geralt / Pixabay

Contemporary libraries for the contemporary student

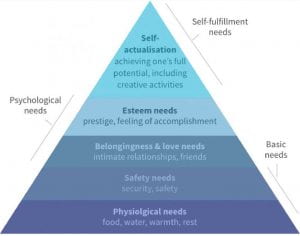

MCEETYA (2008) envisaged the modern student as an engaged learner, literate across modalities and able to critically evaluate the present pervasive overload of information. This contemporary student needs a library that enables these abilities and meets their cognitive, behavioural and developmental needs, so that they can gain an active citizenship in a digital world. Since the primary focus of any school library is to meet the needs of curriculum and the students, a school library Collection Development and Management Policy (CDMP) needs to address these 21st century mandates (ASLA & VCTL, 2018; MCEETYA, 2008; Mitchell, 2011; Learning for the Future, 2001; Nat Lib of NZ, n.d.b).

The robustness of a school library collection is dependent on its CDMP, and consists of physical and electronic resources accessible by the library management system or LMS (Mitchell, 2011, p.10). Physical resources include books, maps, atlases, CDs, DVDs, and the various technologies required to gain access to them (ASLA & VCTL, 2018, p.10). Electronic resources include digital literature, ebooks, audiobooks, online encyclopaedias and useful websites as well as devices such as e-readers, laptops and tablets (ASLA & VCTL, 2018, p.10). To be considered as part of the collection and included within the LMS, resources need to be curated against a set of selection criteria to ensure that they meet curriculum outcomes (ASLA & VCTL, 2018; Mitchell, 2011, p.10; Johnson, 2018). Unfortunately the vibrant nature of school libraries is diminishing as people often view the Internet and electronic resources as a viable alternative to physical and print resources (Wood, 2017; Kachel, 2016). But not all electronic or digital resources are automatically superior to print and physical. Instead physical and electronic texts should be considered equally important within a reading paradigm and a school library context (Mitchell, 2011; Mantei, Lipscombe & Kervin, 2018).

The Library Collection Development and Management Policy or CDMP, requires all resources be assessed and evaluated for function, accuracy and reliability, and this includes both physical and electronic resources. The physical component of a library is fairly straightforward to collect, curate and catalogue, as these resources are owned by the school and can be stored in a specific location for student access. Whereas, most electronic resources have access permitted through leases or subscriptions held by libraries. These subscriptions often describe the licencing for a number of users and terms are often dictated by the publisher. It must be noted that some digital resources can be owned, like purchased electronic books, but leases or subscriptions are more common within libraries.

Electronic resources also vary in their format, require different devices for access, and can suddenly ‘disappear’, which can place additional costs on libraries and users. Some digital resources such as websites and webpages often require close scrutiny to ensure authority. The considerations a teacher librarian has to make to determine suitability for digital and electronic resources are more exacting than for physical and print sources (Johnson, 2018). These considerations, or selection criteria are used to differentiate an electronic source’s credibility, reliability accuracy, authority and importantly, price. It’s the CRAAP test for librarians.

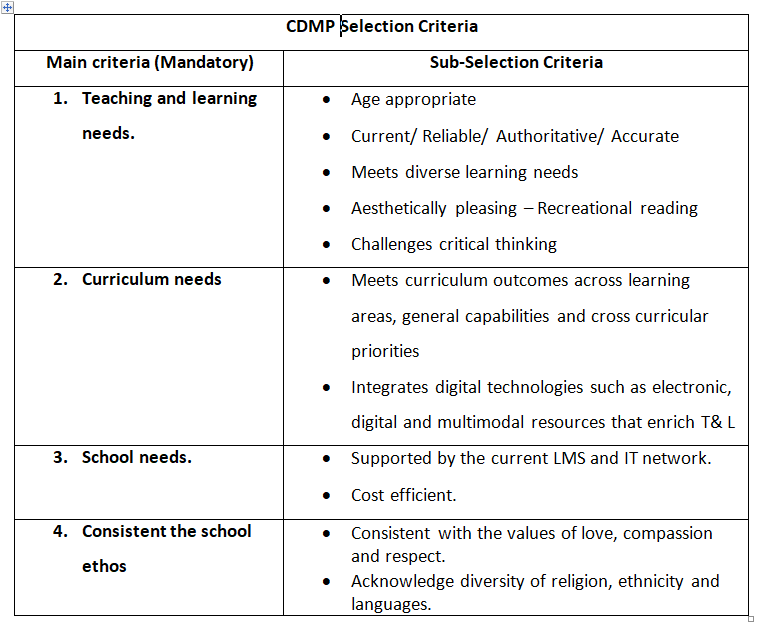

Hughes- Hassell & Mancall (2005) advocates the use of a flow chart to determine suitability, whereas El Mhouti (2013) suggests the use of a tree structure that assesses academic, pedagogical, didactic and technical qualities. Whilst I have considered both these options, I do prefer the main criteria and evaluative process by El Mhouti et al., (2013) as it is methodological, and it seems foolhardy to exclude resources should they not meet each and every requirement. Instead, resources should satisfy all the main criteria and at least one of the subsections.

The following selection criteria was created to assess and evaluate resources for a Catholic high school library. These criteria points, whilst not exhaustive aim to cover the essential aims and priorities (Hughes- Hassell & Mancall, 2005; National Library of NZ, n.d.a; ALA OIC, 2018). I have previously covered some of this information in this blog post!

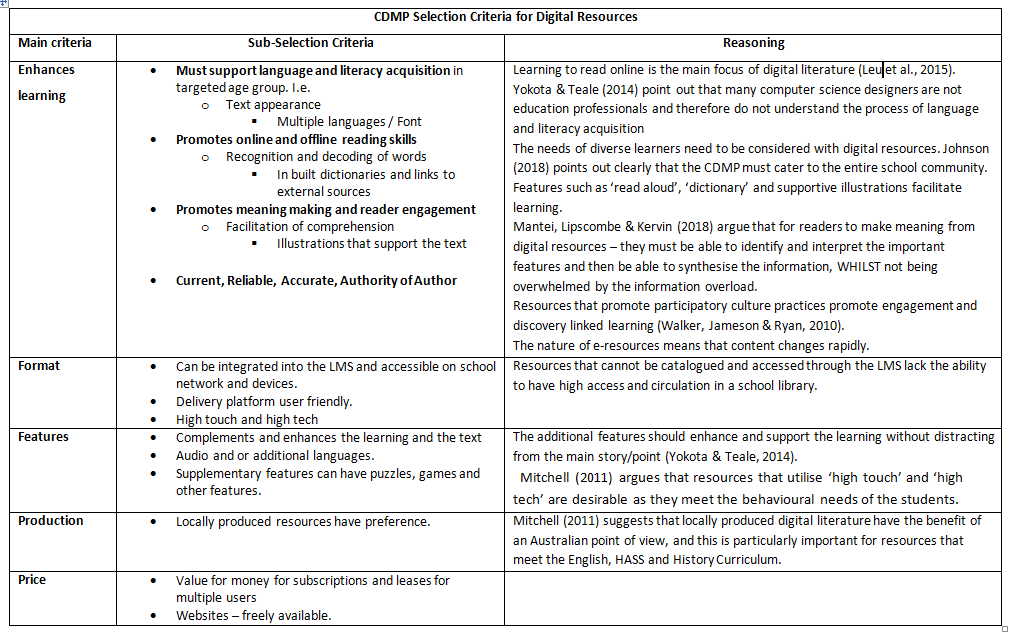

Whilst the above selection criteria are deemed suitable for physical resources, it seems apparent that digital resources require additional considerations (Johnson, 2018, p.128). These considerations will change depending on the school, its digital capability and the needs of its community.

Valid considerations when evaluating digital resources are:

- The essential point of electronic resources and digital literature is to facilitate the learning process. From a literacy perspective, the primary purpose of texts in a digital space is to improve a student’s ability to promote transaction with the text. Engagement, comprehension and evaluation of digital texts require online AND offline reading skills. Offline reading skills such as word recognition, subject specific content vocabulary and meaning making are all essential for online reading (Leu et al., 2015). Whereas online reading requires the reader to locate information, critically evaluate the information present, synthesise multiple sources of information and be able to problem solve (Leu et al., 2015). Resources that DO NOT ENHANCE the learning process, DO NOT BELONG in a school library collection!

- The National Library of New Zealand (n.d.c) points out that libraries are responsible for the curation of digital resources and that they meet the same collection development standards as set in the CDMP. Many teacher librarians use LibGuides as a method to curate digital content, as they are a great way of drawing attention to subject specific resources teaching and learning purposes (German, 2017). Other tools used to curate content include Diigo, Pinterest, PearlTrees, Twitter and Feedly (Nat Lib. of NZ, n.b.c).

- Digital and electronic sources are often used to meet the needs for diverse learners. Students with cognitive, behavioural and developmental learning needs do require resources in different formats and it is the duty of the CDMP to ensure that their policies meet those needs (Johnson 2018). An example is providing access to audiobooks and databases with a “read aloud” function and checking the accessibility of websites to assist with equitable access for students with visual impairments and learning disabilities.

- Leu et al. (2015) argues that instead of teaching students the intricacies of software, it is more important to teach the skills, which can then be transferred across subjects and out of the school environment. This means that online reading and learning needs to be the main focus of digital resources (see above point).

- A concern from many teacher librarians about digital literature is the issue of copyright (Sahoo & Goel, 2018). The internet has made it very easy to infringe these rights. Therefore any resources added to the school library collection need to be sourced ethically and the author clearly sited on the source.

- Digital resources need to be supported by the school’s network and LMS, and if BYOD program exists, licensing that permits multiple users (IFLA 2015). Many online libraries such as BorrowBox and Wheelers only permit one user at a time to access their collection. Whilst this is appropriate and acceptable for public libraries, it does not work for texts used for teaching and learning. In these cases multiple print copies would be more financially sound.

- Emerging technologies such as AR and VR are starting to appear in libraries across the world. Their prevalence is currently limited to academic libraries and public libraries but are starting to emanate in school environments. Mitchell (2011) argues that resources that utilise ‘high touch’ and ‘high tech’ are desirable as they meet the behavioural needs of the students.

(Johnson, 2018; Nat Lib NZ, n.d.c; Hughes-Hassal & Mancall, 2005; El Mhouti, 2014; Yokota & Teale, 2014; Leu et al., 2015; Mantei et al., 2018; Walker et al., 2010; Mitchell, 2011)

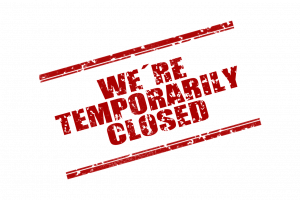

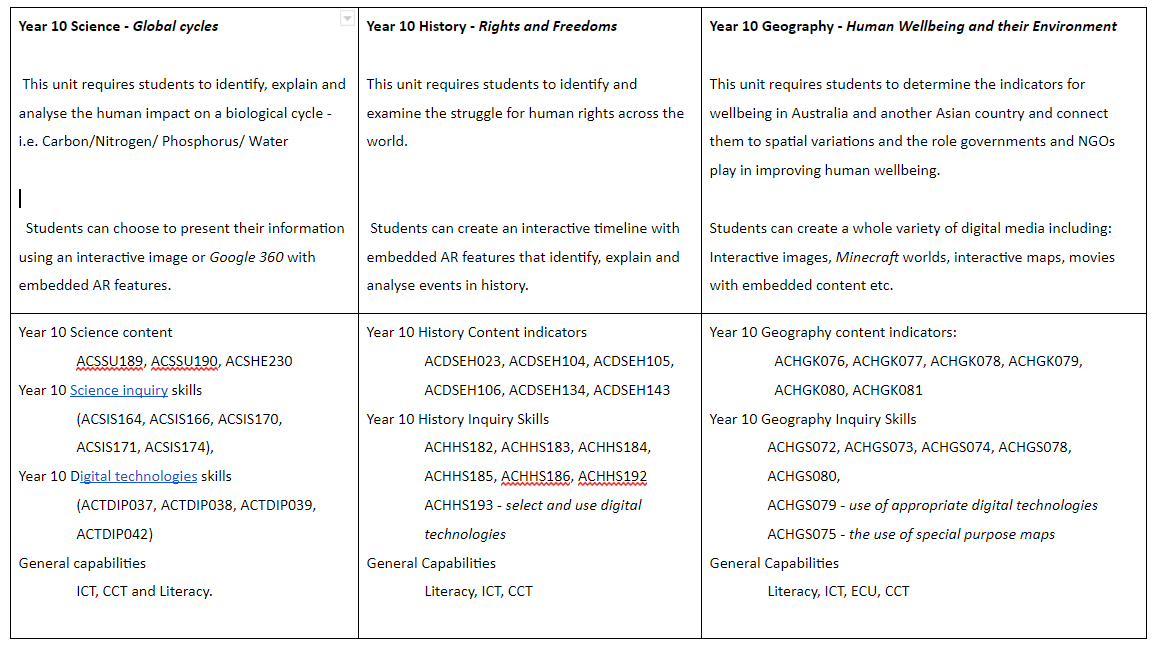

The Australian curriculum requires the inclusion of digital and multimodal texts to support learners in their endeavour to become active citizens in a digital world. The integration of digital resources has a dual purpose in school collections, as it fulfills the learning requirements dictated by ACARA, as well as the contemporary skills the modern student needs (MCEETYA, 2008). Since the focus of a school library is to support and address the curriculum, the CDMP needs to ensure that its selection criteria promotes the curation of reputable and reliable resources in both print and electronic forms. The truth of the matter is that technology is constantly transforming, and with this constant change, the nature of digital and electronic resources available for teaching and learning is adapting at the same pace. This rapid change means CDMP policies are often unable to keep up with technology advances, which means it’s up to the TL to use their discretion when considering the inclusion of digital resources into the school library collection.

REFERENCES:

ALA Office for Intellectual Freedom (2018) Selection & Reconsideration Policy Toolkit for Public, School, & Academic Libraries. American Library Association. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/tools/challengesupport/selectionpolicytoolkit/criteria

El Mhouti, A., Nasseh, A., & Erradi, M. (2013). How to evaluate the quality of digital learning resources? International Journal of Computer Science Research and Application. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260392089_How_to_evaluate_the_quality_of_digital_learning_resources

German, E. (2017). LibGuides for instruction – A service design point of view from an academic library. Reference and User Services Quarterly 56(3). Retrieved from https://www.journals.ala.org/index.php/rusq/article/download/6257/8146

Hughes-Hassell, S., & Mancall, J. C. (2005). Collection management for youth : Responding to the needs of learners. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com

IFLA (2015 ) IFLA School library guidelines. 2nd Edition. International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions. Retrieved from

Kachel, D. (2015). The calamity of the disappearing school libraries. The Conversation. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/the-calamity-of-the-disappearing-school-libraries-44498

Jong, M. (2019). Sustaining the adoption of gamified outdoor social enquiry learning in high schools through addressing teachers’ emerging concerns: A 3-year study. British Journal of Educational Technology 50(3). Pp1275-1293. DOI: 10.1111/bjet.12767

Learning for the future: developing information services in Australian schools 2nd edition (2001). Curriculum Corporation, Carlton South. Retrieved from http:// www.curriculumpress.edu.au/main/goproduct/12405.

Leu, D.J, Forzani, E.,Timbrell, N., & Maykel., C. (2015) . Seeing the forest, not the trees: Essential technologies for literacy in primary grade and upper elementarty grade classroom. Reading Teacher 69: (2), p.139-145. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1073399.

Mantei, J., Kipscombe, K., & Kervin, L. (2018). Literature in a digital environment (Ch. 13). In L. McDonald (Ed.), A literature companion for teachers. Marrickville, NSW: Primary English Teaching Association Australia (PETAA).

MCEETYA (2008) Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians. Curriculum Corporation. Australia. Retrieved from http://www.curriculum.edu.au/verve/_resources/national_declaration_on_the_educational_goals_for_young_australians.pdf

National Library of New Zealand. (n.d.a). Selecting and purchasing resources. Service to Schools. Retrieved from https://natlib.govt.nz/schools/school-libraries/collections-and-resources/selecting-resources-for-your-collection/selecting-and-purchasing-resources

National Library of New Zealand (n.d.b) Working out your library’s collection requirements. Service to Schools. Retrieved from https://natlib.govt.nz/schools/school-libraries/collections-and-resources/your-collection-management-plan/working-out-your-librarys-collection-requirements

National Library of New Zealand, (n.d.c). Your library’s digital collection. Service to Schools. Retrieved from https://natlib.govt.nz/schools/digital-literacy/your-librarys-role-in-supporting-digital-literacy/your-librarys-digital-collection

Sahoo, B., Kumar, A. & Goel, S. (2018). Digital resources management: The role of the National Digital Library. International Journal of Information Dissemination and Technology, 8(3), 143-146.

Walker, S., Jameson, J., & Ryan, M. (2010). Chapter 15 – Skills and strategies for e-Learning in a participatory culture. In Sharpe, R., Beetham, H., & de Freitas, S. (2010). Rethinking Learning for a Digital Age. Retrieved from CSU library.

Wood, P. (2017). School libraries disappearing as the digital age takes over. ABC News Breakfast. Retrieved from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-09-25/school-libraries-disappearing-as-the-digital-age-takes-over/8980464

Yokota, J., & Teale, W. (2014). Picture books and the digital world. The Reading Teacher 67(8), pp.577-585. DOI: 10.1002/trtr.1262