geralt / Pixabay

Multimedia is the convergence of multiple forms of media into one format and is present across all aspects of modern life including classroom practice.

The notion of a multimedia resource may seem to be a more modern construct, but multimedia resources have been associated with educational practices for an extended period of time. Originally appearing in classrooms as annotated drawings, maps, and picture books, these static forms of multimedia appear in many guises, across all learning areas and year levels (Ibrahim, 2020).

Multimodality is cited as a panacea for pedagogical problems, both inside and outside the classroom. In fact, the prevalence of multimodal resources in education has been adduced as more effective at communicating information than when a single modality is used (David, 2020). This is because the information is often delivered in two main literacies, visual and auditory. It is the combination of these literacies that enhances learning, and improves educational outcomes (Ibrahim, 2012). But not all multimedia resources promote learning. The method and delivery of the information is essential to ensure students do not suffer from information overload.

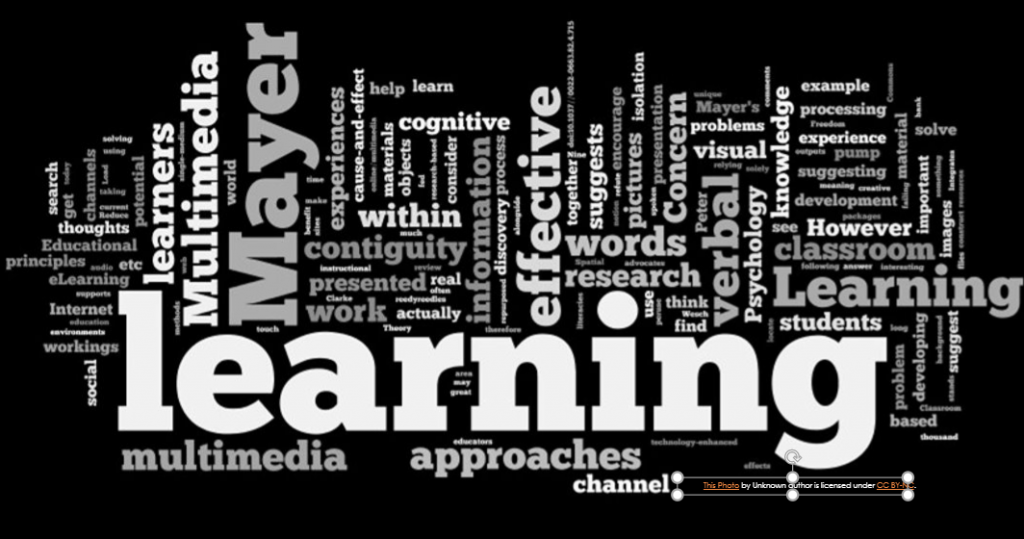

A modern classroom is likely to have multimodal resources in a variety of formats, ranging from static formats such as picture books, to illustrated books, graphic novels and anime, to more dynamic forms such as videos, interactive websites and videos (Ibrahim, 2020). The use of common teaching tools such as Powerpoint, digital textbooks, ebooks, websites and databases can all be considered dynamic forms of multimedia (Ibrahim, 2012). The efficacy of multimodal learning is based upon two main theories, Mayer’s cognitive theory of multimedia learning and Sweller’s cognitive load theory (Ibrahim, 2012). These two theories are able to predict which parameters of multimedia lead to optimum intellectual performance (Heick, 2017).

Mayer’s theory pointed out that whilst the brain appears to engage with material simultaneously, it instead selects the information individually and then organises and integrates the data consequently in three distinct cognitive processes (Mayer & Moreno, 2005). The first step in this process is that the learner selects an amount of incoming auditory and visual information to process. This amount is finite and an overload of information can have negative ramifications for the student such as confusion and a distaste for that medium (David ,2020). The next step in this cognitive process is the organisation of that processed information. This is where the user merges the visual and auditory information together (Mayer & Moreno, 2005; David 2020). Both Ibrahim (2012) and David (2020) agree when modalities complement and enhance each other, as the visual imagery allows the brain to use its cognitive strength to work towards constructing working schemas instead of creating a mental image. Creating mental images is cognitively heavy and the construction of schemas decreases the cognitive load on a learner and increases working memory. The last step is where the learner integrates and constructs new knowledge on their own prior learning to make meaning of this new information (Mayer & Moreno, 2005; David 2020). Ibrahim (2012) believes that by constructing their own meaning, the learner is able to increase their overall understanding and comprehension of the content.

ArtsyBee / Pixabay

Sweller’s cognitive load theory is based upon the structure and process of the human memory system which includes the method in which memories, information and knowledge are stored in a complex and integrated manner (Russell, 2019). When a learner is presented with new information, their working memory has a limited capacity unless it is transferred to their limitless long term memory (Russell, 2019). This finite capacity in the working memory cache, also known as cognitive load, has direct implications on the learning in classrooms. CESE (2017) categorises cognitive load as intrinsic, extraneous and germane. Intrinsic cognitive load is from the inherent complexity of the information, and can be supported by germane load, which are instructions that facilitate the transfer of knowledge from the working memory to the long term memory (CESE, 2017, p.3). Whereas extraneous load inhibits memory transfer and does not contribute to positive learning outcomes (CESE, 2017, p.3). As Russell (2019) points out, the cognitive load theory indicates that explicit instruction is required to transfer learning from the working memory to the long term memory and requires explicit instruction and worked examples to ensure learners are capable of developing their own knowledge base and long term memory (Russell, 2019).

ArtsyBee / Pixabay

These two theories have a direct implication on the construction and delivery of multimedia and multimodal resources in the classroom. Mayer’s concept of cognitive loading of multimedia uses Sweller’s cognitive load theory to determine the point where retention and comprehension are optimised (Xie et al., 2017, p.14) Mayer’s theory of visual and auditory information being processed separately is an extension of the split attention effect known as the modality effect (CESE, 2017, p.7). Split attention contributes to cognitive loading, as it often requires the learner to process pieces of information simultaneously for integration. Whereas the modality effect actually reduces the load, because the same information is presented in two forms and thus increases the working memory capacity (CESE, 2017, p.7). This fact is further emphasised when students engage in collaborative learning. Kirscher et al, (2018, p.222) argue that when the task is cognitively heavy, collaborative groups are beneficial if the individual members are capable of utilising their combined capacity. Whilst many teachers are familiar with the structure, function and benefits of collaborative learning groups in classrooms, they need to ensure distribution of cognitive loading occurs for optimal learning.

manfredsteger / Pixabay

Mayer’s theory of multimodal or multimedia learning is structured around several principles (Walsh, 2017). Whilst the principles do vary in their focus, the overall arching theme is that users or students would statistically learn better if unessential content is removed, clues highlighted or signalled, words and texts are presented simultaneously rather than consecutively (Walsh, 2017; Ibrahim, 2012). Xie et al., (2017) determined that cues are essential in dynamic resources to minimise cognitive load, but that their presence improves knowledge retention and transfer in static and dynamic forms of multimedia. Ibrahim (2012) also points out that the efficacy of multimodal resources is increased dramatically when the format is segmented or promotes self pacing, and if the narrator’s voice uses colloquial language and a conversational style compared to formal structure and tone (Walsh, 2017). These principles help educators in creating and determine which multimedia resources would benefit student learning and which ones inhibit it.

Multimedia, multimodal learning and resources are an essential part of modern pedagogical practices. Their presence in both static and dynamic forms are present in all aspects of teaching practices. Therefore it behooves the educator to understand how the brain interacts with these resources. Resources that cause information or cognitive overload to students impede learning as the user is working against the brain, rather than with the brain (Heick, 2017). Multimedia designed within the parameters of Mayer’s and Sweller’s theories have an increased efficacy with learning outcomes than multimodal resources without it.

REFERENCES

Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation. (2017). Cognitive load theory: Research that teachers really need to understand. NSW Department of Education. Retrieved from https://www.cese.nsw.gov.au//images/stories/PDF/cognitive-load-theory-VR_AA3.pdf

David, L. (2020). Cognitive theory of multimedia learning (Mayer). Learning Theories. Retrieved from https://www.learning-theories.com/cognitive-theory-of-multimedia-learning-mayer.html

Heick, T. (2017). What is cognitive load theory? A definition for teachers. TeachThought. Retrieved from https://www.teachthought.com/learning/cognitive-load-theory-definition-teachers/

Ibrahim, M. (2012). Implications of designing instructional video using cognitive theory of multimedia learning. Critical Questions in Education 3(2), p.83-104. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1047003

Kirschner, P., Sweller, J., Kirschner, F. & Zambrano, J. (2018). From cognitive load theory to collaborative cognitive load theory. International Journal of Computer Supported Collaborative Learning 13, p.213-233. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-018-9277-y

Lloyd, T., Mitchell, B., & Mayers, R. (2012). Overall, Excellent Work! Assessment Rubric for Learning Theories. Paper Exceptional Satisfactory Developing Inadequate a (90%-100%) B (80%-89%) C (70%-79%) D/f (0-69%).

Mayer, R., & Moreno, R. (2005). A cognitive theory of multimedia learning; Implications for design principles. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/248528255_A_Cognitive_Theory_of_Multimedia_Learning_Implications_for_Design_Principles

Mayer, R., & Moreno, R. (1998). A Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning: Implications for Design Principles. CHI 1998. DOI:10.1177/1463499606066892

Russell, D. (2019). An introduction to cognitive load theory. Teacher Magazine [Features]. Retrieved from https://www.teachermagazine.com.au/articles/an-introduction-to-cognitive-load-theory

Sweller, J., van Merriënboer, J.J.G., & Paas, F. (2019). Cognitive Architecture and Instructional Design: 20 Years Later. Educational Psycholgy Review 31, p261–292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09465-5

Walsh, K. (2017). Mayer’s 12 principles of multimedia learning are a powerful design resource [Blog]. Emerging EdTech. Retrieved from https://www.emergingedtech.com/2017/06/mayers-12-principles-of-multimedia-learning-are-a-powerful-design-resource/

Xie H, Wang F, Hao Y, Chen J, An J, Wang Y, et al. (2017). The more total cognitive load is reduced by cues, the better retention and transfer of multimedia learning: A meta-analysis and two meta-regression analyses. Public Library of Science ONE 12 (8). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pone.0183884