geralt / Pixabay – The 3rd Millennium

The third millennium has clearly delineated a strong demarcation between people who are confident using digital technologies and those that are not.

Prensky (2001) attributed this confidence to the time frame in which people were born, and described that those that grew up with technology are designated ‘digital native’, and those who had to be introduced to technology as ‘digital immigrants’ (Prensky, 2001; Houston, 2011). Prensky (2001) stated that the modern student is digitally savvy because of their lifetime exposure to personal devices, the internet, and therefore will be highly competent using digital technologies in their personal, social and educational domains. He predicted that ‘digital natives’ would have increased intuitiveness and competence when using digital media, and teachers need to adapt their pedagogical practices to reflect this paradigm (Prensky, 2001; Houston, 2011).

Unfortunately reality is very different. Not all modern students are competent and adept with using digital technologies, and the use of the terms native and immigrant, as well as the assumption of proficiency, has led to frustration and a deep digital divide in the classroom and the greater community.

The terms digital ‘native’ and ‘immigrant’ itself are polemical.

Brown & Czerniewicz (2010) point out that by using these titles, society is polarising itself and categorising the former is fully adept using technology and the latter, a completely maladroit luddite. The terms can also be viewed to some people as offensive, as both the words natives and immigrants have negative connotations when considered in tandem with colonisation and immigration policies in the western world (Brown & Czerniewicz, 2011). Instead it seems more sensible that ICT competency be based and assessed upon ability and capability rather than age (Brown & Czerniewicz, 2011).

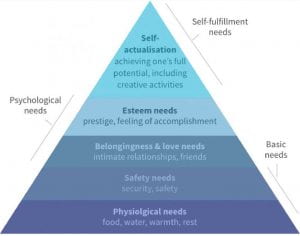

The most pertinent factor that these generic terms fail to acknowledge is the impact of privilege on ICT acuity.

The recent online learning experience clearly illustrated that it is the combination of these factors that affect ICT competence, not age or birth year (Brown & Czerniewicz, 2011).

From a personal viewpoint it appears that ICT ability and acuity is more comparable to a continuum rather than polar opposites. Individual and collective ability will vary depending on exposure to various software programs, frequency of use, access to devices and high speed internet in the home (Houston, 2011). It is simply ludicrous to assume familiarity with one program means virtuosity over all (Frawley, 2020).

For example, I would call myself competent when I use Windows or android devices, but am a complete tech-tard when it comes to Apple and Mac products because I am unfamiliar with them. I am fluent in Facebook, Instagram and Microsoft 365, but ignorant of TikTok, Snapchat and Minecraft. I may know the intricacies of a few programs and basics of many more, I am often completely unaware of any enhanced functionalities of how these programs can be used for social or educational purposes (Kirschner & De Bruyckere, 2017, p.136). By the same benchmark, I am comfortable with using many different forms of digital literature but would flounder if asked to create a hypertext digital narrative with embedded multimodal features. By Prensky’s parameters I am classified as a digital native as I was born after the onset of the information revolution, but since I don’t know how to play minecraft, lack a TikTok account and still listen to the radio, my year 7 students think the dinosaurs were around at my birth (Prensky, 2001)…. See… continuum.

This digital divide and inequality of access has proven to be a major issue for many families and households in Australia, as it is well known that teenagers who are not actively engaged in education, employment or training are most likely to be digitally disengaged (Helsper & Smirnova, 2019). This is because most educational institutions offer their students unlimited internet access through onsite wifi.

geralt / Pixabay – Schools and libraries provide equitable access to digital technologies.

The current Coronavirus pandemic and corresponding lock down restrictions have highlighted the disparity between that socio-economic status and residential postcodes and corresponding impact on a person’s ICT competency and educational success (DIIS, 2016; Thomas et al., 2018). The shutdown of schools, libraries and other educational institutions have shown that people who live in lower SES communities, or in rural and remote areas, recent immigrants and refugees, as well as First Nations peoples are significantly more disadvantaged when it comes to access and ICT competency (DIIS, 2016; Thomas et al., 2018). Reasons cited include insufficient funds to purchase personal devices and access to high speed internet, living in shared housing or remote areas, loss of employment and lack of a fixed address (DIIS, 2016; Thomas et al., 2018).

geralt / Pixabay – Coronavirus closures.

Community leaders and social organisations are very concerned with further disenfranchisement arising from the Coronavirus pandemic and the corresponding closures of schools, libraries, governments and social organisations shopfronts (Alam & Imran, 2015). This means that socially disadvantaged individuals are even further inconvenienced by their lack of ICT knowledge and access (Alam & Imran, 2015). For young people, these closures have extended ramifications as they are conscious of their lack of access and often end up feeling marginalised and excluded, due to their inability to have an active participation in a digital society (Helsper & Smirnova, 2019). (For more information on inequalities in digital interactions click here!)

The term digital native is now considered obsolete by most reputable educational professionals (Frawley, 2017). Brown & Czerniewicz (2010) clearly indicate that age is not an indicator of ICT acuity but rather access to devices and the internet is what defines digital adroitness. Instead of using the terms ‘native’ and ‘immigrant’, Brown & Czerniewicz (2010) advocate the terms ‘elite’ and ‘stranger’, as it seems financial security is a greater indicator of digital acuity than age .

Digitally elite students have unlimited out of school access to ICT through personal devices, high speed internet, and electricity, whereas digital strangers have limited access to ICT and the internet once they are no longer on their educational or professional site (Brown & Czerniewicz, 2011). These digital strangers are often of lower socio-economic status, lack digital technology at home and rely on public services such as libraries to access the digital world (Alam & Imran, 2015; Baker, 2019). This digital disadvantage can often be exacerbated by a lack of English as they are unable to participate in community run computer courses (Alam & Imran, 2015). The combination of lack of access and an inability to communicate can increase social exclusion, inhibit full participation in society as well as lead to further marginalisation and division in society (Alam & Imran, 2015).

In conclusion – the terms digital native and immigrant are no longer valid. Digital acuity and competence is instead based upon a person’s access to digital technologies and high speed internet in their residence, which is directly correlated to financial stability and urban living. By assuming someone’s digital ability based upon their age, teachers and educators are disadvantaging their students and reducing their learning potential.

Stay tuned for Round 2 – The Classroom Divide.

REFERENCES:

Alam, K. & Imran, S. (2015). The digital divide and social inclusion among refugee migrants; A case in regional Australia. Information Technology & People, 28(2), pp.344-365. Retrieved from https://eprints.usq.edu.au/27373/1/Alam_Imran_ITP_v28n2_AV.pdf

Baker, E. (2019). Digital access divide grows in disadvantaged communities. ABC News. Retrieved from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-08-12/digital-access-divide-grows-among-disadvantaged-tasmanians/11402218

Coughlan, S. (2020). Digital poverty in schools where few have laptops. BBC News – Family and Education. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/education-52399589

De Bruyckere, P. (2019). Myth busting: children are digital natives. ResearchEd News. [Blog]. Retrieved from https://researched.org.uk/myth-busting-children-are-digital-natives/

Department of Industry, Innovation and Science. (2016). Australia’s digital economy update. Retrieved from https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2016/05/apo-nid66202-1210631.pdf

Duffy, C. (2020). Coronavirus opens up Australia’s digital divide with many school students left behind. ABC News. Retrieved from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-05-12/coronavirus-covid19-remote-learning-students-digital-divide/12234454

Education Magazine. (2020). What is the digital divide and how is it impacting the education sector? The Education Magazine [blog]. Retrieved from https://www.theeducationmagazine.com/word-art/digital-divide-impacting-education-sector/

Frawley, J. (2017). The myth of the digital native. Teaching @ Sydney [blog]. University of Sydney. Retrieved from https://educational-innovation.sydney.edu.au/teaching@sydney/digital-native-myth/

Kang, C. (2016). Bridging the digital divide that leaves schoolchildren behind. New York Times – Technology. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/23/technology/fcc-internet-access-school.html?_r=0

Kirschner, P., & De Bruyckere, P. (2017). The myths of the digital native and the multitasker. Teaching and Teacher Education 67, p.135-142

Helsper & Smirnova. (2020). Chapter 9. Youth inequalities in digital interactions and well being. Education 21st Century Children: Emotional Wellbeing in the Digital Age. OECD iLibrary. Retrieved from https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/d0dd54a9-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/d0dd54a9-en

Holt, S. (2018). 6 Practical strategies for teaching across the digital divide. NEO BLOG. Retrieved from https://blog.neolms.com/6-practical-strategies-teaching-across-digital-divide/

Houston, C. (2011). Digital Books for Digital Natives. Children & Libraries: The Journal of the Association for Library Service to Children, 9(3), 39–42.

McMahon, M. (2014). Ensuring the development of digital literacy in higher education curricula. ECU Publications. Edith Cowan University. Retrieved from https://ro.ecu.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1835&context=ecuworkspost2013

Miller, H. (2017). The myth of the digital native generation. E-Learning Inside. Retrieved from https://news.elearninginside.com/myth-digital-native-generation/

Online Typing.org. (2020). Average typing speed (WPM)[blog]. Retrieved from https://onlinetyping.org/blog/average-typing-speed.php

Pontefract, D. (2017). The fallacy of digital natives. Pontefract Group [Blog]. Retrieved from https://www.danpontefract.com/the-fallacy-of-digital-natives/

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants. Marckprensky.com. Retrieved from https://marcprensky.com/writing/Prensky%20-%20Digital%20Natives,%20Digital%20Immigrants%20-%20Part1.pdf

Steele, C. (2018). 5 ways the digital divide effects education. Digital Divide Council. Retrieved from http://www.digitaldividecouncil.com/digital-divide-effects-on-education/

Thomas, J., Barraket, J., Wilson, C., Cook, K., Louie, Y., Holcombe-James, I., Ewing, S., and MacDonald, T. (2018). Measuring Australia’s Digital Divide: The Australian Digital Inclusion Index 2018. RMIT University, Melbourne, DOI: https://doi.org/10.25916/5b594e4475a00

References:

References: