https://www.theeducationmagazine.com/word-art/digital-divide-impacting-education-sector/

Frawley, J. (2017). The myth of the digital native. Teaching @ Sydney [blog]. University of Sydney. Retrieved from https://educational-innovation.sydney.edu.au/teaching@sydney/digital-native-myth/

Hiefield, M. (2018). Family tech nights can narrow the digital divide. E-School News. Retrieved from https://www.eschoolnews.com/2018/11/21/family-tech-nights-can-narrow-the-digital-divide/

Hopper, E. (2020). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. ThoughtCo. Retrieved from https://www.thoughtco.com/maslows-hierarchy-of-needs-4582571

Kirschner, P., & De Bruyckere, P. (2017). The myths of the digital native and the multitasker. Teaching and Teacher Education 67, p.135-14

McMahon, M. (2014). Ensuring the development of digital literacy in higher education curricula. ECU Publications. Edith Cowan University. Retrieved from https://ro.ecu.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1835&context=ecuworkspost2013

Online Typing.org. (2020). Average typing speed (WPM)[blog]. Retrieved from https://onlinetyping.org/blog/average-typing-speed.php

Sung, K. (2016). What’s lost when kids are under connected to the internet? KQED – Mindshift. Retrieved from https://www.kqed.org/mindshift/43601/whats-lost-when-kids-are-under-connected-to-the-internet

Steele, C. (2018). 5 ways the digital divide effects education. Digital Divide Council. Retrieved from http://www.digitaldividecouncil.com/digital-divide-effects-on-education/

Wolohan, S. (2016). How teachers can provide equal learning in a world of unequal access. EdSurge – Diversity and Equity. Retrieved from https://www.edsurge.com/news/2016-04-13-how-teachers-can-provide-equal-learning-in-a-world-of-unequal-access