This resources was assessed using the guidelines set out by this RUBRIC

| Citation:

Templeton, T. (2020). White Australia Policy [Sway].

|

|||

| General Selection Criteria: | Digital Literature Selection Criteria: | ||

| Teaching and Learning Needs | 50/50 | Learning, literacy and language development: | 45/50 |

| Curriculum Needs | 20/20 | Format enhances the learning: | 15/20 |

| School Needs: | 20/20 | Features enhance the learning: | 20/20 |

| C/W School Ethos. | 8/10 | Price: | Free 10/10 |

Summary:

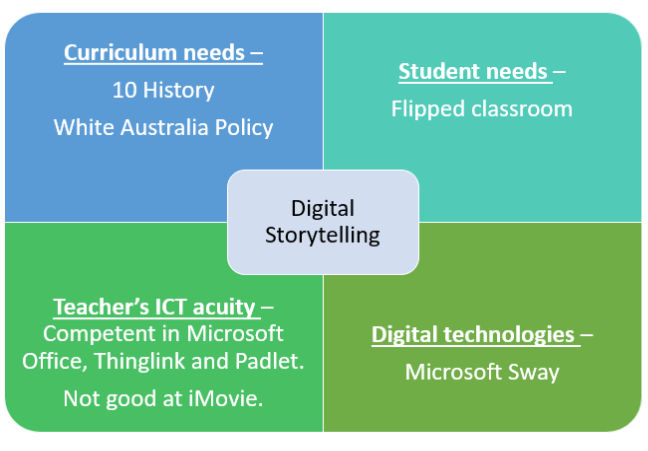

The White Australia Policy [sway] is an internally created teacher resource for use in conjunction with a flipped classroom setting. Designed as the pre-lesson task for the Year 9/10 History – “From Federation to Bicentennial”, this digital narrative contains a variety of primary sources, news clippings, videos, radio interviews and infographics about the different local and global perspectives surrounding the White Australia Policy. The resource is a valuable teaching tool but needs to be accompanied by a teacher facilitated class discussion in order to gain optimum values.

| Curriculum links: | |

| 9/10 History – | Senior History –

ACHMH123 & ACHMH125 (Senior Modern History – Unit 3) ACHMH194 & ACHMH195 (Senior Modern History – Unit 4) |

Learning, Literacy and Language:

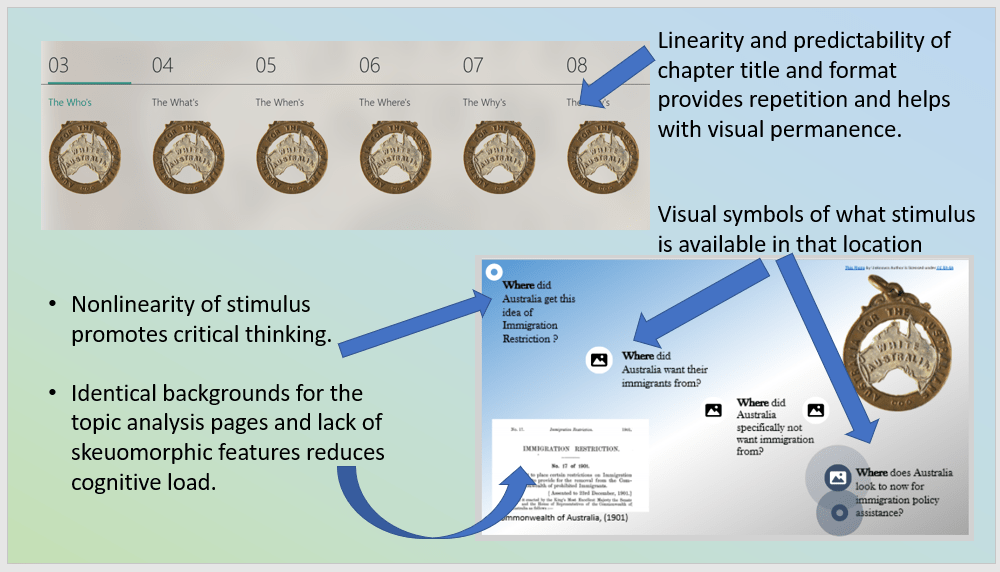

The White Australia Policy [Sway] is a linear interactive digital narrative that has two main purposes. The overt purpose is to assist students through the various perspectives of Australian and world history to understand the reasoning behind the legislation and implementation of this Policy. The variance in viewpoints allow the students to develop their own conclusion about this historical event using the range of primary and secondary sources (Lamb, 2011). The covert purpose of this narrative is to facilitate literacy development by promoting literacy, academic writing and critical thinking.

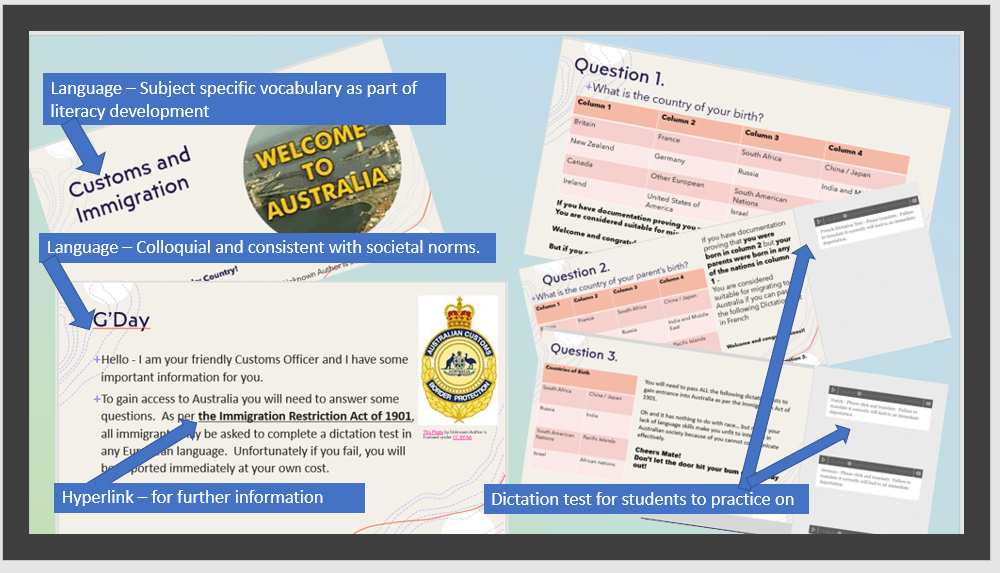

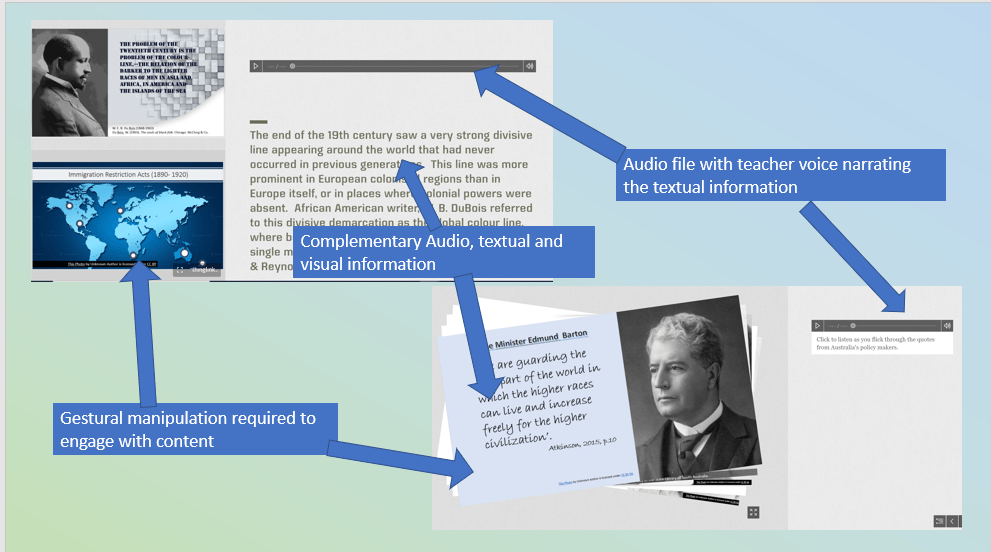

The narrative facilitates literacy development by the use of complementing images, audio and textual elements, and the integration of the teacher as narrator is a direct attempt to use prior rapport to connect the students to the content (Ibrahim, 2012; Mangen et al., 2013). This congruence of information is more effective at promoting knowledge and comprehension as the complementing audio and textual elements allow the student to experience the benefits of a read aloud in the privacy of their own home (Rhodes, 2019; Ibrahim, 2012). Whilst the language used within the resource is diverse and subject specific, it may be difficult for students with learning or developmental needs to process, and thus it would have been beneficial to have hyperlinks available to assist with comprehension (Fitzsimmons, Weal & Drieghe, 2019).

The narrative facilitates literacy development by the use of complementing images, audio and textual elements, and the integration of the teacher as narrator is a direct attempt to use prior rapport to connect the students to the content (Ibrahim, 2012; Mangen et al., 2013). This congruence of information is more effective at promoting knowledge and comprehension as the complementing audio and textual elements allow the student to experience the benefits of a read aloud in the privacy of their own home (Rhodes, 2019; Ibrahim, 2012). Whilst the language used within the resource is diverse and subject specific, it may be difficult for students with learning or developmental needs to process, and thus it would have been beneficial to have hyperlinks available to assist with comprehension (Fitzsimmons, Weal & Drieghe, 2019).

The Sway’s textual elements with its formal tone, in text citations and use of subject specific vocabulary were designed to provide an archetype of academic writing (Cutler, 2019). Literacy Toolkit (2019) recommends the use of modelled writing as an explicit teaching strategy to address elements of writing such as sequence, linking ideas and vocabulary choice. It allows students who lack confidence in their writing to learn strategies and techniques that they can use in their own writing (Literacy Toolkit, 2019). It also allows those students who lack familiarity with in text citations to experience how citations are intext and referenced.

Digital narratives like this Sway combines emerging technology and literary works in a manner that improves critical thinking and 21st century literacies (Moran et al., 2020; Ciccorico, 2012). As students navigate through the various modalities, they experience a variety of primary sources that would be viewed as discriminatory in modern Australia. The blatant racial stereotyping evident in some of the primary sources may cause some students distress. This transmedia resource will challenge student’s perceptions of Australian history, as well as develop their critical thinking and digital literacies (Kopka, 2014).

Technology trends.

Ross Johnston (2014) and Leu et al., (2015) point out that the inclusion of interactive digital literature into educational practices meets the modern societal paradigm and allows students to develop valuable 21st century skills. The use of transmedia sources such as this Sway would benefit students by developing their critical thinking, experiential learning and their digital literacy (Cullen, 2015; Pietschmann, Volker & Ohler, 2014; Kopka, 2014; Leu et al., 2015).

Resource Integration:

The White Australia Policy [sway] is a teacher created digital narrative and is freely available on the school intranet with no licensing limitations making it a very thrifty resource. It can be integrated into the library management system, class intranet pages and into any of the Microsoft office suite. It is also accessible from all personal devices and can be exported to Word and printed out for students who are disadvantaged by the digital divide (DIIS, 2016).

Recommendation:

The White Australia Policy [sway] would be a valuable addition to the school collection.

References:

Cullen, M. (2015, December 21). How is interactive media changing the way children learn. In EducationTechnology. Retrieved from https://educationtechnologysolutions.com.au/2015/12/how-is-interactive-media-changing-the-way-children-learn/

Cutler, D. (2019). Modeling writing and revising for students. Edutopia. Retrieved from https://www.edutopia.org/article/modeling-writing-and-revising-students

Department of Industry, Innovation and Science. (2016). Australia’s digital economy update. Retrieved from https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2016/05/apo-nid66202-1210631.pdf

Fitzsimmons, G., Weal, M., & Drieghe, D. (2019). The impact of hyperlinks on reading text. PLOS ONE. Retrieved from https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0210900

Ibrahim, M. (2012). Implications of designing instructional video using cognitive theory of multimedia learning. Critical Questions in Education 3(2), p.83-104. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1047003

Kopka, S. & Hobbs, R., (2014). Transmedia & Education: Using Transmedia in the Classroom with a Focus on Interactive Literature [Blog]. SeKopka. Retrieved from https://sekopka.wordpress.com/2014/05/07/transmedia-education-using-transmedia-in-the-classroom-with-a-focus-on-interactive-literature/

Lamb, A. (2011). Reading re-defined for a transmedia universe. Learning & Leading with Technology 39(3), p.12-17. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ954320

Leu, D.J, Forzani, E., Timbrell, N., & Maykel., C. (2015) . Seeing the forest, not the trees: Essential technologies for literacy in primary grade and upper elementary grade classroom. Reading Teacher 69: (2), p.139-145. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1073399.

Literacy Teaching Toolkit. (2019). Modelled writing. Victorian Department of Education. Retrieved from https://www.education.vic.gov.au/school/teachers/teachingresources/discipline/english/literacy/writing/Pages/teachingpracmodelled.aspx

Mangen, A., Walgermo, B. R. & Bronnick, K.A. (2013). Reading linear texts on paper versus computer screen: Effects on reading comprehension. International Journal of Educational Research, 58, 61-68.doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2012.12.002

Pietschmann, D., Volkel, S., & Ohler, P. (2014). Limitations of transmedia storytelling for children: A cognitive development analysis. International Journal of Communication 8, p.2259-2282. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279323387_Limitations_of_Transmedia_Storytelling_for_Children_A_Cognitive_Developmental_Analysis

Rhodes, G. (2019). Why I read aloud to my teenagers. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2019/feb/09/why-i-read-aloud-to-my-teenagers

Ross Johnston, R. (2014a). Chapter 23 – Literature, the curriculum and 21st-century literacy. In G. Winch, R. Ross Johnston, P. March, L. Ljungdahl & M. Holliday (Eds.), Literacy: Reading, writing and children’s literature (5th ed., pp. 472-489). Melbourne: Oxford University Press.