Part A – Personal Philosophy

What makes an effective Teacher Librarian?

An effective Teacher Librarian (TL) is an information specialist, resource curator, and an educational programmer who advocates, develops, and supports lifelong learning of students, colleagues, and wider school communities. As a TL, it is my aim to foster a space that engages, empowers, challenges, and grows my patrons through collaboration, developmental opportunities, and the provision of a quality collection. As a TL, I also value trustworthiness, inclusivity, accessibility, and diversity. I believe that a TL must advocate for the importance of libraries as hubs for positive social change; as seen through freedom of access, restricting censorship, fostering intellectual freedom, and encouraging individual creativity.

Part B – Themes

1: Children’s Literature

Children’s literature emerged in the first half of the 20th Century during a time of information and recreational scarcity (Fasick, 2011, p. 1). Now in the 21st Century, children’s literature is readily accepted as an important educational tool for supporting language development and creativity amongst young readers (Bayraktar, 2021, p. 342). However, discourse has arisen as to what characterises quality children’s literature, the methodology involved in resourcing such literature, and the implications surrounding its acquisition. During my professional placement at the Ipswich Children’s Library (ICL), and my studies of ETL503, I have been able to explore the discourse surrounding quality literature resourcing from both practical and theoretical viewpoints.

In a general sense, quality literature is widely regarded as having rich language, powerful imagery, strong characters and plot, levels of complexity and meaning, opportunities for the exploration of literary devices, and conceptual textuality which develops deep, critical, and emotional ways of thinking. Simpson (2016), characterises quality literature as texts that promote sensory awareness, develop emotional sensitivity, and provide a rich linguistic environment (p. 27); whilst Krashen (2004) states that quality literature not only encourages deeper comprehension, but it also stimulates richer vocabulary development. Bayraktar (2021) concurs, adding that quality literature not only improves linguistic, emotional, and cognitive skills, but also conveys cultural and social messages (p. 343-345). Through this I have come to surmise that quality literature is rich in language, that goes beyond storytelling to explore social, emotional, and cognitive themes, for reader enjoyment and their academic development. Within the context of being a TL, I must also consider how quality literature is resourced with the learning needs of my students, teachers, and wider community at the foremost.

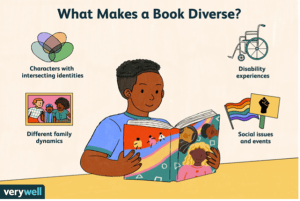

When selecting resources for school libraries, a TL must select literature that not only meets the interests and learning needs patrons, but also meets curriculum needs (ETL503). When selecting quality literature for primary schools, resources must align with the cognitive, emotional and linguistic abilities of patrons, be free of bias, be age-appropriate, enhance reader engagement, encompass appealing characters, settings and storylines, share a variety of values or diverse themes, provide accurate information, encourage reading skills and strategies (i.e., inferencing), implement authentic language, reflect social change, support educational expectations, and provide opportunities for making connections and building understanding (ADL, 2006). It is also important that context (e.g., socio-economic, cultural, religious, gender) is considered when selecting quality literature. In ETL503, we were taught the importance of selecting quality resources as TLs, and how identifying and evaluating resources determines their relevance. The following criteria (Picture 1) enables a TL to select quality literature that is learner focused and suited to specific contexts (e.g., curriculum).

Picture 1 Quality Resourcing: Selection Criteria (Harris, 2023)

Additionally, through my professional placement at the ICL, I also learnt about the importance of ‘mirror’, ‘window’ and ‘sliding glass door’ texts within children’s literature (briefly within my Professional Placement Report). These types of quality texts enable readers to make text-to-self, text-to-other, and text-to-world connections as ‘mirror’ books allow students to see their life or selves within literature, and ‘window’ books allow students to learn about the lives of others; while ‘sliding glass door’ books expand on window books through encouraging reflection and action (WeAreTeachers Staff, 2018). ADL (2006) agreed on the importance of such literature, commenting that quality children’s literature can act as a powerful vehicle for understanding and celebrating diversity whilst challenging prejudice, stereotypes, and discrimination.

Picture 2 Mirror, Window, and Sliding Doors (Smith, n.d.)

Picture 3 What Makes a Book Diverse (Verywell, Catharine Song, n.d.)

It is also important to note, that TL’s face many limitations and barriers when resourcing quality literature, which can include budget restrictions, time constraints, physical library space and storage, competing demands, crowded curriculum, misdirected motivation, and lack of student, staff, or community engagement (Merga, 2019, p. 70).

As a TL, I will strive to overcome hurdles and utilise the above criteria to resource a quality library collection that supports curriculum needs, teaching and learning practises, and the interests and experiences of my students. With continued reflection, evaluation, and professional development, I aim to resource a library boasting quality literature; as choosing resources that qualify as such are important in the development and learning of young readers, as they are affected and informed by the quality of the books that they read; which may have lasting effects on their education and identity (Bayraktar, 2021, p. 344).

2: Information Literacy

Today’s children are growing up in a digital world where technology and related medias are changing and advancing at an unprecedented rate (Harrison & McTavish, 2018, p. 163). Now exposed to digital technologies from birth, our students have regular access to new forms of literacy. These literacies are no longer confined to traditional text, but now encompass symbolic, technological, and multimodal ways of meaning making that combine printed text, music, visuals, animations, hyper-text, and sounds (Harrison & McTavish, 2018, p. 164). These new forms of literacy are predominantly referred to as Information Literacy (IL) but can subsequently be known as media-literacy, trans-literacy, meta-literacy, information fluency or digital literacy.

Picture 4 A Brief Evolution of Books (Kogan, n.d.)

The concept of IL was introduced in the 1970’s by Zurkowski (1974); but it wasn’t until the 1990’s that the term become more readily used (Herring & Bush, 2009, p. 2). Within today’s digital culture, students are now engaging with both physical and digital spaces to consume, create, socialise, and communicate with information; however, the definition of IL is still widely debated, unlike traditional literacy which can be universally defined due to its longevity, linearity, and stability. In short, it is aggreged upon that, IL holds a focus on developing one’s technical skills and abilities so that they can participate wholly in a digital society (Erstad et al., 2019, p. 172). IL can also be characterised by the skills of defining, navigating, locating, selecting, organising, presenting, and evaluating information in a variety of forms for personal, educational, social, or global purposes (Herring & Bush, 2009, p. 3).

Through units ETL401 and INF533, I have been able to explore IL from a theoretical standpoint; whilst working with the Programming team at the ICL has enabled me to observe how effective IL can be practically applied. During ETL401, I came to appreciate my students as digital learners who are living and working within information landscapes. These digital landscapes require students to be able to recognise when information is needed and to have the capacity to locate, evaluate, and use the information effectively (Fitzgerald, 2015). Yet, we assume that all children are born digital-natives and can understand and correctly implement these digital skills; this is not always the case. Many researchers have found, that despite most children approaching IL more confidently than adults do, that these children do not necessarily have the skills required for effective information retrieval (Walter, 2000, p. 79). Therefore, it is the responsibility of educators and TLs to help children to become confident and critical thinkers and users of IL (Armstrong, 2008, p. 11). One-way educators can do this is through implementing scaffolding IL initiatives such as the Big 6, The Seven Pillars of Information Literacy, Guided Inquiry, and The Information Search Process.

Picture 5 The Big 6 (VGU Lib Guide, n.d.)

Picture 6 SCONUL Seven Pillars (Stewart, 2016)

On placement, I was able to observe a modified IL initiative in action. Here, the library implemented an adapted version of the Big 6, with the aim of helping younger patrons locate, access and use information autonomously and effectively. In a general sense, they achieved this through creating child-friendly directories, catalogues, and library website, as well as providing support for the use of Libby, Borrow Box, Kinderling Kids, and Kanopy Kids. More specifically, the STEAM and Makerspace teams utilised the Big 6 and Inquiry Process to guide children through their learning experiences, equipping them with information literacy skills (and much more).

In a school setting, it is advised that IL permeate the whole school and not be limited to just the library; with Herring and Bush (2009) identifying that collaboration between TL and teachers is key in developing information literate and digital citizens (p. 9). As an educator and TL, I will aim to collaborate with my colleagues to “bridge the gap” between inquiry, information, and digital skills of my students (Lupton, 2012).

Picture 7 Ipswich Children’s Library Catalogue (Brisbane Kids & Bride, n.d.)

When studying INF533, I was able to draw parallels between the IL seen within ETL401 and how students read digitally born texts, such as e-books, e-stories, linear and non-linear e-narratives, interactive stories, hyper-textual and hyper-media narratives, and electronic games (Walsh, 2013, p. 183). Like IL, digital texts utilise a mix of traditional print, maps, hyperlinks, animation, moving images, sounds, text augmentation, videos, and music (Yokota & Teale, 2014, p. 579-580); they also require students to have sound aesthetic sensitivities, critical and creative thinking, and multiliteracy skills to access and understand information (Chung, 2008, p. 22). Just like with IL, educators much teach students the specific skills needed to successfully use digital texts. As reflected upon in INF533 Assignment 4, digital storytelling is becoming a staple within schools. Therefore, implementing rich, purposeful, and appropriate digital tools is of the uttermost importance; as effective implementation strongly correlates with positive student motivation, engagement, language skills, critical and creative thinking, and socialising (Yang & Wu, 2015, p. 340).

Like many other models of teaching, the implementation of IL is prone to limitations and challenges, such as funding, time constraints, group sizing, scaffolding restraints, lack of collaboration or support, unattainable expectations, or insufficient training (Fitzgerald & Garrison, 2017). Additionally, with the technology boom cyber safety has emerged, which means that educators must explicitly teach net-etiquette so that students remain safe when utilising information and digital literacy (Armstrong, 2008, p. 181). Armed with the above knowledge, I aim to equip all my students to be information and digitally literate learners.

3: Intellectual Freedom and Censorship

The Australian Library and Information Association (ALIA) state, that they aim to promote the free flow of information and ideas for all Australians; and that they do not support censorship (2023). Also known as intellectual freedom, this free flow of information is essential to civil society (Doyle, 2002, p. 17); and is identified as the right to access and share information without stipulation; as fair and prosperous society is built off the free access of information, and the ability to develop understanding and communicate without bounds (CILIP, n.d.). The International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) calls for libraries to adhere to the principle of intellectual freedom, uninhibited access to information, freedom of expression, and the discretion of the library user (2007); however, one major challenge rising against this is censorship.

Picture 8 Support Intellectual Freedom (Nhernandez, 2022)

Censorship is infamously hard to define; but in simple terms it is characterised by the restriction of free information (Duthie, 2010, p.86). Information that is censored usually falls into one of four categories: political, sexual, social, or religious; and can be used to supress the voices or opinions of specific groups (Oppenheim & Smith, 2004, p. 161). Within the context of libraries, censorship can appear in overt and covert ways (Moody, 2005, p.145). On an overt level, censorship can appear as particular communities or organisations “safeguarding” information from those they perceive to be vulnerable, or by removing information they deem against their values, morals, or religions (Duthie, 2010, p.86). Whilst on a covert level, censorship within libraries can include legal issues (e.g., copyright, hate material, pornography), vendor and publisher bias, acquisitions outsourcing, citation rates for periodical selections, pressure from funding bodies, reduced visibility of independent publications, labelling of controversial items, and inaccurate or slow cataloguing/ classification (Moody, 2005, p. 140-145). Censorship primarily effects collection management, in particular the processes of selection, accessibility, and cataloguing (Oppenheim & Smith, 2004, p. 159). However, the battle between libraries and censorship has been a long and troublesome one and will continue to be so (Hannabuss & Allard, 2001, p. 81).

Picture 9 Censorship (Hinton & Tuchman, 2019)

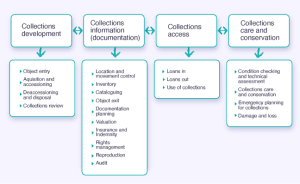

During ETL503, we learnt about collection development policies (CDP) and how they act as a precaution against censorship or as an advocate for it. A CDP acts as a tool that underpins the function of the library; in alignment with the library’s strategic direction, the CDP provides purpose to the collection and ultimately the direction of the library (ALIA, 2007, p. 3). Having a clear CDP assists librarians in managing problems such as censorship and copyright, as the policy provides a unified voice on how they should be handled and even resolved (Oberg & Schultz-Jones, 2015, p. 33-34). During placement, I was able to witness first-hand how a CDP can be used to act against censorship when working with the Collection Management and Logistics team; as the library was facing opposition for the graphic novel ‘Gender-Queer’ within the main branch. In their CDP, it is stated that they uphold the civic values of access, diversity, equity, and inclusion; whilst explicitly commenting that they endeavour to provide an unbiased and balanced collection (print and digital) that responds to the board needs of the community (City of Ipswich, 2019-2023, p. 2). The CDP also states that all collection materials must comply with State and Federal Laws. Through this firm CDP, the team was able to justify the novels inclusion within the collection. However, it was decided upon that the book must be labelled with a warning sticker (i.e., mature content). Personally, I believe that it is the librarian’s responsibility to refuse such labelling on the grounds of it subduing intellectual freedom (Moody, 2005, p. 145). Regardless of whether the material is controversial, librarians are called to resist obstructing (labelling) the free flow and access to information (Jaeger et al, 2015, p.168-169).

Picture 10 Collection Development Policy (Collections Trust, n.d.)

On top of the CDP, it is also the librarian who must be responsible when it comes the resisting censorship; however, selection censorship does occur when libraries decide against materials, even when they meet the requirements of the CDP (Oppenheim & Smith, 2004, p. 164). This often occurs because of self-censorship or restrictions based upon perceived community standards (Moody, 2005, p. 142). To counteract self-censorship and non-selection, I will aim to put my personal bias aside and educate myself thoroughly through professional development opportunities; so that my library can facilitate growth and understanding with regards to diversity and inclusivity. As the contemporary understanding of librarians, is that they should take a professional stance of anti-censorship (Moody, 2005, p. 145). Through free and uncensored information, I can prepare my students to work effectively in diverse and inclusive environments; where race, ethnicity, gender, socio-economic status, education, ability, language, literacy, geography, and orientation are represented equally (Jaeger et al., 2015, p. 127). It is my role as a TL, to assist my students in safely and wisely using the collection through utilising skills such as information literacy and digital safety, which allow them to navigate, select, access, use, and evaluate materials appropriately.

Part C – ALIA Aligned Reflection

Standard 1.1 and 3.1 underpin the principals of lifelong learning, which were explicitly taught to me throughout my studies and carried into my pedagogy as a classroom teacher (ALIA, 2004). Throughout ETL401 and INF533, I have learnt that an effective Teacher Librarian (TL) must be well-informed of current information literacy, thoroughly understanding how learners develop and apply lifelong learning skills and strategies; and how comprehensive understanding of information and communication technologies (ICTs) can promote lifelong learning.

Through ETL402 and ETL503, I was able to explore how a TL must hold a detailed and current educational pedagogy, be thoroughly familiar with information literacy skills and the interests of their learners, and cater to the social, cultural, and developmental needs of their learners (ALIA, 2004, Standard 1.2). Through ETL503, ETL504, EER500 and INF533 and with my placements Collection Management and Logistic (CML) team, I was able to develop a comprehensive understanding of how children’s literacy and literature can promote and foster reading, and how this understanding can also inform specific programs and curriculum needs within schools. These experiences also allowed me to develop my specialist knowledge of information, resources, technology, and library management (ALIA, 2004, Standard 1.4). Consequently, I am now able to understand that professionally managed and resourced libraries, alongside a positive reading culture, actively promote rich literature (ALIA, 2004, Standard 3.2).

Whilst on professional placement, I was able to see Standards 2.1 and 2.2 in action; where I observed how supportive, and information-rich learning environments can engage and challenge learners, and how collaborative planning and programs are designed to incorporate transferable information literacy skills through cleverly crafted programs (ALIA, 2004). Similarly, ETL504 and ETL401 enabled me to explore how an exemplary TL provides library and information services consistent with the national standards and aligned with the school’s mission, community focus, and patrons needs (ALIA, 2004, Standard 2.3). Additionally, through meeting with the CML team I was able to see how strategic planning and budgeting can be streamlined to improve information services and programs, as well as experiencing some of the pitfalls and obstacles that may be encountered (i.e., censorship), and how this all informs professional practice.

Standard 3 encourages TLs to develop their professional knowledge and experience in ways that demonstrate commitment to lifelong learning, professional service, collaboration, and transformational leadership (ALIA, 2004). During my time at the Ipswich Libraries, and informed by the theory of ETL504, I was able to actively participate as a member of a professional community and demonstrate collegiality through commitment to professional practice and through my participation to collaborative teams. I was also able to share my expertise in a way that extended and promoted the libraries services (i.e., utilising my L3 training).

At the end of each unit, we are encouraged to reflect upon our studies and professional experiences thus far, leading us to become reflective practitioners. We are also encouraged seek out areas for professional development; for myself I have chosen to seek out further training in library management and logistics, as I thoroughly enjoyed contributing to these teams on placement. I also aim to research and reflect more upon censorship and the right to intellectual freedom (perhaps even write a passion paper). Ultimately, I have thoroughly enjoyed the journey of my Master of Education (Teacher-Librarianship) and cannot wait to put all my skills and theory into practice.

word count: 3151/3000 +/-10%

Reference List

ADL (2006). Tools and Strategies: Accessing children’s literature. https://www.adl.org/resources/tools-and-strategies/assessing-childrens-literature

ALIA, Australian Library and Information Association (2004). Standards for Professional Excellence for Teacher Librarians. https://read.alia.org.au/alia-asla-standards-professional-excellence-teacher-librarians

ALIA, Australian Library and Information Association (2007). Library Collection Development Policy Templet.https://www.alia.org.au/common/Uploaded%20files/ALIA-Docs/Communities/ALIA%20Australian%20Government%20Library%20and%20Information%20Network/library_collection_development_policy_template.pdf

ALIA, Australian Library and Information Association (2023). What We Do. https://www.alia.org.au/Web/Web/About-Us/What-we-do.aspx

Armstrong, Dr. S (2008). Introduction to Information Literacy. Teacher Created Materials Publishing, United States. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/CSUAU/reader.action?pq-origsite=primo&ppg=12&docID=408103

Bayraktar, A (2021). “Value of Children’s Literature and Students’ Opinions Regarding Their Favourite Books” in the International Journal of Progressive Education, vol. 17, no. 4, 2021. DOI: 10.29329/ijpe.2021.366.21

Brisbane Kids (n.d.) Ipswich Children’s Library review. https://brisbanekids.com.au/ipswich-childrens-library-review/

Bush, S.J. & Herring, J. (2009). Creating a Culture of Transfer for Information Literacy Skills in Schools. ASLA Inc. https://researchoutput.csu.edu.au/en/publications/creating-a-culture-of-transfer-for-information-literacy-skills-in

CILIP (n.d.). Freedom of Access to Information. https://www.cilip.org.uk/page/FreedomOfAccessToInformation

Charles Sturt University (n.d.) EER500: Introduction to Educational Research. Interact 2: https://interact2.csu.edu.au

Charles Sturt University (n.d.) ETL401: Introduction to Teacher Librarianship. Interact 2: https://interact2.csu.edu.au

Charles Sturt University (n.d.) ETL402: Lit Across the Curriculum. Interact 2: https://interact2.csu.edu.au

Charles Sturt University (n.d.) ETL503: Resourcing the Curriculum. Interact 2: https://interact2.csu.edu.au

Charles Sturt University (n.d.) ETL504: Teacher Librarian as Leader. Interact 2: https://interact2.csu.edu.au

Charles Sturt University (n.d.) INF533: Literature in Digital Environments. Interact 2: https://interact2.csu.edu.au

City of Ipswich (2023). Collection Development and Logistics Statement: Procedure. Ipswich City Council.

City of Ipswich (2019-2023). Library Services Policy. https://www.ipswich.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/86032/Library-Services-Policy.pdf

Chung, S. K. (2007). Art education technology: Digital storytelling. Art Education (Reston), 60(2), 17–22., https://doi.org/10.1080/00043125.2007.11651632

Collections Trust (n.d.). Collections Development Policy. https://collectionstrust.org.uk/accreditation/managing-collections/holding-and-developing-collections/collections-development-policy/

Doyle, T (2002). “Selection Versus Censorship in Libraries”, In Collection Management, vol. 27, no. 1, 2002, pp. 15–25. https://doi.org/10.1300/J105v27n01_02

Duthie, F (2010). “Libraries and the Ethics of Censorship”, in The Australian Library Journal, vol. 59, no. 3, 2010, pp. 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049670.2010.10735994

Erstad, O, et al (2019). The Routledge Handbook of Digital Literacies in Early Childhood. Routledge, 2019. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/CSUAU/detail.action?pq-origsite=primo&docID=5812516

Fasick, A (2011). From Boardbook to Facebook: Children’s services in an interactive age. Libraries Unlimited, 2011. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/CSUAU/detail.action?docID=729873&pq-origsite=primo

Fitzgerald, L (2015). “Guided inquiry in practice”, in Scan, vol. 34, no. 4, p. 16-27. https://search-informit-org.ezproxy.csu.edu.au/doi/10.3316/AEIPT.211651

Garrison, K. & Fitzgerald, L (2017). “‘It rains your brain’: Student reflections on using the guided inquiry design process”, in Synergy (Carlton, Vic.), vol. 15, no. 2, 2017.

Harris, M (2023). Infographic: Quality Resourcing. Image.

Harrison, E. & McTavish, M (2018). “I’Babies: Infants; and toddlers’ emergent language and literacy in a digital culture of iDivices”, in Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, vol. 18, no. 2, 2018, p. 163-188. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798416653175

Hannabuss, S & Allard, M. “Issues of censorship”, in Library Review (Glasgow), vol. 50, no. 2, 2001, pp. 81–89, https://doi.org/10.1108/00242530110381127

Hinton, M (2019). For Librarians, Banned Books Week is a Chance to Discuss Censorship, Intellectual Freedom with Students. Image by Mark Tuchman. https://www.slj.com/story/For-Librarians-Banned-Books-Week-Is-a-Chance-To-Discuss-Censorship-Intellectual-Freedom-With-Students

International Federation of Library Associations and Institutes (2003). IFLA Statement on Libraries and Intellectual Freedom. https://www.ifla.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/assets/faife/presen.pdf

Jaeger, P. T., et al. (2015). “Diversity, Inclusion, and Library and Information Science: An Ongoing Imperative (or Why We Still Desperately Need to Have Discussions about Diversity and Inclusion)”, in The Library Quarterly (Chicago), vol. 85, no. 2, 2015, p. 127–132, https://doi.org/10.1086/680151

Krashen, S (2004). The Power of Reading: Insights from research. Heinemann, Portsmouth, NH. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/CSUAU/detail.action?pq-origsite=primo&docID=4543924

Kogan, C. (n.d.). A Dilemma of Choosing the Right Book from Billions of Options. https://constkogan.medium.com/a-dilemma-of-choosing-the-right-book-from-billions-of-options-58ebcced4d02

Lupton, M. (2012). Inquiry skills in the Australian curriculum. Access, 26(2), 12-18. Retrieved from https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.csu.edu.au/docview/1026808273?accountid=10344

Merga, M (2019). “School libraries fostering children’s literacy and literature learning: mitigating the barriers”, in Literacy (Oxford, England), vol. 45, no. 1, 2020, p. 70-78. https://doi.org/10.1111/lit.12189

Moody, K (2005). “Covert Censorship in Libraries: A Discussion Paper”, in The Australian Library Journal, vol. 54, no. 2, 2005, pp. 138–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049670.2005.10721741

Nhernandez (2002). Support Intellectual Freedom: Read banned books. Image. https://smcl.org/blogs/post/support-intellectual-freedom-read-banned-books/

Oberg, D. & Schultz-Jones, B. (eds.). (2015). ‘Collection management policies and Procedures’, in IFLA School Library Guidelines, (2nd ed.), p. 33-34. https://www.ifla.org/files/assets/school-libraries-resource-centers/publications/ifla-school-library-guidelines.pdf

Oppenheim, C. & Smith, V (2004). “Censorship in libraries”, in Information Services & Use, vol. 24, no. 4, 2004, pp. 159–170, https://doi.org/10.3233/isu-2004-24401

Simpson, A (2016). “Choosing to teach with quality literature: from reading (through talk) to writing”, in Scan (North Sydney, N.S.W), vol. 35, no. 4, 2016, p. 26-38. https://search-informit-org.ezproxy.csu.edu.au/doi/abs/10.3316/informit.369764072654441

Stewart, I. (2016). SCONUL 7 Pillars. Image. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/SCONUL-7-pillars-model_fig9_305752043

Smith, A (n.d.). Infographic: Windows, Mirrors and Sliding Glass Doors. Teachers Pay Teachers. Image. https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/FreeDownload/Windows-Mirrors-and-Sliding-Glass-Doors-Infographic-9085251

Verywell & Song, C (n.d.). What Makes a Book Diverse. Image. https://www.verywellmind.com/the-importance-of-representation-5076060

VGU Lib Guide (n.d.). Big 6: Information Literacy Model. Image. https://vgulibguide.wordpress.com/info-literacy-skills/big6-model/

Walsh, M. (2013). Literature in a digital environment (Ch. 13). In L. McDonald (Ed.), A literature companion for teachers. Primary English Teaching Association Australia (PETAA). https://doms.csu.edu.au/csu/file/863c5c8d-9f3f-439f-a7e3-2c2c67ddbfa8/1/ALiteratureCompanionforTeachers.pdf

Walter, V. A. (2000). Children and Libraries: Getting It Right. American Library Association, 2001. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/CSUAU/detail.action?pq-origsite=primo&docID=3001647

We are Teachers Staff (2018). What are Mirrors, Windows, and Sliding Glass Doors. https://www.weareteachers.com/mirrors-and-windows/

Yokota, J. & Teale, W. H. (2014). Picture books and the digital world: educators making informed choices. The Reading Teacher, 34(6). https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1262

Yang, Y-T, C., & Wu, W. Digital Storytelling for Enhancing Student Academic Achievement, Critical Thinking, and Learning Motivation: A Year-Long Experimental Study. Computers and Education, vol. 59, no. 2, 2012, 339–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.12.012