THE THINKING

Citation:

Templeton, T. (2020). White Australia Policy [Sway]. Daramalan College Teacher Resources. Daramalan College Library. Canberra.

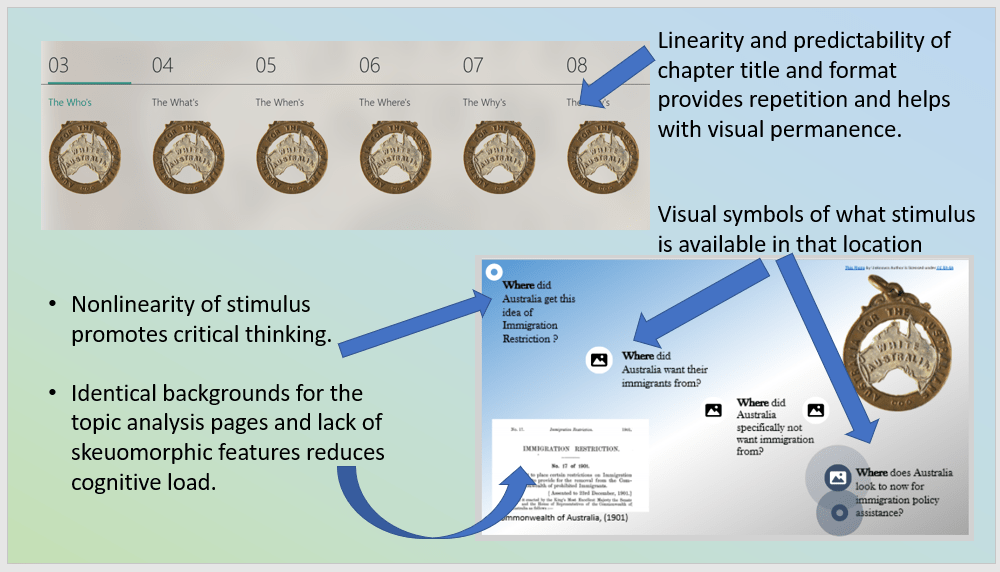

The Immigration Restriction Act of 1901 was one of the first pieces of legislation created by the newly formed Australian Federal Government and is the main focus of this digital narrative (DN). Commonly referred to as the White Australia Policy (WAP), the Act was designed to maintain racial homogeneity and the economic value of the Australian man (Fong, 2018). Whilst the Act is addressed in Year 10 History and Senior Modern History, the cognitive and curriculum focus of this DST is aimed at the 9/10 History Unit of work – Australia – From Federation to the Bicentennial (ACARA, 2014a; ACARA; 2014b). The utilisation of a multimodal DN in a flipped classroom (FC) dynamic was a strategic ploy to encourage student ownership of learning, approach sensitive content suitably, promote collegial discussion, and allow the teacher to meet the needs of a diverse classroom (Gonzales, 2016; Schmidt and Ralph, 2016, p.1).

Pedagogy

Digital storytelling (DST) is an emerging pedagogical practice that effectively combines technology and literary work for use in recreational, personal or educational endeavours (Ciccorico, 2012; Ohler, 2013, p.94). It is the modern adaptation of oral traditions, and the use of the narrative structure promotes reflective processes whilst communicating content in a manner that meets the cognitive, behavioural and developmental needs of students (Vidales-Bolanos and Sadaba-Chalezquer, 2017). DST promotes Information Communication Technology (ICT) acuity, competency in digital literacies and a participatory culture, as it encourages students to move beyond passive consumption and into interacting and creating with it (Leu et al., 2011; Hashim and Vongkulluksn, 2018).

A DN created with Microsoft Sway allows students to interact with the different literacies and interactive elements, furthering valuable 21st century skills and improving the quality of transactions between the narrative and the reader (Ciccorico, 2012; Moran et al., 2020). The format allows for the successful integration of visual and audio resources, and the use of personal devices increases teen engagement because technology is intrinsically linked to a teen’s social capital (Moran et al., 2020, p.6; Vidales-Bolanos and Sadaba-Chalezquer, 2017).

Classroom Context

Flipped classrooms (FC) are a transformative student centred teaching strategy with two distinct components, an external technology-based component followed by an interactive section (Ozdamli and Asiksoy, 2016, p.99; Schmidt and Ralph, 2016, p1.). This inverted learning sequence allows students to gain access to the content prior to the lesson, which then allows for the teacher to facilitate discussion and meet the varying needs of the students (Basal, 2015; Schmidt and Ralph, 2016, p.1). Implementing FC also allows student learning and engagement to be observed, documented and any misconceptions clarified (Leask, 2014). As Schmidt & Ralph (2006, p.1) point out, guided discussion is essential for all students but especially for low literacy and ability students. FC are constructivist in nature, self-paced, promote student ownership of learning and build critical study skills which are essential for lifelong learning (Basal, 2015).

Digital Technologies

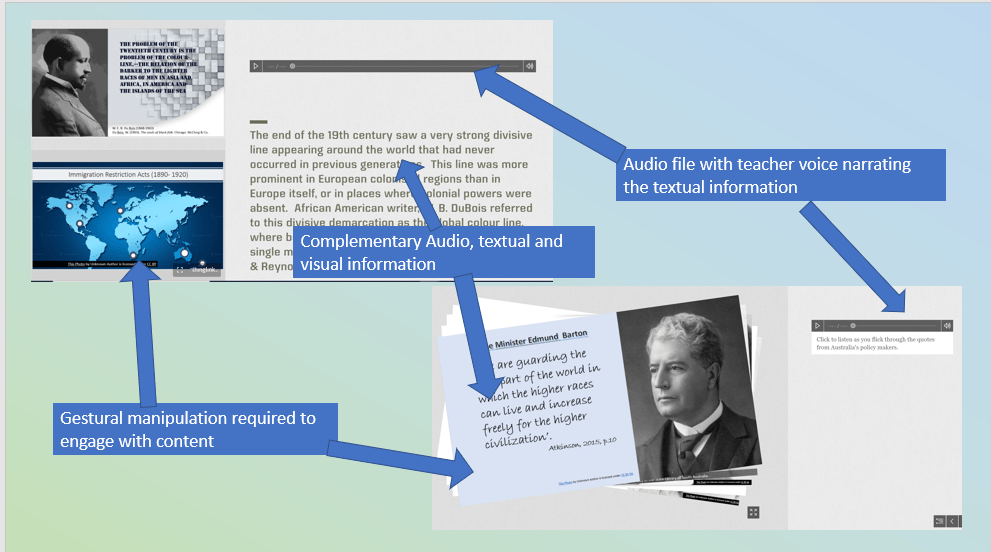

Digital technologies and multimodal resources (MR) are an integral aspect of DN and other modern classroom pedagogies (Ibrahim, 2020). MR can be static, such as picture books and graphic novels, or dynamic such as Sway, Powerpoint, Thinglink, digital textbooks, and interactive websites (Ibrahim, 2020). This DN utilises Sway and Thinglink because the software programs embed together well, and their combined interactivity promotes engagement as well as encourage gestural manipulation to access information (Ibrahim, 2012; Heick, 2017).

The resources themselves do not espouse learning. Instead it is the juxtaposition of media which conveys information at the correct level and the subsequent class discussion that has the greatest impact on student learning (Mayer and Morena, 2005; Ibrahim, 2012). When multimodal information complement and enhance each other, the brain is able to decode, deduce, categorise and construct this new information efficiently upon prior knowledge and thereby reducing the cognitive load (Mayer and Morena, 2005; Ibrahim 2012; David, 2020). But when the varying forms of media have less than optimum layout and delivery, the brain becomes overloaded and processing time increases leading to an increased cognitive load leading to lower comprehension and failure to make meaning (David, 2020). Therefore, it is important that DN created for use in a classroom setting utilise the multimedia principles to ensure cognitive load is maintained for optimum intellectual performance (Ibrahim, 2012; Heick, 2017).

School Context – Students:

Daramalan College is a culturally diverse co-educational high school with many students’ descendants of the post war immigration schemes (ABS, 2016). Therefore, discretion and finesse are required when addressing outdated perceptions of race and ethnic diversity. The utilisation of a DST in a FC allows the student to process the information privately and then engage in discussion to develop further understanding.

School Context – Technology:

Sway was selected due to its inclusion in the school’s subscription to Microsoft Office and that it can be successfully catalogued into the library management system. This meets the requirements dictated by the school’s Collection Management and Development Policy. Other benefits include its intuitiveness, ease of use and ability to integrate multimodal resources.

REFERENCES:

ACARA. (2014)a. HASS – History Curriculum. F-10 Curriculum. Educational Services Australia. Retrieved from https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/humanities-and-social-sciences/history/

ACARA. (2014b). Modern History Unit 4 – HASS. Senior Secondary Curriculum. Educational Services Australia. Retrieved from https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/senior-secondary-curriculum/humanities-and-social-sciences/modern-history/

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2016). 2016 Census Quick Stats – Australia Capital Territory (No. 8ACTE). Retrieved from https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/8ACTE?opendocument.

Basal, A. (2015). The implementation of a flipped classroom in foreign language teaching. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education 16 (4). DOI:: 10.17718/tojde.72185

Ciccoricco, D. (2012). Chapter 34 – Digital fiction – networked narratives. In Bray, J., Gibbons, A., & McHale, B. (2012). The Routledge Companion to Experimental Literature. Taylor & Francis eBooks. Retrieved from CSU Library.

Cornet, C. E. (2014). Integrating the literary arts throughout the curriculum. In Creating meaning through literature and the arts: arts integration for Classroom teachers (5th ed,) pp144-193. USA

David, L. (2020). Cognitive theory of multimedia learning (Mayer). Learning Theories. Retrieved from https://www.learning-theories.com/cognitive-theory-of-multimedia-learning-mayer.html

Fong, N. (2018). The significance of the Northern Territory in the formulation of ‘White Australia’s Policies’ 1880-1901. Australian Historical Studies, 49 (4), p.527-545. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1031461X.2018.1515963

Gonzalez, J. (2016). Graphic novels in the classroom. [Blog] Cult of Pedagogy. Retrieved from https://www.cultofpedagogy.com/teaching-graphic-novels/

Hashim, A., & VongKulluskn, V. (2018). E reader apps and reading engagement: A descriptive case study. Computers and Education 125, pp.358-375. Retrieved from https://www.journals.elsevier.com/computers-and-education/

Heick, T. (2017). What is cognitive load theory? A definition for teachers. TeachThought. Retrieved from https://www.teachthought.com/learning/cognitive-load-theory–definition-teachers/

Ibrahim, M. (2012). Implications of designing instructional video using cognitive theory of multimedia learning. Critical Questions in Education 3(2), p.83-104. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1047003

Leask, A. (2014). 5 reasons why the flipped classroom benefits educators. Enable Education – Online learning solutions. Retrieved from https://www.enableeducation.com/5-reasons-why-the-flipped-classroom-benefits-educators/

Leu, D.J., Forzani, E., Timbrell, N., & Maykel, C. (2015). Seeing the forest, not the trees: Essential technologies for literacy in primary grade and upper elementary grade classroom. Reading Teacher 69: (2), p.139-145. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1073399.

Mannheim, M. (2020). Canberra is expanding Australia’s biggest free public WiFi network but how many people use it? ABC News Canberra. Retrieved from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-08-13/canberra-expands-free-wifi-but-fewer-people-are-using-it/12551266

Mayer, R., & Moreno, R. (1998). A Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning: Implications for Design Principles. CHI 1998. DOI:10.1177/1463499606066892

Mayer, R., & Moreno, R. (2005). A cognitive theory of multimedia learning; Implications for design principles. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/248528255_A_Cognitive_Theory_of_Multimedia_Learning_Implications_for_Design_Principles

Moran, R., Lamie, C., Robertson, L., & Tai, C. (2020). Narrative writing, digital storytelling, and coding: Increasing motivation with young readers and writers. Australian Literacy Educators Association, 25 (2), p.6-10. Retrieved from https://primo.csu.edu.au/permalink/61CSU_INST/15aovd3/cdi_gale_infotracacademiconefile_A627277934

NSW Migration Heritage Centre. (2010). Australian migration history timeline – 1945-1965. Powerhouse Museum Collections. Retrieved from http://www.migrationheritage.nsw.gov.au/exhibition/objectsthroughtime-history/1945-1965/index.html

Ohler, J.B. (2013). Digital storytelling in the classroom. New media pathways to literacy, learning, and creativity (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin. Retrieved from https://primo.csu.edu.au/permalink/61CSU_INST/1hkg98a/alma991012780180302357

Ozdamli, F., & Asiksoy, G. (2016). Flipped classroom approach. World Journal on Educational Technology: Current Issues. 8(2), p98-105. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1141886.pdf

Schmidt, S. & Ralph, D. (2016). The flipped classroom: a twist on teaching. Contemporary Issues in Education Research. 9(1). Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1087603.pdf

Vidales-Bolanos, M., & Sadaba-Chalezquer, C. (2017). Connected Teens: Measuring the Impact of Mobile Phones on Social Relationships through Social Capital. Media Education Research Journal 53(25). Retrieved by https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1171085.pdf