Tag: Evaluation

Social Media in ‘Your’ Organisation – Reflection on INF506 Module 4 and Assessment 1

OLJTask 10: Defining librarian 2.0

I don’t have an ‘organisation’…but I have the goods!

While I did read the module, I simply did not have time to read everything thoroughly and then complete this post before I submitted my first assessment. Thus, this reflection is written in support of that assessment and how I could have improved it having now read the module in detail. (As I write, I have received my assessment back and I have passed so that is a relief!)

I am not currently working in a library so that aspect of my reflection below will be based on my past experiences. It is also the reason a lot of my approaches seem too broad – I haven’t yet accomplished the level of practical experience required to narrow the roles and responsibilities of TLs down to the nitty gritty. That said, however, I recently attempted a job interview as a librarian in a local public library and they asked what I bring to the role. I floundered a little, but I said something like, I am focused on the library users, I have a positive attitude and I am flexible – very similar to the ‘customer service focus, strategic viewpoint and ability to be adaptable and resilient’ presented by Burton (2019, p.44).

So too do I have an open approach to programs that I will attempt and a modern take on what it means to be a teacher librarian in the 21st century. Chun (2018) lists some great attributes of TLs, which I believe I possess: user-driven focus – particularly for students, passionate, collaborative, innovative, risk-takers, leaders, evaluative – readily seeking and accepting feedback for growth, ever increasing their knowledge scope, and a consistent willingness to try new things. King (2018) adds ‘trend watcher’ to this list (in terms of the digital age) which I believe is most easily monitored via social media and applications like Diigo (mentioned in my assessment).

Did you thoroughly discuss web 2.0 or library 2.0?

I think the design process recommended by Bell (2018) is simple but beautiful: what’s the need, why is it a need, how can we fulfil the need? Change is necessary and the simpler the approach, the better.

In particular, the in assessment 1, I did not cover enough (or anything?) about the importance of having a change to web 2.0 minimum approach to social media in an organisation. Miller (2005) was writing about it 15 years ago, ergo, it isn’t new, by any stretch in technology terms, much less the term ‘library 2.0’, reimagining the library in a user-centred model for 21st century library services (Casey & Savistinuk, 2006). Here are three quotes that struck me particularly:

“The heart of Library 2.0 is user-centered change. It is a model for library service that encourages constant and purposeful change, inviting user participation in the creation of both the physical and the virtual services they want, supported by consistently evaluating services. It also attempts to reach new users and better serve current ones through improved customer-driven offerings” (Casey & Savistinuk, 2010, p.40).

“If we are not responding to the experiences our members are receiving in other cultural, learning, and retail industries, then we risk being irrelevant for our communities’ immediate and future needs” (Jane Cowell in Hoenke, 2018, p.7).

“What makes a service Library 2.0? Any service, physical or virtual that successfully reaches users, is evaluated frequently, and makes use of customer input is a Library 2.0 service” (Casey & Savistinuk, 2010, p. 42).

(Note: This user-centred or user-focussed approach has been mentioned in my blog previously and also in my second assessment on the positives and negatives for library resource genrefication, written for ETL505 Describing and Analysing Educational Resources).

(Note: This user-centred or user-focussed approach has been mentioned in my blog previously and also in my second assessment on the positives and negatives for library resource genrefication, written for ETL505 Describing and Analysing Educational Resources).

Yet, despite social media’s ‘coming of age,’ I have encountered quite a bit of resistance to interactive social media in the workplace. One principal (no longer in the same role) explicitly forbade it on school grounds. Indeed, teachers were not allowed to even have their phones out at school at any time and she was very clear that we would be terminated if we were caught. The lady who ran the canteen (a seasoned local, much respected) had a Facebook (FB) page for the school canteen and kitchen garden at the school. One year, I added photos to her FB page that I’d taken while teaching in the school kitchen garden (in my role as the kitchen garden teacher, being careful to only upload those images without people in them) and one of the principal’s friends (the librarian no less, also no longer at the school) ‘reported’ it.

I remember had to sit in the principal’s office and show her what I had uploaded and who was running the FB page, proving it wasn’t myself and that I had not dared to cross her (as if I would!). It was a ridiculous situation that was only helped that the images were (and still are) lovely representations and promoted what was one of the most important programs at the school. To this day, the school and surrounding schools in the town have a very reserved approach to social media which I find ‘safe’ but at the same time quite sad.

After reading Casey & Savistinuk (2010) libraries or schools who prohibit social media (or worse, get rid of the library all together, such as a local high school recently did in my area, refusing to reimagine the space as a Library 2.0) have lost the opportunity to ‘harness collective intelligence’ of the community and limited their ability to ‘tap into users via the long tail’ – i.e. they simply provide the same services to the same groups, fearing and avoiding change, without considering that they could allow users to anonymously comment or offer feedback on the collection or services and grow.

Did you mention privilege?

School administrators who refuse to partake in social media, omit a ‘tech savvy’ portion of society (Williams, 2018) who use social media as their primary method of communicating with the library or school – generally speaking, those who simply find it easier to use (not to mention those who are from lower socio-economic status (SES) who are traumatised or marginalised, or who have limited access to academia or literacy levels). This is supported by Admon, Kaul, Cribbs, Guzman, Jimenez, & Richards (2020, p.500) who point out that social media creates “an open forum by disrupting the boundaries of geography, position, institution, and hierarchy.” (And, although I’m not sure that I’m ready to run a ‘Twitter chat’ session for an organisation myself, as recommended by Admon et al. (2020), I appreciate their recommendations and will refer to them should a Twitter chat be warranted in future).

Certainly, having lived in Broken Hill for 6 years, I can attest that Facebook (linked to Instagram) was the primary source of advertising used by local businesses and community services – simply for the fact that everyone was on it and it was basically free (omitting the cost of the technology and internet).

Perhaps it is well and truly time for librarians and school administrators to consider our perceptions of privilege in our user-centred approaches to the library and in our communications with society. ie. Are we avoiding social media because we want to push our academic forms of communication onto a society who will only suffer from our position of power over information?

Perhaps it is well and truly time for librarians and school administrators to consider our perceptions of privilege in our user-centred approaches to the library and in our communications with society. ie. Are we avoiding social media because we want to push our academic forms of communication onto a society who will only suffer from our position of power over information?

Did you consider access in terms of ability?

Enis (2018) points out that we cannot just have the latest most whiz-bang applications and software but we also require facilitators (e.g. teacher librarians) to help our patrons utilise and access them as required. Furthermore, something else I note about my assessment was that my proof reader had recently completed an access related course where she said that I needed to change how I mentioned the image in my assessment so that I described it for those who might be colourblind. This links to the TEDtalk mentioned in Module 4: ‘If we consider our library a user-focused library, we need to tailor access for everyone, including those who rely on social media for connections to the library or school.’

Did you point out not just ‘doing’ social media but doing it well?

While I particularly covered aligning the social media recommendations with the broader school plan. I like the ideas from Rathore (2017), as well as those from Rossmann (2019) to align the social media project with the ‘broader communication plan‘ and am curious how many school libraries and schools in general actually have a communication plan…?

I did mention doing social media ‘well’ in my assessment, but I don’t feel I supported my comments aptly, having not mentioned Rossmann’s (2019) article which goes into ‘social media optimisation’ in depth. In addition, the argument for not just ‘doing’ Library 2.0, but doing it well is made very clear in the below TED talk:

Did you mention networking between librarians?

Another item that I did not mention in my assessment are the networking links between schools (lead by the teacher librarians). Just as the networking that prohibited social media in my previous setting, so too could networking help support tentative schools in taking the plunge into library 2.0 concepts and web 2.0 social media connections (and even web 3.0 interactive applications), as recommended in Cole (2016, p.9) challenging the library’s role as a “fixed community asset…(making its scope) unfettered by static definitions.” (What was obviously lacking in that scenario was simply leadership).

Did you discuss project management and the various means of evaluation?

I did touch on project management / change leadership in terms of the timeline and involvement of a digital learning environment leadership team in my project proposal assessment. However, I would have liked to have more formally included the ideas recommended by Allen (2017) also, including: identifying and researching user needs, identifying and researching the project’s aim(s) based on the context’s vision/mission/strategic plan and the potential impact of the project on those needs, having clear measures for success – while still accepting a margin of trial and error, consideration for the context and norms within it, discussing the types of stakeholders/project groups and the required levels of communication/input, assessing the risks, and providing a basis for future professional development and growth of the context. Furthermore, of particular interest, is the project management table by Allen (2017, p.54) that I could have used (among other great tables by Allen). I also liked the ideas from Bell (2018) which recommends the Design Thinking Toolkit for Libraries (with free downloadable toolkit) and the ‘Its Broken’ video by Seth Godin.

When it comes to the evaluation stage of the project, again, I don’t think I fully discussed the scope required for evaluation of the recommendations in my assessment. All services, new and old, require a schedule and means for evaluation across the whole context and beyond – current staff, users, community members and those we are trying to gain via outreach (Casey & Savastinuk, 2010).

References

Admon, A. J., Kaul, V., Cribbs, S. K., Guzman, E., Jimenez, O., & Richards, J. B. (2020). Twelve tips for developing and implementing a medical education Twitter chat. Medical Teacher, 42(5), 500-506. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2019.159855

Allen, B. (2017). Getting started. In The No-nonsense Guide to Project Management (pp. 49-70). Facet. doi:10.29085/9781783302055.003

Bell, S. (2018). Design thinking + user experience = better-designed libraries. Information Outlook (Online), 22(4), 4-6.

Burton, S. (2019). Future skills for the LIS profession. Online Searcher, 43(2), 42-45.

Casey, M. & Savastinuk, L. (2010, May 21). Library 2.0: Service for the next-generation library. Library Journal.

Chun, T. (2018). “Brave before perfect”- A new approach for future-ready librarians. Teacher Librarian, 45(5), 35-37.

Cole, L. (2016). BiblioTech as the Re-Imagined Public Library: Where Will it Find You? Paper presented at: IFLA WLIC 2016 – Columbus, OH – Connections. Collaboration. Community in Session 213 – Metropolitan Libraries.

Enis, M. (2018). Adding Apps. Library Journal, 143(6), 24–25

Hoenke, J. (2018). A new career in a new town. Information Today Inc. 35(7).

King, D. L. (2018). Trend watching: Who and how to follow. Library Technology Reports, 54(2), 14-23.

Miller, P. (2005, October 30). Web 2.0: Building the new library. Ariadne, 45. http://www.ariadne.ac.uk/issue45/miller

Rathore, S. (2017, August 22). 7 Key steps in creating an effective social media marketing strategy. [Blog post]. https://www.socialmediatoday.com/social-business/7-key-steps-creating-effective-social-media-marketing-strategy

Rossmann, D. (2019). Communicating library values, mission, vision, and strategic plans through social media. Library Leadership & Management, 33(3), 1-9. doi:10.15788/2019.08.16

Williams, M. L. (2018). The adoption of Web 2.0 technologies in academic libraries: A comparative exploration. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000618788725

Best practice for leading and supporting digital citizenship

(Reflecting on my learning in ETL523 Modules 4, 5 & 6)

“Digital leaders understand that we must put real-world tools in the hands of students and allow them to create artefacts of learning that demonstrate conceptual mastery. This is an important pedagogical shift as it focuses on enhancing essential skill sets—communication, collaboration, creativity, media literacy, global connectedness, critical thinking, and problem solving – that society demands….Leaders need to be the catalysts for change…..Digital leadership begins with identifying obstacles to change and specific solutions to overcome them in order to transform schools in the digital age” (Sheninger, 2017).

Notably, in terms of creating a productive digital learning environment, Sheninger (2017) identifies ‘7 pillars for digital leadership in education’ as: communication, public relations, branding, student engagement/learning, professional growth/development, re-envisioning learning spaces and environments, and opportunity.

Rather than avoid global connections and social media, and rather than limit our students (forcing them to go ‘underground’ with a secret world of digital environments of their own making) we need need to learn how to embrace it safely and productively as global digital citizens (Ohler, 2011). We also need our school principals and supervisors to help promote a community of practice and positive learning environments by being “willing to listen, delegate, distribute, empower, and step out of the way of the learning” (Lindsay, 2016, p.110).

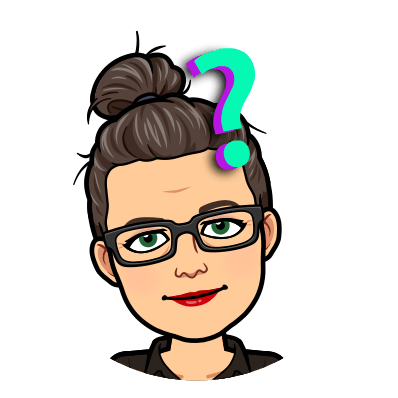

Utilising the readings for modules 4, 5 and 6, as well as a few of my own, following the 6 month multi-phase structure suggested by Chen & Orth (2013), Cofino (2012) and Common Sense Media (n.d.) which begins prior to the start of the school year, we can complete the following 4 phases:

-

Prior to the school year beginning, school contexts need to begin phase 1 by clarifying our unique vision, goals, roles and responsibilities:

- First. form a strong team of information and digital technology leaders (Chen & Orth, 2013; Common Sense Media, n.d.). (See my previous 9 blog posts on creating a school Community of Practice or the evaluation of practice via the 3 blog posts on Quality Teaching Framework/Rounds and also this video on Teacherpreneurs from the Centre for Teaching Quality for motivation!)

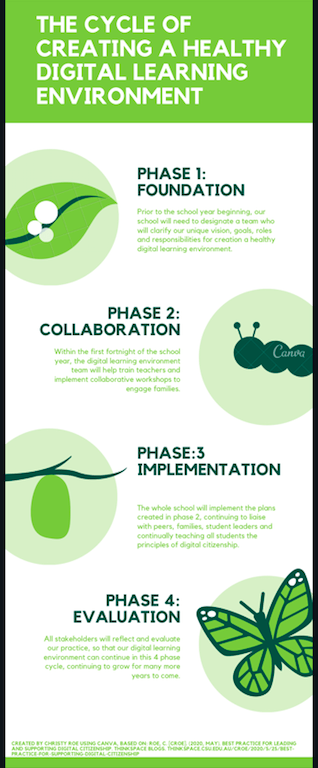

- Create and deliver an environmental scan utilising this template for a ‘Situational Analysis’ by Christy Roe (based on suggestions from) the resources provided by Hague & Payton (2010), and/or Pashiardis (1996), particularly as shown in the hexagon images below:

Digital Literacy Planning Tool ‘Reflect & Progress’ image by Hague & Payton, 2010, p.47 - Implement a technology audit (such as this one created by Christy Roe) and/or bullying survey (such as this one created by the University of South Australia) (Chen & Orth, 2013).

- Facilitate the formulation of policies, procedures or guidelines such as an acceptable use policy (using a questionnaire such as this one created by Christy Roe) based on the policy created by the administration (such as those listed in the resources section below), including cohesive terminology that we will utilise as a school (Common Sense Media, n.d.), e.g. linking the Positive Behaviour for Learning Behaviour Matrix or Code of Student Conduct to the school’s “Acceptable use Policy (AUP), Responsible Use Guidelines (RUG), Acceptable Use Agreement (AUA), Internet Use Policy (IUP), Bring Your Own Device (BYOD), or Bring Your Own Technology (BYOT)” etc.

- Liaise with others in our personal learning networks (PLN) (Sheninger, 2017) to map the digital citizenship areas of the syllabus or curriculum documents (NESA / ACARA), find examples of a digital citizenship scope and sequence (such as this (2011) one by Mike Ribble), develop sample lessons or units of work, and accumulate appropriate resources (such as those provided in the resources section below)–made available to all stakeholders (Common Sense Media, n.d.).

- Allow teacher librarians (and the school leadership teams) to readily undertake the role of information leaders who ‘meet the students where they are,’ recognising that there may not only be gaps in terms of technology access, or information access, but there may also be an (intergenerational) gap between what some view as the purpose of technology – i.e. is the purpose of technology to assist in informing, socialising or varying degrees of both, and what is true for the individuals in each school or home context? (Levinson, 2010, p.11).

2. In phase 2, within the first fortnight of the school year, we must train teachers and engage families:

“Alignment between school and home with regards to digital citizenship and healthy digital usage is a hallmark of a 21st-century school. A community-wide understanding of the norms, rules of behaviour, rules of engagement, and common practices is necessary for all schools in order to raise an ethical, digital (and real-life) citizen. Without this key parental partnership, these conversations regarding digital citizenship will just become incoherent whispers in the minds of our students, overwhelmed by the louder voices of media, false information, and misunderstanding” (Chen & Orth, 2013).

- As per the circles image from Hague & Payton (2010) (as well as information from Sheninger (2017)), schools and families need to continually foster 21st century learning and digital literacy skills such as: creativity, (innovation), critical thinking, evaluation (and problem solving), cultural and social understanding, collaboration, effective communication, (global collectedness), the ability to find and select information, (media literacy), e-safety and technological functional skills.

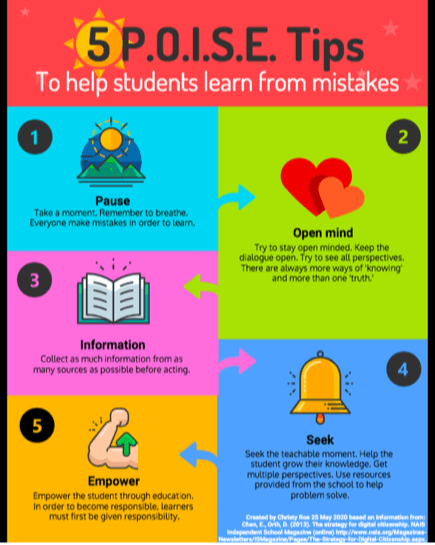

- While at the same time, we must also utilise situations of technology misuse as learning opportunities (see the POISE image below) for the students as well as ourselves as adult digital citizens, setting appropriate boundaries, listening student voices, and continuously encouraging digital literacy and digital citizenship (Chen & Orth, 2013).

- Educators as professionals need to get onboard with 21st century learning and nurture safe, culturally aware, global citizenship and global connections for ourselves as well as for and with our students (Hilt, 2011);

- We must ensure that our digital citizenship curriculum not only protects our students in terms of safety, privacy, copyright, fair use or legality issues, but that it also promotes global cultural, gender, socio-economic status, religion, language and ability awareness and a global appreciation of difference (Hilt, 2011).

- Educators who have embraced the need for global digital citizenship and global connections, need to lead by example and have our own safe, culturally aware, positive and professional ‘brand’ or digital footprint, and we also need to help our students create and tailor their own safe, culturally aware and positive digital footprint ‘brand(s)’ (Neilson, 2012).

- The digital citizenship leadership team, or perhaps even the whole staff, need to hold regular meetings and face to face information and collaboration sessions with families to ensure that preferred means of communication are clarified, that families have input into the digital citizenship program and also so that families are given support in implementing policies, procedures and guidelines at home that suit their individual situation(s) (Chen & Orth, 2013; Levinson, 2010).

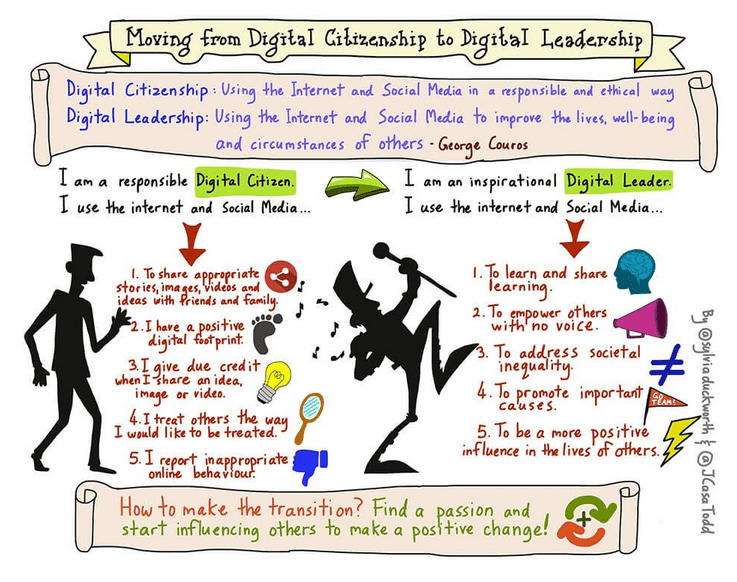

- Finally, the digital citizenship team need to develop a plan to help students move from digital citizenship to digital leadership by creating a technology peer mentorship or student technology leadership program (such as YesK12.org) (Oxley, 2012; TeachThought Staff, 2018).

3. In phase 3, we must implement our plans:

- Prior to students being given devices, we must workshop the digital citizenship expectations, policy, procedures and guidelines that we created in phase 1 & 2 (Cofino, 2012).

“The message is threefold: (1) helping children become good digital citizens must be an ongoing practice led by families and schools together; (2) having access to a range of technology and global connections through school creates a positive context in which to have these conversations; and (3) students will make mistakes, and it’s our collective responsibility to turn mistakes into learnable moments” (Chen & Orth, 2013).

-

Bitmoji Christy ‘Do it!’ Once students begin to utilise digital devices, we must implement the digital citizenship lessons or units of work that we created in phase 2, with a key focus on 21st century learning skills, boundaries, student voice, digital footprints and global connections.

- We must implement the peer mentorship program that we created in phase 2, including student voice in the consequences for unacceptable behaviours (such as the student court, implied by in the slideshow by Cofino, 2012).

- We must continually check in with families, using the resources and communication devices agreed upon in phase 2.

4. And finally, in phase 4, we will reflect and evaluate:

![Growth Coaching International (n.d.) Growth Framework [Image]](https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/croe/files/2020/05/Growth-Coaching-International-n.d.-GROWTH-Framework-Image.jpeg)

List of resources for Teachers and Students:

Policies, procedures or guidelines:

- New South Wales Department of Education and Training’s Policies & procedures > Student use of digital devices and online services (implemented January 27, 2020)

- eSafety Commissioner Teacher Resources;

- State of Victoria (Department of Education & Training) – Consent, Acceptable use agreements and Online services (updated November 2018)

- Sample BYOT Policies http://www.teachthought.com/technology/11-sample-education-byot-policies-to-help-you-create-your-own/

- Sample BYOD Policies http://www.k12blueprint.com/byod

- ‘An overview of school AUP’ written by David Warlick (2008)

- New Zealand Ministry of Education – Digital technology: Safe and responsible use in schools (2015). See also Netsafe.

- Code of Conduct (formerly Digital Citizenship Policy) Garibaldi Secondary School (USA).

- Using digital technologies to support learning and teaching – Victorian State Government, Australia

- Edutopia How to create social media guidelines for your school

- Alberta Canada Social Media Policy for School Districts

Resources for digital citizenship lessons:

- In addition to those recommended in my team’s ETL523 Assessment 2 website, there are also:

5 POISE Tips Infographic PDF by Christy Roe using information from Chen & Orth (2013) - 5 POISE Tips Infographic (shown here) by Christy Roe, based on information from Chen & Orth (2013) for use by both teachers and families

- Common Craft. (2011). Protecting reputations online. http://www.commoncraft.com/video/protecting-reputations-online.

- Common Sense Media. (2010, November 2). Our Connected Culture. http://youtu.be/L0XQj1anI-E

- eSafety Commissioner Cyberbullying resource

- Digital Life Student Intro Video by Common Sense Media, (2010),

- Overexposed

- Attention young professionals! What’s in your digital baggage?

- DontYouForgetAboutMe. (2007, August 11). Everyone – Think before you post (English). http://youtu.be/4w4_Hrwh2XI.

- ‘I Forgot My Phone’ (YouTube | 2:10 mins) | http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OINa46HeWg8 CharstarleneTV. (2013, August 22). I forgot my phone. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OINa46HeWg8.

Examples of global citizenship programs:

- Global Citizen Diploma program

- Lindsay, J. (2009, March 7). Digiteens go global. http://www.slideshare.net/julielindsay/digiteens-go-global (The Digiteens program is no longer running but information is still available about how to implement it).

- Mirtschin, A. (2012, April 26). Hello little world skypers. http://murcha.wordpress.com/2012/04/26/hello-little-world-skypers-group/

- Morgan, L. (2012, March 19). Skype with an astronaut! http://www.frugalteacher.com/2012/03/skyping-with-astronaut.html

- Internet censorship in China [Tag]. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/search?query=internet%20censorship%20in%20china&sort=best

References and further reading

- Beam, C. (2011). Bootleg nation: How strict are Chinese copyright laws? Slate. http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/explainer/2009/10/bootleg_nation.html.

- Chen, E., Orth, D. (2013). The strategy for digital citizenship. NAIS Independent School Magazine (online) http://www.nais.org/Magazines-Newsletters/ISMagazine/Pages/The-Strategy-for-Digital-Citizenship.aspx.

- Cofino, K. (2012, March 24). Digital citizenship: The forgotten fundamental. http://www.slideshare.net/mscofino/digital-citizenship-the-forgotten-fundamental.

- Common Sense Media (n.d.). Lesson in action: Super digital citizen. http://www.commonsensemedia.org/videos/lesson-in-action-super-digital-citizen

- Growth Coaching International (n.d.) Growth Framework [Image] https://www.growthcoaching.com.au/about/growth-approach?country=au

- Hague, C. and Payton, S. (2010). Digital Literacy Across the Curriculum (Futurelab Handbook). Futurelab. https://www.nfer.ac.uk/publications/FUTL06/FUTL06_home.cfm

- Hilt, L. (2011, October 26). The Case for Cultivating Cultural Awareness. http://plpnetwork.com/2011/10/26/the-case-for-cultivating-cultural-awareness/

- James, C., & Jenkins, H. (2014). Disconnected: Youth, New Media, and the Ethics Gap. MIT Press.

- Levinson, M. (2010). From fear to Facebook: One school’s journey. International Society for Technology in Education.

- Lindsay, J. (2016). The global educator: Leveraging technology for collaborative learning and teaching. International Society for Technology in Education.

- Lindsay. J. (2016, July 19). How to encourage and model global citizenship in the classroom. Education Week http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/global_learning/2016/07/how_to_encourage_and_model_global_citizenship_in_the_classroom.html

- Lindsay, J. (2014, March 7). Digital citizenship: A global perspective. http://www.slideshare.net/julielindsay/digital-citizenship-a-global-perspective-reduced-size-32020944

- Lindsay, J. (2015, January 8). Leadership for digital citizenship action. http://www.slideshare.net/julielindsay/leadership-for-digital-citizenship-action-acec-2015

- Michaelsen, A. (2013, October 10). Connected educators for connect learners #ce13. http://annmic.wordpress.com/2013/10/10/connected-educators-for-connect-learners-ce13/

- Mirtschin, A. (2012, January 18). Empowering digital citizenship action. http://murcha.wordpress.com/2012/01/18/empower-digital-citizenship-action/

- Mirtschin, A. (2015, November 4). Talk of the school! https://murcha.wordpress.com/2015/11/04/talk-of-the-school/

- Murray, T. (2013, January 7). 10 steps technology directors can take to stay relevant. http://smartblogs.com/education/2013/01/07/the-obsolete-technology-director-murray-thomas/.

- Nielsen, L. (2012, October 29). 4 things you need to know to help your students manage their online reputation by. http://theinnovativeeducator.blogspot.co.uk/2012/10/4-things-you-need-to-know-to-help-your.html.

- Ohler, J. (2011). Character education for the digital age. ASCD Educational Leadership. 68(5). http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/feb11/vol68/num05/Character-Education-for-the-Digital-Age.aspx.

- Oxley, K. (2012, August 12). Developing a digital citizenship program. http://www.slideshare.net/cathryno/developing-a-digital-citizenship-program.

- Pashiardis, P. (1996). Environmental scanning in educational organizations: uses, approaches, sources and methodologies. International Journal of Educational Management, 10(3), 5-9.

- Ribble, M.(2011). Digital citizenship in schools. International Society for Technology in Education.

- Sheninger, E. (2017, August 29). 7 pillars of digital leadership in education. https://www.teachthought.com/the-future-of-learning/7-pillars-digital-leadership-education/

- TeachThought Staff (2018, November 18). Moving students from digital citizenship to digital leadership. https://www.teachthought.com/the-future-of-learning/moving-students-from-digital-citizenship-to-digital-leadership/

- Tiven, M. E., Fuchs, E., Bazari, A., & MacQuarrie, A. (2018). Evaluating global digital education: Student outcomes framework. New York, NY: Bloomberg Philanthropies and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

How should educators design / develop / create / manage a digital learning environment (DLE)? (ETL523 Modules 3-5)

Why create a quality DLE?

The reasons behind and processes for creating a quality DLE is much like creating a ‘Learning Commons,’ (which I’ve discussed in two previous posts from ETL503 Resourcing the Curriculum: click here and here).

How do we create a quality DLE?

The article from Chen & Orth (2013) is absolutely amazing, not only because it points out that we must link the school DLE to the home DLE, but also because they outline the key steps to creating a quality DLE starting with 1. forming a group  of stakeholders, creating a shared vision and core beliefs, then 2. training, communicating with or informing all stakeholders, followed by 3. implementing the DLE plan of lessons and concepts of digital citizenship and digital literacy, completing the circle by 4. evaluating and reviewing the DLE regularly.

of stakeholders, creating a shared vision and core beliefs, then 2. training, communicating with or informing all stakeholders, followed by 3. implementing the DLE plan of lessons and concepts of digital citizenship and digital literacy, completing the circle by 4. evaluating and reviewing the DLE regularly.

How do we manage the DLE to foster globally connected learning?

As recommended by Lindsay (2016), we need to:

- Discuss the digital footprints or ‘branding’ of all students and make sure they are using long-term appropriate and culturally sensitive language and images.

- Consider the digital divide and make sure that platforms, discussion tools and global or local connections are provided synchronously (in real time) and asynchronously (offline or pre-recorded).

- Create a DLE that offers students opportunities to authentically and collaboratively engage with peers globally. (Lindsay, 2016).

How can we manage the DLE to move students from social media citizens to social media leaders?

References

Casa-Todd, J. (2016). Rethinking Student (Digital) Leadership and Digital Citizenship [Image]. Retrieved from: https://jcasatodd.com/rethinking-student-digital-leadership-and-digital-citizenship/

Lindsay. J. (2016, July 19). How to encourage and model global citizenship in the classroom. Education Week. Retrieved from http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/global_learning/2016/07/how_to_encourage_and_model_global_citizenship_in_the_classroom.html

Chen, E., Orth, D. (2013). The strategy for digital citizenship. NAIS Independent School Magazine (online) http://www.nais.org/Magazines-Newsletters/ISMagazine/Pages/The-Strategy-for-Digital-Citizenship.aspx.

![Hague, C., & Payton, S. (2010). Digital literacy across the curriculum [Handbook [Image]. pp. 19.](https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/croe/files/2020/05/Hague-C.-Payton-S.-2010.-Digital-literacy-across-the-curriculum-Handbook-Image.-BECTA-FutureLab.-pp.-19.-National-Foundation-for-Educational-Research-httpswww.nfer_.ac_.uk-publicationsFUTL06FUTL06.pdf.png)