Tag: Information Society

Censorship creates hackers, curation creates thinkers?

(Reflection on ETL503 Module 2.6)

When I first started this course, my thoughts on information was that it was important to me that everyone have access to all information (Moody 2005), individual limitations such as disability, geography, financial capability/internet access not-withstanding, (as this is a more complex social justice set of issues). I believed information was not something that any person or corporation should own.

When I first started this course, my thoughts on information was that it was important to me that everyone have access to all information (Moody 2005), individual limitations such as disability, geography, financial capability/internet access not-withstanding, (as this is a more complex social justice set of issues). I believed information was not something that any person or corporation should own.

In that sense, I suppose I have the heart of a hacker. Not the sort of hacker who wants to steal a person’s private information in order to rob them, I’m not talking about being a person who commits cyber crime. I am more thinking along the lines of civil liberties and protesting the rise of stringent ‘intellectual property law.’ (Coleman 2012).

Thoughts: in fact, can anyone really own information? … Similarly to the indigenous community beliefs: Does anyone really ‘own’ land: Aren’t people simply custodians of information in varying degrees?

However, as I am studying the Teacher Librarian as information specialist role, I am fine-tuning my beliefs and perceptions. I can now see how curating and resource selection can benefit students (and society) by narrowing down the playing field to a more manageable and relevant space. I am understanding my own motivations better!

Censorship, a historically relevant concept, is motivated by either overt, covert (Moody 2005, pp.145) control, social engineering and seeking proof of weaknesses in information of a whole text – negating any strengths that the information might contain (Ashiem 1953, pp. 63).

Curation (aka resource or information ‘selection’) is motivated by democratically believing in an information seeker’s ability to think, providing others with the freedom to think and read, the freedom to value information within the context in which it was written despite any perceived ‘flaws’ within the minutia of the information (Ashiem 1953, pp. 63, & Lukenbill 2007 pp.28).

When pursuing the path of ‘selection’ of resources or ‘curation’ of resources, TL’s or school resource selectors must then demonstrate ongoing and diligent and consciousness of their (possibly overt or covert) bias and motivations as well as the (possibly overt or covert) bias and motivations of other stakeholders (including ‘community standards’ arguments which seek to take content out of context or limit the range of information available to information seekers, for the purpose of censorship) for selecting or de-selecting resources in order to ensure that they do not cross the line from curation into censorship (Jenkinson 2002 pp. 23, & Moody 2005, pp. 142).

Moreover, rather than be motivated to select or deselect resources based on ‘community standards’, TLs need to focus on providing a range of information and views (Moody 2005, pp. 143) as per Australian ‘industry standards’ such as those provided by ACARA, NESA or AITSL and appropriately curating the library collection to suit the curriculum and the point of need in our individual contexts (Moody 2005, pp. 146, & Lukenbill 2007 pp 26).

Furthermore, if the school library has a formal Collection Development Plan and / or procedure for resource selection/curation/censorship policy section or survey questionnaire for challenges or complaints, then it will offer some protection from external or internal bias and censorship (Jacobson 2016, & ALA 2016).

References

ALA (2016), “Challenge Support” Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/tools/challengesupport

Asheim, L. (1953). Not censorship but selection. Wilson Library Bulletin, 28, 63-67. Retrieved from: http://www.ala.org/advocacy/intfreedom/censorshipfirstamendmentissues/notcensorship

Coleman, E. G. (2012). Coding freedom: The ethics and aesthetics of hacking. Princeton University Press.

Jacobson, L. (2016). Unnatural selection. School Library Journal, 62(10), 20. Retrieved from https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.csu.edu.au/docview/1825615756?accountid=10344

Jenkinson, D. (2002). Selection and censorship: It’s simple arithmetic. School libraries in Canada, 2(4), 22. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.csu.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=lih&AN=7277053&site=ehost-live

Lukenbill, W.B. (2007). Censorship: What do school library specialists really know? School Library Media Research, 10. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/aasl/sites/ala.org.aasl/files/content/aaslpubsandjournals/slr/vol10/SLMR_Censorship_V10.pdf

(2005) Covert censorship in libraries: a discussion paper, The Australian Library Journal, 54:2, 138-147, DOI: 10.1080/00049670.2005.10721741

Musings of an Apprentice Information Specialist

Following my ‘pass’ on my Discussion Essay (Assessment 2) for Introduction to Teacher Librarianship (ETL401) I had another look through the forum posts for Module 2 from my colleagues this week and I wrote notes of my thoughts as I went along:

INFORMATION: A school context must come to an agreed understanding to a definition of, opinions of, and methods for seeking and absorbing information. Thus, we will have a better understanding of what is an ‘information specialist’ or ‘information literacy’ or ‘information (insert word here)’.

MULTI-LITERACIES: Back in my UWS studies in 2003-2006, we didn’t learn much about how to implement Guided Reading groups using PM Readers (ugh, I despise this method of teaching anyway) but we did a fair amount of study around ‘multi-literacies’ (Lilly & Green 2004 p.99 & 118, Worthington & Carruthers 2003 p.12, Arthur 2001, & Barratt-Pugh & Rohl 2000 p. 198-201).

[Sidebar: In fact, in my NSW Department of Education (DET) job interview in 2006, I was asked how I would implement my English program and when I answered academically, with my knowledge of ‘multi-literacies,’ I failed the interview and was told to do another practicum in a primary school (although that was not officially a requirement of the DET) in order to ‘pass’ my interview and be granted a teacher number. The head of the panel, a high-school principal, was worried that I wouldn’t implement the traditional Australian primary school English content and would create a generation of illiterate students, I suppose. Thankfully, I did as she asked and got the job easily the second time around…interesting how ‘multi-literacies’ has come full circle in the form of ‘information literacy’ as well…but I digress.]

GOING GLOBAL: Information has become more global, as has our society, with the introduction of digital technologies and the ‘world wide web.’ This means that we, as Teachers and Teacher librarians must be more flexible with our students as global citizens, acknowledging and integrating: multiple languages, multiple cultural norms, multiple methods of information seeking, multiple methods of information absorption (aka ‘learning’), multiple learning styles (that change depending on an individual person’s context in any given moment in their lives) and multiple ability levels.

Is information that is globally available, much like the fancy car that a rich family buy their inexperienced teenager, less valued? If it comes too easily will it get taken for granted and generally end in a car crash?

Is information that is globally available, much like the fancy car that a rich family buy their inexperienced teenager, less valued? If it comes too easily will it get taken for granted and generally end in a car crash?

SOCIAL MEDIA: The global network has also seen the creation of ‘social media’ and ‘wiki’ spaces. This impacts on people’s learning because, while social media is an excellent tool for engagement and delivery of information (linked to the research and marketing analytics done by corporations on how to reach target audiences–particularly children as per Veltri, et al 2016), social media is a weak platform in which to apply knowledge to every day reality. It is a sub-reality. A false replication of actual society with real, living and breathing humans and human interactions.

This is evident in any situation where someone makes an educated statement on a social media platform and is then hit with a barrage of abusive comments. People on social media platforms go on to social media platforms in order to be ‘social’–they aren’t there to be educated and aren’t open to absorb information, particularly if they have to work for it or if said information puts them out of their comfort zones and into a learning pit.

NAVEL GAZING: I wonder if the prevalence or demand for self expression on social media has been  born from the American talk show and self-help movement? Much like these movements who focus ‘in rather than out,’ (Murray 2015) could social media confuse the lines of what is a therapy tool, versus valuable information or accurately tested and researched knowledge?

born from the American talk show and self-help movement? Much like these movements who focus ‘in rather than out,’ (Murray 2015) could social media confuse the lines of what is a therapy tool, versus valuable information or accurately tested and researched knowledge?

ACADEMIC SOCIAL MEDIA: When we blend academia with social media, do we then, in turn, blur lines of authenticity for students? Why are some blogs academic and some mere musings? Is the blurring of academic information being part of the deep web versus readily available on the internet a clever way of engaging students in academia, embracing the method of delivery preferred by 21st century learners?

EASY TO FIND OVERLOAD VS RESTRICTED ACCESS DEEP WEB: Both are problematic. Historically, libraries have suffered the weight of hoarding and politicalisation of information. Encyclopaedia Britannica have a great topic page on their website (El-Abbadi 2019) about the Library of Alexandria which details how the Royal library and its ‘daughter’ library the Serapeum were destroyed by fire and war.

Great swaths of information have been destroyed in the past, and in today’s global information network, we are drowning in misinformation, irrelevant information, and less connection to information.

We are slightly more organised on the deep web, which is less susceptible to misinformation, but more likely to segregate and discriminate against users, particularly to society’s lower classes.

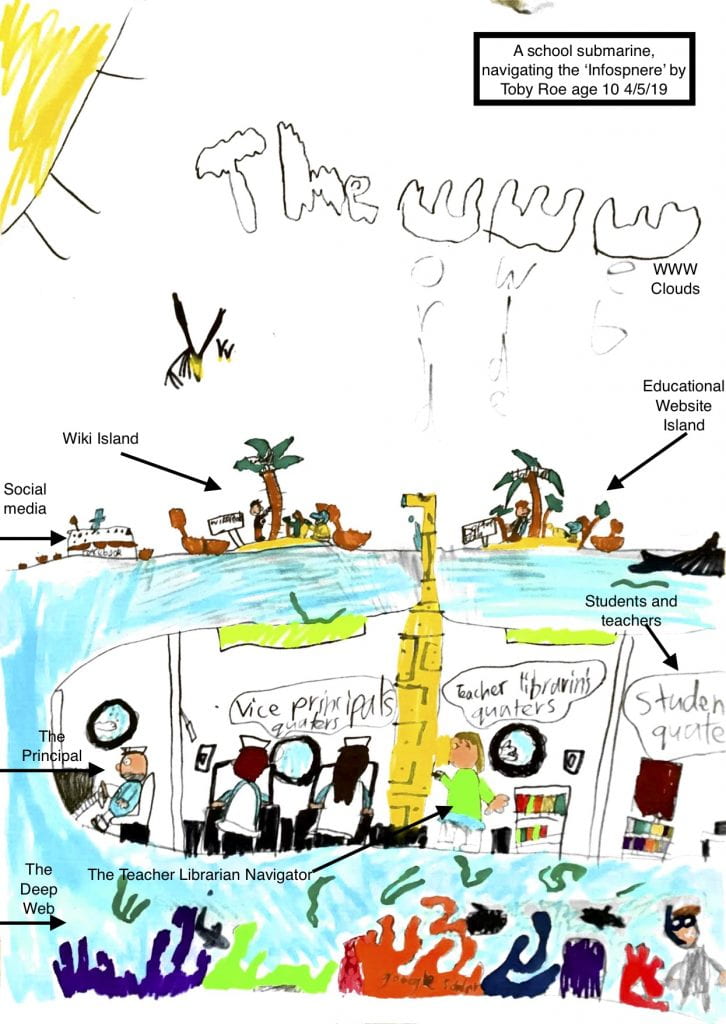

THE TL ROLE: In order to be valued as TL who are information specialists, we are the navigators and we need tools like telescopes, compasses and maps to help the ship navigate the ‘infosphere’ (Floridi 2007). We must safely navigate towards islands of internet information and cruise ships of social media. We must safely navigate below the water, helping the ship find and understand the underwater volcanoes and creatures of information.

TL’s need to:

- remember how to use digital technologies

- but to still keep in mind that using social media for work purposes is like working while on holiday, particularly for some teachers and teacher librarians who are suffering from stress or burnout, or who are trying to stabilise their work/life balance and

- we must strive to enable students to go through the stages of the Learning Cycle,

- use evidence-based practice,

- be aware of theories and pedagogies that we have been using as teachers, such as Multiple Intelligences and/or the Berry Street Educational Model (BSEM) for trauma informed practice or Quality Teaching Rounds, and

- work collaboratively with all stakeholders, much like the crew of a submarine!

Teacher Librarians need to be the navigators of the (school) submarine. The principal and executives are the captain and first mates. The teachers are the crew and the kids, the families are the passengers. The submarine needs everyone to work together in order to be able to navigate the information sea above the water, including the political breezes and cultural water currents, the social media cruise ships and the various modes of information islands. It also needs to be able to safely navigate below the sea in the deep web with all of the volcanic deep web databases, applications and sea creatures that lurk about in the darkness.

References:

Arthur, L. Young children as critical consumers. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy. Oct 2001. v24. i3. p.182(14).

Barratt-Pugh, C. & Rohl, M. (2000). Literacy learning in the early years. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

El-Abbadi, M. (2019). Encyclopaedia Brittanica. Retrieved from www.brittanica.com/topic/library-of-alexandria

Floridi, L. (2007). A look into the future impact of ICT on our lives. The Information Society, 23, 59-64. CSU Library.

Lilly, E. & Green, C. (2004). Linking Home and School Literacies. Developing partnerships with families through children’s literature. NJ: Pealson.

(2015) Notes to self: the visual culture of selfies in the age of social media. Consumption Markets & Culture, 18:6, 490-516, DOI: 10.1080/10253866.2015.1052967

Worthington, M. & Carruthers, E. (2003). Children’s Mathematics: Making Marks, Making Meaning. London: Paul Chapman Publishing.

Veltri, G. & Lupiáñez-Villanueva, F. & Gaskell, G. & Theben, A. & Folkvord, F. & Bonatti, L. & Bogliacino, F. & Fernández, L. & Codagnone, C. (2016). (Radboud University) Study on the impact of marketing through social media, online games and mobile applications on children’s behaviour. Published by Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.1.2576.7280.

Being Part of an Information Society

(Reflections of Introduction to Teacher Librarianship Module 2.3)

Knowledge is power. While I most definitely believe that I will become a librarian at some point I will always be a teacher and this amalgamation of ‘teacher librarian’ means that I am a facilitator of education. This is a key component of my teaching philosophy.

I am most disturbed by the concept of inequality and injustice and as such, I am uncomfortable with the idea that information is, as discussed by WebFinance, 2016, in Module 2.3:

“the (1) pervasive influence of IT on home, work, and recreational aspects of the individuals daily routine, (2) stratification into new classes those who are information-rich and those who are information-poor, (3) loosening of the nation state’s hold on the lives of individuals and the rise of highly sophisticated criminals who can steal identities and vast sums of money through information related (cyber) crime (WebFinance, 2016).”

The growth of technology in our lives has created, in some ways, more questions than answers:

- Why is technology so pervasive? (How do I get my husband to put the phone down and look at me when I am speaking to him???)

- What can we do to stop it from creating a new class system or intensifying the status quo? (Particularly given the first question which makes me want to go live in the Amazon and leave technology behind. And if I didn’t have technology who is to say that I would be disadvantaged? Would my life have greater quality rather than quantity?)

- Does it really ‘loosen the nation’s hold’ on our lives? (Is it a bad thing that ‘the nation’ hasn’t got a ‘hold’ on ‘us?’ Who is it exactly that has a hold on ‘us’? Governments? Special Interest Groups? Corporations? Computers?)

- Why does it increase the occurrence of identity and other theft? (Why are people so horrible to each other on the digital sphere?)

Proposed questions (and my answers) from Module 2.3:

“Who or what is driving technological change–Is it the inhabitants of the landscape or the technology?”

I believe the drive for change and continued growth of technological advances has to do with the people and the pursuit of democracy (Coccia 2010) as well as the economy (mainly capitalism as noted by Schiller in Webster 2014, p. 149) and competition between countries-most notably in the ‘space race’ and the Cold War (Godwin, 2006).

I also think the need of all humans is to improve the world in which we live, even if it is a small way, is an important factor towards careers that drive change, be they careers that drive technological change or societal injustice change or both.

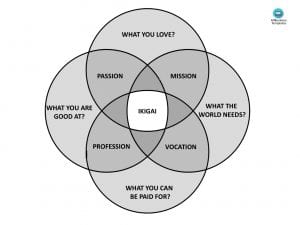

This need to be of value to the world is a key factor of a Japanese concept called Ikigai (Garcia & Miralles, 2017) which is a principle of life that can exist without being consciously aware that it exists.

Does technology itself drives the agenda (and rate of change) or is society in control?

I hope we are still in control but I honestly could not say for certain and perhaps that, in itself, should be cause for alarm.

Should teacher librarians be considered part of the ‘Information Society’?

As I said at the start of this post, I am (or will be soon) a teacher librarian. My skills as a teacher–as a Quality Teaching Framework trained, NESA Proficient (and maintained) Teacher is not negated by the need to ensure that information is made available to the students and school in which I teach.

My teaching philosophy may grow and change and I may be part of an information society–but one thing will always remain: Teachers are facilitators of education (more than an transmitters) of information.

References:

Coccia, Mario. (2010). Democratization is the driving force for technological and economic change. Technological Forecasting and Social Change. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/248497849_Democratization_is_the_driving_force_for_technological_and_economic_change

Garcia, H. & Miralles, F. (2017) Ikigai: The Japanese Secret to a Long and Happy Life. London: UK. Hutchinson.

Godwin, M. (2006) The Cold War and the Early Space Race. Retrieved from: https://www.history.ac.uk/ihr/Focus/cold/articles/godwin.html

Web Finance Inc. (2016). Information Society. Retrieved from Introduction to Teacher Librarianship Module 2.3: https://interact2.csu.edu.au/webapps/blackboard/content/listContent.jsp?course_id=_42380_1&content_id=_2633951_1&mode=view

Information and the digital age – Positives and Negatives

(Reflection of Module 2.2 Introduction to Teacher Librarianship)

Western society has easy access to information. It might not always be up to date or relevant to our individual contexts but it is available.

5 positives of the digital age:

- It is faster than doing research using a library or non-fiction text that has been purchased.

- Levels the playing field to some degree for economically disadvantaged communities.

- Levels the playing field to some degree for geographically disadvantaged communities.

- More people have a venue for having a ‘voice.’

- Creates an avenue for collaboration that was not there previously.

4 negatives of the digital age:

- Relies on the assumption that the entire world are having equal input when that is not true.

- Opens the gate to misinformation (eg. propaganda) to reach a larger audience for the sake of another’s personal gain.

- It takes a lot of time to weed out the stuff we don’t want or need to see (this having previously been done by editors and publishers or researchers in their fields). [Search engines try to help with this by programs where ‘the tool directs the user’. These algorithms try to guess what you-the user-want to see. However, this places inhuman limitations on the information that we seek and can often miss the mark. The intelligence is artificial and cannot offer clarification the way that a human can].

- People (eg. teachers) will most often see only the good things that others (in their profession) put on the internet and not the reality.

References:

Case, D. (2006). The concept of information. In Looking for information: A survey of research on information seeking, needs and behaviour, pp. 40-65 (Chapter 3). 2nd ed. Burlingham: Emerald Group Publishing Ltd. ebook, CSU Library.

Floridi, L. (2007). A look into the future impact of ICT on our lives. The Information Society, 23, 59-64. CSU Library.