Category: ETL503 Resourcing the Curriculum

Collection Development and My Future

[Reflection on ETL503 Modules 5, 6 & 7]

My two top thoughts following these modules is that there are a lot of issues that could arise from hoarding, weeding and censorship and thus clear policies and procedures are imperative.

As it is very likely that, should I be fortunate enough to get employed as a TL, I will have to write a collection development policy, I am worried I might struggle with it. I will certainly be the first to put up my hand and ask my colleagues and library network for assistance!

What I know about myself is that I struggle looking at an example of someone else’s work as a means to produce my own. I struggled to look at colleague’s work when preparing my accreditation, I struggle modifying other people’s teaching and learning units of work to suit my class or context…and critical analysis of the St Bede’s CDP, a school context in which I have very little understanding, has been very challenging. So it is unlikely that I will take much stock in using a different school’s CDP as a guide…

Alternatively, I prefer to look at professional industry recommended templates, which I’ve found more helpful personally.

As to the future of school libraries and trained school librarians, being an information literacy specialist, curriculum expert and keen marketing amateur is going to play a big part in our success. I am hopeful that I can make a difference.

Creating a Collaborative Climate – The Triple C’s

[Reflection of ETL401 & ETL503 (The TL Role in Collaboration)] (*addendum 16 September 2019 for ETL504)

I think I’ve been pretty clear in my stance on the impact of temporary and casual work environments to the collaborative climate. If not, then I suppose I should mention here how much it wears away at collaboration to have individuals fighting for the renewals of their contracts: completely and utterly.

I think I’ve been pretty clear in my stance on the impact of temporary and casual work environments to the collaborative climate. If not, then I suppose I should mention here how much it wears away at collaboration to have individuals fighting for the renewals of their contracts: completely and utterly.

The casualisation of the teaching workforce, particularly in my personal working context, is not something I am able to change as an individual. Helping create a collaborative climate (despite the political climate) however, I can try to change.

Before we jump head first into collaborating with classroom teachers on an inquiry unit of work, let’s take a step back. I mean, yes we want to design and implement inquiry learning and literature programs and we certainly want to help embed digital formats. But we need to confront the elephant in the room in stead of simply shrugging our shoulders and saying ‘some teachers just don’t want to collaborate.’

I would argue that some teachers haven’t had positive collaborative experiences in the past (experiencing – much like a lot of students must experience – forced compliance rather than collaboration) or some teachers expect judgement in disguise rather than collaboration.

We ran into this in a school where we were trying to roll out Quality Teaching Rounds (QTR). We surveyed the staff to identify their concerns and these were the results:

Q. Why do we have to? (Comfort Zones: Not comfortable being watched / observed / critiqued; Doubt ‘teamwork’ capabilities; Criteria for involvement unclear; Feel pressured to do it).

A. (summarised) Be the change you wish to see in the world. Also, the NSW DET require a colleague observe you once a year so it might as well have a clear structure and limits and offer real improvement to your teaching.

Q. What’s the benefit? (Is there follow up; What do ‘we’ get out of it; Evidence of benefits; How does it improve the school; How valuable is it versus mentoring which we do already).

A. (shown QTR training slides proving benefits based on research)

Q. How could we possibly do it? (Logistics / Resources: What types of lessons have to be observed, eg 1:1, whole class, small group; Time off class; Casuals; Time required for prep work outside school hours).

A. (Thankfully, the principal had budgeted for the resources and did not have a set idea of what sort of lessons were required for observation).

The QTR team did our best with the resources and research provided by the QT Framework training to answer these concerns in a specially allocated staff meeting. We then surveyed the staff to determine their level of interest, which was about 70% in favour, and a few other teachers joined the second ‘Quality Teaching Round.’

Furthermore, in this process and in the readings for ETL401 Module 4, it occurred to me that an aspect of (primary) teaching that impacts collaboration is an ingrained and embedded culture of isolation. A teacher, predominantly alone in a room of students (or a Teacher Librarian on their own in the library) cannot effectively collaborate with other teachers as well as someone working in an office filled with cubicles or a group of engineers on a building site.

Another aspect of collaboration are the social norms of either Australian culture, or the culture of a town or city, or the culture of a school context. An immigrant and possible ASD person myself, I struggle with social norms on a daily basis.

I am also struck by the massive gap in the expectations of our TL role as collaborators, where we are expected to just jump in there and collaborate with teaching and learning programs with people who don’t know anything about us and of whom we also know very little…it is a bit ‘chicken before the egg’!

The OECD-UNICEF (2016) Education Working paper’s ‘dimensions of learning’ for organisation transformation touches on this (developing and sharing a student centred vision, having a culture of support for staff learning opportunities, promoting team collaborative professional development and embedding systems that support it, establishing daily expectations or ‘culture’ of inquiry, innovation and exploration–including staff in leadership roles, and learning with and from larger learning systems outside of the school context or direct governing body).

Logistically though, what does this look like? I love the idea of the ATSI community’s ‘yarning circle’. But how do I help create a ‘yarning circle’ or gathering spot where we can get to know each other and our contexts and socialise professionally? How do I help draw people out of their shells and into the safe environment of a collaborative climate?

Creating a Collaborative Climate (The triple C’s):

I can’t do it alone. There are things the executive must do to help improve the collaborative climate and things that they will need from me as well. However, once I’ve developed a rapport with the principal by helping them achieve their ideas, I will liaise with the principal to allow for time and budget amounts to be determined and allocated to enable some or all of the following of MY (8) ideas for creating a collaborative environment each year as follows:

- In an allocated staff meeting or staff development day, we sit in a ‘yarning circle’ and discuss ourselves, our school and any concerns openly and freely, using the ideas from this link as a guide: ATSI community’s ‘yarning circle’.

- Everyone completes the School Context Survey (draft version also in links on the right side of this blog) either collaboratively or on their own in time provided.

- Everyone takes the VIA Character Survey and shares their top 5 / 10 character traits for the year (they can change slightly each year).

- Everyone completes the Philosophy of Teaching Survey (draft version in links also on the right side of this blog). My own philosophy of Teaching has been updated for 2019 using the survey questions and can be used as a guide.

- A photo of the teacher is either created or supplied with their permission (see #7 below for format ideas) using the Photo Permission Form Template created by the American Library Association (or similar).

- The results of the school context, VIA, and philosophy surveys can then be sent electronically to the TL to be added to a electronic photo of the teacher(s) (with their permission), &/or collated and presented on an intranet or school website (which, unfortunately I do not have at present as I am not attached to a particular school).

- I even have ideas (I have a marketing background, don’t forget!) on what the end result would look like and have pinned these ideas onto my Teacher Spotlight Pinterest board. (This board could also, theoretically, be made available for all of the school staff to edit).

- And finally, (and this is where it gets a bit heavy), introduce Quality Teaching Rounds (in which I am an advocate and trained to deliver) to the school at least once a year if not twice, depending on budget and time allowances.

From here, collaborating on programming and teaching collaborative inquiry units are a walk in the park.

*16 September 2019 ETL504 addendum: See the template link on the left of the blog for initiating a collaborative inquiry unit with a classroom teacher Created by Christy Roe, based on suggestions from Carr, J. (Ed.), (2008) p.13-14; 28; 39; and Bishop, (2011) p.7.

*16 September 2019 ETL504 addendum: See the template link on the left of the blog for initiating a collaborative inquiry unit with a classroom teacher Created by Christy Roe, based on suggestions from Carr, J. (Ed.), (2008) p.13-14; 28; 39; and Bishop, (2011) p.7.

WHEW! Its a big task. I hope I’m up to the challenge!

References:

Bishop, K. (2011). Connecting libraries with classrooms. Retrieved from ProQuest Ebook Central.

Carr, J. (Ed.). (2008). Leadership for excellence: Insights of the national school library media program of the year award winners. Retrieved from iG Library.

OECD-UNICEF. (2016). What makes a school a learning organisation? A guide for policy makers, school leaders and teachers. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/education/school/school-learning-organisation.pdf

Be Smart! Copy Right! & Creative Commons!

[Reflections of ETL503 Module 4 Legal and Ethical Issues of Collections]

Thoughts that occurred to me while reading about Copyright laws, the SmartCopying assistance website and Creative Commons:

- The NSW Department of Education (DET) are said to ‘own’ the ‘intellectual property rights’ to my yearly teaching and learning program documents, which I have created either: at home or at school or at a training facility and either: off my own back or because of training the DET have provided for me. We must also attribute or reference items that we get from our schools (or the DET) or items ‘created as part of your duties’ because this applies to the Crown Copyright laws. But does this mean that the ‘crown’ own the material and that we must therefore leave a copy of our programs at the schools in which we’re employed (by the crown)? In my LGA, schools have interpreted these laws to mean that they must collect a printed version of my yearly teaching and learning program and store it on sight, because – in the view of the executives of the LGA schools – the DET ‘own’ the rights to the contents of my program. Do they really? Did I sign something giving over my copyright protection when I joined the DET as an employee? Are the executives in my LGA misinterpreting the DET’s policy on Copyright and infringing on my rights as the author of the program? Where then does this impact on me when I do my program completely electronically on the cloud, e.g. do the executives have the right to force me to print it or share it permanently with them electronically, so that they can store a copy indefinitely? Doesn’t this bring into issue the rule that copies of resources in my program cannot be stored indefinitely? This is, on the whole, a problematic policy…to which, I simply reply: “no. “

- While copyright infringement is obviously hard to police in the classroom, it can be easily monitored by online applications that search things like library catalogues for ‘pirated’ material. So, it might not be a good idea for schools to hoard digital/cloud collections of teacher’s work or programs, which might have been pirated?

- Programming is also becoming very collaborative. Some teams of teachers even share their program freely to the public on the Internet or on social networking platforms such as the string of FaceBook groups: ‘On Butterfly Wings English’ / Mathematics / Science / Creative Arts / etc. I understand that the work must be co-referenced if it was created collaboratively. However, if work is shared to the greater teaching community for use educationally, how is this to be referenced or does it have to be referenced according to Copyright law? Is it even legal to share it so broadly given that the employer presumably ‘owns’ the rights to the work?

- Teachers are not meant to be profiting from the work that they’ve created while employed with the DET. This is meant to stop teachers from ‘selling’ their programs or resources that they’ve either created or obtained for profit, as they ‘belong’ to the DET. Is this because of the Statutory Text and Artistic Licence Permit that the DET holds as teachers selling possibly copyrighted materials would null the DET’s yearly permit?

- Regarding the music that schools in my LGA generally upload from iTunes or YouTube for end of year concerts…these events are open to the public and as a performance of the music to the public, should we make sure we have Copyright permission – or is this covered by the Statutory Licenses? When I checked the DET website, I am still unclear if the yearly licences for playing films, TV or radio for non-educational purposes are paid for by the DET or the schools themselves.

- Is the Australian Copyright law’s lack of a requirement to register copyright and lack of requirement to list the copyright on a piece of work, the reason why copyright infringement is rife in Australian society? Would it be more rife if the laws were more strict? Who has more copyright infringement, the USA or Australia? How would we ever be able to research this and really know when it is usually an underground / blackmarket issue?

- Is lack of transparency or knowledge regarding the special licenses granted to schools enabling schools to teach students (inadvertently) that they, by default, don’t have to worry about Copyright?

- If all websites need to be accessible by people who have disabilities, (Flynn 2016) shouldn’t alternate modes of communication be mandatory based on the needs of the people in every school context? What about ‘bridging the gap’ for ATSI communities? How effective is a school with an entirely digital form of communication, when the majority of the community are illiterate or too poverty stricken to afford access to a computer or internet facilities? I am keen for Australia to take the lead in website accessibility as a social justice issue rather than waiting for Americans to pull their fingers out and make a change. An American by birth myself, I am horrified that their greatest solution to the injustice is to teach their students with disabilities to be advocates for change for themselves. While I appreciate that students should be taught to self-advocate, this is a bit of a ‘flick pass’ on behalf of educators who should be advocates for their students as well (IFLA 2012).

- This is a great PowerPoint for schools to use to help educate students (and teachers) on the use of Creative Commons: Creative Commons in the the classroom.

- Some important links that all TL need to keep bookmarked from SmartCopying.com (National Copyright Unit n.d.):

- ‘Educational Licences in Schools and TAFE’;

- Text Works & Fair Dealing/& ‘reasonable portion;

- ‘Playing Films, Television and Radio in Schools’/Film, Video/DVD /‘Playing films for non-educational purposes‘;

- Internet and Websites;

- Performing and Communicating Music in Schools;

- Copyright Implications of Content Management Systems: Schools;

- Assisting children with disabilities

References

Coates, J. (2013). Creative Commons in the the classroom. [slideshare]. Retrieved from http://www.slideshare.net/Jessicacoates/creative-commons-in-the-classroom-2013

Flynn, N. (2016, December 16). Australian web accessibility laws and policies. cielo 24. Retrieved from https://cielo24.com/2016/12/australian-web-accessibility-laws-and-policies/

Gibbs, J. (2014, January 26). 1. How copyright works [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/WWIV8ZmFhvM

International Federation of Library Associations. (2012). IFLA code of ethics for librarians and other information workers. Retrieved from http://www.ifla.org/files/assets/faife/publications/IFLA%20Code%20of%20Ethics%20-%20Long_0.pdf

Palmer, Z. B., & Palmer, R. H. (2018). Legal and ethical implications of website accessibility. Business and Professional Communication Quarterly, 81(4), 399-420. Retrieved from https://journals-sagepub-com.ezproxy.csu.edu.au/doi/pdf/10.1177/2329490618802418

National Copyright Unit. (n.d.). Smartcopying. Retrieved from http://www.smartcopying.edu.au/

“This budget is too tight, could I try the next size up?”

(Reflection on ETL503 Module 3.1 Funding the Collection):

- “Should teacher librarians have the responsibility of submitting a budget proposal to fund the library collection to the school’s senior management and/or the school community? Or should such proposals come from a wider group such as a school library committee?

- Is it preferable that the funding for the school library collection be distributed to teachers and departments so they have the power to determine what will be added to the library collection?” (Giovenco 2019).

Well, here we go again. I thought when I got out of marketing (where I was given a budget amount and had to account for all expenditures within that budget) that I had seen the last of tight budgets. Tsk Tsk. Welcome to the world of being a Teacher Librarian!

- The responsibility for budgeting for the library is possibly best done collaboratively with the teacher librarian and the school executive and possibly the school’s P&C (who also have access to funds). As per the CSU Module (Giovenco 2019) a TL should be a budget collaborator, steward and thinker. Moreover, having never been in charge of creating a budget, I would be hesitant to take on a budget on my own and would be reliant on someone with expertise to help me.

- I have not mentioned classroom teachers intentionally. Should we collaborate with teachers about resources they might need? Yes of course. Should teachers have a say in the budget? Perhaps, yet I am leaning towards no. After all, why would teachers have a say in the budget for the library when they don’t have a say in any way what-so-ever in any other area of the budget? Teachers in some schools are given ‘classroom budgets’ and I think that spending that money is enough for them to worry about. Just do a Google search for ‘What should I spend my classroom budget on?’ and you will get 55,600,000 results. As soon as you ask for input, the assumption will be that what is asked for will be received and that is dangerous ground. Better to survey the teachers and ask what sort of resources they were thinking of or if they had any ideas and leave the budgeting to an executive committee that includes the TL.

In order to have a balanced (or at least one that fits) budget and a fully resourced curriculum I believe it is important to start with a clear policy in the Collection Development Plan.

There are loads of resources on how to do this (Such as Lamb & Johnson 2012, & Australian Library and Information Association (ALIA) Schools et al 2017, pp.20-25) and I intend to make good use of them!

Good Idea: Let’s make sure that a ‘perfect fit’ or balanced budget remains the goal as opposed to being in surplus…we don’t want to behave like or be perceived as politicians do we? Well, speaking for myself, I certainly do not.

Good Idea: Let’s make sure that a ‘perfect fit’ or balanced budget remains the goal as opposed to being in surplus…we don’t want to behave like or be perceived as politicians do we? Well, speaking for myself, I certainly do not.

To show the ‘balance’ (or presumably the lack thereof) I most certainly agree to having a section for the library in the School Annual Report in the format suggested by the school or using a template such as the one below:

References

ALIA Schools & Victorian Catholic Teacher Librarians. (2017). Budgeting policies and procedures. In A manual for developing policies and procedures in Australian school library resource centres. Retrieved from https://www.alia.org.au/groups/alia-schools

Giovenco, G. (2019). Budgeting for a balanced collection. In ETL503: Module 3: Accession and Acquisition [Subject module]. Retrieved from Charles Sturt University website: https://interact2.csu.edu.au/webapps/blackboard/content/listContent.jsp?course_id=_42383_1&content_id=_2636378_1

Lamb, A. & Johnson, H.L. (2012). Program administration: Budget management. The School Library Media Specialist. Retrieved from http://eduscapes.com/sms/administration/budget.html

Censorship creates hackers, curation creates thinkers?

(Reflection on ETL503 Module 2.6)

When I first started this course, my thoughts on information was that it was important to me that everyone have access to all information (Moody 2005), individual limitations such as disability, geography, financial capability/internet access not-withstanding, (as this is a more complex social justice set of issues). I believed information was not something that any person or corporation should own.

When I first started this course, my thoughts on information was that it was important to me that everyone have access to all information (Moody 2005), individual limitations such as disability, geography, financial capability/internet access not-withstanding, (as this is a more complex social justice set of issues). I believed information was not something that any person or corporation should own.

In that sense, I suppose I have the heart of a hacker. Not the sort of hacker who wants to steal a person’s private information in order to rob them, I’m not talking about being a person who commits cyber crime. I am more thinking along the lines of civil liberties and protesting the rise of stringent ‘intellectual property law.’ (Coleman 2012).

Thoughts: in fact, can anyone really own information? … Similarly to the indigenous community beliefs: Does anyone really ‘own’ land: Aren’t people simply custodians of information in varying degrees?

However, as I am studying the Teacher Librarian as information specialist role, I am fine-tuning my beliefs and perceptions. I can now see how curating and resource selection can benefit students (and society) by narrowing down the playing field to a more manageable and relevant space. I am understanding my own motivations better!

Censorship, a historically relevant concept, is motivated by either overt, covert (Moody 2005, pp.145) control, social engineering and seeking proof of weaknesses in information of a whole text – negating any strengths that the information might contain (Ashiem 1953, pp. 63).

Curation (aka resource or information ‘selection’) is motivated by democratically believing in an information seeker’s ability to think, providing others with the freedom to think and read, the freedom to value information within the context in which it was written despite any perceived ‘flaws’ within the minutia of the information (Ashiem 1953, pp. 63, & Lukenbill 2007 pp.28).

When pursuing the path of ‘selection’ of resources or ‘curation’ of resources, TL’s or school resource selectors must then demonstrate ongoing and diligent and consciousness of their (possibly overt or covert) bias and motivations as well as the (possibly overt or covert) bias and motivations of other stakeholders (including ‘community standards’ arguments which seek to take content out of context or limit the range of information available to information seekers, for the purpose of censorship) for selecting or de-selecting resources in order to ensure that they do not cross the line from curation into censorship (Jenkinson 2002 pp. 23, & Moody 2005, pp. 142).

Moreover, rather than be motivated to select or deselect resources based on ‘community standards’, TLs need to focus on providing a range of information and views (Moody 2005, pp. 143) as per Australian ‘industry standards’ such as those provided by ACARA, NESA or AITSL and appropriately curating the library collection to suit the curriculum and the point of need in our individual contexts (Moody 2005, pp. 146, & Lukenbill 2007 pp 26).

Furthermore, if the school library has a formal Collection Development Plan and / or procedure for resource selection/curation/censorship policy section or survey questionnaire for challenges or complaints, then it will offer some protection from external or internal bias and censorship (Jacobson 2016, & ALA 2016).

References

ALA (2016), “Challenge Support” Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/tools/challengesupport

Asheim, L. (1953). Not censorship but selection. Wilson Library Bulletin, 28, 63-67. Retrieved from: http://www.ala.org/advocacy/intfreedom/censorshipfirstamendmentissues/notcensorship

Coleman, E. G. (2012). Coding freedom: The ethics and aesthetics of hacking. Princeton University Press.

Jacobson, L. (2016). Unnatural selection. School Library Journal, 62(10), 20. Retrieved from https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.csu.edu.au/docview/1825615756?accountid=10344

Jenkinson, D. (2002). Selection and censorship: It’s simple arithmetic. School libraries in Canada, 2(4), 22. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.csu.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=lih&AN=7277053&site=ehost-live

Lukenbill, W.B. (2007). Censorship: What do school library specialists really know? School Library Media Research, 10. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/aasl/sites/ala.org.aasl/files/content/aaslpubsandjournals/slr/vol10/SLMR_Censorship_V10.pdf

(2005) Covert censorship in libraries: a discussion paper, The Australian Library Journal, 54:2, 138-147, DOI: 10.1080/00049670.2005.10721741

Fiction vs Non-Fiction – Want vs Need – Guilt vs Joy

[Reflection on ETL503 Module 2]

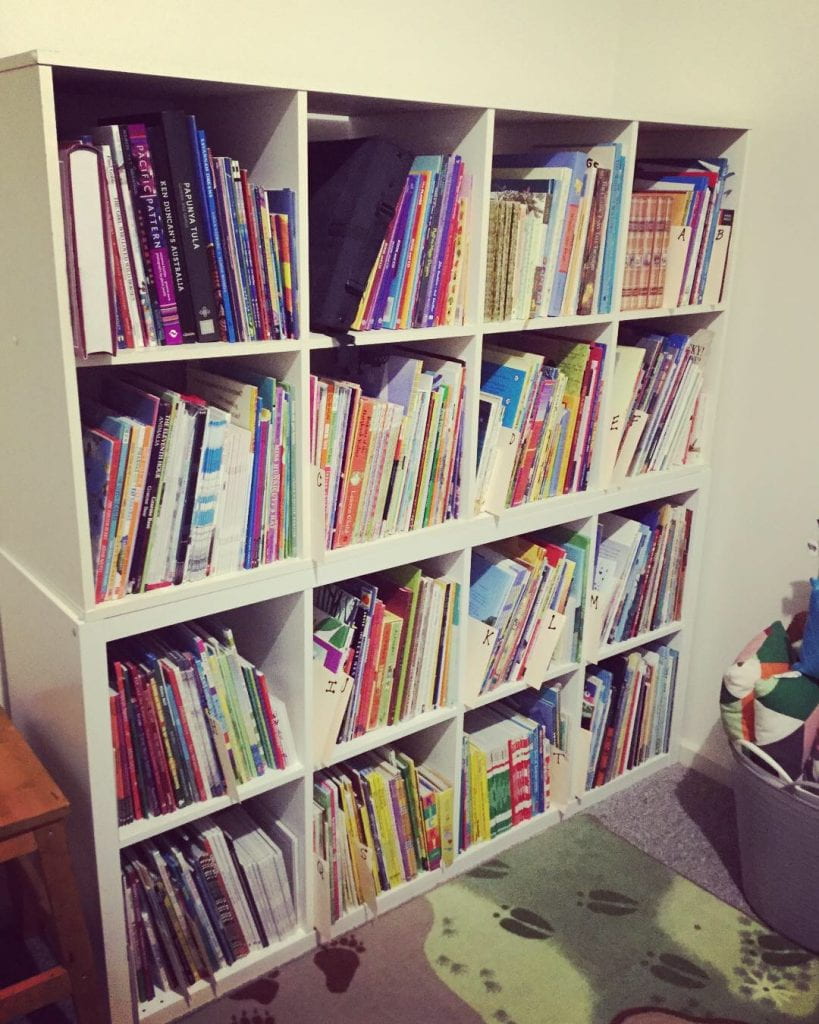

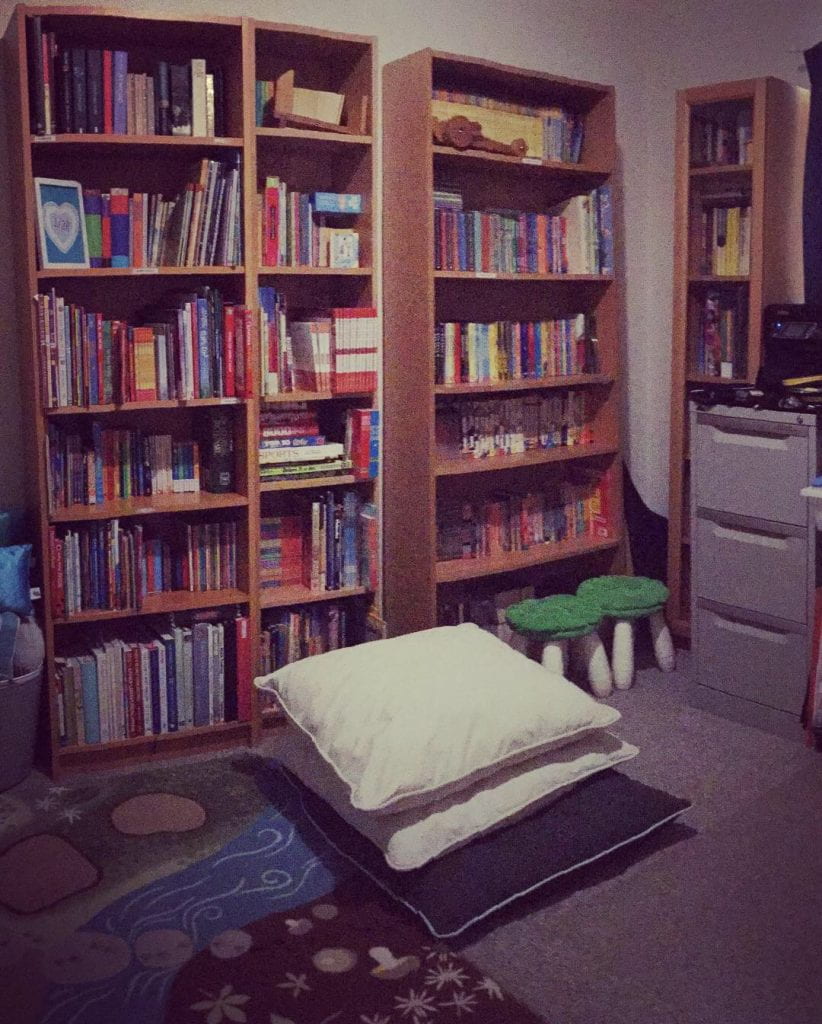

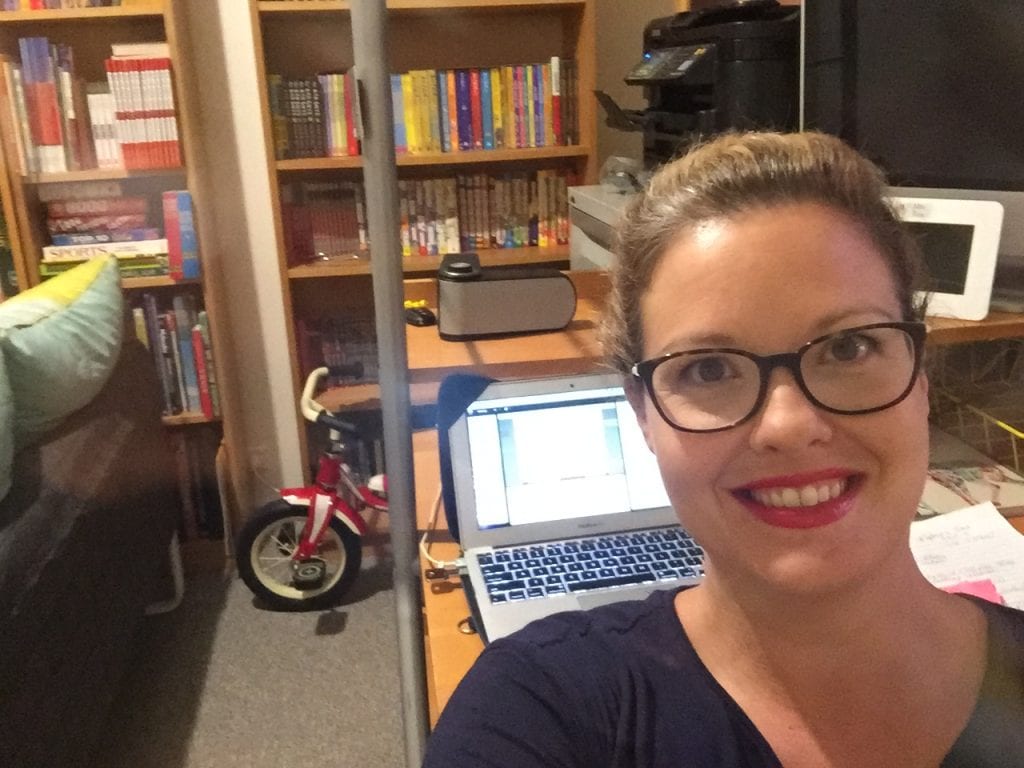

Recently I weeded (deselected) my personal library. (Most of the books in the attached images had lived their lives previously in either mine or my husband’s classrooms, which had to be packed up at the start of this year and put into storage as neither of us are ‘on class.’)

I had a box of romance novels from my late teens early 20’s and a collection of crime fiction from my early 20’s and 30’s that I thought I would want to keep forever but in fact, following moving house twice, they simply took up storage space. [IN FACT, fair disclosure: don’t be misled by how organised it looks now–the room pictured was previously a toy room and the books were in a different room packed floor to ceiling with boxes!]

In accordance with Marie Kondo’s (2019) KonMari method (originally a book, now a series on Netflix), many books did not ‘bring me joy.’ It was liberating to get rid of them–except for my collection of Sue Grafton mass market books, as her A-Z series hasn’t finished yet, let’s not get crazy! [Sidebar: Marie doesn’t say you have to get rid of any particular number of books. Relax.]

I decided to weed out some of our student fiction books. I kept some ‘classics’ and all books with matching CDs or automated reader capabilities (hugely popular). I kept all books by known authors and those that were part of a series (breaking a series or getting rid of a series hurts my heart – was I feeling guilted into keeping them? Possibly). But a lot of the books that I got in Scholastic book fair mixed author ‘packs’ or at Scholastic ‘box of books for $40’ warehouse sales got the axe with no regrets.

Asking myself, ‘does this book bring me joy?’ the main cull of books also came from my non-fiction shelves. My husband (also an educator) and I managed take about 10 boxes of books to Lifeline. Our reasoning: the information inside them was available online and a lot of the information in the books that we owned had gone out of date.

However, when we took the books to Lifeline, a parent from one of our local schools wanted all of them. In our area, most families are living below the poverty line and don’t have access to a lot of books and many don’t have a home computer. And, to be fair, these books have been read so often in our classrooms that they were falling to bits. The parent took them to the local ‘toy library’ facility where they will hopefully be loved and utilised as a means to teach young children initial literacy skills and surround them with literature.

So I’ve been reading the modules for ETL503 again and I’m asking myself now, which do students in our area need/want/prefer: Fiction or Non-fiction? What is the difference between a need vs want and does it really matter when resourcing the curriculum? Why do teachers (and TLs) keep resources, is it because of guilt or joy?

Fiction vs Non-fiction: Which one students prefer depends on the students themselves and what they are doing in any given point in time. To pit one type of text structure against the other is comparing apples and oranges. In my classrooms, students select non-fiction if they are only allowed a short amount of time for reading. If they are given more time, they select a trending fiction text. If they are new readers, they select storybooks we’ve studied in class (and invariably want to read them out loud to someone – preferably an adult!) If they are sharing a book with a friend, they go for the Joke books, Search and Finds, or books like the Guinness Book of World Records.

Sometimes, as students get older, they might think fiction books are for babies (or maybe they find them too romantic or disconnected from their lives –anyone tried to study Romeo & Juliet in high school? Was that fun for the majority of the boys in the class…?) and they might prefer non-fiction for a time. My husband and his younger sister profess to have never enjoyed reading fiction texts for pleasure, however, they have always enjoyed reading biographies or “non-fiction personal narratives” (Mosle, 2012).

In fact, the question of fiction vs non-fiction is the wrong question.

A better question would be: What is the library’s (and in fact, the school’s) main goals? What are students trying to achieve and what kind of resource would help them meet their personal and educational goals?

Are students reading for pleasure without an intentional or identifiable goal other than pleasure, and what do they identify as pleasurable–fact or fiction? Are students reading for obtaining information or skills that will enable them to achieve a particular goal or pursue a particular interest in their educational journey, and what will help them meet these goals–fact or fiction?

Need vs Want: Adults can be so presumptuous when deciding what children need vs want! Why does it have to be one or the other? Have you ever been in a school where they prohibit children from playing ‘shooting’ games using sticks or lego built ‘guns’? This is part of their ‘kinder culture’ and social development and isn’t indicative of future violence as adults (Alexander 2015). Have you ever worked in a setting where Barbie dolls weren’t allowed because of the presumed negative body image ideas that these dolls might encourage?

The lines between reality and imagination are very blurred for young children. There is, theoretically, no harm in this behaviour because adults have been using it to their advantage for centuries: by reading texts about fictional characters, children learn societal norms and preferred moral behaviours (Sekeres 2009). Children connect with fictional characters in a similar fashion to how they connect with real people and have a sub-culture that is entirely their own.

“Notions of childhood are more complex, more pathologized (sic) and more alien to adults who educate and parent” (Steinberg 2018, pp.2).

In this world of trying to ascertain what students at a given context NEED, it is important to recognise our own bias and preconceived notions before we acquire resources.

When looking at stages of development and trying to identify student NEED, we must not be fooled into thinking that these are a fixed, unchangeable means with which to view our students. When matched with an incongruent benchmark, students of today will be falsely judged as not ‘making the grade’ and could in turn have low expectations of themselves (Steinberg 2018). Students who believe they’ve ‘measured up’ to adult expectations may believe it due to their ability when in fact their success is more closely related to race and privilege (Steinberg 2018, pp.4).

Students can tell us what they WANT and that will simply have to take precedence over what we as educators think they NEED.

Once students have been asked and their voice has been heard, we can pursue our own agendas, as identified by Kimmel (2014):

“The school library collection serves the mission, goals, and objectives of the school, the school system, and the state. Our first consideration should be our learners— both present and future. The clientele of the school library and the curricula should inform identification of the ideal collection. Curricula, including local, state, and national standards, are important considerations. Identifying gaps also requires knowledge of the current collection. A needs assessment, therefore, develops a vision of the ideal collection needed to meet the needs of students and the mission of the school, and then measures this ideal against data about the current collection.” (Kimmel 2014, pp. 25).

Guilt vs Joy: Let’s not keep resources simply because we feel guilty getting rid of them. Let’s not be hoarders…has anyone else gone into a school library and thought: Does anyone actually read any of these old books? Why is this still here? What is that pile? What is in this filing cabinet? Why are there 10 old radios on this shelf? Do we even have computers that could read all of these floppy discs any more? I have been into a library like this, and it was traumatising.

We can’t keep things just because we think someone MIGHT need it in the future. We need to recognise what WILL be used in the future and what HAS been used in the recent past.

When weeding a collection, including equipment, Kimmel (pp. 67-68, 2014) recommends we ask ourselves and survey as required: In our school context and given our goals and curriculum needs, is (any particular resource): in good condition and / or appealing? Is it current? Is it relevant to stakeholders?

When I am a TL and/or next time I move house, I will continue to consider my collection as it relates to my learning in this course…possibly hanging on to those non-fiction texts a bit tighter. Until then, on to the next module!

References

Alexander, S. (2015). Superheros and Weapon Plan for Fun and Learning. MyECE Experts. Retrieved from: https://www.myece.org.nz/activities-for-childhood-learning/254-superhero-play-weapon-gun

Kimmel, S. C.. (2014). Developing Collections to Empower Learners, American Library Association. Retrieved from: ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/csuau/detail.action?docID=1687658.

Kondo, M. (2019) KonMari. Retrieved from: https://konmari.com/

National Library of NZ. (2014). Non-fiction. National Library of New Zealand Services to Schools. Retrieved from: https://web.archive.org/web/20160729150727/http://schools.natlib.govt.nz/creating-readers/genres-and-read-alouds/non-fiction

Mosle, S. (2012, November 22). What should children read? [Blog post]. Opinionator: The New York Times. Retrieved from: https://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/11/22/what-should-children-read/?_r=0

Sekeres, D. C. (2009). The market child and branded fiction: A synergism of children’s literature, consumer culture, and new literacies. Reading Research Quarterly, 44(4), 399-414. Retrieved from: http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.csu.edu.au/stable/25655466?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

Steinberg, S. R. (2018). Kinderculture : The corporate construction of childhood. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com

Why ‘Teach Starter’ Makes Me Cringe

[Reflection on ETL503 Module 2.2 The Balanced Collection]

Okay, I get it. I’m a fish out of water in my current local government area (LGA) of schools. As a (recent) day to day casual relief teacher, I am increasingly finding myself filling in for ‘New Scheme’ temps who are fresh from University. As a seasoned educator who has worked in upwards of 15 schools, over 12 years, in a variety of full time, part time, contract and casual positions, I should be be helping teachers who are starting out in the profession.

When I first started teaching, the more seasoned educators helped me too. They guided me on how to teach grammar when my generation was left behind in an era where grammar wasn’t explicitly taught. They gave me behaviour management ideas and resources for successfully delivering guided reading literacy groups. They came in to my class and taught lessons while I observed. They suggested training courses and organised my attendance. They gave me formats for planning and in some team situations, whole units of work complete with required resources already printed and ready to go. They did these things because they wanted me to succeed in the goal we all shared: improved student outcomes.

Now, in my current LGA context where the number of temporary teaching positions outweigh the number of permanent or seasoned teachers, sharing isn’t done willingly. Competition for positions is the number one game. As a casual (this year) I am happy to not be an active part of that. However, it still has an impact on me when I want to help but I’m seen as either a ‘substandard’ teacher filling in for more capable teachers or competition for contracts for next year. Or maybe people just don’t want to share because they are afraid of what I might say…

I say all of this because I am struggling to understand why the hell everyone here is so obsessed with using Teach Starter (2019) (https://www.teachstarter.com/) to program for their classes?

Teach Starter (2019), in my view is for that little gap in the unit of work where the resource is outdated or unavailable, for finding more diverse resources to differentiate a program, or perhaps for people who don’t know how to program or create or collaborate to create units of work or resources. It is for schools who don’t already have scope and sequence documents. In 2019, what schools don’t have programs, units of work or scope and sequence documents? I am utterly horrified.

And heaven help me if I, a mere casual, ask to see someone’s teaching and learning program. You’d think I’d asked to see the inside of their bedside table. Seriously, if you can’t stand behind your program proudly you need to lift your game.

Another issue that I have with Teach Starter (2019) is that it costs money to be a member and access the (very basic and ‘cutesy’) resources that any teacher worth their salt could whip up in five minutes.

Fine if the school have purchased it for the teachers to use based on collaboration and discussion with all stakeholders and the program fulfils a context need. Not fine if the teachers have to pay for access themselves. Not fine for casuals (like myself) who are left a sentence or two as a teaching and learning program for the day: e.g. “go into Teach Starter and teach the powerpoint on ‘communication-then and now.'” Oh my god, please kill me now.

Furthermore, just because the resources are digital, doesn’t mean the delivery isn’t the same as ‘chalk and talk.’ (For a resource to truly be a useful digital learning tool, it needs to offer more than just a digital version of a chalkboard!)

So let’s program effectively hey? Let’s start with the point of need for our individual students based on suggested syllabus outcomes, meet as a team to discuss a scope and sequence, share ideas and resources for the lessons and make sure those lessons meet the Quality Teaching Framework standards (Collins, 2017). Let’s ensure that the lessons can then be delivered effectively no matter what teacher turns up on the day, by making our programs easily accessible and truly collaborative.

If Teach Starter (2019) is a part of that, then so be it. So long as we keep in mind that programs full of resources and websites or applications full of resources shouldn’t be the only avenue that we use for programming.

In the meantime, I think we, Teachers and Teacher Librarians et al, need to get out of Teach Starter (2019) and stop starting at resources, and instead we need to start at the point of need for our students. Perhaps the only way for look for this to occur is to first get improved executive leadership skills in our LGA…or maybe fewer ‘New Schemers’…Now there’s an idea.

References

Collins, L. 2017, ‘Quality Teaching in Our Schools’, Scan, 36(4), pp. 29-33. Retrieved from: https://education.nsw.gov.au/teaching-and-learning/professional-learning/scan/past-issues/vol-36,-2017/quality-teaching-in-our-schools

Teach Starter (2019). Teach Starter Pty Ltd. Retrieved from: https://www.teachstarter.com/

Musings of an Apprentice Information Specialist

Following my ‘pass’ on my Discussion Essay (Assessment 2) for Introduction to Teacher Librarianship (ETL401) I had another look through the forum posts for Module 2 from my colleagues this week and I wrote notes of my thoughts as I went along:

INFORMATION: A school context must come to an agreed understanding to a definition of, opinions of, and methods for seeking and absorbing information. Thus, we will have a better understanding of what is an ‘information specialist’ or ‘information literacy’ or ‘information (insert word here)’.

MULTI-LITERACIES: Back in my UWS studies in 2003-2006, we didn’t learn much about how to implement Guided Reading groups using PM Readers (ugh, I despise this method of teaching anyway) but we did a fair amount of study around ‘multi-literacies’ (Lilly & Green 2004 p.99 & 118, Worthington & Carruthers 2003 p.12, Arthur 2001, & Barratt-Pugh & Rohl 2000 p. 198-201).

[Sidebar: In fact, in my NSW Department of Education (DET) job interview in 2006, I was asked how I would implement my English program and when I answered academically, with my knowledge of ‘multi-literacies,’ I failed the interview and was told to do another practicum in a primary school (although that was not officially a requirement of the DET) in order to ‘pass’ my interview and be granted a teacher number. The head of the panel, a high-school principal, was worried that I wouldn’t implement the traditional Australian primary school English content and would create a generation of illiterate students, I suppose. Thankfully, I did as she asked and got the job easily the second time around…interesting how ‘multi-literacies’ has come full circle in the form of ‘information literacy’ as well…but I digress.]

GOING GLOBAL: Information has become more global, as has our society, with the introduction of digital technologies and the ‘world wide web.’ This means that we, as Teachers and Teacher librarians must be more flexible with our students as global citizens, acknowledging and integrating: multiple languages, multiple cultural norms, multiple methods of information seeking, multiple methods of information absorption (aka ‘learning’), multiple learning styles (that change depending on an individual person’s context in any given moment in their lives) and multiple ability levels.

Is information that is globally available, much like the fancy car that a rich family buy their inexperienced teenager, less valued? If it comes too easily will it get taken for granted and generally end in a car crash?

Is information that is globally available, much like the fancy car that a rich family buy their inexperienced teenager, less valued? If it comes too easily will it get taken for granted and generally end in a car crash?

SOCIAL MEDIA: The global network has also seen the creation of ‘social media’ and ‘wiki’ spaces. This impacts on people’s learning because, while social media is an excellent tool for engagement and delivery of information (linked to the research and marketing analytics done by corporations on how to reach target audiences–particularly children as per Veltri, et al 2016), social media is a weak platform in which to apply knowledge to every day reality. It is a sub-reality. A false replication of actual society with real, living and breathing humans and human interactions.

This is evident in any situation where someone makes an educated statement on a social media platform and is then hit with a barrage of abusive comments. People on social media platforms go on to social media platforms in order to be ‘social’–they aren’t there to be educated and aren’t open to absorb information, particularly if they have to work for it or if said information puts them out of their comfort zones and into a learning pit.

NAVEL GAZING: I wonder if the prevalence or demand for self expression on social media has been  born from the American talk show and self-help movement? Much like these movements who focus ‘in rather than out,’ (Murray 2015) could social media confuse the lines of what is a therapy tool, versus valuable information or accurately tested and researched knowledge?

born from the American talk show and self-help movement? Much like these movements who focus ‘in rather than out,’ (Murray 2015) could social media confuse the lines of what is a therapy tool, versus valuable information or accurately tested and researched knowledge?

ACADEMIC SOCIAL MEDIA: When we blend academia with social media, do we then, in turn, blur lines of authenticity for students? Why are some blogs academic and some mere musings? Is the blurring of academic information being part of the deep web versus readily available on the internet a clever way of engaging students in academia, embracing the method of delivery preferred by 21st century learners?

EASY TO FIND OVERLOAD VS RESTRICTED ACCESS DEEP WEB: Both are problematic. Historically, libraries have suffered the weight of hoarding and politicalisation of information. Encyclopaedia Britannica have a great topic page on their website (El-Abbadi 2019) about the Library of Alexandria which details how the Royal library and its ‘daughter’ library the Serapeum were destroyed by fire and war.

Great swaths of information have been destroyed in the past, and in today’s global information network, we are drowning in misinformation, irrelevant information, and less connection to information.

We are slightly more organised on the deep web, which is less susceptible to misinformation, but more likely to segregate and discriminate against users, particularly to society’s lower classes.

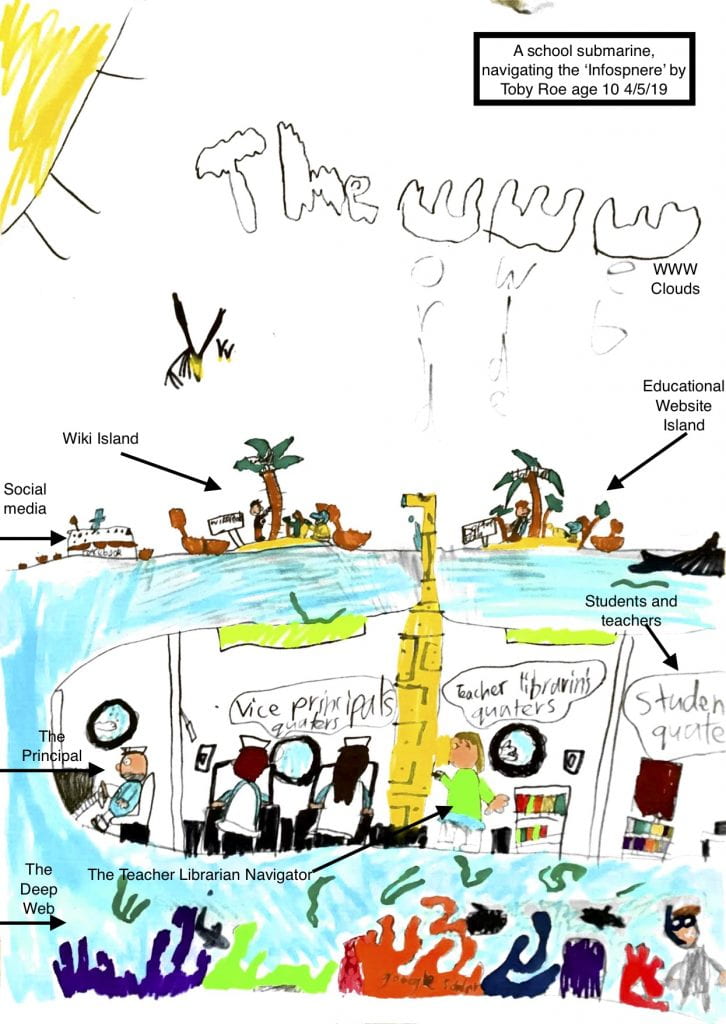

THE TL ROLE: In order to be valued as TL who are information specialists, we are the navigators and we need tools like telescopes, compasses and maps to help the ship navigate the ‘infosphere’ (Floridi 2007). We must safely navigate towards islands of internet information and cruise ships of social media. We must safely navigate below the water, helping the ship find and understand the underwater volcanoes and creatures of information.

TL’s need to:

- remember how to use digital technologies

- but to still keep in mind that using social media for work purposes is like working while on holiday, particularly for some teachers and teacher librarians who are suffering from stress or burnout, or who are trying to stabilise their work/life balance and

- we must strive to enable students to go through the stages of the Learning Cycle,

- use evidence-based practice,

- be aware of theories and pedagogies that we have been using as teachers, such as Multiple Intelligences and/or the Berry Street Educational Model (BSEM) for trauma informed practice or Quality Teaching Rounds, and

- work collaboratively with all stakeholders, much like the crew of a submarine!

Teacher Librarians need to be the navigators of the (school) submarine. The principal and executives are the captain and first mates. The teachers are the crew and the kids, the families are the passengers. The submarine needs everyone to work together in order to be able to navigate the information sea above the water, including the political breezes and cultural water currents, the social media cruise ships and the various modes of information islands. It also needs to be able to safely navigate below the sea in the deep web with all of the volcanic deep web databases, applications and sea creatures that lurk about in the darkness.

References:

Arthur, L. Young children as critical consumers. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy. Oct 2001. v24. i3. p.182(14).

Barratt-Pugh, C. & Rohl, M. (2000). Literacy learning in the early years. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

El-Abbadi, M. (2019). Encyclopaedia Brittanica. Retrieved from www.brittanica.com/topic/library-of-alexandria

Floridi, L. (2007). A look into the future impact of ICT on our lives. The Information Society, 23, 59-64. CSU Library.

Lilly, E. & Green, C. (2004). Linking Home and School Literacies. Developing partnerships with families through children’s literature. NJ: Pealson.

(2015) Notes to self: the visual culture of selfies in the age of social media. Consumption Markets & Culture, 18:6, 490-516, DOI: 10.1080/10253866.2015.1052967

Worthington, M. & Carruthers, E. (2003). Children’s Mathematics: Making Marks, Making Meaning. London: Paul Chapman Publishing.

Veltri, G. & Lupiáñez-Villanueva, F. & Gaskell, G. & Theben, A. & Folkvord, F. & Bonatti, L. & Bogliacino, F. & Fernández, L. & Codagnone, C. (2016). (Radboud University) Study on the impact of marketing through social media, online games and mobile applications on children’s behaviour. Published by Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.1.2576.7280.

Beautiful Doesn’t Mean New

(Reflection on ETL503 Resourcing the Curriculum Module 2)

When ‘resourcing the curriculum,’ as a teacher librarian I will need to remember lots of information as mentioned in the module. I will also need to remember two things:

- Beautiful doesn’t always mean new, (see image) and

- Sometimes patron/student needs outweigh their wants. (*See below)

1. New things aren’t always the best things. My grandmother’s recipe for chicken and dumplings far outweighs any new dishes that my mother or my aunts dreamt up for our yearly Thanksgiving or Christmas feasts. Old buildings using engineers, fine brickwork, stone masonry or intricate carpentry far outweigh cardboard or plastic construction-particularly in times of natural disasters like earthquakes.

Should digital resources replace physical resources? If new is perceived as better, then will Artificial Intelligence replace teachers? Guilherme (2019) goes into this with a powerful depth. We are facilitators, but we are also teachers. We are providers of information but we also teach the skills to interpret the information and utilise it in life.

2. A key factor in ‘resourcing the curriculum’ is that it reinforces the concept of ‘information as a commodity.’ As much as we’d like libraries and information to be free, the fact is that neither are without cost. (Whether that cost is paid by taxes or individuals is a political debate for another day.)

In terms of ‘information as a commodity,’ this has some powerful landmines. The idea that information can have ownership has led to a strong community of hackers whose primary function is to provide information that someone or a corporation has deemed ‘a commodity’ and opportunity for profit.

For librarians, ‘information as a commodity’ is also full of landmines. We are adults, we are educated, we have a job to facilitate the education of students. We are also, gendered, cultural, geographical, and loaded with our own personal string of internal bias.

*Does the student voice of their needs or wants, outweigh what society (and the teacher librarian) view as student needs or wants or vice versa?

I am having a lot of colliding thoughts about ‘engaging learners’ and fulfilling ‘needs’ of the learners &/or the school community and ‘who has the final say’ in resourcing the curriculum.

I say colliding because I have taught at so many different schools (South West Sydney, Far West, casually and through temporary engagement, RFF, classroom teaching, job share, etc) and can see a common lack of consideration for sociocultural context of students for programming and planning. If programming and planning were a building, the foundation is the sociocultural context. Without a sound knowledge of the school’s foundation, the building / educational program will crumble and resourcing the curriculum becomes moot. The library starts to fail or becomes irrelevant. The funding decreases. The principal sees no point in allocating a qualified TL. People start throwing around the idea of getting rid of a library altogether. In the distance: sirens.

Yesterday I worked at a geographically isolated and drought affected primary school with a large number of students from very low SES, high evidence of trauma (large ATSI population, witnesses of or suffers of domestic violence, neglect, alcohol / drug / physical / mental / emotional abuse / deaths in the family), higher than state average numbers of students with diagnosed and undiagnosed disabilities (including lead affected disabilities due to historical mining practises) and the students in this area are, overall, not meeting state expectations based on NAPLAN results. In my area, there are a statistically higher numbers of these things in all of the schools but in this particular school, the statistics are more visible.

As a result, most of the students are coming to school to feel or express love. (See Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs as explained by McCloud, 2018 in the reference list below). They have some basic human needs that are not being met at home and they come to school to have these needs met.

However, the main push from the teacher of the class I was on yesterday, was to teach content that was not adjusted to meet the needs of the students as individuals. It was straight from the stage based syllabus and so difficult that the students were not just disengaged but were actively protesting and having meltdowns before my eyes. When I suggested deviating from the plan, everyone agreed and calm was restored.

Too often in today’s educational realm, the needs of students are filled with a top-down mentality. Schools start at what the administration identify as a need-based on Australian or state benchmarks and societal goals (eg. NAPLAN, national curriculum or state syllabus documents). They then look to the local administrators to identify needs, such as recent literacy or numeracy training or strategies (eg. L3 or TEN). Then the teachers weigh in (eg. Sport or Creative art or Social-Emotional-Learning – which may or may not be sourced from evidence based practises). Parents and families sometimes get to have a say – and it is interesting to note the capability of the families to engage with the form of communication method chosen by the school as often low SES families cannot get to meetings and cannot access digital forms of communication or are too illiterate themselves to fill in a form – (eg. ‘I want my child to learn how to do public speaking so they can become a prefect or school captain’). Then, almost as an addendum, a little box is put out in the library to gather the student’s identified needs or wants (a system designed to preference students with high enough literacy skills and levels of engagement already to participate).

I prefer to value the student’s needs first – identified by them, identified through a authentic TL relationship with the students, and identified by a thorough a collaborative study of the socio-cultural context (Farmer, et al 2018) of the school. The library and classrooms in the example of the school where I worked yesterday, need to focus on being places for students to have voice and to feel loved and express love. The school needs to be a safe shelter and offer warmth and basic physical comfort. It needs to have a teacher librarian who is acutely aware of the ‘kinder culture’ (Steinberg, 2018) of students in the school and resources the library to embrace the ‘kinder culture’-which is the main key to engagement, particularly with students from low SES, high disability or who’ve been traumatised.

Once these areas have become the main priority for resourcing the curriculum and are working well, and the students are engaged, then the questions can be asked of parents and carers and the community of what they identify as ‘needs.’ Teachers can also weigh in, followed by the local teaching community and administrations. Finally, a little box can be put out for the state and federal needs so that they can have their say.

References:

Farmer, S., Dockett, S., & Arthur, L. (2014). Programming and planning in early childhood settings. Chapter 6. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com

Guilherme, A. AI and education: the importance of teacher and student relations. AI & Soc. (2019) 34: 47. Retrieved from: https://doi-org.ezproxy.csu.edu.au/10.1007/s00146-017-0693-8

McCloud, S. (2018). Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Retrieved from: https://www.simplypsychology.org/maslow.html

Steinberg, R.S. (2018). Kinderculture : The corporate construction of childhood. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com