[Reflection on ETL503 Module 2]

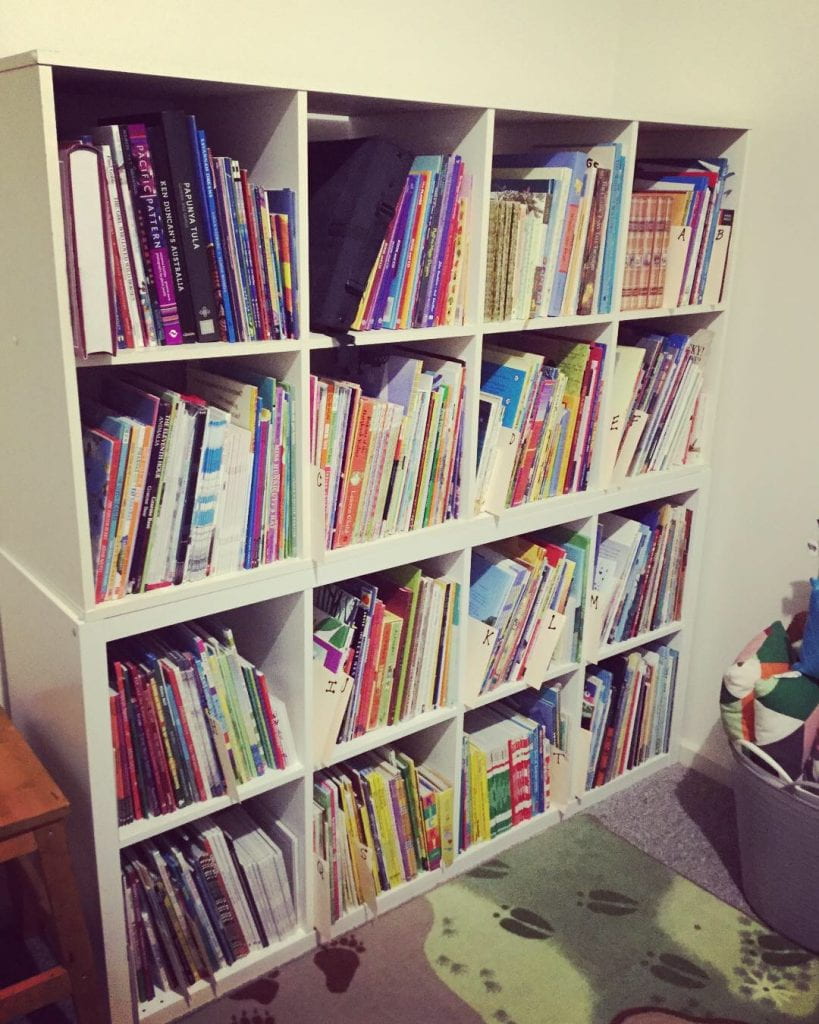

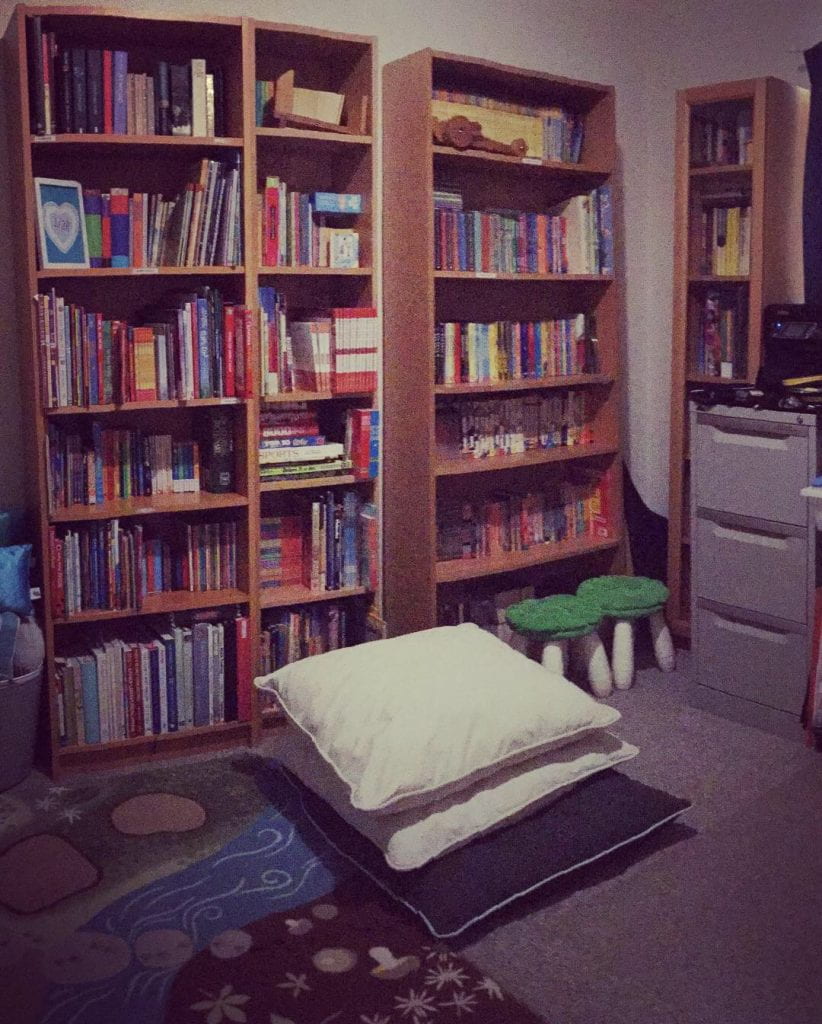

Recently I weeded (deselected) my personal library. (Most of the books in the attached images had lived their lives previously in either mine or my husband’s classrooms, which had to be packed up at the start of this year and put into storage as neither of us are ‘on class.’)

I had a box of romance novels from my late teens early 20’s and a collection of crime fiction from my early 20’s and 30’s that I thought I would want to keep forever but in fact, following moving house twice, they simply took up storage space. [IN FACT, fair disclosure: don’t be misled by how organised it looks now–the room pictured was previously a toy room and the books were in a different room packed floor to ceiling with boxes!]

In accordance with Marie Kondo’s (2019) KonMari method (originally a book, now a series on Netflix), many books did not ‘bring me joy.’ It was liberating to get rid of them–except for my collection of Sue Grafton mass market books, as her A-Z series hasn’t finished yet, let’s not get crazy! [Sidebar: Marie doesn’t say you have to get rid of any particular number of books. Relax.]

I decided to weed out some of our student fiction books. I kept some ‘classics’ and all books with matching CDs or automated reader capabilities (hugely popular). I kept all books by known authors and those that were part of a series (breaking a series or getting rid of a series hurts my heart – was I feeling guilted into keeping them? Possibly). But a lot of the books that I got in Scholastic book fair mixed author ‘packs’ or at Scholastic ‘box of books for $40’ warehouse sales got the axe with no regrets.

Asking myself, ‘does this book bring me joy?’ the main cull of books also came from my non-fiction shelves. My husband (also an educator) and I managed take about 10 boxes of books to Lifeline. Our reasoning: the information inside them was available online and a lot of the information in the books that we owned had gone out of date.

However, when we took the books to Lifeline, a parent from one of our local schools wanted all of them. In our area, most families are living below the poverty line and don’t have access to a lot of books and many don’t have a home computer. And, to be fair, these books have been read so often in our classrooms that they were falling to bits. The parent took them to the local ‘toy library’ facility where they will hopefully be loved and utilised as a means to teach young children initial literacy skills and surround them with literature.

So I’ve been reading the modules for ETL503 again and I’m asking myself now, which do students in our area need/want/prefer: Fiction or Non-fiction? What is the difference between a need vs want and does it really matter when resourcing the curriculum? Why do teachers (and TLs) keep resources, is it because of guilt or joy?

Fiction vs Non-fiction: Which one students prefer depends on the students themselves and what they are doing in any given point in time. To pit one type of text structure against the other is comparing apples and oranges. In my classrooms, students select non-fiction if they are only allowed a short amount of time for reading. If they are given more time, they select a trending fiction text. If they are new readers, they select storybooks we’ve studied in class (and invariably want to read them out loud to someone – preferably an adult!) If they are sharing a book with a friend, they go for the Joke books, Search and Finds, or books like the Guinness Book of World Records.

Sometimes, as students get older, they might think fiction books are for babies (or maybe they find them too romantic or disconnected from their lives –anyone tried to study Romeo & Juliet in high school? Was that fun for the majority of the boys in the class…?) and they might prefer non-fiction for a time. My husband and his younger sister profess to have never enjoyed reading fiction texts for pleasure, however, they have always enjoyed reading biographies or “non-fiction personal narratives” (Mosle, 2012).

In fact, the question of fiction vs non-fiction is the wrong question.

A better question would be: What is the library’s (and in fact, the school’s) main goals? What are students trying to achieve and what kind of resource would help them meet their personal and educational goals?

Are students reading for pleasure without an intentional or identifiable goal other than pleasure, and what do they identify as pleasurable–fact or fiction? Are students reading for obtaining information or skills that will enable them to achieve a particular goal or pursue a particular interest in their educational journey, and what will help them meet these goals–fact or fiction?

Need vs Want: Adults can be so presumptuous when deciding what children need vs want! Why does it have to be one or the other? Have you ever been in a school where they prohibit children from playing ‘shooting’ games using sticks or lego built ‘guns’? This is part of their ‘kinder culture’ and social development and isn’t indicative of future violence as adults (Alexander 2015). Have you ever worked in a setting where Barbie dolls weren’t allowed because of the presumed negative body image ideas that these dolls might encourage?

The lines between reality and imagination are very blurred for young children. There is, theoretically, no harm in this behaviour because adults have been using it to their advantage for centuries: by reading texts about fictional characters, children learn societal norms and preferred moral behaviours (Sekeres 2009). Children connect with fictional characters in a similar fashion to how they connect with real people and have a sub-culture that is entirely their own.

“Notions of childhood are more complex, more pathologized (sic) and more alien to adults who educate and parent” (Steinberg 2018, pp.2).

In this world of trying to ascertain what students at a given context NEED, it is important to recognise our own bias and preconceived notions before we acquire resources.

When looking at stages of development and trying to identify student NEED, we must not be fooled into thinking that these are a fixed, unchangeable means with which to view our students. When matched with an incongruent benchmark, students of today will be falsely judged as not ‘making the grade’ and could in turn have low expectations of themselves (Steinberg 2018). Students who believe they’ve ‘measured up’ to adult expectations may believe it due to their ability when in fact their success is more closely related to race and privilege (Steinberg 2018, pp.4).

Students can tell us what they WANT and that will simply have to take precedence over what we as educators think they NEED.

Once students have been asked and their voice has been heard, we can pursue our own agendas, as identified by Kimmel (2014):

“The school library collection serves the mission, goals, and objectives of the school, the school system, and the state. Our first consideration should be our learners— both present and future. The clientele of the school library and the curricula should inform identification of the ideal collection. Curricula, including local, state, and national standards, are important considerations. Identifying gaps also requires knowledge of the current collection. A needs assessment, therefore, develops a vision of the ideal collection needed to meet the needs of students and the mission of the school, and then measures this ideal against data about the current collection.” (Kimmel 2014, pp. 25).

Guilt vs Joy: Let’s not keep resources simply because we feel guilty getting rid of them. Let’s not be hoarders…has anyone else gone into a school library and thought: Does anyone actually read any of these old books? Why is this still here? What is that pile? What is in this filing cabinet? Why are there 10 old radios on this shelf? Do we even have computers that could read all of these floppy discs any more? I have been into a library like this, and it was traumatising.

We can’t keep things just because we think someone MIGHT need it in the future. We need to recognise what WILL be used in the future and what HAS been used in the recent past.

When weeding a collection, including equipment, Kimmel (pp. 67-68, 2014) recommends we ask ourselves and survey as required: In our school context and given our goals and curriculum needs, is (any particular resource): in good condition and / or appealing? Is it current? Is it relevant to stakeholders?

When I am a TL and/or next time I move house, I will continue to consider my collection as it relates to my learning in this course…possibly hanging on to those non-fiction texts a bit tighter. Until then, on to the next module!

References

Alexander, S. (2015). Superheros and Weapon Plan for Fun and Learning. MyECE Experts. Retrieved from: https://www.myece.org.nz/activities-for-childhood-learning/254-superhero-play-weapon-gun

Kimmel, S. C.. (2014). Developing Collections to Empower Learners, American Library Association. Retrieved from: ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/csuau/detail.action?docID=1687658.

Kondo, M. (2019) KonMari. Retrieved from: https://konmari.com/

National Library of NZ. (2014). Non-fiction. National Library of New Zealand Services to Schools. Retrieved from: https://web.archive.org/web/20160729150727/http://schools.natlib.govt.nz/creating-readers/genres-and-read-alouds/non-fiction

Mosle, S. (2012, November 22). What should children read? [Blog post]. Opinionator: The New York Times. Retrieved from: https://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/11/22/what-should-children-read/?_r=0

Sekeres, D. C. (2009). The market child and branded fiction: A synergism of children’s literature, consumer culture, and new literacies. Reading Research Quarterly, 44(4), 399-414. Retrieved from: http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.csu.edu.au/stable/25655466?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

Steinberg, S. R. (2018). Kinderculture : The corporate construction of childhood. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com