Text sets – Literary learning in miniature.

Free-Photos / Pixabay

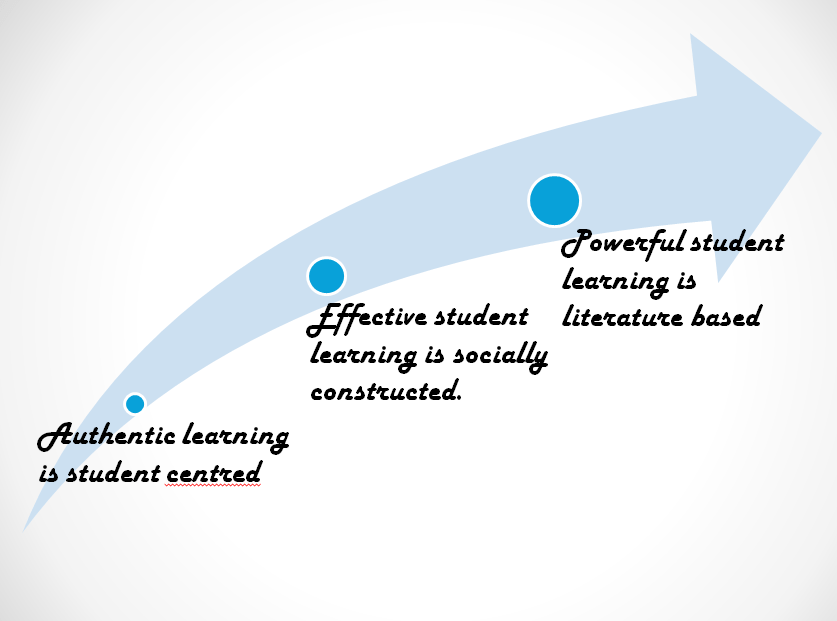

The selection of texts is an intrinsic part of education, yet finding appropriate and authentic resources that meet the needs of a diverse classroom can be very challenging for classroom teachers (Cervetti & Hiebert, 2019; Lupo et al., 2019). This difficulty arises from a combination of poor literacy skills, reading reluctance and academic disinterest, which has forced teachers to seek additional methods to facilitate learning (Elish-Piper et al., 2014, p.565). Theoretically similar to literary learning, text sets are collated using learning outcomes, curriculum links or themes and seek to develop literacy, language and learning in a social context (Derewianka, 2015). This strategy is an effective literacy tactic that addresses teacher concerns as well as meets the needs of a diverse classroom, develops critical thinking, promotes multimodal literacy, collaborative learning, and can be successfully integrated across the curriculum.

Definition

Text sets are a range of resources that is designed for collaborative learning and is specifically curated to address a learning outcome for a cohort of students (Beck, 2014, p. 13). At its most basic form, text sets are composed of four different textual elements and can be physical, digital or multimodal in nature (Hoch, et al., 2018, p. 701). The efficacy of text sets is increased in social learning environments as it is designed for collaborative learning groups (Beck, 2014, p.13). Like literary learning, text sets use a variety of genres to give students a diverse perspective, but their difference is in that literary learning uses entire pieces of literature to facilitate learning, whereas text sets are collated extracts that will vary in length, literacy level and structure (Beck, 2014, p.13). The first element, or main text, is aimed at the median class cohort literacy and contains most of the relevant information, with the remaining sets used to support the targeted text’s comprehension (Lewis & Strong, 2020, p.47). These sets should include a motivation component in a digital, visual or interactive format; an informational portion that provides additional background knowledge; and an accessible element drawn from popular culture (Lewis & Strong, 2020, p.47). It is important to note that for teenagers, it is the accessible text that the students use to make connections between themselves, the text and their world, thus placing the learning in that essential third space (Elish-Piper, 2014, p.565; Lewis & Strong, 2020, p.47).

Theory

Text sets and literary learning are an extension of Vygotsky’s and Halliday’s theory that language, literacy and learning develops in a social context (Derewianka, 2015). This theory, known as genre theory acknowledges that each genre has its own format and thus will showcase different aspects so that students are able to discourse in greater depth on the subject matter (Derewianka, 2015). Historically single class texts have been used as a foundation for student learning in the form of textbooks and class novels. But this dynamic is problematic in a modern classroom as the average Australian classroom contains a range and breadth of abilities and needs and textbooks are generally aimed at a specific year level (Beck, 2014, p.12). The other pertinent issue is that students are unable to perceive multiple perspectives from a single text viewpoint and this is particularly salient for the teaching and learning of history and science, where bias and perspectives can have significant impact on the reader (Beck 2014, p.12).

Benefits

There are several literacy benefits to the incorporation of text sets in pedagogical practices. These include, increasing reading volume, improving text diversity, the provision of covert scaffolding, as well as expanding perspectives and connections (Lewis & Strong, 2020, p.41; Lupo et al., 2019; Elish-Piper et al., 2014). A notable positive of text set usage is that it increases the reading volume. Many teachers minimise reading by providing textless information in the form of powerpoints to reduce the cognitive load of their students. Unfortunately, the removal of texts is detrimental to literacy development, as reading volume is correlated to comprehension, vocabulary knowledge, disciplinary literacy as well as reading stamina (Lewis & Strong, 2020, p.41).

Text diversity is a natural consequence of text sets as the inclusion of literary fiction and fictional narratives introduce students to new and complex concepts and perspectives in a storytelling format; whereas informational texts scaffold students with additional background information for understanding challenging concepts (Derewianka, 2015; Elish-Piper et al., 2014, p. 567). Diversity in texts also exposes students to varying forms of literature that they may not normally experience, which in itself promotes literacy development (Lupo et al., 2019, p.514). Another merit is that text sets increase the number of connections a student will make with the text and thus increase their overall comprehension and understanding of the content within the text (Lewis & Strong, 2020, p.43).

Impact

Text sets align with Australian educational values as they are child centred and constructivist in nature as students are required to utilise a span of literacy strategies to construct and compose their own meaning (Elish-Piper et al., 2014, p. 567). This construction of meaning occurs in two steps. Firstly, the variety and range of texts increase the number of connections between students and the texts, and thus allows them to go past the alphabet and construct their own knowledge (Lewis & Strong, 2020, p.44). Secondly, the explicit instruction of literacy strategies before, during and after reading the texts promotes analysis and coalescence of the information within the texts. Teachers can facilitate reconciliation of prior and new knowledge by requiring students to compose their own analysis, discussions, evaluation, or summarisation (Lewis & Strong, 2020, p.49). These compositions allow students to engage in low stake writing which increases their ability to make connections and construct their own meaning from the texts (Werder, 2016). They also offer valuable opportunities for formative assessment and student feedback. In fact the greatest educational benefit arises from the explicit instruction of literacy strategies whilst using the text sets in a student centred manner (Lewis & Strong, 2020, p.41; Lupo et al., 2019, p.520). This shows that text sets can be effectively administered and utilised across the curriculum to effectively teach content and bolster literacy and improve learning outcomes.

Example 1: SCIENCE

The use of text sets in science classrooms has significant benefits for teaching and learning (Manie, Mabin & Liebenberg, 2018, p.389). Science textbooks often contain information at a superficial level and their format does not take into concern the developmental age of students (Lewis & Strong, 2020, p. 43). Their information overloaded pages often overwhelm low ability students, and the lack of varied viewpoints minimise opportunities for critical thinking (Lewis & Strong, 2020). The inclusion of text sets in classroom practice provides the students with a range of viewpoints and experiences, as well as engaging disinterested students, developing critical thinking, connecting students to the curriculum and improving disciplinary literacy (Lewis & Strong, 2020; Mania, Mabin & Liebenberg (2018).

Critical thinking in particular is increased when literary texts are used because it encourages students to develop empathy, use their imaginations to explore various perspectives and challenge what is considered normal (Mania, Mabin & Liebenberg, 2018, p.391). In particular, the use of science fiction text extracts allows teachers to combine storytelling with factual science to increase student engagement with the content, provide information in diverse formats and encourage students to envisage future scientific possibilities and their effect on society (Mania, Mabin & Liebenberg, 2018, p.391; Creighton, 2014). This is because science fiction highlights the human response and how science and technologies can be used and misused. The most famous of all these science prophets was Jules Verne who imagined space, underground and underwater exploration in the mid 1800’s. His fictional journeys to the bottom of the ocean, centre of the earth and other space broke social norms and spurred others into creating innovative machines over the past two centuries. Kay (2012) points out that Verne’s scientific calculations in his journey to the moon were only marginally different from the correct calculations of Apollo 11. Whereas, non fiction narratives such as Shetterly’s Hidden Figures (2016) shows how women can challenge racial and gender stereotypes in STEM courses.

Example 2: English

Novel studies in English could be greatly advantaged by the inclusion of text sets. A single class text for a novel study can be simultaneously daunting to low literacy and low ability students, and great frustration to advanced and adept readers. The other issue is that many students lack sufficient background knowledge to fully understand the author’s intent, themes and storyline. Text sets have the ability to put the novel and author’s intent into context as well as provide important background information that allows the student to make sense of the textual components. Harper Lee’s “To kill a mockingbird’’ and Shakespeare’s “Macbeth” can be very challenging for students to comprehend, but the inclusion of text sets allows students to develop that prior knowledge and make those valuable connections to improve overall engagement and understanding of the novel (Lewis & Strong, 2020, p.46). Including information about segregation in the American south or Jim Crow’s laws, a brief biography of Rosa Parks or even an extract from Martin Luther King Jr’s “I have a dream” speech would help place Lee’s novel in context. Likewise, using Woodward and Bernstein’s “All the President’s men” with “Macbeth” would help put the classic text into context of political power and corruption and interestingly, Howell (2016) suggests that embedding nonfiction such as the science of psychosis, hallucinations and sleepwalking, as well as Jacobean era misogyny with further support students trying to understand the plot to a deeper level.

Whilst there is evidence illustrating the efficacy of text sets in the study of literature, there are some teachers who believe that the study of an individual text is in itself a developmental milestone and an important reading experience. Whilst this is true, Lewis and Strong (2020) do point out that a single viewpoint reduces the number of meaningful connections made, and therefore minimises the variety of human perspectives that can be experienced (p.43). Therefore, the use of text sets in an English classroom allows the teacher to use more complex and challenging texts for their practice, as they are able to scaffold them appropriately and thus ultimately improve the overall literacy ability of their students.

Novel Study Year 10 Learning outcomes:

- Compare and evaluate a range of representations of individuals and groups in different historical, social and cultural contexts (ACELT1639

- Evaluate the social, moral and ethical positions represented in texts (ACELT1812

- Identify, explain and discuss how narrative viewpoint, structure, characterisation and devices including analogy and satire shape different interpretations and responses to a text (ACELT1642

- Analyse and evaluate text structures and language features of literary texts and make relevant thematic and intertextual connections with other texts (ACELT1774

Text analysis: Biographies and Memoirs

Year 10 Learning outcomes:

- Understand how language use can have inclusive and exclusive social effects, and can empower or disempower people (ACELA1564

- Analyse and explain how text structures, language features and visual features of texts and the context in which texts are experienced may influence audience response (ACELT1641

- Identify, explain and discuss how narrative viewpoint, structure, characterisation and devices including analogy and satire shape different interpretations and responses to a text (ACELT1642

- Understand that people’s evaluations of texts are influenced by their value systems, the context and the purpose and mode of communication – ACELA1565

- Analyse and evaluate text structures and language features of literary texts and make relevant thematic and intertextual connections with other texts (ACELT1774

- Identify and explore the purposes and effects of different text structures and language features of spoken texts, and use this knowledge to create purposeful texts that inform, persuade and engage (ACELY1750

- Identify and analyse implicit or explicit values, beliefs and assumptions in texts and how these are influenced by purposes and likely audiences (ACELY1752

This text set was constructed very differently. Most of the students selected a biography or memoir and were asked to analyse the way the text empowered the reader and how it conveyed meaning about the individual’s life and values. However, there were several students with low literacy and therefore did not have the skills to sufficiently interact with the text in a meaningful manner. The decision was made to curate a booklet with collated extracts from a biography of their choice and supported with additional resources for greater understanding of the text.

Example 3:

The humanities or social studies would greatly benefit from the inclusion of text sets. This is because many expository texts can be very dry and unappealing for the modern student that craves narratives and visualisation (Batchelor, 2017, p.13). As literary learning is already a part of this learning area, teachers are more receptive to utilising text sets as part of pedagogical practices. In particular the inquiry component of the History curriculum scope and sequence allows for the inclusion of information through disciplinary and inquiry sources because they promote critical analysis and evaluation (Lupo et al., 2019, p. 519). Picture book extracts are useful in text sets for History classrooms as they provide meaning through illustrations and imagery. This is especially useful for EALD (English as an additional language or dialect) students and those with low literacy as they are able to use the illustrations to make connections with the content and increase comprehension of the information presented (Batchelor, 2017; NSW DET, (2020).

There is a plethora of literary texts that can be effectively used within text sets. Picture book examples include, Pascoe’s Young Dark Emu (2019), Barbara Knox’s Forbidden City (2006), Gouldthorpe’s The White Mouse (2015), and Zee & Innocenti’s Ericka’s Story (2013), whereas Spiegelman’s Maus (1991) is a fantastic Holocaust source for teenagers about the Holocaust. Other texts of value include Anne Franks’ Diary (1947), Kokoda (2004) by Peter FitzSimons, Simpson and his donkey (2008) by Greenwood, The Rabbits (2008) by Marsden and Pemulway, and The Rainbow Warrior (1988) by Willmot to name a few. Interestingly, Lannin (2020) suggests the use of poetry in text sets as it asks students to look beyond the text and into the imagery that it offers. This means that plays, songs and poems such as Manning’s Close to the bone (1994), Roach’s Took the Children away (1989) and Mackella’s My country (1904) would be useful additions to multidimensional text sets (Lannin et al., 2020).

Contraindications:

Even though there is sufficient information available as to the efficacy of utilising text sets as part of pedagogical practices for a diverse classroom, there are detractors with their concerns. These reluctant teachers feel that there is insufficient time to use literature and literacy strategies due to pressing and continuous assessment (Balkus, 2019, p.25). But their fears are misplaced. Students are still able to gain content knowledge from literary sources and at the same time, bolster their own literacy abilities and cognitive processes (Derewianka, 2015; Balkus, 2019, p.25).

Conclusion:

The inclusion of text sets has many benefits within a diverse classroom. It utilises a compilation of resources to heighten background knowledge, improve student engagement, ameliorate literacy and increase textual comprehension (Lewis & Strong, 2020, p.41). Whilst the benefits are easily visible with text diversity, the greatest educational benefit arises from the explicit instruction of literacy strategies whilst using the text sets in a student centred manner (Lewis & Strong, 2020, p.41; Lupo et al., 2019, p.520). This shows that text sets can be effectively administered and utilised across the curriculum to effectively teach content and bolster literacy and improve learning outcomes.

REFERENCES:

Balkus, Brenna C. (2019). Utilizing Text Sets To Teach Critical Literacy: Bringing Literacy Into The Social Studies Middle School Classroom. School of Education Student Capstone Projects. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.hamline.edu/hse_cp/309

Batchelor, K. E. (2017). Around the world in 80 picture books: Teaching ancient civilizations through text sets. Middle School Journal, 48(1), 13–26. https://doi-org.ezproxy.csu.edu.au/10.1080/00940771.2017.1243922

Beck, P. (2014). Multigenre Text Set Integration: Motivating Reluctant Readers Through Successful Experiences with Text. Journal of Reading Education, 40(1), 12–19. CSU Library.

Cervetti, G.N., & Hiebert, E.H. (2019). Knowledge at the center of English language arts instruction. The Reading Teacher, 72(4), 499–507. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1758

Creighton, J. (6th February, 2014). Isaac Asimov: Science fact and science fiction. Futurism. https://futurism.com/isaac-asimov-science-fact-and-science-fiction

Derewianka, B. (2015). The contribution of genre theory to literacy education in Australia. In J. Turbill, G. Barton & C. Brock (Eds.), Teaching Writing in Today’s Classrooms: Looking back to looking forward (pp. 69-86). Norwood, Australia: Australian Literary Educators’ Association. Retrieved from https://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2620&context=sspapers

Elish-Piper, L., Wold, L., & Schwingendorf, K. (2014). Scaffolding High School Students’ Reading of Complex Texts Using Linked Text Sets. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 57 (7). DOI: 10.1002/jaal.292 © 2014 International Reading Association (pp. 565–574). CSU Library

Hoch, M., McCarty, R., Gurvitz, D. & Sitkoski, I. (2019). Five key principles: guided inquiry with multimodal text sets. The Reading Teacher 72 (6) pp701-710. International Reading Association CSU Library.

Howell, H. (2016). Embedded nonfiction ideas for Macbeth. Teach like a champion [Blog]. Retrieved from https://teachlikeachampion.com/blog/helen-howell-shares-embedded-nonfiction-ideas-macbeth/

Kay, J. (23rd February, 2012). Prophets of science fiction: Jules Verne Recap. ScienceFiction.com. https://sciencefiction.com/2012/02/23/prophets-of-science-fiction-jules-verne-recap/

Lannin, A., Juergensen, R., Smith, C., Van Garderen, D., Folk, W., Palmer, T., & Pinkston, L. (2020). Multimodal text sets to use literature and engage all learners in the science classroom. Science Scope, 44(2), 20–28.

Lewis, W., & Strong, J. (2020). Chapter 3 – Designing content area text sets. In Literacy Instruction with Disciplinary Texts: Strategies for Grades 6-12. Guildford Publications. CSU Library.

Lupo, S., Berry, A., Thacker, E., Sawyer, A., & Merritt, J. (2019). Rethinking text sets to support knowledge building and interdisciplinary learning. International Literacy Association 73 (4). Pp. 513-524. CSU Library. DOI:10.1002/trtr.1869

Lupo, S., Strong, J., Lewis, W., Walpole, S., & McKenna, M. (2017). Building background through reading; Rethinking text sets. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy 61(4), p.433-444. https://doi-org.ezproxy.csu.edu.au/10.1002/jaal.701

Pennington, L. K., & Tackett, M. E. (2021). Using Text Sets to Teach Elementary Learners about Japanese-American Incarceration. Ohio Social Studies Review, 57(1), 1–14.

Mania, K., Mabin, L.K., & Liebenberg, J. (2018). ‘To go boldly’: teaching science fiction to first-year engineering students in a South African context. Cambridge Journal of Education 48 (3), pp389–410, https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2017.1337721

NSW Department of Education. (2020). Planning EAL/D support. Multicultural Education. https://education.nsw.gov.au/teaching-and-learning/curriculum/multicultural-education/english-as-an-additional-language-or-dialect/planning-eald-support

Parker, G. (2018). The top 20 scientific breakthroughs in history. MoneyInc.com. https://moneyinc.com/top-20-scientific-breakthroughs-history/