Tumisu / Pixabay – Languages matter

Language.

What language/s do you speak?

For many people the language they use is indicative of their nationality, culture and geographical placement. Language, especially a mother language, has the ability to motivate the individual to raise their strongest voice.

My life is a linguistic soap opera. Born in Mumbai, India, I completed the majority of my schooling in Brisbane before living sporadically along the eastern seaboard of Australia. Currently based in Canberra, I am a Mumbaikar by birth to Goan parents that never lived in Goa. By this convuluted history, I should possess the linguistic arsenal of Konkani, Marati, Hindi and English from my childhood years; and be reasonably fluent in Yugara, from my time spent in Brisbane and be commencing to learn Ngunnawal, the language of Canberra.

But no. Sadly I am only fluent in English, accented as it can be and possess a smattering of inappropriate words in a few other languages. Think more like a sailor and less like a teacher, if you get my drift!

I am also sure that I am not the only emigrant with this linguistic dilemma with a dismal knowledge of my native tongue. As new citizens, my parents so keen on assimilation that they discarded all linguistic connections to the motherland to ensure we settled in as quickly as possible.

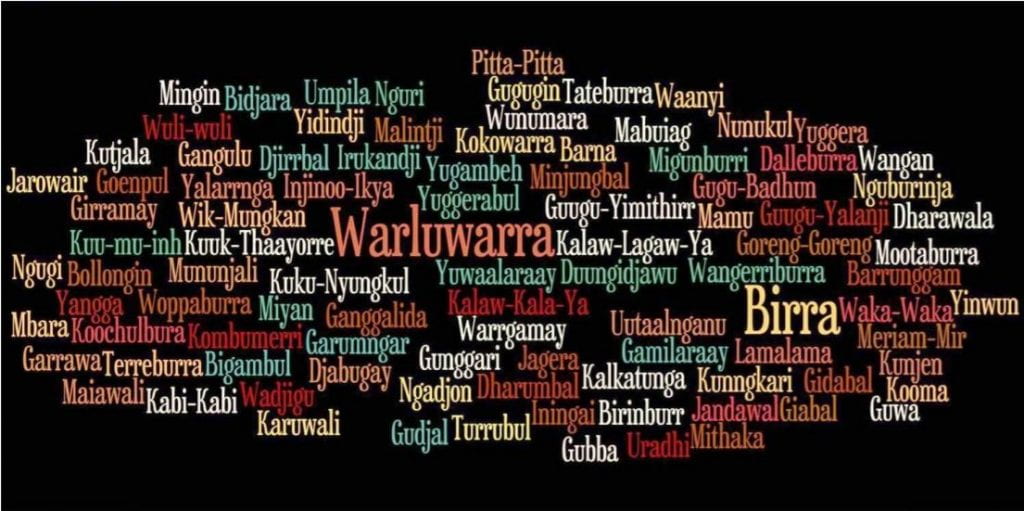

Unfortunately, this discarding of language has lead to feelings of inadequacy as an adult. Besides feeling like a ‘fake’, the saddest aspect of my own inadequacies of language is that I cannot teach my children their heritage. This death of language diversity can be attributed to numerous reasons, with emigration as mine. Other reasons include, political persecution, globalisation and civil war (Strochlic, 2018). In Australia alone, over 100 Aboriginal languages have disappeared since Philipsy and his ruffian filled boats docked in Sydney (Strochlic, 2018). You don’t have to try too hard to imagine why… do you?

Strochlic (2018) reminds us all that over 200 languages have become extinct since the end of WW2, with every fortnight another language dying a silent death. It is predicted that by the end of this century, another 90% will disappear. This loss is tragedy for current and future generations.

But all is not lost. Modern Hebrew, made a dramatic reappearance in the 18th century. Conversational Hebrew had all but disappeared in the 4th Century and was revived in the late 18th. As aspects of the language were preserved in copies of the Torah and Talmund across the world, the words and phrases within could then be extrapolated to frame conversational Hebrew (Bensadoun, 2015).

Another memorable reincarnation are the Egyptian hieroglyphs, which were decoded using the famous Rosetta stone. This stone was paramount in aiding academics in understanding the amazing wonders of that ancient empire. The stone helped construe the pictorial script into ancient Greek, which could then be further translated into modern day English (British Museum, 2017).

But what about languages with no written component? What will happen to those mother tongues? The speed in which languages disappear is heightened when they are only exist in an oral form as there is no documentation to ensure preservation. Communities with distinctive languages will become extinct and this death is a blot on society.

What can we do about it?

Well, there are several groups around the world that are seeking to preserve rare dialects and languages using wikis. These groups use available technology to record, store and transfer these conversations for preservation purposes. Noone (2015), additionally advocates the use of technology as a preservation tool to document and record languages for future generations. Other ICT tools such as Skype or Facetime, can be used by people to converse with greater ease even if separated by large distances. Language, like all other skills, becomes rusty with lack of use and regression is quite common when unused for extended periods. By using these tools, people all over the world can converse and practice their skills.

As teacher librarians, we can assist students and teachers access these audible resources. Libraries are no longer just archives for the storing of information. Instead, they are centres of ‘resourcing’ information. The same technology that permits us to document and preserve these languages also enables us to access and share them.

The State Library of Queensland has an impressive collation of Indigenous language resources on their webpage. They are working towards preserving and documenting the various dialects of the region and are drawing these word lists from their range of historical texts within the collection (SLQ, 2019b). I like the word lists. It is a simple way for me to learn some common use terms for myself and then share them with my children. SLQ also has another challenge on their portal called the ‘ Say G’day in an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander Language’. As 2019 is UNESCO’s Year of Indigenous Language, SLQ is challenging Queenslanders to use an Indigenous language to greet their mates in an effort to help raise awareness and promote Indigenous cultural awareness.

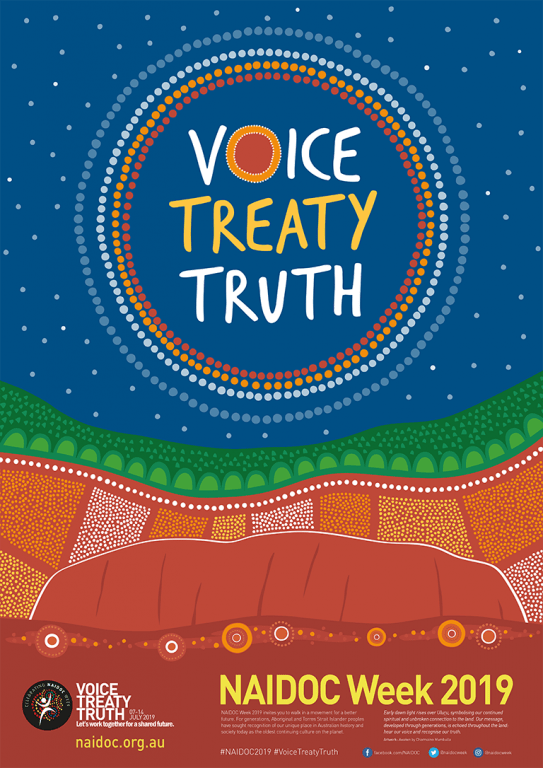

This sentiment is shared by this years NAIDOC’s them of “Voice, Treaty, Truth” as it places great emphasis on the importance of giving voice to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people of Australia. But as indigenous languages fade into the history pages, the voices that speak these languages are then also muted. There cannot be a treaty if voices are not heard. For voices to be heard and understood, we must understand that Australia is more than just English.

Whilst I do regret my inadequacy of mother tongue, I also regret not learning the language of land in which I stand on. It never crossed my mind to learn the local Indigenous dialect. That in itself is something I need to resolve as I forge my way through this M. Ed.

So I leave you with these greetings as I acknowledge that the language heritage and knowledge reside with the traditional owners, elders and custodians of the various nations. So from me to you,

G’day (English)

Galang nguruindhau (Turrbal)

Jingerri (Yugambeh)

Wunya (Yugara)

Deo boro dis dium (Konkani)

Namaskar (Marathi)

Nameste (Hindi)

REFERENCES

Bensadoun, D. (2010) History: Revival of the Hebrew language. Jerusalem Post. Retrieved from https://www.jpost.com/Jewish-World/Jewish-News/This-week-in-history-Revival-of-the-Hebrew-language

Brtish Museum (2017). Everything you wanted to know about the Rosetta stone. British Museum Blog post. Retrieved from https://blog.britishmuseum.org/everything-you-ever-wanted-to-know-about-the-rosetta-stone/

Crump, D. (2015) Aboriginal languages of the Greater Brisbane area. SLQ Blogs. Retrieved from http://blogs.slq.qld.gov.au/ilq/2015/03/16/aboriginal-languages-of-the-greater-brisbane-area/

Noone, Y. (2015) How technology is saving Indigenous languages. NITV. Retrieved from https://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/article/2015/11/11/how-technology-saving-indigenous-languages

Strochlic, N. (2018) The Race to Save the World’s Disappearing Languages. National Geographic. Retrieved from https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2018/04/saving-dying-disappearing-languages-wikitongues-culture/

State Library of Queensland (2019b), Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander word lists. Retrieved from https://www.slq.qld.gov.au/discover/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-cultures-and-stories/languages/word-lists

State Library of Queensland (2019), “Say G’day in an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander Language”. Retrieved from https://www.slq.qld.gov.au/sites/default/files/SLQ%20Say%20G%27day%20Wordlists%202019.pdf