Literacies: Pedagogical practice for teacher librarians

Theory of Literacies:

Literacy is an essential skill, but the definition of literacy and a literate person has changed dramatically in the past few decades. Previously, the term literacy was categorised as the decoding and composing of print texts. However, the advent of the information society with its technological advancements, widespread use of personal devices and the pervasiveness of the internet has led to a diversification of format and resulting in the creation of audiovisual, print, digital and multimodal texts (Ferguson, 2019). This heterogeneity of text types means that teachers, schools and the education system need to adapt their pedagogies and practices that encompass the variety of literacies and text types in the modern world (Templeton, 2021a). It also means that the definition of literacy needs to be redefined as the ability to interact with, engage and communicate across modalities for personal, social, economic and recreational purposes (ACARA, 2018)

TL Reality

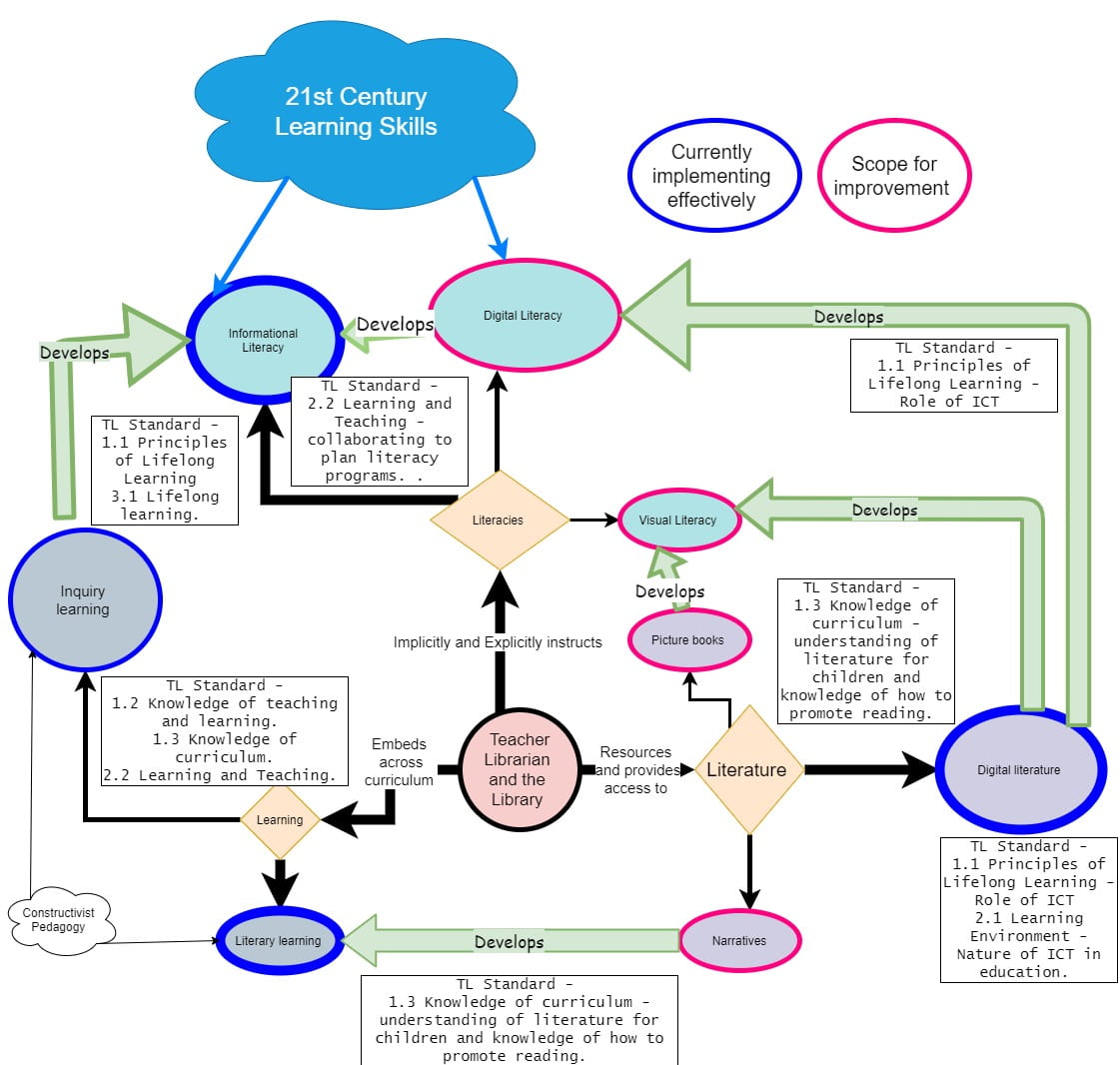

The role of the library and teacher librarian is to support the explicit instruction of multiliteracies and resourcing of multimodal text types in a school as highlighted in ETL401 and ETL504 (ALIA & ASLA, 2004). Whilst print literacy competency is still an essential attribute, the promotion of information, digital and visual literacies are rapidly emerging as essential 21st century skills.

FACT:

Information literacy is the ability of a person to seek, find, access, use and evaluate information successfully for personal, educational and professional purposes (Kaplowitz, 2014; Kong, 2015). It is essential due to the prevalence of mal-information, disinformation and misinformation. This means that in order to navigate these perils of modern society, young people need to be adept at seeking, finding and using information. They also need to be competent at evaluating the difference between gold and dross.

TL REALITY:

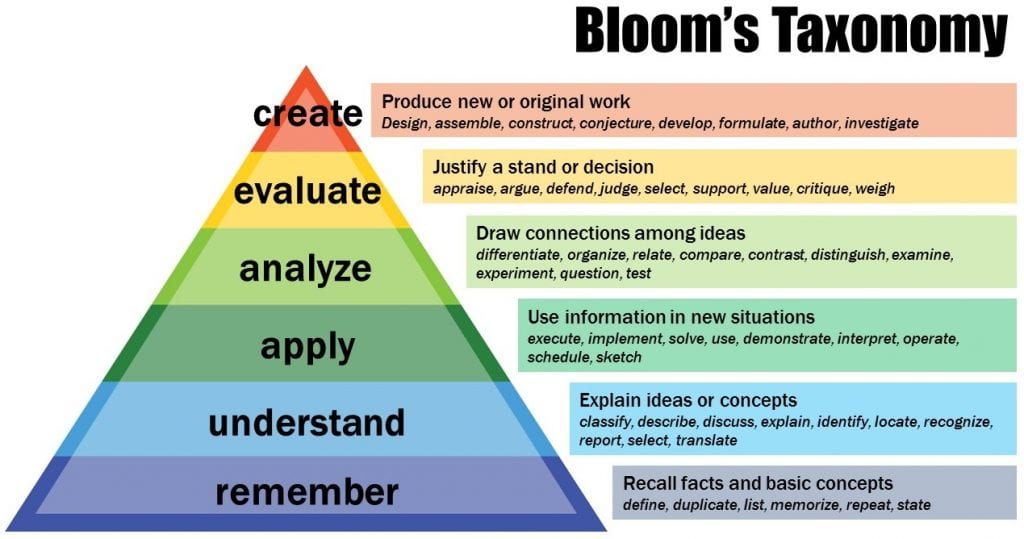

An intrinsic aspect of teacher librarianship is the implementation and embedding of IL skills across the curriculum (Templeton, 2021b). This is because TLs are the traditional gatekeepers of information in schools and have the professional capacity to implicitly and explicitly instruct information literacy to the school community (Levitov, 2016). ETL401 pointed out that inquiry learning or problem based learning is the most effective process at developing information literacy skills because the process is centred upon skill acquisition. However, IL skills need to be integrated and structured incrementally because competency is based upon cumulative access.

MY LEARNING:

IL has always been an essential part of TL practice and the virtual study visits highlighted its importance in Victoria University, William Angliss TAFE and University of Newcastle. These institutions understood their students preferred synchronous sessions and therefore developed an IL framework that allowed this either in person or virtually. Their approach was the motivation for my placement at ACU library because ACU’s Library learning and teaching sessions uses ability as a differentiation tool because their framework supports self navigation, life long learners and independent inquiry.

FACT:

Visual literacy is rapidly becoming an essential skill in a multimodal society because it effectively broadens the parameters of traditional literacy and assists with text deconstruction and analysis, as well as builds competency in language, texts and symbols (Marsh, 2010).

TL REALITY:

Picture books (PB) are effective at developing visual literacy because they can positively impact the academic, behavioural, developmental, cognitive development of learners. This is because PB are polysemic, promote critical thinking, encourage reflection, support constructivist pedagogies and are also excellent tools for class discussion (Marsh, 2010). Their value is in their ability to encourage readers to construct their own meaning from the imagery which then encourages multiple perspectives and creates opportunities for robust discussion (Marsh, 2010).

Picture books for older readers.

Sophisticated picture books.

MY LEARNING:

I was under the false assumption that PB were for young children because developing readers require the interdependency of images and texts for comprehension. However, PB can be effectively used in secondary classrooms through literary learning, read alouds and within classroom practice. This is because post-modern or sophisticated picture books places a higher cognitive load onto the reader and require critical thinking from the reader to decode the contradiction of text and images, or lack of text.

FACT:

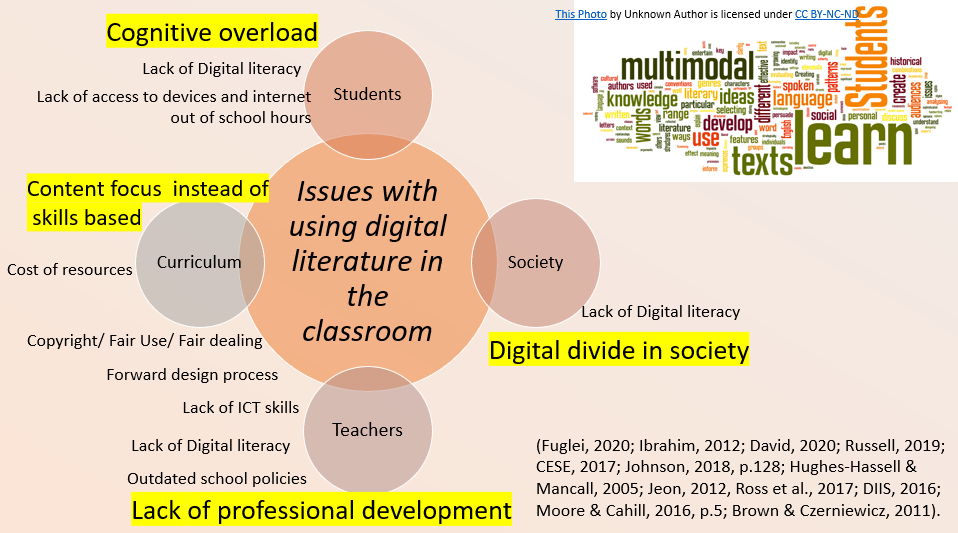

Digital (Multimodal) Literacy is the ability of the user to seek, access, use, integrate and compose digital media for personal, professional, educational and recreational purposes (Lofton, 2016). Technology is constantly evolving and society needs to upskill to stay relevant (Ferguson, 2019). Unfortunately, the digital divide interferes with this ability to upskill, leading to many students and adults lacking the necessary digital literacy skills required in modern society (Thomas et al., 2018). This digital divide is no longer presumed to be due to a generational gap, but rather it is a strong demarcation between people who have regular access to digital technologies and those that do not.

TL REALITY:

An effective method to improve digital literacy in schools is to embed technologies into classroom practice, use explicit instruction to support its implementation and then encourage students to apply their knowledge. It is the intentional use of digital media in pedagogy that then goes on to enhance learning, improve ICT acuity, increase engagement and on a whole, improve learning outcomes. It is not a lecture on powerpoint!

MY LEARNING:

In ETL402 and INF533 I learned about the various strategies to improve digital literacy in the classroom. These included the inclusion of digital texts into classroom practice and innovative pedagogical practices. Some examples of these strategies are:

Digital texts:

Digital pedagogical strategies.

Flipped classrooms are rapidly increasing in popularity, as are augmented and virtual realities because they utilise digital technologies.

Book trailers and book bentos (example below) are audiovisual representations of texts and are useful in promoting literary learning and multimodal literacy.

AR and VR can be effectively used to engage students, for location or inquiry learning, and or for assessment purposes. whereas the article in Magpies Magazine points out how AR can be effectively used in libraries.

Contents of Magpies magazine.

Book Bento Example of – Angela’s Ashes

Click HERE to move to

Part B – Theory into Practice – Learning.

REFERENCES:

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. (2018). Literacy in the Australian curriculum – General capabilities. F-10 Curriculum.

Australian School Library Association & Australian Library and Information Association. (2004). Australian professional standards for teacher librarians. ALIA. https://asla.org.au/resources/Documents/Website%20Documents/Policies/TLstandards.pdf

Department of Industry, Innovation and Science. (2016). Australia’s digital economy update. https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2016/05/apo-nid66202-1210631.pdf

Ferguson, S. (2019). Digital Literacy: A Constantly Evolving Learning Landscape. Alki, 35(2), 12–13. CSU Library

Kaplowitz, J. (2014). Designing information literacy instruction: the teaching tripod approach. Rowman & Littlefield. Ebook. CSU Library.

Kong, S. (2014). Developing information literacy and critical thinking skills through domain knowledge learning in digital classrooms: An experience of practicing flipped classroom strategy. Computers & Education. 78, pp.160-173. DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.05.00

Levitov, D. (2016). School libraries, librarians and inquiry learning. Teacher Librarian 43(4), p.28. CSU Library.

Marsh, D. (2010). The case for picture books in secondary schools. Lianza, 51(4), 27. https://doms.csu.edu.au/csu/file/f7b0a0c2-d0c5-4ba3-8644-6955ea9850b6/1/marsh-d.pdf

Miller, H. (2017). The myth of the digital native generation. E-Learning Inside. https://news.elearninginside.com/myth-digital-native-generation/

Templeton, T. (27 July, 2021a). Digital literacy and the teacher librarian – Part One. Softlink. https://www.softlinkint.com/blog/digital-literacy-and-the-teacher-librarian-part-one/

Templeton, T. (27 July, 2021b). Digital literacy and the teacher librarian – Part Two. Softlink. https://www.softlinkint.com/blog/digital-literacy-and-the-teacher-librarian-part-two/

Thomas, J., Barraket, J., Wilson, C., Cook, K., Louie, Y., Holcombe-James, I., Ewing, S., and MacDonald, T. (2018). Measuring Australia’s Digital Divide: The Australian Digital Inclusion Index 2018. RMIT University, Melbourne, DOI: https://doi.org/10.25916/5b594e4475a00