PART C – THE REFLECTING

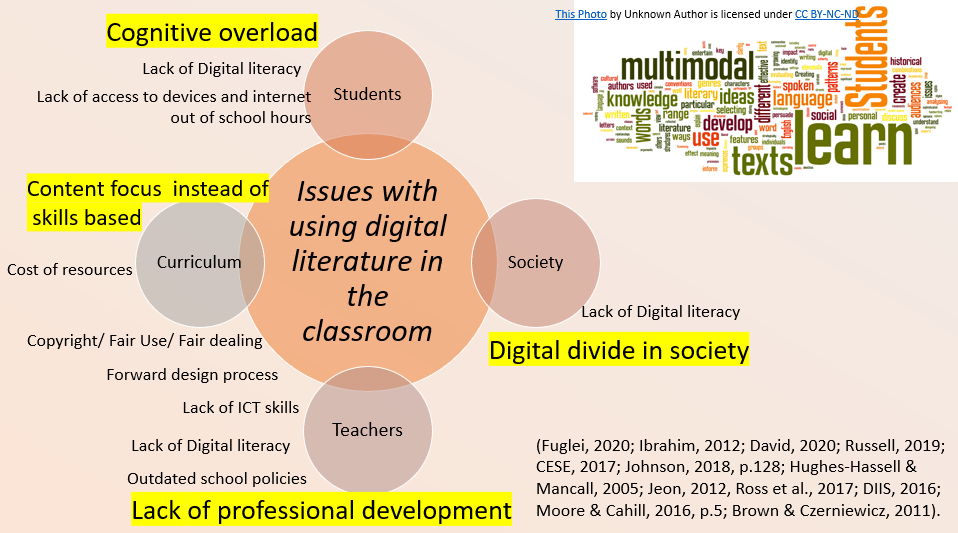

The shift in the reading paradigm has impacted the definition of reading and the parameters of a text (ACARA, 2018; Lamb, 2011). Literacy is now defined as the ability to effectively engage with and communicate with a range of modalities (ACARA, 2018). Even though ACARA (2018) has mandated the incorporation of print, digital and hybrid literature, the inclusion of hybrid and digital literature in educational practice does have an impact on student learning, teacher confidence, and the nature of copyright when sharing digital works.

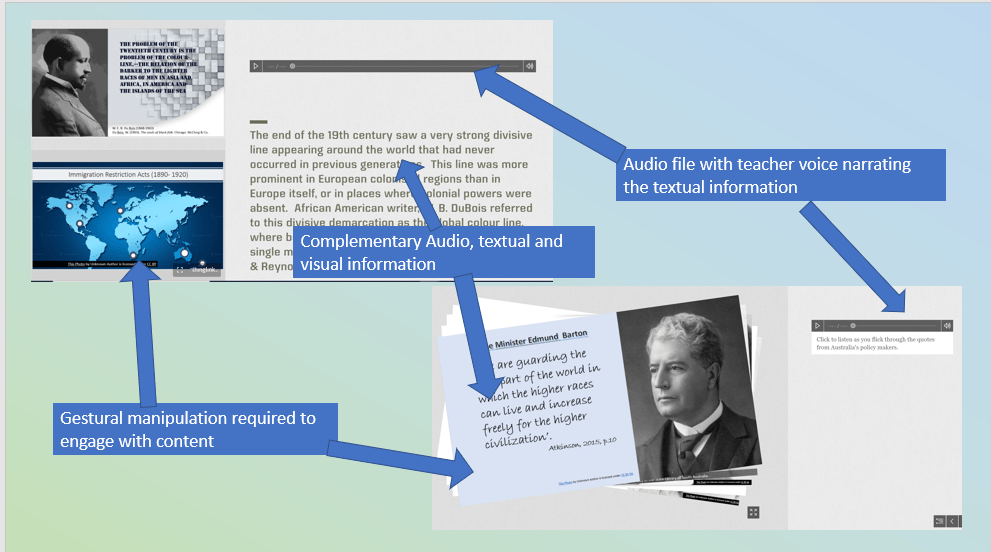

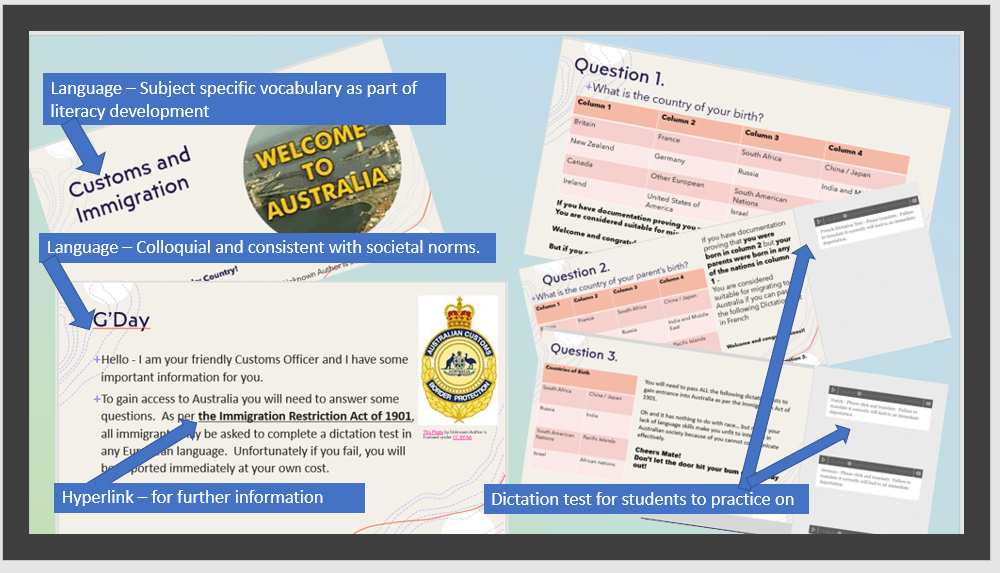

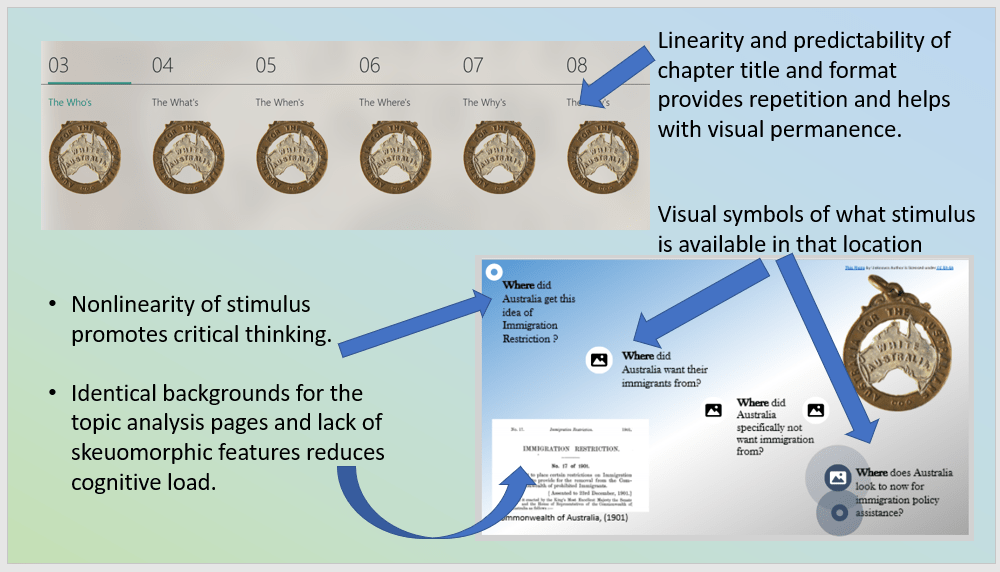

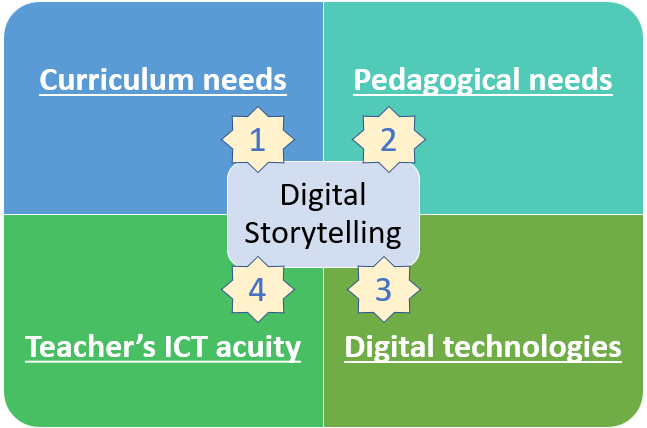

Digital storytelling (DST) is the modern adaptation of the ancient art of storytelling, in which visual, audio and textual elements are interwoven together to convey information and develop critical thinking (Ciccorico, 2012; Ohler, 2013, p.94; Maneti, Lipscombe & Kervin, 2018). DST is also an effective conduit of knowledge, and traditions but its primary purpose is to develop language, literacy, and learning (Moran et al., 2020; Ross Johnston, 2014). From an education perspective, DST can improve multimodal literacies, digital competencies and critical thinking, as it requires the reader to interact with the content rather than just passively view it (Hashim & Vongkulluksn, 2018). The issue with utilising DST is that not all DL is transformative, and not all recipients possess the necessary skills to access and engage with the medium (Ross et al., 2017; Jeon, 2012). DST that have minimal gestural manipulation, contradictory modalities, poor layout, and a lack of visual permanence have lower comprehension compared to print texts (Lamb, 2011; Hashim & Vongkulluksn, 2018).

The issues with students:

The ability to process information is known as cognitive load. Mayer and Moreno (2005) point out that cognitive overload occurs the amount of information received supersedes the brain’s processing capacity and any excess of stimuli can lead to diminished transfer of knowledge and reduced learning outcomes (CESE, 2017, p.3). Cognitive load is minimised when skeuomorphic features are curtailed, modalities are complementary and when students have appropriate digital literacy skills (Ibrahim, 2012; Mangen et al., 2013). Other factors that increase cognitive load are visual permanence, layout, colour scheme, length of digital text and an appropriate level of content (Mayer & Moreno, 2005; Mangen et al., 2013). The review of my own DST shows how I attempted to meet the needs of my students.

The issues with practitioners:

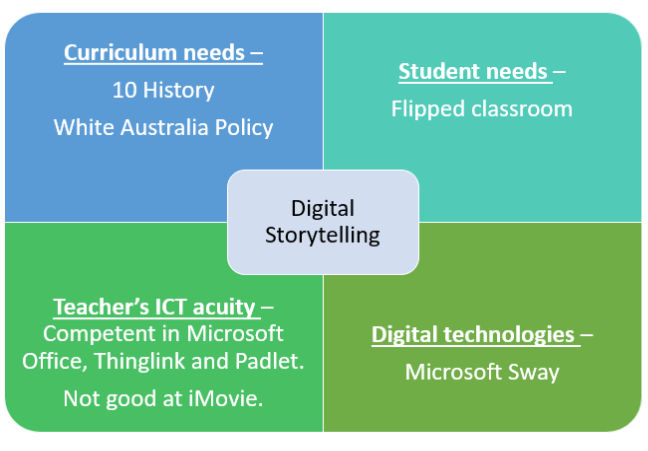

ACARA (2018) and ATSIL (2017) both require the inclusion of digital literature into classroom practice, but this mandate can cause feelings of inadequacy and can be exacerbated by the volume and variety of technology available (Hyndman, 2018). However, Watson (2019) points out that teachers do not have to become experts in all forms of technology, just the platform they are choosing to use. This resonates as in the first assessment task for INF533, I pointed out that teachers were unlikely to include creation of DST in their practice due to concerns of their own digital competencies (Templeton, 2020). McGarr & McDonagh (2019) suggest that teacher competence should be framed around technology, cognition and ethics, so that professional development can have a focus. Read about my DST journey here.

The issue with copyright:

The integration and implementation of DL has legal ramifications, and whilst educators are familiar with the “10% or one chapter rule”, there is a significant proportion who are unsure of the legalities when it comes to digital resources, Creative Commons and copyright law (Suzor, 2017). Literacy Toolkit (2019) points out that modelling correct academic writing for students with appropriate citations, is an effective way of explicitly teaching academic honesty. An added benefit of using the Office suite is that Creative Commons images can be utilised with ease. It was also fascinating to learn that images from historical and current events do not require permission for reporting purposes, and that transformed resources do not breach copyright law as it is unlikely to affect the creator or harm the market (ALRC report, 2013, p.319; Suzor, 2017). Therefore teachers that create and or transform media to suit the needs of their students, are less likely to breach copyright than educators that just copy resources. I certainly wish I had known this prior to starting and finishing my digital narrative, but that is for another blog on another day.

This semester expanded my knowledge of digital literature as indicated by my EVIDENCE of LEARNING hierarchal chart.

In creating this Sway narrative, I was able to build upon understanding gained from previous subjects and solidify new knowledge upon it. I learned about :

- Debunking the digital native myth.

- Understanding the relationship between teens, trends and technology

- Understanding the classroom divide, the evolving nature of literature and how digital literature increases motivation.

- Determining collection parameters for digital literature

- Creating a rubric for evaluating digital resources

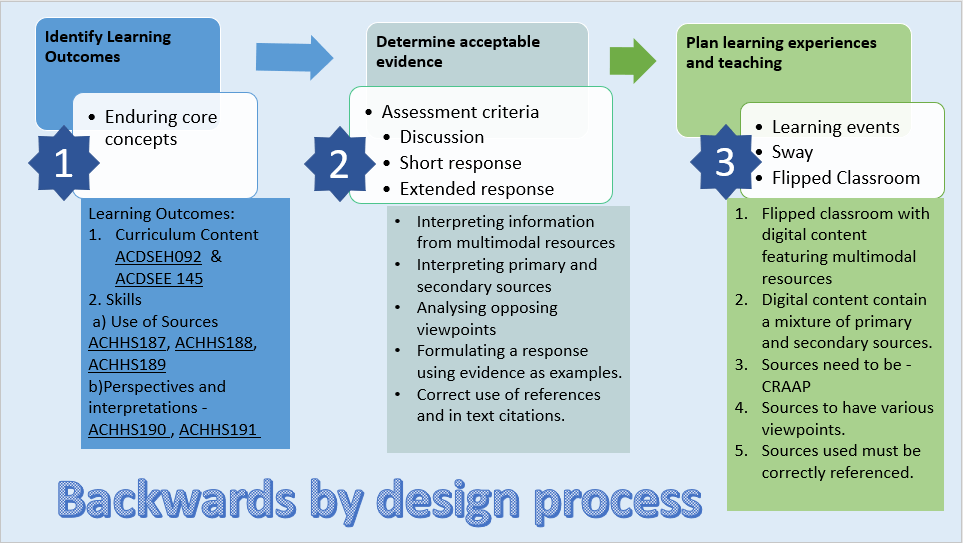

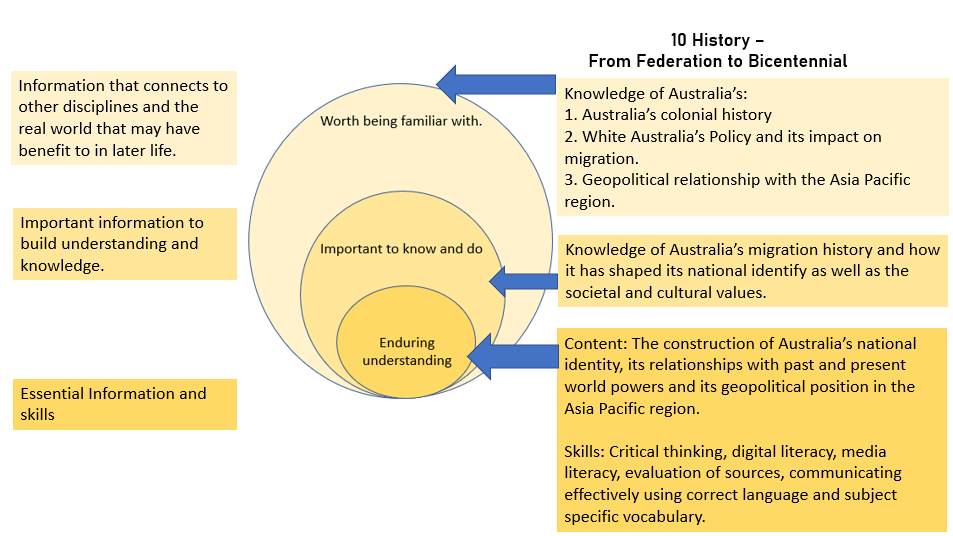

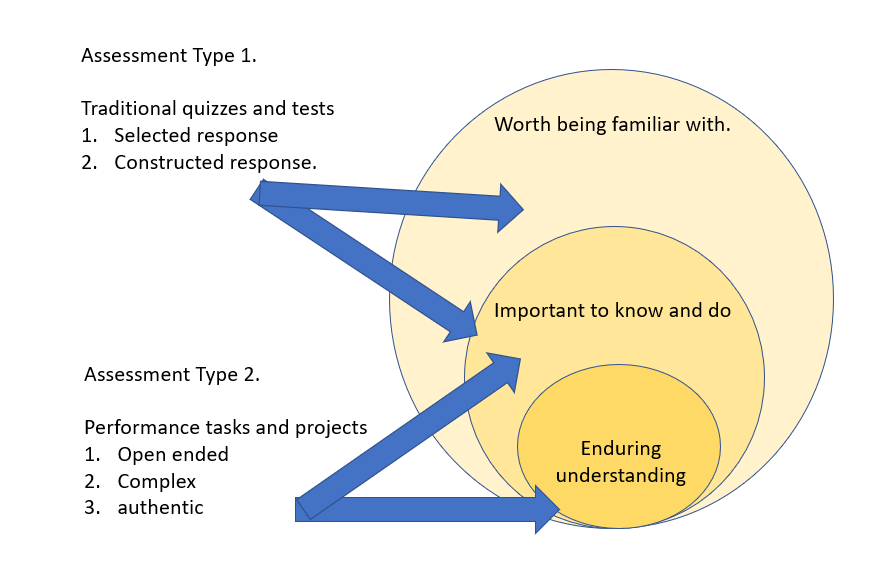

- Determining the curriculum outcomes using the Backwards by design process.

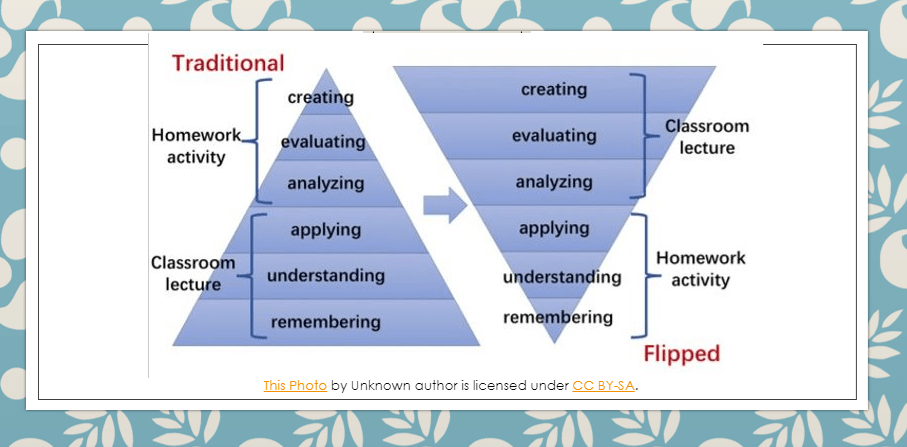

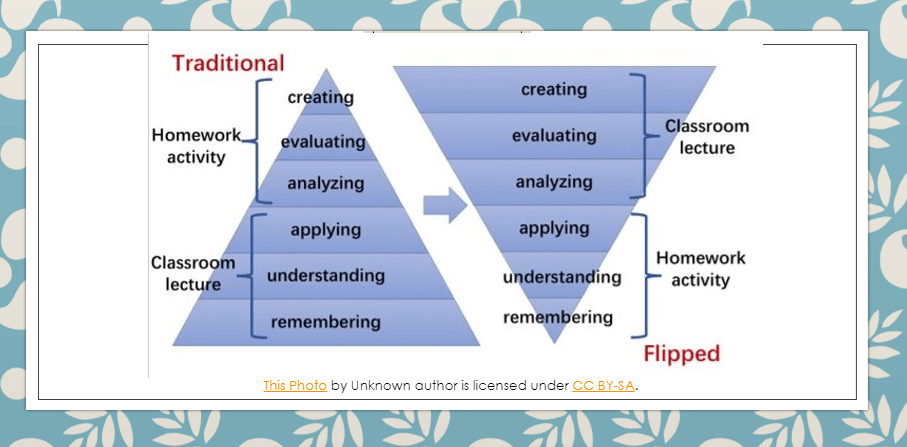

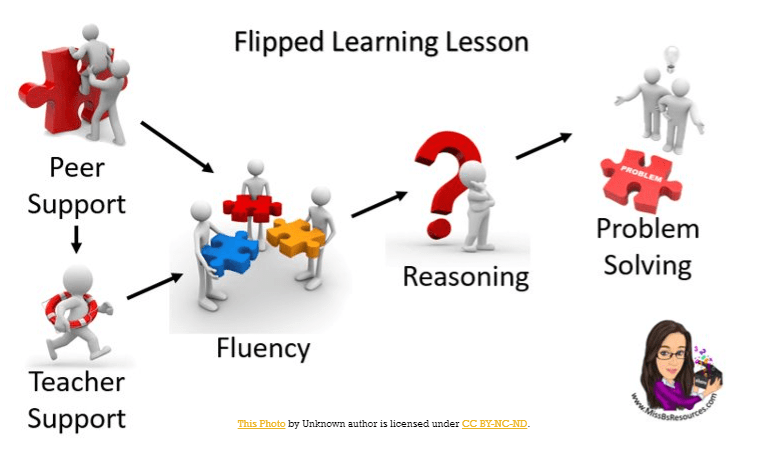

- Understanding the dynamics of a flipped classroom

- Understanding the relationship between multimedia and cognitive load.

- Exploring the legalities of copyright law in the classroom (Blog yet to be written) and the need to explicitly teach copyright ethics.

- Evaluating the process of creating a DST.

- Lastly, evaluating my own DST using the same parameters I designed for Assessment task 2.

This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-SA-NC

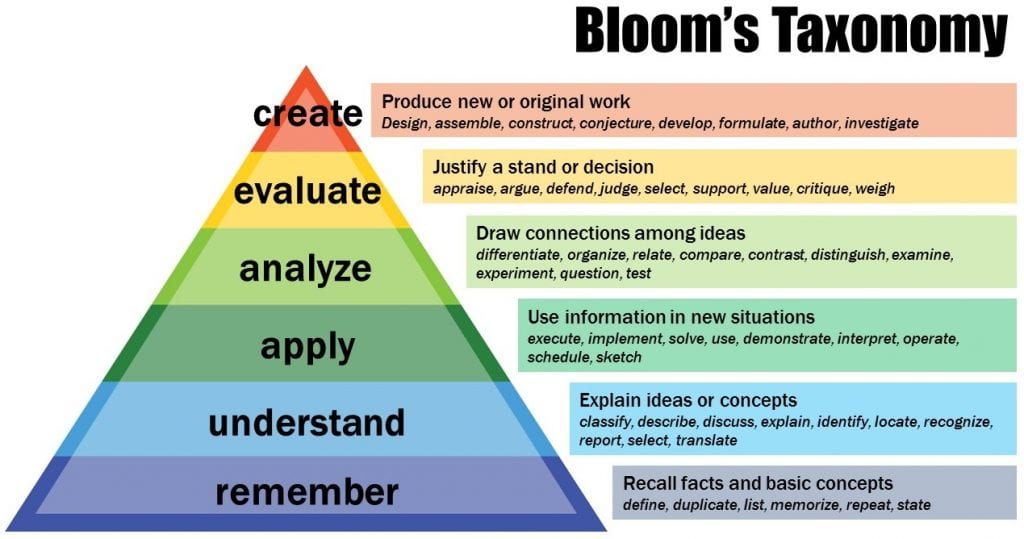

Remember Bloom? That’s why.

REFERENCES

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. (2018). Literacy. In Australian Curriculum – General Capabilities. Retrieved from https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/general-capabilities/literacy/

Australian Government. (2013). Copyright and the digital economy (ALRC Report 122). Australhttps://www.alrc.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/final_report_alrc_122_2nd_december_2013_.pdfian Law Reform Commission.

AITSL. (2017). Standards for Teachers. Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership. Retrieved from https://www.aitsl.edu.au/teach/standards

Brown, C., & Czerniewicz, L. (2010). Debunking the ‘digital native’: beyond digital apartheid, towards digital democracy. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 26(5). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2010.00369.x

Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation. (2017). Cognitive load theory: Research that teachers really need to understand. NSW Department of Education. Retrieved from https://www.cese.nsw.gov.au//images/stories/PDF/cognitive-load-theory-VR_AA3.pdf

Ciccoricco, D. (2012). Chapter 34 – Digital fiction – networked narratives. In Bray, J., Gibbons, A., & McHale, B. (2012). The Routledge Companion to Experimental Literature. Taylor & Francis eBooks. Retrieved from CSU Library.

David, L. (2020). Cognitive theory of multimedia learning (Mayer). Learning Theories. Retrieved from https://www.learning-theories.com/cognitive-theory-of-multimedia-learning-mayer.html

Department of Industry, Innovation and Science. (2016). Australia’s digital economy update. Retrieved from https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2016/05/apo-nid66202-1210631.pdf

Fuglei M. (2020). Begin at the end: How backwards design enriches lesson planning. The Resilient Educator. Retrieved from https://resilienteducator.com/classroom-resources/backwards-design-lesson-planning

Hashim, A & VongKulluskn, V. (2018). E reader apps and reading engagement: A descriptive case study. Computers and Education, 125, pp.358-375. Retrieved from https://www.journals.elsevier.com/computers-and-education/

Hughes-Hassell, S., & Mancall, J. C. (2005). Collection management for youth : Responding to the needs of learners. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com

Hyndman, B. (2018). Ten reasons teachers can struggle to use technology in the classroom. The Conversation [Blog]. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/ten-reasons-teachers-can-struggle-to-use-technology-in-the-classroom-101114

Ibrahim, M. (2012). Implications of designing instructional video using cognitive theory of multimedia learning. Critical Questions in Education 3(2), p.83-104. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1047003

Jeon, H. (2012). A comparison of the influence of electronic books and paper books on reading comprehension, eye fatigue, and perception. The Electronic Library, 30(3), 390-408. doi: 10.1108/02640471211241663

Johnson, P. (2018). Chapter 4 – Developing Collections. Fundamentals of Collection Development 4th Edition. ALA Editions. Chicago. Retrieved from EBSCOhost Books.

Korthagen, F. (2017). Inconvenient truths about teacher learning: towards professional development 3.0. Teachers and Teaching, 23(4), p.387-405. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/13540602.2016.1211523?needAccess=true

Kurt, S. (2018). What is backward design. Educational Technology. Teaching and Learning Resources. Retrieved from https://educationaltechnology.net/backward-design-understanding-by-design/

Lamb, A. (2011). Reading redefined for a transmedia universe. Learning and leading with technology, 39(3), 12-17. Retrieved from CSU Library

Mangen, A., Walgermo, B. R. & Bronnick, K.A. (2013). Reading linear texts on paper versus computer screen: Effects on reading comprehension. International Journal of Educational Research, 58, 61-68.doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2012.12.002

Mantei, J., Kipscombe, K., & Kervin, L. (2018). Literature in a digital environment (Ch. 13). In L. McDonald (Ed.), A literature companion for teachers. Marrickville, NSW: Primary English Teaching Association Australia (PETAA).

McGarr, O., & McDonagh, A. (2019). Digital competence in teacher education. Output 1 of the Erasmus+ funded Developing Student Teachers’ Digital Competence (DICTE) project. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331487411_Digital_Competence_in_Teacher_Education

Moore, J., & Cahill, M. (2016). Audiobooks; Legitimate ‘reading’ material for adolescents? Research Journal of the American Association of School Librarians. Retrieved from www.ala.org/aasl/slr/volume19/moore-cah

Moran, R., Lamie, C., Robertson, L., & Tai, C. (2020). Narrative writing, digital storytelling, and coding: Increasing motivation with young readers and writers. Australian Literacy Educators Association, 25 (2), p.6-10. Retrieved from https://primo.csu.edu.au/permalink/61CSU_INST/15aovd3/cdi_gale_infotracacademiconefile_A627277934

Ohler, J.B. (2013). Digital storytelling in the classroom: New media pathways to literacy, learning, and creativity (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin. Retrieved from https://primo.csu.edu.au/permalink/61CSU_INST/1hkg98a/alma991012780180302357

Ross, B., Pechenkina, E., Aeschliman, C., & Chase, AM. (2017). Print versus digital texts: understanding the experimental research and challenging the dichotomies. Research in Learning Technology 25. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1163201.pdf

Ross Johnston, R. (2014a). Chapter 23 – Literature, the curriculum and 21st-century literacy. In G. Winch, R. Ross Johnston, P. March, L. Ljungdahl & M. Holliday (Eds.), Literacy: Reading, writing and children’s literature (5th ed., pp. 472-489). Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Russell, D. (2019). An introduction to cognitive load theory [Features]. Teacher Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.teachermagazine.com.au/articles/an-introduction-to-cognitive-load-theory

Suzor, N. (2017). Explainer: what is ‘fair dealing’ and when can you copy without permission? [Blog]. The Conversation. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/explainer-what-is-fair-dealing-and-when-can-you-copy-without-permission-80745

Templeton, T. (2020). Task 1 – INF533 – Reading, literacy and digital literature in the classroom [Blog]. Trish’s Trek into BookSpace. Retrieved from https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/trish/2020/07/26/task-1-inf533-reading-literacy-and-digital-literature-in-the-classroom/

Victorian Department of Education. (2020). Intellectual Property and Copyright. Retrieved from https://www2.education.vic.gov.au/pal/intellectual-property-and-copyright/policy

Victorian Government. (2020). Using third party copyright material – Fact sheet for agencies. Department of Treasury and Finance. Retrieved from https://www.dtf.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/document/Fact%20Sheet%20-%20using%20third%20party%20copyright%20material.pdf

Vidales-Bolanos, M., & Sadaba-Chalezquer, C. (2017). Connected Teens: Measuring the Impact of Mobile Phones on Social Relationships through Social Capital. Media Education Research Journal 53(25). Retrieved by https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1171085.pdf

Walsh, M. (2013). Literature in a digital environment (Ch. 13). In L. McDonald (Ed.), A literature companion for teachers. Marrickville, NSW: Primary English Teaching Association Australia (PETAA).

Watson, A. (2019). 10 tips to avoiding technology overwhelm. The Cornerstone for Teachers [podcast]. Retrieved from https://thecornerstoneforteachers.com/truth-for-teachers-podcast/10-tips-avoiding-technology-overwhelm/