Once upon a time, when the air was clear, there lived a family of moths with pretty white

wings speckled with black spots. This moth thrived in the woodland, blending in nicely with the fungus covered trees, living merrily among the birds, bees and butterflies of 18th century England. Their cousins, the melanic moths, with their black wings were the poor cousins that hid in the shadows, hiding from the daylight hours that would highlight them against the drab grey green tree trunks.

Courtesy of Flickr

But then, darkness descended upon them. The Industrial age had arrived and with it, smog and soot filled the air and covered the trees. The poor little speckled moths stood out with their white wings and soon became prey to all the predators around them. They were dismayed and cried for help to their unfortunate cousins. Instead, the tides had turned. It was the time for the melanic moth to fly. Their black wings blended in with the soot and coal dust covered trees and buildings. It was their time!! It was their day!! But, being the kind and caring moths, they shared their genetic material with their erstwhile peppery cousins and soon their little speckled moth cousins became black too and life was merry.

Courtesy of Flickr

Adaptation. The ability to adjust or change your behaviour, physiology or structure to become more suited to the environment (NAS 2019). Those peppered moths defied extinction by adapting to the world around them.

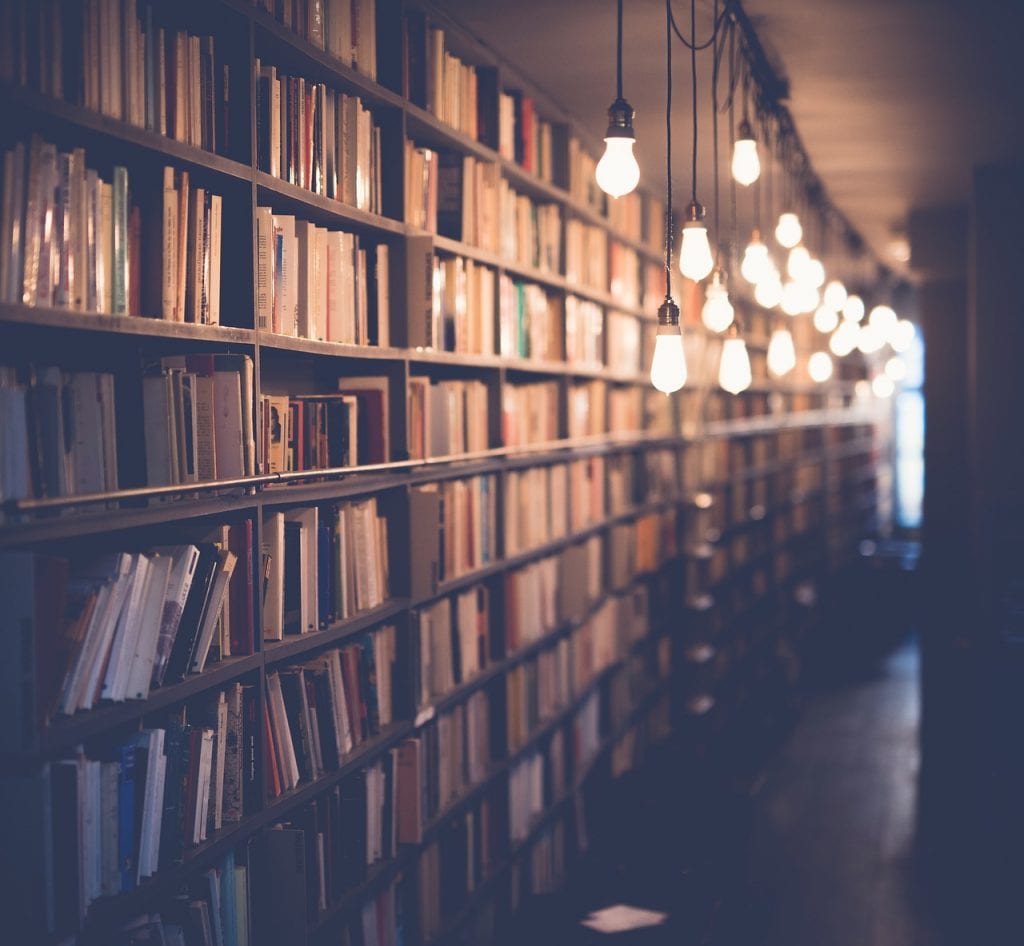

This is exactly what libraries have done. They have evolved from hallowed grounds, sanctified and silenced by volumes of knowledge,held in trust for the future generations; to hubs of energy and have completely embraced this fourth age, known as the digital age. This digital age, Rouse (2005) elaborates is one in which information, its control, creation and conferment are the basis of the economy. Individuals who are not actively involved cannot call themselves digital citizens and the ramifications of this are immense. But thats a whole other post – Read it now.

Back to libraries and teacher librarians. Have they become an endangered species?

Arguably, everything in the modern world is at risk from extinction with the advent of automation and technology. An article from the Guardian (2017) finds that in about 60% of occupations would face partial employment reduction due to aspects being phased out by technology. Combined with BBC News (2016) doomsday report about the slow extinction of libraries, one could extrapolate that teacher librarian role would soon become a figment of the past and unable to exist with the digital age.

BUT THEY ARE WRONG!

Teacher librarians are another of these defiant species. Like our moth mates, rather than lay stagnant and shrink away, teacher librarians, consummate professionals as always, have embraced the digital age and evolved with it. Libraries are now filled with computers and other technology. Wifi is synonymous with public libraries and Burton (2017) found that almost a third of patrons visit a library just to access the internet. For many, libraries are the bridge between them and rest of the world. Burton (2017) points out that libraries are becoming the information hubs of society by providing this crucial access to information

Courtesy of Flickr

The question though lies, whilst libraries have evolved into knowledge hubs, has society as a whole, sufficiently evolved to engage with this new age of information. Is the world equipped to work with Google?

Besides providing access to technology, librarians more importantly provide programs that teach digital literacy. Todd (2012) found that whilst there is an obvious trend in the proliferation of personal digital devices, and that this technology is the dominant platform for information access and use, he did query the ability of students to actually engage with the content and its medium.

The question must be asked… are young people, who have used an ipad before a crayon actual able to navigate the digital world successfully? Are they able to use this technology for more than just games and social media? If not, then how are they going to become citizens of this digital world. Herring (2007) theorized that students needed to be taught how to use search engines based upon the evaluation and understanding of the content rather than the simple act of seeking an answer. As you can plainly see, the demand is for digital citizenship education.

Digital education most commonly happens in schools and and theoretically are programmed into the curriculum by a qualified teacher librarian. But these days of tightening budgets, schools are often forgoing the need for a qualified teacher librarian and replacing them by either a classroom teacher or an administrator, often under the false assumption that Google can solve everything.

The problem with this is according to Bonnano (2015) is that the specialist skills that a TL brings is missing, such as understanding learner needs, comprehensive knowledge of the curriculum INCLUDING the general capabilities. Todd (2012) goes on further to say that teacher librarians have “recognised multimodal nature of literacies that emerged from digital environments and its importance of addressing these literacies”. It is information expert component of a teacher librarian role that can ensure these literacies are addressed properly (ALIA & ASLA 2016a).

Teacher librarians are tasked by ALIA/ASLA (2016b) to implement programs that embed information literacy within the curriculum so that students become adept at seeking and using relevant and authoritative information. It is our profession duty, that we teach students to be able to analyse, create and disseminate information ethically in multiple formats. Teacher librarians are tasked with ensuring that students become active and informed digital citizens.

The absence of a school library and or the absence of a qualified teacher librarian will only be detrimental to the educational outcomes of the learning community. It is clear to me that the presence of a teacher librarian is essential for the educational outcomes of the students. Teacher librarians are certainly not endangered, rather I think the profession will soon become a necessity if society is to survive.

References

ALIA and ASLA (2016a) Statement on teacher librarians in Australia. Retrieved from

https://asla.org.au/resources/Documents/Website%20Documents/Policies/policy_tls_in_australia.pdf

ALIA and ASLA (2016b) Statement on information literacy. Retrieved from https://asla.org.au/resources/Documents/Website%20Documents/Policies/policy_Information_Literacy.pdf

BBC News (2016) Libraries: The Decline of a profession? England. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-35724957

Bonanno, K,. (2015) A profession at the tipping point (revisited). Access. Retrieved from http://kb.com.au/content/uploads/2015/03/profession-at-tipping-point2.pdf

Burton, S., (2017) Does the digital world need libraries. [BLog] Internet Citizen. Retrieved from https://blog.mozilla.org/internetcitizen/2017/09/04/libraries/

The Guardian (2017) What jobs will still be around in 20 years? Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/jun/26/jobs-future-automation-robots-skills-creative-health

Herring, J., (2007) Libraries in the 21st Century. Chapter 2. Retrieved from https://www-sciencedirect-com.ezproxy.csu.edu.au/science/article/pii/B9781876938437500028

National Academy of Science (2019) Definitions of Evolutionary terms. National academies of Sciences, Engineering Medicine. Retrieved from http://www.nas.edu/evolution/Definitions.html

(Purcell, M. (2010). All librarians do is check out books right? A look at the roles of the school library media specialist. Library Media Connection 29(3), 30-33

Todd, Ross J. School libraries as pedagogical centres [online]. Scan: The Journal for Educators, Vol. 31, No. 3, Aug 2012: 27-36. Availability: <https://search-informit-com-au.ezproxy.csu.edu.au/documentSummary;dn=585228491693277;res=IELHSS> ISSN: 2202-4557.