Creating a digital narrative requires planning.

Creating a digital narrative for classroom practice requires extensive planning.

Creating a digital narrative for a university assignment that can also be used for classroom practice turns a teetotaler into a wino.

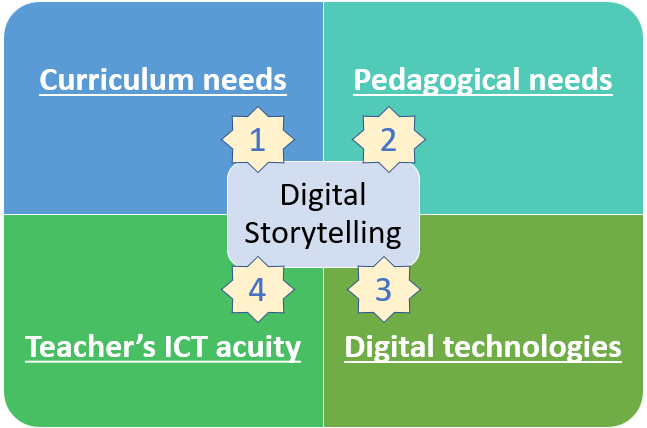

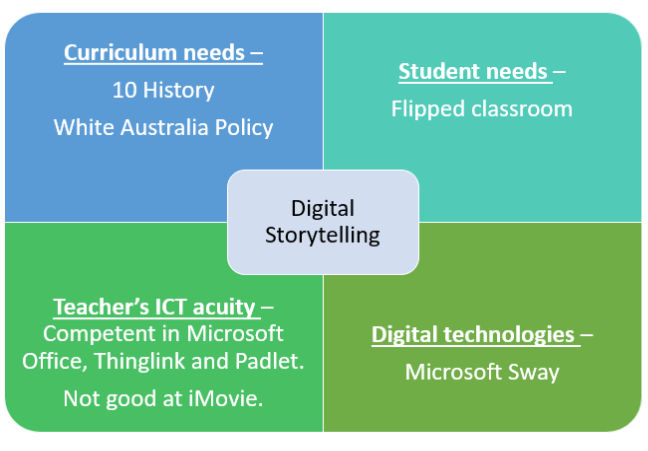

The creation of a digital narrative (DN) for education practice requires the teacher to consider the curriculum content, the needs of the student, the digital technologies available and their own individual ICT acuity.

- A clear understanding of which parts of the curriculum need to be addressed, content or skills (or both)

- The cognitive, behavioural and developmental needs of the students.

- The technological capabilities of the school such as BYOD policies and wifi capabilities.

- It also requires the educator to acknowledge their own capability and find ways to work within their capacity. This last fact is often crucial as many teachers feel that creation of interactive media is beyond their capability and therefore abstain from using DST in classroom practice (Hyndman, 2018).

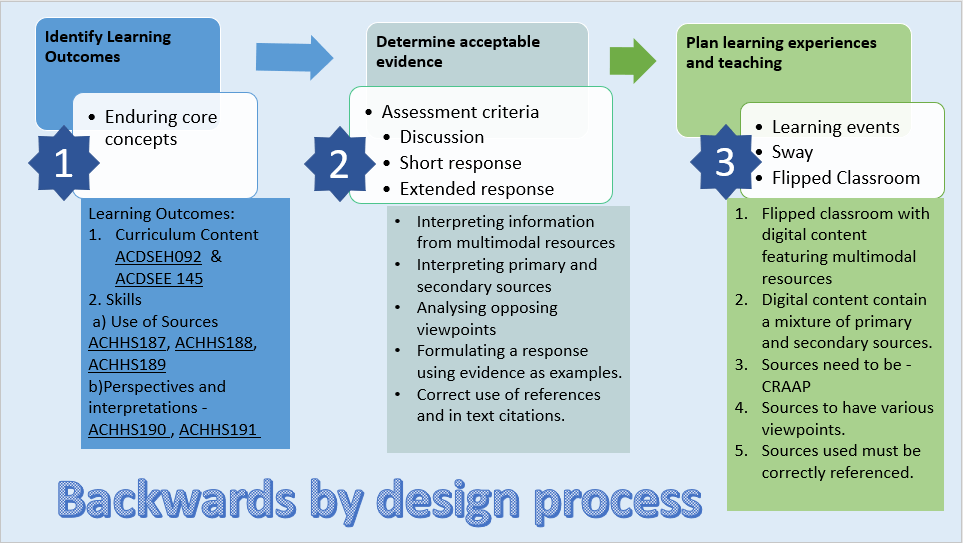

Whilst there are many pedagogical strategies in which an educator can introduce DN or DST into classroom practice, the most effective method for teacher librarians to use is the Backwards Design Process (BPD), or otherwise known as backwards by design. BPD can be utilised across all areas of the curriculum and is often used by teacher librarians as a method of developing information literacy lessons (Gooudzward, 2019). Therefore it seemed like the sensible way to create this DN due to my familiarity with the process.

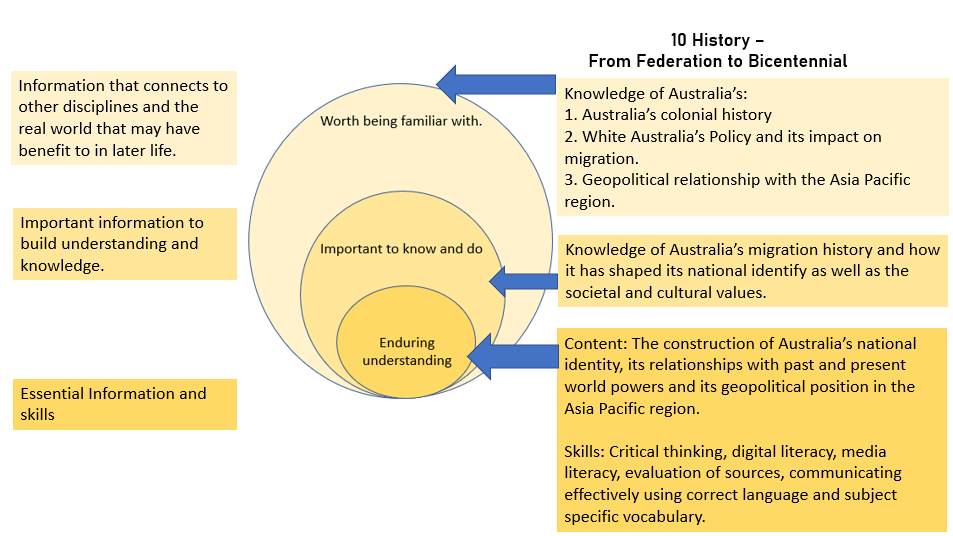

- The identification of the learning outcomes in both content and skills strands of the 10 History curriculum (ACARA, 2014).

- Once the learning outcomes were identified, the method and process of evaluating these learning outcomes needed to be determined.

- Kurt (2018) and Gooudzward (2019) both point out the importance of ‘ranking’ the outcomes and then correlating them to the complexity of the assessment. The use of Bloom’s taxonomy would be useful here to help differentiate the learning.

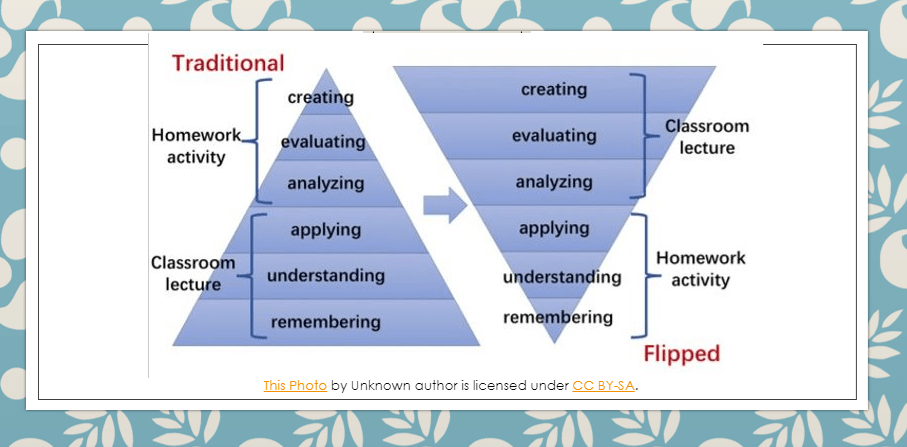

- Now the learning events can be planned. Considerations should include the type of learning that would suit this unit such as blended learning, explicit instruction, inquiry learning or the use of flipped classroom.

Part B – Student Needs – Pedagogy that works.

When creating or using DST, acknowledging the needs of the students is a fundamental part of pedagogical practice. The White Australia Policy was a very inflammatory legislation and requires finesse and discretion when addressing it in a classroom setting. Students who are recent immigrants or those that were descendants of those restricted by the White Australia Policy may need time and space to process this information. The use of a flipped classroom as a pedagogical strategy allows for the embedding of a DST for students to access prior to the lesson (Schmidt & Ralph, 2016, p.1). This gives the student time and space to process the information privately and the integrated questions promote critical thinking. This strategy also promotes analysis and evaluation of the policy as well as time for the teacher to facilitate class discussion and address the needs of a diverse classroom (Basal, 2015).

Part C: Technological capacities.

Part C: Technological capacities.

The use of Microsoft Sway was based on expediency. My school has a subscription to Microsoft and the students have already engaged with the program in other disciplines. The format allows for the successful integration of images, videos, audio, hyperlinks and Thinglink. It can be accessed from any personal device connected to the internet, is intuitive to use and can be successfully integrated into the school intranet, class pages and can be cataloged into the library management system.

The school has a BYOD policy and excellent wifi, so there should be minimal issues accessing this resource.

Part D: Teacher Competence

Cantabrana et al., (2018) point out that the quality of education in the 21st century is directly linked to teacher education and training. Teachers that have been supported in their professional learning and development to integrate DL into their practice are more likely to use it successfully (Cantabrana et al., 2018). Competence in ICT involves positive attitudes to technology as well as combing conceptual and procedural knowledge (Cantabrana et al., 2018, p.77; McGarr & McDonagh, 2019, p.11). This means that teachers that are reluctant to use ICT from either lack of knowledge or lack of interest are less likely to want to improve their capability and extremely unlikely to create and foster the use of DL and DST in their classroom practice.

McGarr & McDonagh (2019) point out that teacher competence should be framed around three main areas, technological, cognitive and ethical. This makes sense as creating a digital narrative requires the teacher to be competent at combining curriculum with technology, whilst ensuring copyright is addressed appropriately (McGarr & McDonagh, 2019, p.13).

References:

ACARA. (2014b). HASS – History Curriculum. F-10 Curriculum. Educational Services Australia. Retrieved from https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/humanities-and-social-sciences/history/

Basal, A. (2015). The implementation of a flipped classroom in foreign language teaching. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education 16 (4). DOI:: 10.17718/tojde.72185

Cantabrana, JL., Rodriguez, M., & Cervera, M.G. (2018). Assessing teacher digital competence: the construction of an instrument for measuring the knowledge of pre-service teachers. Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research. 8(1), p73-78. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1202957.pdf

Goudzwaard, M. (2019). Slides: Backward design for librarians. New England Library Instruction Group 2. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1052&context=nelig

Hyndman, B. (2018). Ten reasons teachers can struggle to use technology in the classroom. The Conversation [Blog]. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/ten-reasons-teachers-can-struggle-to-use-technology-in-the-classroom-101114

Kurt, S. (2018). What is backward design. Educational Technology. Teaching and Learning Resources. Retrieved from https://educationaltechnology.net/backward-design-understanding-by-design/

McGarr, O., & McDonagh, A. (2019). Digital competence in teacher education. Output 1 of the Erasmus+ funded Developing Student Teachers’ Digital Competence (DICTE) project. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331487411_Digital_Competence_in_Teacher_Education

Schmidt, S. & Ralph, D. (2016). The flipped classroom: a twist on teaching. Contemporary Issues in Education Research. 9(1). Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1087603.pdf