Graphic Organisers in Inquiry Learning – Facilitating the critical thinking process.

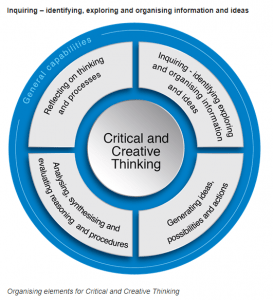

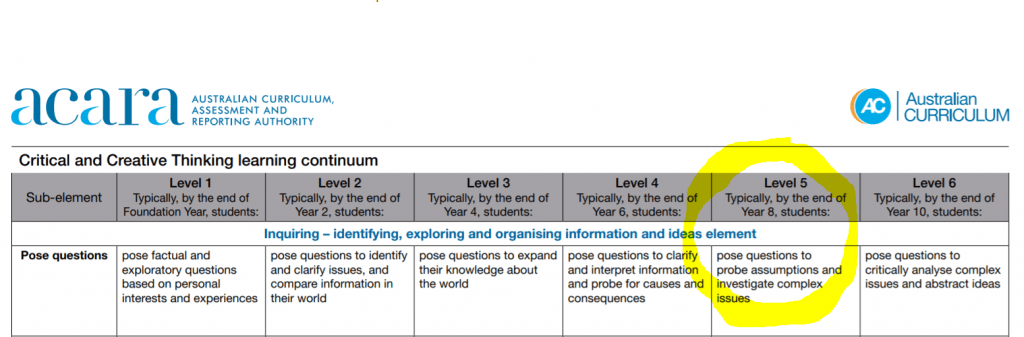

Figure 1. (ACARA, 2016) Critical and Creative Thinking.

The ability to pose a question is clearly detailed in ACARA (2016) General Capabilities – Critical and Creative Thinking as a stimulus to learning. Students are challenged to create a rigorous question that can be challenged, examined and analysed to provide useful information for the investigator to draw a conclusion (Rattan, Anand & Rantan, 2019; Werder, 2016; Aslam & Emmanuel, 2010). Werder (2016) in particular argues that inquiry questions need to contain specific disciplinary languages and parameters that define the depth and breadth of the learning experience. Unfortunately, many of the questions constructed by students fall short of this standard because they struggle in developing inquiry questions that are sufficiently open-ended for further investigation, yet within the parameters of their task. This quagmire led to the discussion of using a graphic organiser to scaffold the students into forming an appropriate inquiry question.

Figure 1 – ACARA (2016) Critical and creative thinking continuum.

Figure 1 – ACARA (2016) Critical and creative thinking continuum.

Theory of Graphic Organisers – Framework for critical thinking.

Language, literacy and learning are greatly improved when graphic organisers are used as they allow for the collection, curation and construction of information in categorical, comparative, sequential or hierarchical organisation (Ilter, 2016, p.42; Lusk, 2014, p.12). Graphic organisers are a constructivist approach to learning because the chart encourages students to write as a method of constructing their knowledge, and can be used to introduce a topic, activate prior knowledge, curate information, connect ideas and concepts, as well as visually present information and assess student understanding (Cox, 2020; Lusk, 2014). They are effective across all year levels, curriculum areas, as well as in educational, personal or professional spheres of life as their efficacy lies in their structure (Cox, 2020). Graphic organisers are diverse and can range from maps, diagrams, tables, and charts, with venn diagrams, concept maps, tables and T-charts are the most frequently used in classroom settings (Cox, 2020).

Graphic organisers allow for the holistic understanding of a topic by allowing challenging concepts to be displayed in a meaningful manner (Lusk, 2014, p.11). Students are able to visually see the breadth and depth of their learning and this can be particularly useful for scaffolding more challenging concepts or to assist low ability students. This visual organisation is especially important for disciplinary literacy development, accumulation of knowledge and the comprehension of challenging concepts (Werder, 2016, p.2; Ilter, 2016, p.42).

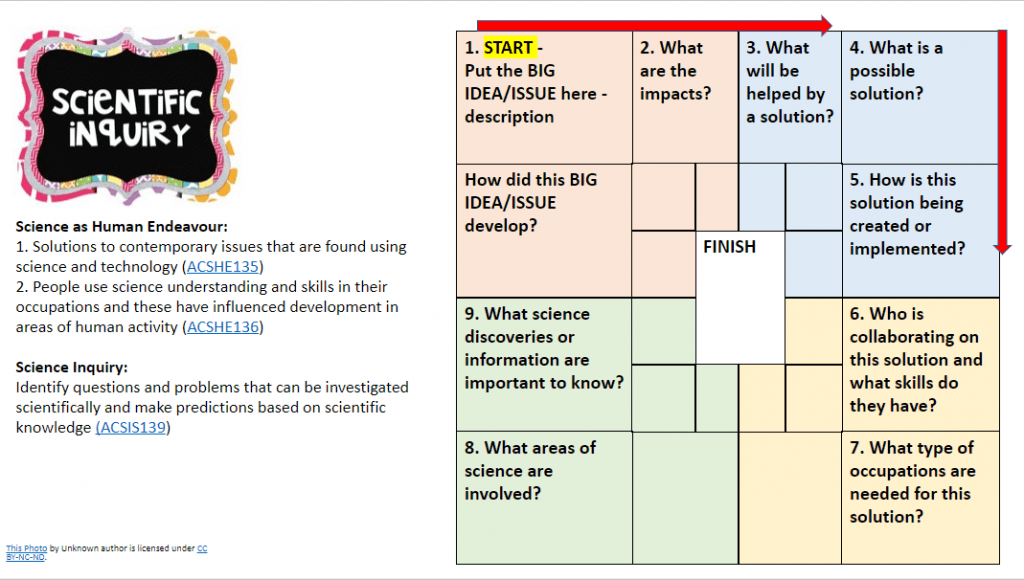

Science Learning Outcomes:

Science as Human Endeavour

- Solutions to contemporary issues that are found using science and technology (ACSHE135)

- People use science understanding and skills in their occupations and these have influenced development in areas of human activity (ACSHE136)

Science Inquiry:

- Identify questions and problems that can be investigated scientifically and make predictions based on scientific knowledge (ACSIS139)

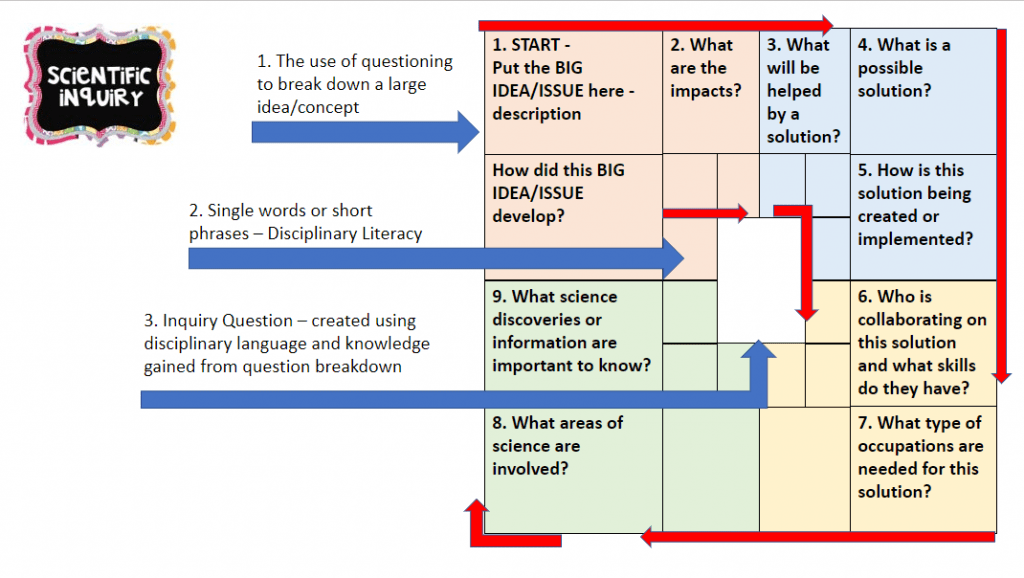

The year 8 guided inquiry unit was constructed collaboratively between the Science team leader RW and the Teacher librarian. The goal was to scaffold the students into creating inquiry questions that were of a high standard within the defined boundaries of the task. The Teacher Librarian conceived the idea of using a graphic organiser, and then worked collaboratively with the Science Team Leader to frame and integrate the questions within the chart. The end result was a chart that used a layer of questions to build connections between prior knowledge and new information; before narrowing down to identifying relevant disciplinary literacy which is then used to formulate the scientific inquiry question. As many of the science teachers were unfamiliar with the GID process, a joint decision was made by the Teacher librarian and the Science team leader that certain sections of the inquiry would be team taught by the classroom teacher and a teacher librarian. The entire year 8 science cohort of ten classes utilised the library for five consecutive lessons each. This collaborative practice supported both the teacher in their practice and the student in their learning.

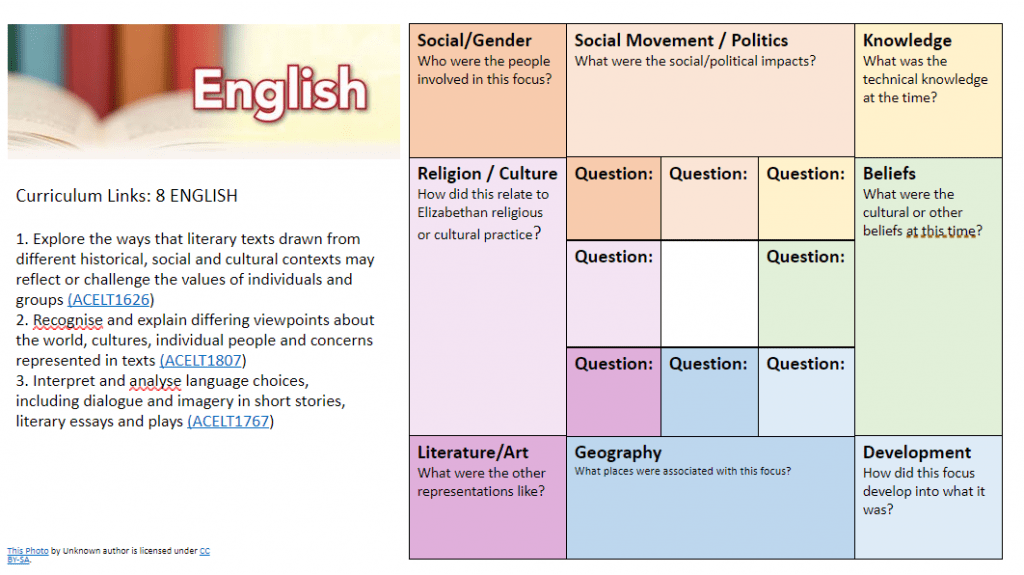

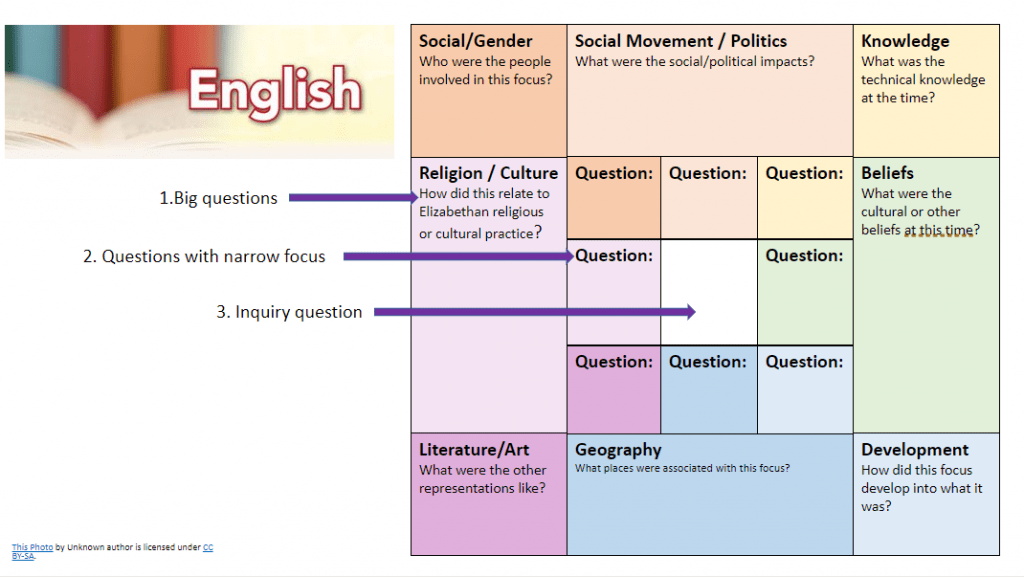

English Learning Outcomes:

- Explore the ways that literary texts drawn from different historical, social and cultural contexts may reflect or challenge the values of individuals and groups (ACELT1626)

- Recognise and explain differing viewpoints about the world, cultures, individual people and concerns represented in texts (ACELT1807)

- Interpret and analyse language choices, including dialogue and imagery in short stories, literary essays and plays (ACELT1767)

The success of the Science modified lotus chart inspired the English team leader CB to create a similar one but instead of using a single layer of questioning, CB decided the students needed to funnel down from a broad focus to a narrow focus before coming to their inquiry question. This meant that students were asked to look deeper into the various perspectives of Shakespeare’s World and then pose a series of questions before arriving at their main inquiry question. At this point the students were familiar with the concept of inquiry learning but there was still some uncertainty from the classroom teachers. Therefore, the English team leader CB suggested that the classes be brought to the library so that they could be supported by the teacher librarians. Unfortunately, there was less uptake from the English department in comparison to the science team, and this meant only a few teachers were willing to work collaboratively in a flexible learning space.

For both the Year 8 inquiry tasks, the modified lotus chart was integrated into the learning journal and included questions of varying cognitive levels to scaffold learning, promote metacognition, elicit writing for meaning, and facilitate the formulation of a robust inquiry question (Tofade, Elsner & Haines, 2013). Most students received the standard chart and questions, but those with additional needs were offered supplementary cognitive scaffolding, and highly adept students were given the opportunity to create their questions for a self-directed approach (Lusk, 2014, p.12). The integration of questioning increased the success of the inquiry task as it promoted metacognition, differentiated the learning, minimised accidental sedge ways, developed disciplinary vocabulary and allowed students to stay within the learning goal parameters. Another advantage is that the questions within the chart were task, rather than subject specific, which meant that students were able to engage in learning based on their own interests rather than predetermined topics (Werder, 2016).

Evaluating the impact of the graphic organiser on the learning process.

SCIENCE INQUIRY TASK –

The student’s ability to create a question that was specific, yet with enough depth to allow for an open-ended investigation was assessed both informally and formally. Initially, the question was informally assessed by the classroom teacher and teacher librarian for its suitability before the students could proceed to the next step in their inquiry task. In most circumstances, the question that was too broad and or too difficult for students to investigate successfully in their limited time frame. This meant that students were asked to go back and use the questions to extend their thinking processes and narrow down their investigation parameters. They also had to clearly illustrate their cognitive process through their modified lotus graphic organiser as part of their formal and summative assessment of learning identified within the task rubric. Anecdotal evidence from classroom teachers suggests that students seemed more prepared, and their questions were of a higher quality in comparison to previous years where there was no graphic organiser used.

ENGLISH INQUIRY TASK –

The English inquiry question was also informally assessed by the classroom teacher and the teacher librarian to their suitability during class time. Like the science inquiry task, students used the modified lotus to formulate a question that was narrow enough to be completed within the time frame, but yet open-ended enough to investigate. The main difference between the two inquiry tasks was that the English chart requested students use two levels of questioning to develop their inquiry question. This proved to be more problematic than requesting disciplinary literacy from the middle layer, as students often needed guidance to understand that they were supposed to narrow into specifics at that point. This confusion was exacerbated by the fact the English task immediately followed the science inquiry but the change in lotus chart format caused some teacher and student anxiety. In similar circumstances to the Science inquiry, the questions formulated by the students were of a higher quality than when the modified lotus graphic organiser was not included.

Reflection of learning process

The inclusion of a modified lotus chart with an embedded line of questioning was a crucial factor in the student’s ability to formulate a suitable inquiry question because it allowed for the clear visualisation of parameters, alternative perspectives and integrated essential disciplinary literacy. It enabled students to effectively plan their investigations, identify gaps in their own reasoning, organise their thinking process and reflect upon their learning. The chart also mitigated teacher anxiety about unaddressed learning outcomes and unexpectedly promoted low stakes writing.

Many classroom teachers were concerned that a student centred inquiry task would lead to tangent investigations and lost learning outcomes. However, the modified lotus diagram allowed teachers to guide their student’s learning by using the questions to lead the students directly to the desired learning outcomes and the formulation of an appropriate question and investigation. Anecdotal evidence showed that previously reluctant teachers were satisfied with this process and were amenable to using a modified lotus for future inquiry investigations.

One of the unexpected advantages that the modified lotus diagram provided was the students were able to engage in low stakes writing. Werder (2016) points out that writing in schools is often a high stakes activity as students are often required to know the information prior to being questioned in settings, such as within exams and assignments. Cunningham (2019) elaborates upon this and calls it ‘writing to show learning’ but points out that rarely do students get to engage in ‘writing to learn’ (p.76). This means that students are seldom given opportunities to engage in writing that allows them to promote critical thinking, build content knowledge and make meaning in environments that are context rich, and situational without the pressure of assessment (Cunningham, 2019, p.79). This can be particularly an issue in high schools where students are less likely to participate in free writing. Therefore by integrating a modified lotus graphic organiser into an inquiry task, teachers are encouraging to develop their cognitive strength by connecting concepts, making meaning and creating new knowledge (Cunningham, 2019; Werder, 2016, p. 2).

Conclusion

The inclusion of a modified lotus diagram with an embedded line of questioning was very beneficial to both the faculty staff members and the students. It increased the quality of inquiry questions because the graphic organiser allowed the students to develop an understanding of the topic, which then led to a creation of a question that can be challenged, examined and investigated more deeply. The format of the diagram also ensured that the students developed disciplinary literacy and addressed the learning outcomes as required. Interestingly, the unexpected outcome of low stakes writing proved to be very beneficial to the learning process and as such, future graphic organisers will be constructed to provide ample writing space.

References:

ACARA. (2016). F –10 Curriculum – Science Curriculum. Educational Services Australia. https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/science/

ACARA. (2016). Critical and creative thinking continuum. F-10 Curriculum – General Capabilities. Educational Services Australia. https://australiancurriculum.edu.au/media/1072/general-capabilities-creative-and-critical-thinking-learning-continuum.pdf

Andrini, V.S. (2016). The effectiveness of inquiry learning method to enhance student’s learning outcome: A theoretical and empirical review. Journal of Education and Practice 7(3). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1089825.pdf

Aslam, S., & Emmanuel, P. (2010). Formulating a researchable question: A critical step for facilitating good clinical research. Indian journal of sexually transmitted diseases and AIDS, 31(1), 47–50. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3140151/

Brookhart, S. (2013). Chapter 1 – What are rubrics and why are they important. In How to Create and Use Rubrics for Formative Assessment and Grading. ASCD. http://www.ascd.org/publications/books/112001/chapters/What-Are-Rubrics-and-Why-Are-They-Important%C2%A2.aspx

Cox, J. (September 16, 2020). What is a graphic organiser and how to use it effectively. TeacherHub.com [Blog]. https://www.teachhub.com/classroom-management/2020/09/what-is-a-graphic-organizer-and-how-to-use-it-effectively/

Cunningham, E. (2019). Teaching invention: Leveraging the power of low stakes writing. The Journal of Writing Teacher Education 6(1). 76-87. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1180&context=wte

Ilter, I. (2016). The power of graphic organisers: Effects on students’ word learning and achievement emotions in social studies. Australian Journal of Teacher Education 41(1), p42-64.

Kilickaya, F. (2019). Review of studies on graphic organisers and language learner performance. APACALL Newsletter 23. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED602371.pdf

Lusk, K. (2014). Teaching High School Students Scientific Concepts Using Graphic Organizers. Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. 895. https://mds.marshall.edu/etd/895

Maniotes, L., & Kuhlthau, C. (2014) Making the shift. Knowledge Quest. 43(2) 8-17. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1045936

Maxwell, S. (2008). Using rubrics to support graded assessment in a competency based Environment. National Centre for Vocational Education Research. Commonwealth of Australia – Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. https://www.ncver.edu.au/__data/assets/file/0012/3900/2236.pdf

NSW Department of Education. (2021). Strategies for student self assessment. Teaching and Learning – Professional Learning. Retrieved from https://education.nsw.gov.au/teaching-and-learning/professional-learning/teacher-quality-and-accreditation/strong-start-great-teachers/refining-practice/peer-and-self-assessment-for-students/strategies-for-student-self-assessment

Quigley, C., Marshall, J., Deaton, C.C.M., Cook, M.P., & Padilla, M. (2011). Challenges to inquiry teaching and suggestion for how to meet them. Science Education (20) 1; p55-61. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ940939.pdf

Ratan, S. K., Anand, T., & Ratan, J. (2019). Formulation of Research Question – Stepwise Approach. Journal of Indian Association of Pediatric Surgeons, 24(1), 15–20. https://doi.org/10.4103/jiaps.JIAPS_76_18

Southen Cross University. (2020). Using rubrics in student assessment. Teaching and Learning. https://www.scu.edu.au/media/scueduau/staff/teaching-and-learning/using_rubrics_in_student_assessment.pdf

State Library of Victoria. (2021). Generating questions – lotus diagram. ERGO – Research Resources. Retrieved from http://ergo.slv.vic.gov.au/teachers/generating-questions-lotus-diagram

Stone, E. (2014). Guiding students to develop an understanding of scientific inquiry: A science skills approach to instruction and assessment. CBE Life Science Education 13 (1): pp90-101. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3940468/

Tofade, T., Elsner, J., & Haines, S. T. (2013). Best practice strategies for effective use of questions as a teaching tool. American journal of pharmaceutical education, 77(7), 155. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe777155

Vale R. D. (2013). The value of asking questions. Molecular biology of the cell, 24(6), 680–682. https://doi.org/10.1091/mbc.E12-09-0660. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3596240/

Werder, C. (2016). Chapter 10 – Writing as inquiry, writing as thinking. The Research Process: Strategies for undergraduate students. 10. Retrieved from https://cedar.wwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=http://www.jurn.org/&httpsredir=1&article=1009&context=research_process

Wilson, N.S., & Smetana, L. (2011). Questioning as thinking: a metacognitive framework to improve comprehension of expository text. Literacy 45(2). UKLA.

Zion, M., & Mendelovici, R. (2012). Moving from structured to open inquiry: Challenges and limits. Science Education International 23(4): p383-399. International Council of Associations for Science Education. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1001631.pdf