How will my learning from this subject inform my practice to build my leadership capacity?

Ability to thrive

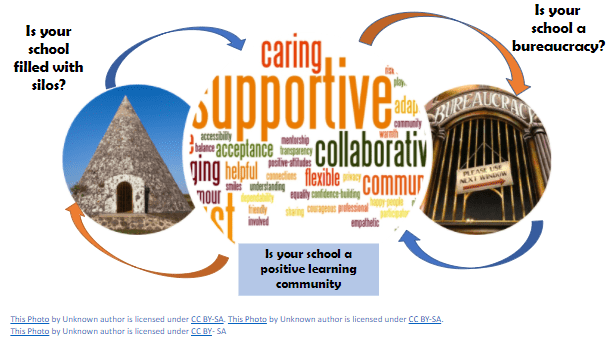

The teacher librarian’s (TL) efficacy is dependent on the principal’s leadership, school culture and their own leadership capacity (Templeton, 2021c). Under the right circumstances, TLs can thrive, exert their prowess and become innovators of pedagogy and technology (ASLA & ALIA, 2004). However, if the stars are misaligned or the school is a quagmire of silos and entrenched bureaucracy, TLs can become stifled, bored, ignored or irrelevant. Therefore it is essential that TLs identify the circumstances that impact their ability tobecome future focused leaders.

Leadership

I had assumed leadership was managerial in nature, occurred at the top and directives went down the chain of command (Templeton, 2021b). Therefore I was astounded that transformational leadership supports middle school leaders, teacher librarians and teacher leaders implementing changes (Templeton, 2021c; Templeton, 2021d; Templeton, 2021e). As the modules progressed, I learned that TLs thrive best under transformation leadership, as this style cultivates a positive learning culture, promotes team building, advocates professional growth and builds leadership capacity in others so that they can be instruments of change in their departments (Longwell-McKean, 2012, p. 24).

This video connects leadership to culture.

Learning Culture

As teachers we all know that a positive learning culture is essential for optimum student learning outcomes, but there seems to be uncertainty if teachers are included in this learning paradigm (AITSL, 2017). Ambivalent or negative learning cultures directly impact implementation of school wide practices, however, TLs are able to make the library space a positive environment by supporting learning in their community through instituting professional development, modelling best practice, provision of resources and mentoring (Bourne, 2021; Templeton, 2021a; Sharman, 2021).

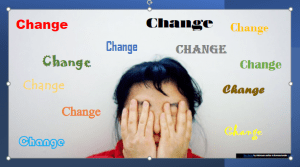

Change Fatigue

The single most important fact I gained from this course is that rapidly mandated change fails because there is lack of consultation, insufficient processing and integration time, lack of education and inadequate practical support for teachers (Armstrong, 2021b; Cherkowski, 2018; Dilkes et al., 2014). For change to succeed, it must be perceived to be valuable, effectively implemented and practical support during transition freely offered (Kim et al., 2019). Australian teachers are in a change crisis because the introduction of the national curriculum, standardised testing, shift to constructivism and digital learning has led to extreme change (Dilkes et al., 2014; Stroud, 2017). As a result, teachers often manifest disinterest or disinclination because of their reluctance to experiment with new ideas or technologies stemming from feelings of being undervalued, fear of failure, reprisals and even the transitory nature of those changes (Riveros et al., 2013, p.10). Change fatigue is a valid concern and needs to be effectively mitigated before any school wide changes are expected to succeed.

Professional Guidance

TLs often work independently and many lack clear expectations of their position and the moral confidence to pursue leadership roles (De Nobile, 2018, p.401; Lipscombe et al., 2020, p.419).

TLs often work independently and many lack clear expectations of their position and the moral confidence to pursue leadership roles (De Nobile, 2018, p.401; Lipscombe et al., 2020, p.419).

Whilst many TLs use the standards set by ASLA & ALIA (2004) and (AITSL) 2017 to frame their practice, it is recommended that AITSL’s Australian Professional Standard for Principals (2014) is used to future practice and develop leadership capacity (Lipscombe et al., 2020, p.412). However, many TLs may find these standards daunting, but it is important to remember that leadership is the use of social influence to exert others to achieve a goal or vision and is not restricted to just the top of an organisation.

Future Focus

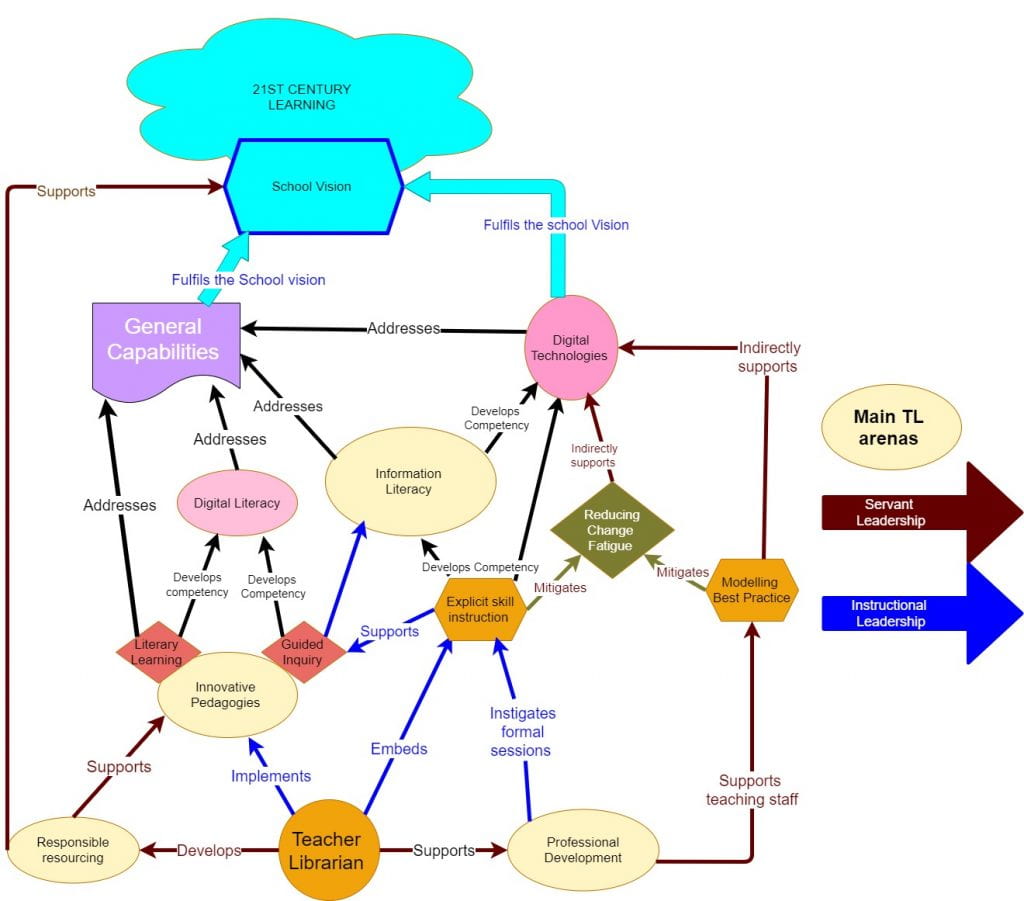

The future focused TL has four main arenas that support the school vision, responsible resourcing, innovative pedagogies, formal and informal professional development opportunities to mitigate change fatigue, and development of information literacy (Armstrong, 2021a; Bourne, 2021; Stiles, 2021). By combining practical support with coaching or mentoring, the TL is able to slowly change the school’s groundswell. It is through these arenas of focus that TLs can support their colleagues and the principal in achieving the vision of active and engaged citizens who can problem solve effectively, work collaboratively as well as think critically and creatively (MCEETYA, 2008).

The future focused TL has four main arenas that support the school vision, responsible resourcing, innovative pedagogies, formal and informal professional development opportunities to mitigate change fatigue, and development of information literacy (Armstrong, 2021a; Bourne, 2021; Stiles, 2021). By combining practical support with coaching or mentoring, the TL is able to slowly change the school’s groundswell. It is through these arenas of focus that TLs can support their colleagues and the principal in achieving the vision of active and engaged citizens who can problem solve effectively, work collaboratively as well as think critically and creatively (MCEETYA, 2008).

References:

AITSL. (2017). Australian professional standards for teachers. Education Services Australia. australian-professional-standards-for-teachers.pdf (aitsl.edu.au)

Armstrong, K. (2021a, March 14). Module 3 ICT integration. [Online discussion comment]. ETL 504 Discussion Forums. CSU – Interact 2

Armstrong, K. (2021b, May 4). Stress in schools: Is it optional? Musings and Meanderings. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/karenjarmstrong/category/etl-504/

AITSL. (2014). Australian professional standard for principals and the leadership profiles. Education Services Australia. https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/national-policy-framework/australian-professional-standard-for-principals.pdf?sfvrsn=c07eff3c_6

ASLA & ALIA. (2004). Australian professional standards for teacher librarians. ALIA. https://read.alia.org.au/alia-asla-standards-professional-excellence-teacher-librarian

Bourne, H. (2021a, May 22). Module 6: Week 11/12 – AITSL professional learning. ETL 504 Discussion Forums. CSU – Interact 2

Cherkowski, S. (2018). Positive teacher leadership: Building mindsets and capacities to grow wellbeing. International Journal of Teacher Leadership, 9(1). EJ1182707.pdf (ed.gov)

De Nobile, J. (2018). Towards a theoretical model of middle leadership in schools. School Leadership & Management 38(4). pp 395-416, DOI: 10.1080/13632434.2017.1411902

Dilkes, J., Cunningham, C., & Gray, J. (2014). The new Australian curriculum, teachers and change fatigue. Australian Journal of Teacher Education. 39(11). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1047053.pdf

Kim, S., Raza, M., & Seidman, E. (2019). Improving 21st-century teaching skills: The key to effective 21st-century learners. Research In Comparative And International Education, 14(1), 99-117. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745499919829214

Lipscombe, K., Grice, C., Tindall-Ford, S., & DeNobile, J. (2020). Middle leading in Australian schools: Professional standards, positions, and professional development. School Leadership & Management 40(5) pp.406-424. DOI: 10.1080/13632434.2020.1731685

Longwell-McKean, P.(2012). Restructuring leadership for 21st century schools: How transformational leadership and trust cultivate teacher leadership. UC San Diego. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6746s4p9

MCEETYA. (2008). Melbourne declaration on educational goals for young Australians. Curriculum Corporation. Australia. http://www.curriculum.edu.au/verve/_resources/national_declaration_on_the_educational_goals_for_young_australians.pdf

Riveros, A., Newton, P., & da Costa, J. (2013). From teachers to teacher leaders: A case study. International Journal of Teacher Leadership 4(1). EJ1137376.pdf (ed.gov)

Stroud, G. (2017). Why do teachers leave? ABC News – Opinion. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-02-04/why-do-teachers-leave/8234054

Templeton, T. (2021a, February 28). Module 1 – culture. ETL 504 Discussion Forums. CSU – Interact 2

Templeton, T. (2021b, March 1). Leadership – The beginning of ETL504. Trish’s Trek into Bookspace.

Templeton, T. (2021c, March 14). Leading from the middle – Teacher Librarian as a middle leader at school. Trish’s Trek into Bookspace.

Templeton, T. (2021d, March 6). Transformational leadership. Trish’s Trek into Bookspace.

Templeton, T. (2021e, May 7). Teacher leaders. Trish’s Trek into Bookspace.

Sharman, S. (2021, March 22). Module 3 ICT integration. ETL 504 Discussion Forums. CSU – Interact 2

Stiles, Y. (2021, April 27). Module 4.3-4.3. ETL 504 Discussion Forums. CSU – Interact 2 .