The leadership and management of a school is heavily dependent on the organisation’s structure and learning culture.

Small businesses, large corporations and government agencies tend to have an organisational structure that is easily identifiable. However, schools and other learning institutions rarely adhere to a single framework and are often a medley of theories and are also heavily influenced by external political, social and economic factors. This variance in organisational framework and external influences can affect the way schools are managed and overall success achieved.

Buijs (2005) argues that the way education and teaching is viewed has a direct influence on teaching practices. Consequently, if education and learning institutions are to be viewed as centres of learning, then the focus of that organisation should be based upon pedagogical practices and the achievement of learning outcomes. Kools & Stoll (2016) elaborate upon this idea further by suggesting that schools are knowledge based organisations with community as a central focus. This is because learning and learning outcomes are exponentially increased when students are emotionally supported in the presence of strong relationships. Consequently the definition of schools as knowledge based learning organisations is more suitable as there is a shared focus on good pedagogical practice, student welfare and a strong emphasis on meaningful relationships. This means schools will have different organisational needs and require a very different leadership style. It is also important to remember that schools are not businesses and cannot be run for a profit from an ethical or moral point of view (Kools & Stoll, 2016).

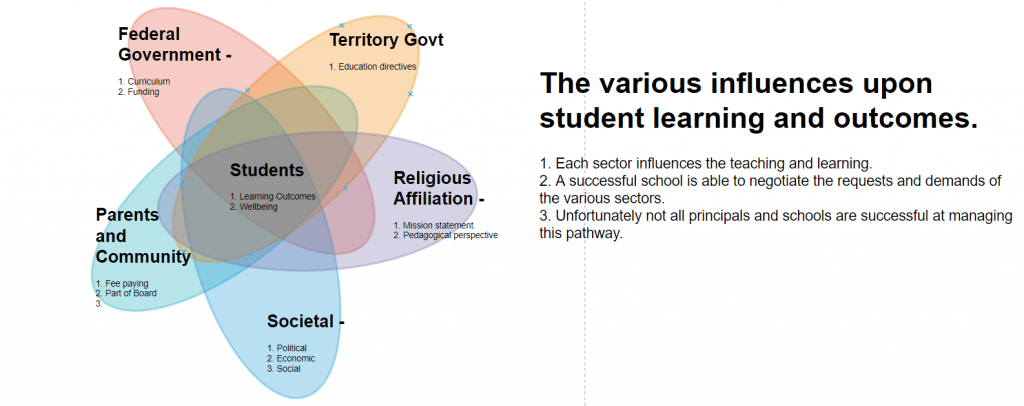

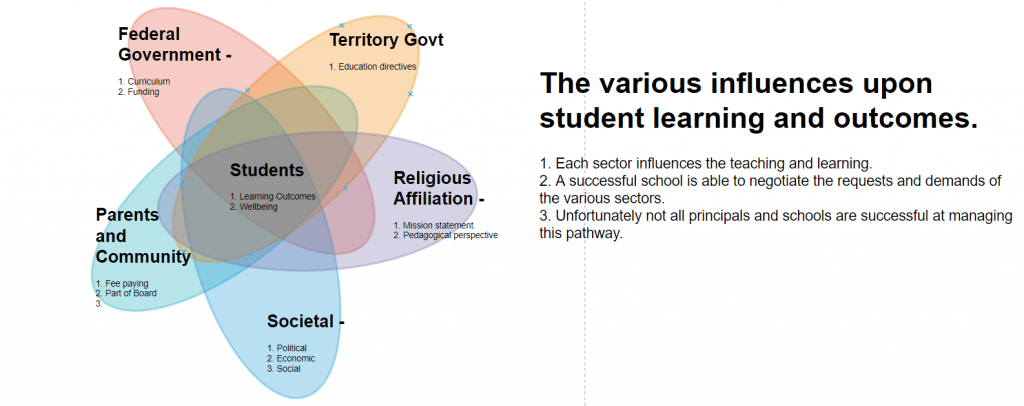

The reality is that most local schools are part of larger organisations, such as education departments or charters, and or have strong links to religious affliliations. This means that as part of larger conglomerates, they are not an independent organisation but are at the behest of the policies and procedures of the parent. This acknowledgement of a parent organisation confirms the presence of machine theory, which can make some schools inefficient and rigid because they are unable to meet the local community due to the largely bureaucratic nature of the overarching organisation. This can be fairly common in education department schools that have to follow a central path instead of meeting the needs of their local community.

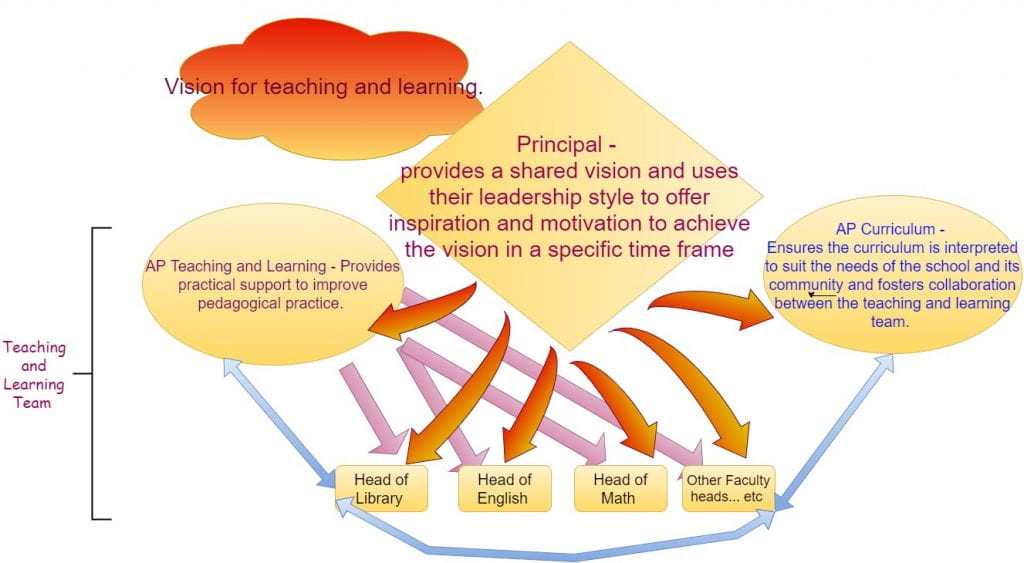

Besides the presence of the overarching machine theory, most individual schools are aligned along the classic management format with a clearly defined hierarchy of authority emanating from the principalship down to heads of faculty, team leaders and then classroom teachers (Kokemuller, 2017). This structure is generally very stable as there are distinct channels of communication and in most circumstances staff are compliant as this system is often replicated across schools and sectors (Kokemuller, 2017).

Interestingly, few schools adhere to the professional organisational theory even though the teachers are considered to be highly educated and thus should have volition of their professional practice. This difference could be due to the difference in how teachers view their own organisation and the way the organisation views teachers. Classroom teachers view their profession as a student centred and have learning outcomes at the focus of their practice. But as schools are often viewed as public property, the actions and decisions made by school leaders are often influenced by the politics and society. The presence of national curriculums, state syllabi, standardised testing and performance reviews limit the professional autonomy of practice teachers truly have. These decisions, such as standardised testing, are often used to measure the efficacy of teachers and schools rather than determining and then resolving inequity between students (Berry, 2018). It also puts into focus the trust and level of professional courtesy extended to teachers themselves by the governing authority and the greater community.

What influences a school’s decision making?

What influences a school’s decision making?

Whilst schools place a system of caring as its focus is beneficial to students, there are some negatives for teachers. Kools & Stool (2017) argue that using vision and purpose to bind workers to an organisation is not always in the worker’s best interests as it puts the organisation’s vision above the needs of the employee. Consistently putting the needs of the organisation above the worker can quickly lead to employee dissatisfaction, reduction in morale and increased attrition rates. This is glaringly obvious when considering the high attrition of teaching staff due to disillusionment and a lack of support (Stroud, 2017). Currently, it is touted that over half of people who hold a teaching degree do not currently work in education and almost a fifth of new graduates do not even register as teachers upon completion of their degree (Stroud, 2017). These statistics do not bode well for schools as learning organisations in the long term. Schools are learning organisations and should be focused on the needs of their learning community and the relationships that support that learning for staff and students.

The unfortunate truth is that the education sector is at the behest of public funds and as such are dependent on governmental policies as well as societal expectations. This means that till there is a consensus about what the actual focus is of schools and other educational institutions, there will continue to be uncertainty about its outcomes, and for the people that work within the system.

The OECD’s report about schools being a learning organisation acknowledges that student learning needs to be the focus of educational institutions (OECD, 2016). It points out that as a learning organisation, schools need to have the flexibility to adapt quickly to changing circumstances, as well as having the internal frameworks to embrace emerging technologies and innovative practice (OECD, 2016). It is evidently clear that for students to receive the necessary skills and knowledge required for the 21st century, schools need to have a shared and collaborative approach to learning. As such, there is a clear need for schools to have a shared vision, a positive culture of learning, support professional development and collaboration, and be able to exchange information freely with the external environment (OECD, 2016, p.1). This type of organisation values its staff members as professionals, and places importance in building those valuable relationships.

Schools are indeed organisations that promote learning and need to have a strong focus on their learning community which includes staff and students. Unfortunately, education sectors are at the behest of public funds and as such are dependent on governmental policies as well as societal expectations. This means that till there is a consensus about what the actual focus is of schools and other educational institutions, there will continue to be uncertainty about its outcomes, and the people that embedded within the system.

References:

Buijs, J. (2005). Teaching: Profession or vocation? Catholic Education: A Journal of Inquiry and Practice, 8; 3. Pp 326-345. Retrieved from https://ejournals.bc.edu/index.php/cej/article/view/590/579

Berry, Y. (March 20, 2018). Time to drop NAPLAN? We shouldn’t treat school like a competition. The Canberra Times. Retrieved from https://www.canberratimes.com.au/story/6021749/time-to-drop-naplan-we-shouldnt-treat-school-like-a-competition/digital-subscription/

Kokemuller, N. (2017). Mintzberg’s five types of organizational structure. Hearst Newspapers: Small business. http://smallbusiness.chron.com/mintzbergs-five-types-organizational-structure-60119.html

Kools, M. and Stoll L. (2016), “What Makes a School a Learning Organisation?”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 137, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jlwm62b3bvh-en

Laming, M.M. and Horne, M. (2013) Career change teachers: Pragmatic choice or a vocation postponed? Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 19 (3). pp. 326-343.

OECD. (2016). What makes a school a learning organisation? A guide for policy makers, school leaders and teachers. UNICEF – Office of Research-Innocenti. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/education/school/school-learning-organisation.pdf

Stroud, G. (2017). Why do teachers leave? ABC News – Opinion. Retrieved from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-02-04/why-do-teachers-leave/8234054

What influences a school’s decision making?

What influences a school’s decision making?