Introduction:

Leaders and leadership traits are found all throughout a learning organisaiton’s stratums. However, the difference between the hierarchies is how leadership is exhibited. The principal and their executive team are the traditional leaders in schools as they are the ones that hold formal roles and any decision they make has the weight of that authority behind them. These upper leadership styles are often directive and or distributive in nature to ensure a learning organisation is effective at improving student outcomes (Supovitz, D’Auria & Spillane, 2019, p.8). However, leadership activity regularly occurs outside the executive team as there are many instances of classroom teachers exhibiting leadership traits within their spheres of influence (De Nobile, 2018). They are known as teacher leaders, and they have a great capacity to influence a school system and improve learning outcomes because they base their leadership upon the relationships they have with their colleagues, and their communities (Uribe-Florez, Al-Rawashdeh & Morales, 2014, p.1). Their efficacy is framed upon the simple fact that these teacher leaders are primarily situated in the classroom, have a thorough understanding of student learning and thus have a greater impact on student success (Consenza, 2015, p.80).

Defining teacher leaders:

Teacher leaders are predominantly classroom teachers who use their social influence and leadership capacity to effect educational change in their school (Uribe-Florez, Al-Rawashdeh & Morales, 2014, p2). They often hold a variety of roles and their influence can stem from two main sources, a desire to seek career advancement through investigating appropriate professional challenges, or by building relationships and trust with their peers to create a professional network (Fairman & Mackenzie, 2015; Cosenza, 2015, p.79; Riveros, Newton & da Costa, 2012, p.2). Either way, teacher leaders do not hold any formal positions within the school, but instead use their expertise, professional knowledge and practice to inspire and motivate their peers.

Historically teacher leaders were perceived as more of a managerial position. But it soon became evident that their expertise was more suited to improving pedagogy, and thus the second wave of leadership saw teacher leadership focused upon instruction and curriculum development before finally evolving into leaders of modern pedagogical practice (Fairman & Mackenzie, 2015, p61). Riveros, Newton & da Costa, (2013) suggest that teacher leader efficacy is based upon the fact they are process orientated and have significant knowledge and understanding of the curriculum and classroom teaching strategies (p.2-3). Interestingly, both Fairman & Mackenzie (2015), and Riveros, Newton & da Costa (2013) theories that the efficacy of teacher leaders is due to informal leadership positions having a far greater potential to impact pedagogical practices and change management because influence is gained through relationships rather than stemming from a power base.

Teacher leaders and their role in teaching and learning:

There are several advantages to developing teacher leaders in schools but the predominant benefit is the indirect improvement of student learning outcomes through the direct impact of improving pedagogical practice (Riveros, Newton & da Costa, 2013, p.2). These pedagogical improvements can be implemented by the teacher leader using servant leadership, such as modelling best practice, mentoring emerging teachers, sharing new ideas, as well as taking action and collaborating on school wide initiatives (Riveros, Newton & da Costa, 2013, p.2; Cosenza, 2015). Whilst some teacher leaders have specific roles such as teacher librarian, ICT leader, digital coach, literacy leader or even just be known as the ‘math guru’, they are predominantly classroom teachers who are seeking to improve their own professional practice (Riveros, Newton & da Costa, 2013, p.2). The commonality between the various roles and practices is that these teacher leaders have the ability to effectively collaborate with their colleagues for the benefit of all the school’s stakeholders (Cosenza, 2015, p.93).

Teacher leaders and change management:

The efficacy of a teacher leaders’ ability to be a change agent and implement school wide improvements is framed upon their leadership abilities, and their capacity to collaborate effectively with their peers horizontally across the learning organisation. Leadership traits such as having a strong sense of purpose, developing robust relationships, and advocating collaboration to improve teaching and learning beyond the walls of their classroom are essential to improve school wide practice (Riveros, Newton & da Costa, 2013, p.2). It is through these behaviours and attributes that teacher leaders are able to directly influence change by initiating professional conversations, promoting collegial discussions, mentoring emerging teachers, sharing innovative ideas as well as by collaborating with their colleagues on curriculum, assessment and reporting (Fairman & Mackenzie, 2015, p72). They can also indirectly influence how change is implemented by promoting a positive learning environment and by developing teams to facilitate the change management process (Fairman & Mackenzie, 2015, p. 73).

As teacher leaders are defined by their skills and actions rather than a formal role or position, they can arise from any faculty across a school (Consenza, 2015, p.80). This means that they are able to have an immediate impact on their sphere of influence, and when they collaborate with their colleagues, their spheres of guidance expands and as such, their activity becomes a collaborative exercise (Fairman & Mackenzie, 2015, p 63). These spheres of activity and corresponding impact allows teacher leaders to become innovators of pedagogy because they are able to use their positive relationships with their peers to influence teaching practices in their schools, and build collegial environments in their professional communities (Fairman & Mackenzie, 2015, p.68).

Teacher librarian as a teacher leader:

Teacher librarians can be considered as teacher leaders because their professional practice requires them to have a comprehensive understanding of curriculum, use evidence to support pedagogy, advocate lifelong learning, demonstrate leadership, promote collaborative practices and create an environment that promotes participation and learning (Johnston, 2015, p. 40; ALIA & ASLA, 2004). In fact these requirements correlate closely to the qualities described in AITSL (2019) Highly Accomplished and Lead Teacher domains, therefore confirming teacher librarians as teacher leaders. In fact, many teacher librarians are distributed the role of leadership of information literacy, innovative pedagogies and emerging technologies as part of shared leadership because they are best suited to that role (Johnston, 2015, p.40).

Through their capacity as teacher leaders, teacher librarians are able to develop positive relationships with their peers, and are able to effectively implement innovative pedagogies as well as embed emerging technologies into teaching and learning (Lipscombe et al., 2020, p.412). These behaviours are made possible because the relationships are based upon a shared professional identity, and a reciprocal of trust which creates the library as a safe place for teachers to experiment without fear of any reprisals (Riveros, Newton & da Costa, 2013, p.10).

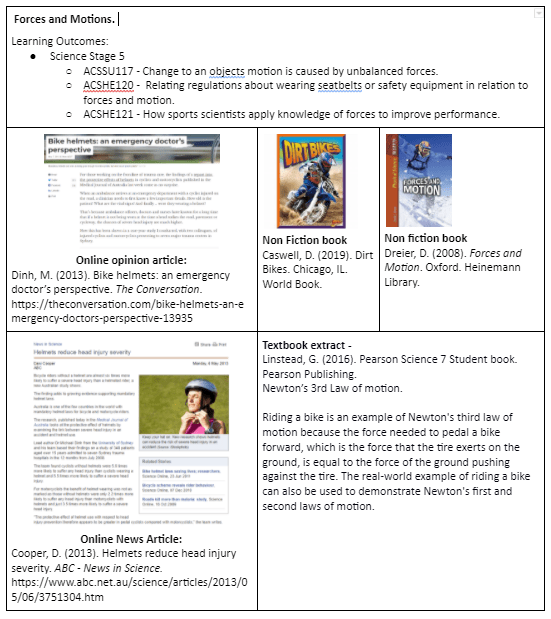

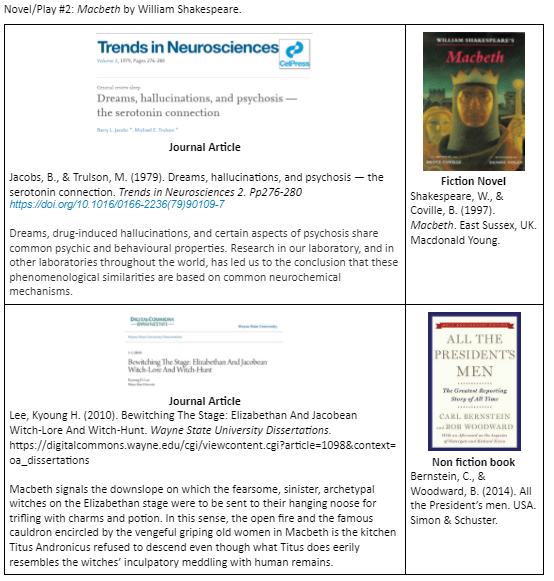

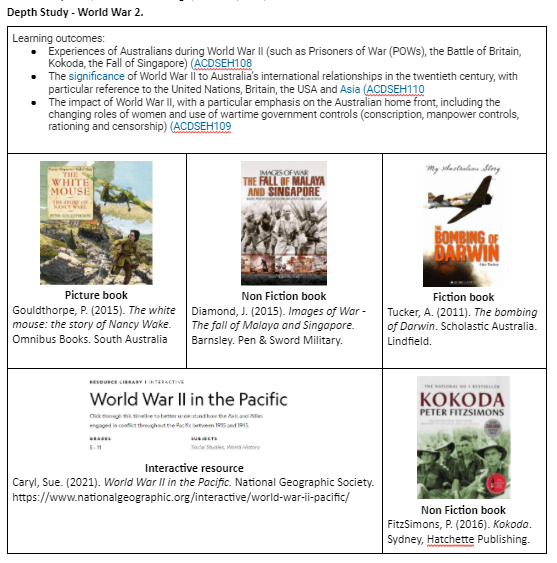

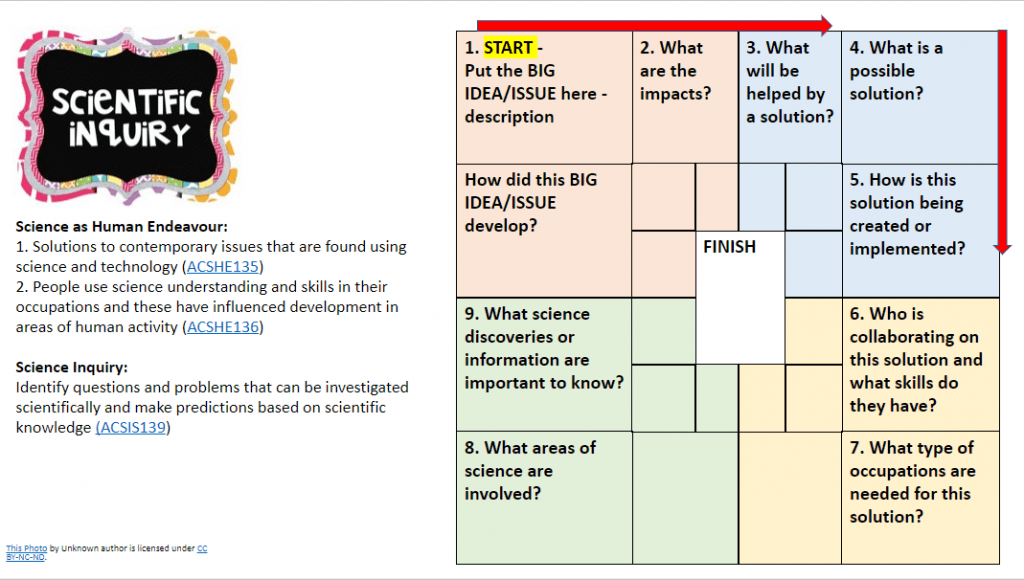

Teacher leaders often use servant leadership such as modelling good practice, sharing ideas, as well as coaching and collaborating with their peers to influence the pedagogical practices of their learning organisation (Fairman & Mackenzie, 2015, p68). Examples of such practice include working collaboratively with their colleagues to create inquiry units that develop important 21st century skills, or model literary learning through text sets, or literature circles as a viable alternative to textbook work, or share ideas of how to integrate emerging technologies such as AR and VR into their practice. Besides directly impacting pedagogical practice, teacher librarians are also tasked with being the information specialists of their school. This means that they are required to model and teach information literacy skills, provide a physical and digital learning space that is conducive to learning for all members of the community, and ensure the curriculum is resourced appropriately with access to print and digital material (ASLA & ALIA, 2004).

Support and limitations of teacher leadership in schools.

Even though it is widely acknowledged that classroom teachers have the greatest impact upon student learning and that collective teacher leadership is an effective method to implement school wide improvement, the capacity of a teacher leader is not being universally actualised (Cosenza, 2015, p.80; Lowery-Moore, Latimer & Villate, 2016, p.2). The efficacy of teacher leaders is often hampered from both the executive and from their colleagues through covert and overt behaviour. Some executives may view teacher leadership with disfavour as it infringes on their formal roles within a school (Isabu, 2017, p.149). Others may fail to endorse teacher leadership activity because they find the idea of pedagogical reform from the classroom unpalatable compared to reforms rolled out from the boardroom (Cosenza, 2015, p.81). Whereas, collegial reluctance is often due to resentment because an individual teacher leader’s strive for improving professional practice could increase the benchmark and change the status quo of acceptable teacher practice (Fairman & Mackenzie, 2015, p. 71).

Teacher leaders need the support from the executive leadership team in their school to succeed. Without their obvious support, the capacity of teacher leaders to thrive is limited. Executive leaders can overtly limit professional development opportunities to reduce the likelihood of teacher leader initiated reforms and covertly hinder their efficacy by exhibiting disinterest and apathy (Uribe-Florez, Al-Rawashdeh & Morales, 2014, p.11). Whilst disinterest from formal leaders limits the scope of a teacher leader to lead, apathy has significant implications towards teaching and learning in general. Organisations like schools will always take the path of least effort and if there is executive apathy, it can quickly stagnate school wide initiatives and limits a positive learning culture which directly impacts the value of learning for both students and teachers (Dinsdale, 2017, p. 43; Patel, 2019).

Conclusion

Teacher leaders are pivotal to school-wide improvement initiatives because they are able to effectively use the positive relationships that they have with their colleagues to improve professional practice. As teacher leaders most frequently use servant leadership to influence their colleagues, they are able to integrate and embed innovative teaching practices by leading others through explicit actions and through modelling good practice. Since teacher leaders can arise from any faculty across a learning organisation, they are able to impact change horizontally across the curriculum and as such, have a collective impact upon teaching and learning. However, the scope of teacher leadership is dependent on the actions of their leadership team. Effective teacher leaders thrive in schools with a positive learning culture and where they are empowered by their principal.

References:

AITSL. (2019). Certification of Highly Accomplished and Lead Teachers in Australia. National Policy Framework https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/national-policy-framework/certification-of-highly-accomplished-and-lead-teachers.pdf?sfvrsn=227fff3c_8

ALIA & ASLA. (2004). Standards of professional excellence for teacher librarians. Australian School Library Association. https://read.alia.org.au/alia-asla-standards-professional-excellence-teacher-librariansCosenza, M. (2015). Defining teacher leadership: Affirming the teacher leader model standards. Issues in Teacher Education 24(2). Pp79-99. EJ1090327.pdf (ed.gov)

Cherkowski, S. (2018). Positive teacher leadership: Building mindsets and capacity to grow wellbeing. International Journal of Teacher Leadership 9(1). EJ1182707.pdf (ed.gov)

De Nobile, J. (2018). Towards a theoretical model of middle leadership in schools. School Leadership & Management 38 (4). pp 395-416, DOI: 10.1080/13632434.2017.1411902

Dinsdale, R. (2017). The role of leaders in developing a positive culture. BU Journal of Graduate Studies in Education 9(1). Pp. 42-45. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1230431.pdf

Isabu, M. (2017). Causes and management of school related conflict. African Educational Research Journal 5(2). Pp.148-151. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1214170.pdf

Johnston, M. (2015). Distributed leadership theory for investigating teacher librarian leadership. School Libraries Worldwide 21 (2). doi: 10.14265.21.2.003

Lipscombe, K. Grice, C. Tindall-Ford, S., & DeNobile, J. (2020). Middle leading in Australian schools: professional standards, positions, and professional development. School Leadership & Management 40 (5) pp.406-424. DOI: 10.1080/13632434.2020.1731685

Lowery-Moore, H., Latimer, R., & Villate, V. (2016). The essence of teacher leadership: A phenomenological inquiry of professional growth. International Journal of Teacher Leadership 7(1). EJ1137503.pdf (ed.gov)

NSW Department of Education. (2020, February 12). Policy library: Library policy – schools. NSW Government. https://policies.education.nsw.gov.au/policy-library/policies/library-policy-schools

Patel, P. ( 1st April, 2019). Leadership – valuing dissonance. The Teacherist. https://theteacherist.com/2019/01/04/leadership-valuing-dissonance/

Riveros, A., Newton, P., & da Costa, J. (2013). From teachers to teacher leaders: A case study. International Journal of Teacher Leadership 4(1). EJ1137376.pdf (ed.gov)

Supovitz, J., D’Auria, D., & Spillane, J. (2019). Meaningful and sustainable school improvement with distributed leadership. CPRE Research Papers. University of Pennsylvania Scholarly Commons. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED597840.pdf

Uribe-Florez, L., Al-Rawashdeh, A., & Morales, S. (2014). Perceptions about teacher leadership: Do teacher leaders and administrators share a common ground? Journal of International Education and Leadership 4(1). EJ1136038.pdf (ed.gov)

Weisburg, H. K. & Walter, V.A. (2010). Being indispensable: A school librarian’s guide to becoming an invaluable leader. American Library Association.

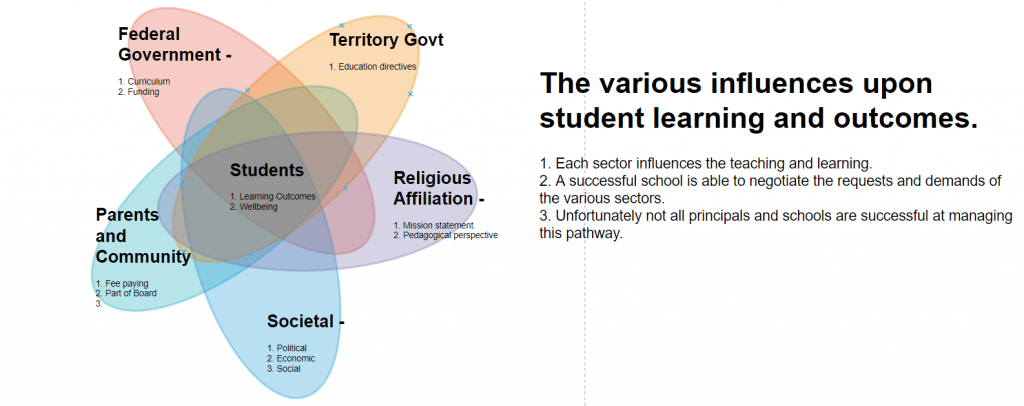

What influences a school’s decision making?

What influences a school’s decision making?