Tag: Resource Selection

Information and society – Reflection on INF506 Module 2

OLJ Task 2: The influence of technology on society or OLJ Task 3: Reflections on the impact of change

To be or not to be (active on social media) is no longer the question

If we want ‘customer-driven, socially rich, and collaborative model of service and content delivery’ (module 2) then we must stop asking ‘why’ or ‘when’ and start asking ‘how.’

If we want ‘customer-driven, socially rich, and collaborative model of service and content delivery’ (module 2) then we must stop asking ‘why’ or ‘when’ and start asking ‘how.’

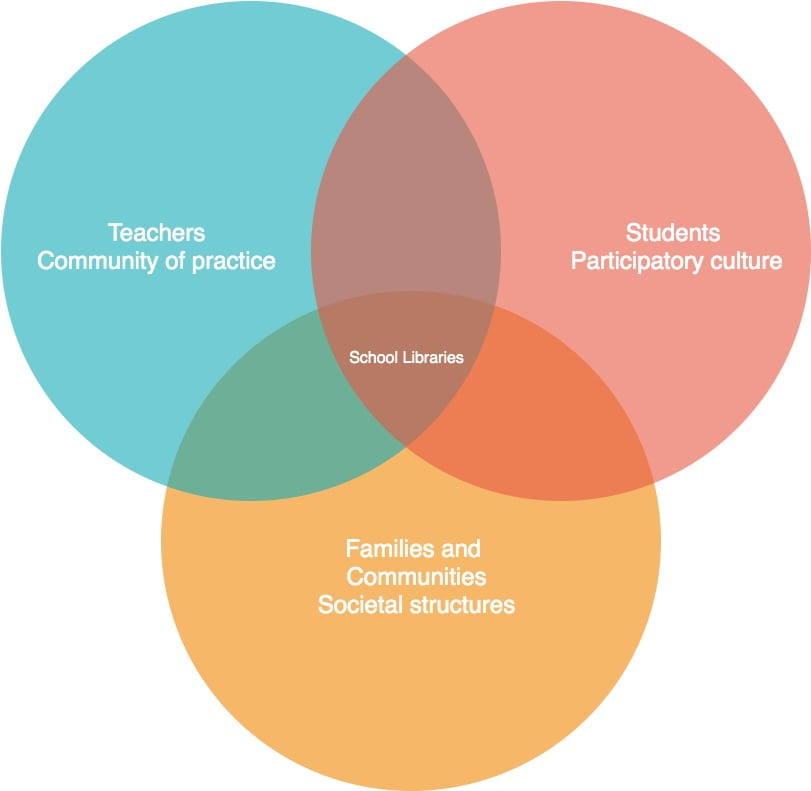

Why do we expect teachers to have a work culture aiming for a ‘community of practice’ (which I’ve discussed at length in previous blog posts, but also mentioned by Nisar, Prabhakar, G & Strakova, 2019), however, conversely, we expect students work almost entirely independently? Today’s working society has shifted, and so too has kid culture. Just as work places are becoming communities of practice, 21st century students have a participatory culture (also discussed in previous blog posts).

Jenkins, Clinton, Purushotma, Robison & Weigel (2006, p.3) define a participatory culture as: “a culture with relatively low barriers to artistic expression and civic engagement, strong support for creating and sharing one’s creations, and some type of informal mentorship whereby what is known by the most experienced is passed along to novice. A participatory culture is also one in which members believe their contributions matter and feel some degree of social connection with one another (at least they care what other people thing about what they have created).”

According to Jenkins (et al., 2006), forms of participatory culture could include affiliations, expressions, collaborative problem-solving and circulations [“Affiliations – memberships, formal and informal, in online communities centred around various forms of media, such as Friendster, Facebook, message boards, meta-gaming , came clans or MySpace); Expressions – producing new creative forms, such as digital sampling, skinning and modding, fan video-making, fan fiction writing, zines, mash-ups); Collaborative Problem-solving – working together in teams, formal and informal, to complete tasks and develop new knowledge (such as through Wikipedia, alternative reality gamine, spoiling); or Circulations – shaping the flow of media (such as podcasting, blogging).”]

Artega (2012, p.72) writes, “social media extends the social milieu to the digital sphere where opportunities for global social participatory learning are plentiful.” Thus, to be viable in today’s globally connected society, particularly in western civilisation where a participatory culture has become the ‘norm,’ an educational facility’s social media presence is not only something that is necessary, but is something that must be done effectively.

“For library managers, questions are moving beyond how to initiate and launch social media to the more challenging problem of how to do social media well— how to better integrate social media into the life of the library, how to more fully engage the library’s staff and users in social media; how to make the library’s social media more effective in outreach and delivery of services, and how to measure the library’s presence and activities within social media in ways that truly matter. The next wave of trends in social media use are also always looming on the horizon— what will be the next big social site where users will be going next within the social media landscape, and should the library follow?” (Mon, 2014, p.51).

Some purposes for social media have been suggested by Mon (2014, p.24) as supported by the research of AlAwadhi (2019) to include: increased avenues for feedback from users, promotion and advocacy of the school &/or library, improved information access through outreach programs, deliverable educational or support hubs, improved collections and stronger or more frequent global collaborations. Notably, Kwon’s (2020) research places building trust ahead of information motivation as a reason for use of community social media platforms.

Roadblocks to consider

There is also the issue of needing to be innovative in the types of platforms that we promote as educators (as supported by the research of Manca (2020). Which brings up another roadblock to implementing social media for schools is the fact that there is an age limit for access – most students in K-6 Australian educational settings are below the age of 13 and cannot be encouraged by educators to look at nor participate in most social media applications. This means we have to tailor our content to an older demographic and seek out other (less public) social media platforms for younger students.

Some additional roadblocks or things to consider have been provided by Business.gov.au (2019) and they are to have a clear social media strategy, be mindful that additional staff or resources may be required for daily monitoring of all online platforms, be prepared for inappropriate behaviour (bullying, harassment, negative feedback, misleading or false claims, copyright infringement, information leaks or hacking) and have an action plan ready within your policy documents detailing specifically how to deal with these instances prior to launch date(s).

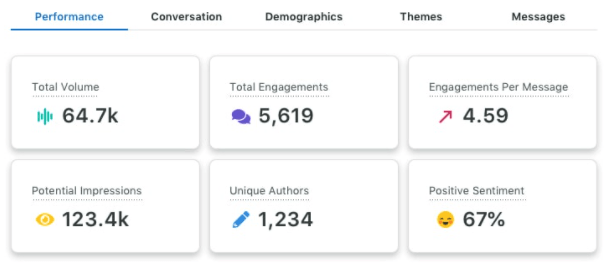

Hicks, Cavanagh & VanScoy (2020) recommend monitoring a library’s online presence via a ‘social network analysis (SNA).’ The SNA is a ‘theoretical framework and quantitatively oriented methodology’ for libraries to understand their ‘big data stories’ or connections with their community identifying relevant patterns and relationships among individuals, groups, or organisations over a specified period of time.

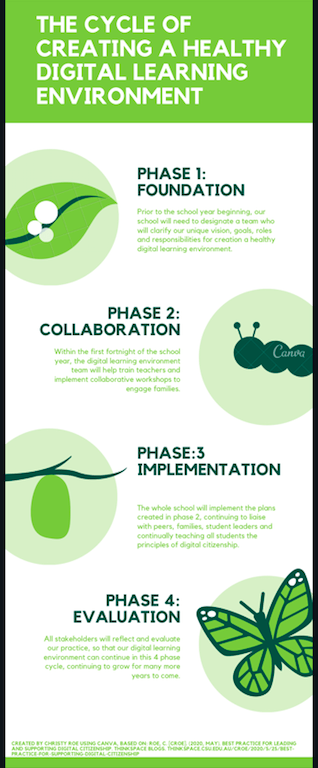

All of these issues need to be incorporated into the digital learning environment creation plan, a four phase process that I’ve detailed in a previous blog post from Digital Citizenship, but that can best be summarised in this infographic:

How to design a platform and design it well, improving engagement (web 2.0)

This leads to the next issue – how to have a website (web 1.0), that is interactive (web 2.0) and makes the step towards linking the online world to the offline world (web 3.0). We need to be thinking beyond web 1.0 in terms of having a simple ‘face’ website that offers little to no interaction and does not enable, encourage (nor monitor) engagement but a platform, website and social media presence that actively engages our users. The web 2.0 model of ‘likes’ is also becoming an outdated model and with web 3.0 we must begin to think of our digital presence as fully interactive, including building meaningful ongoing connections (Barnhart, 2020).

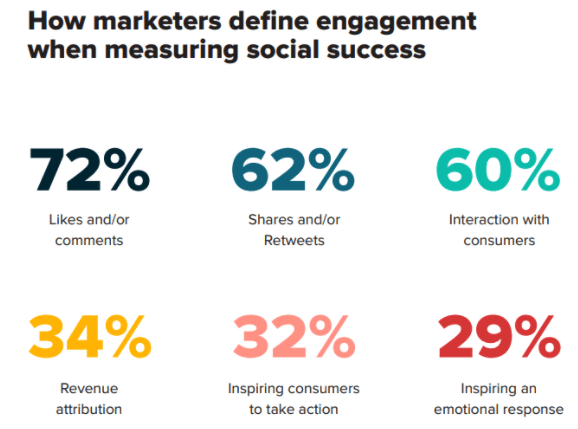

But each context must first ask “what does it mean to have ‘engaged users?” and “what platforms / website / social media should we use to engage them?”

After my practical work-placement in a local public library, where I completed two weeks of ‘virtual’ research on website design (offering several recommendations for website development for the library), I realise that there are almost infinite resources, research and opinions on how to design effective websites. I don’t believe that my understanding of moving from the web presence currently (as web 1.0) to web 2.0 (more interactivity) to even web 3.0 (content creation by the users) was fully developed, until I watched the video provided in module 2 of INF506 (Schwerdtfeger, 2013). I wish I had been able to communicate this idea previously.

Yet, one key article that I did find, in the interest of brevity, was Garett, Chiu, Zhang & Young’s (2016, p.1) literature review on website design in terms of user engagement. Their 4 notable findings were:

- “Websites have become the most important connection to the public and using social media links on websites may increase user engagement;

- Proper website design is critical for user engagement, because poorly designed websites result in a higher user ‘bounce’ rate (users do not proceed past the home page) whereas, well designed websites encourage user exploration and revisit rates;

- The International Standardised Organisation (ISO) (in Garett, et al., 2016, p.1) defines website ‘usability’ as: “the extent to which users can achieve desired tasks (e.g., access desired information or place a purchase) with effectiveness (completeness and accuracy of the task), efficiency (time spent on the task), and satisfaction (user experience) within a system”;

- Out of the 20 identified design elements that impact user engagement, 7 key design elements (in order of importance) are navigation, graphical representation, organisation, content utility, purpose, simplicity and readability.” Garett et al. expand these design element definitions, but the key words are:

-

- Effective navigation: consistent menu/navigation bars, search features, multiple pathways and limited clicks/backtracking.

- Engaging graphical presentation: images, size and resolution, multimedia, font, font colour and size, logos, visual layout, colour schemes, and effective use of white space.

- Optimal organisation: logical, understandable, and hierarchical / architectural structure, arrangement / categorisation, and meaningful labels/headings/titles/keywords.

- Content utility: information is sufficient, of ongoing quality and relevant

- Clear purpose: 1) establishes a unique and visible brand/identity, 2) addresses visitors’ intended purpose and expectations for visiting the site, and 3) provides information about the organisation and/or services.

- Simplicity: clear subject headings, transparency, optimised size, uncluttered, consistent, easy, minimally redundant and understandable.

- Readability: easy, well-written, grammatically correct, understandable, brief, and appropriate.

References

Adner, R., & Kapoor, R. (2016). Right tech, wrong time. Harvard Business Review, 94(11), 60-67.

AlAwadhi, S. (2019). Marketing academic library information services using social media. Library Management, 40(3/4), 228-239. doi:10.1108/LM-12-2017-0132

Arteaga, S. (2012). Self-Directed and transforming outlier classroom teachers as global connectors in experiential learning. (Ph.D.), Walden University. http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.csu.edu.au/docview/1267825419/BD063751849440E5PQ/1?accountid=10344

Barnhart, B. (2020, January 5). The most important social media trends to know for 2020. [Blog post]. https://sproutsocial.com/insights/social-media-trends/

Business.gov.au (2019). Social media for business. https://www.business.gov.au/Marketing/Online-presence/Social-media-for-business

Garett, R., Chiu, J., Zhang, L., & Young, S. D. (2016). A literature review: website design and user engagement. Online journal of communication and media technologies, 6(3), 1.

Hicks, D., Cavanagh, M. F., & VanScoy, A. (2020). Social network analysis: A methodological approach for understanding public libraries and their communities. Library & Information Science Research, 42(3), 101029. doi: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2020.101029

Jenkins, H., Clinton, K., Purushotma, R., Robison, A. J., & Weigel, M. (2006). Confronting the challenges of participatory culture. https://www.macfound.org/media/article_pdfs/JENKINS_WHITE_PAPER.PDF

Kwon, K. H., Shao, C., & Nah, S. (2020). Localized social media and civic life: Motivations, trust, and civic participation in local community contexts. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 1-15.

Manca, S. (2020). Snapping, pinning, liking or texting: Investigating social media in higher education beyond Facebook. The Internet and Higher Education, 44, 100707. doi: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2019.100707

Mon, L. (2014). Social Media and Library Services. Morgan & Claypool Publishers. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/csuau/detail.action?docID=2010483.

Nisar, T. M., Prabhakar, G., & Strakova, L. (2019). Social media information benefits, knowledge management and smart organizations. Journal of Business Research, 94, 264-272. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.05.005

Schwerdtfeger, P. [Patrick Schwerdtfeger] (2013). What is web 2.0? What is social media? What comes next? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iStkxcK6_vY

Van Dijck, J. (2018). Introduction. In J. Van Dijck (Ed.), The Platform Society. Retrieved from Oxford Scolarship Online.

Describing and Analysing Educational Resources Module 1

I think a key to mention that ETL505 is different to ETL503 (Resourcing the curriculum) in that ETL503 is about providing quality resources but ETL505 is about “organising resources to facilitate effective access” (Hider, 2018, p.xv). Organising is the key word! So, now  I’m thinking, as per Hider (2018, p. 17), should the name of this class be changed to Information Organisation? (Just kidding). However, more seriously, by chapter 2 I was starting to get very annoyed by the amount of end of sentence prepositions used by Hider (e.g. ‘looking for’ should read simply as ‘looking’ or ‘for which they are looking.’ It is a minor detail I know, but compounded by at least 8 instances in chapter 2, I began to wonder about the quality of the editor).

I’m thinking, as per Hider (2018, p. 17), should the name of this class be changed to Information Organisation? (Just kidding). However, more seriously, by chapter 2 I was starting to get very annoyed by the amount of end of sentence prepositions used by Hider (e.g. ‘looking for’ should read simply as ‘looking’ or ‘for which they are looking.’ It is a minor detail I know, but compounded by at least 8 instances in chapter 2, I began to wonder about the quality of the editor).

What follows are my notes about the readings of Hider (2018) from the introductions and Chapters 1, 2 & 4:

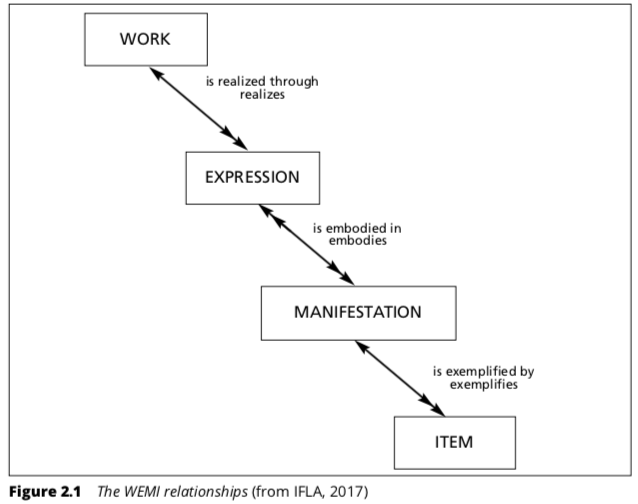

FRBR

Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records or (FRBR) is “a conceptual model of the ‘bibliographic universe’ involving 4 different ‘levels’ of information resource, originally set out in a report published by the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA)” in 1998 and revised in 2017 in IFLA’s Library Reference Model: a conceptual model for bibliographic information (Hider, 2018, p.25).

FRBR has 4 ‘entities,’ called: ‘works, expressions, manifestations and items,’ which are abbreviated ‘WEMI,’ which is shown by Hider in this Figure 2.1:

As well as in this circle chart by Lorenz (2012):

![Lorenz, A. (2012). [Screen shot]](https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/croe/files/2020/08/Screen-Shot-2020-08-05-at-4.25.35-pm.png)

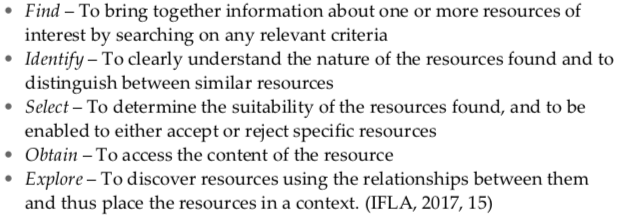

“The point is that different characteristics or attributes of items, manifestations, expressions and works are likely to be important when people think about them for the purposes of finding, identifying, selecting, obtaining and exploring them” (Hider, 2018, p.27).

It is a good point in Hider (2018, p.xiii) that, when trying to find, identify, select, obtain, (or access) resources (the FRBR), users can be lost, overwhelmed by choices and simply unable to choose. The resulting poor access to information, (see also my previous blog posts regarding filter failure and filter bubble) and being completely in the dark about quality information are problems that can all be solved by effective resource curation and description / access.

Interestingly, ‘bibliographic’ is defined as ‘book description.’ but as the definition of ‘book’ has widened, so too has the term ‘bibliographic’ (Hider, 2018, p.16). This is also important to note when using the term ‘bibliography.’

Information Resource Descriptions

Descriptions should different aspects of things that they are describing in either elements of: content, carrier, or both content and carrier (Hider, 2018, p.4). ‘Cataloguing’ or ‘indexing’ are often referred to as information, intellectual or knowledge organisation of resources (Hider, 2018, p.13). These are represented by their physical location, but also through their description and the comparison between various resources. In fact, the core of organisation lies in the relationships, commonalities and differences between resources (Hider, 2018, p.40).

The more resources a setting has, the more difficult it is to locate a resource based on its location, so an adequate and ‘representative’ (p.33) resource description (such as an catalogues, indexes, search engines, etc), and effective resource labels (a form of metadata) are key to locating the resource. Particularly, indexes are a vital tool for organising resources, as they are representations of the resources arranged in a user-friendly way (Hider, 2018, p.14-15).

NOTE: Search engines, linked data, data mining and granularity are considered ‘indexing content’ rather than ‘indexing of metadata’ and are part of a seperate field from information science called ‘information retrieval’ (Hider, 2018, p.18) because, in Hider’s view, search engines do not help with the formulation of search queries. However, the modern Web2.0 search engine(s) do have some artificial intelligence or ‘semantic web’ (Hider, 2018, p.19) capabilities, such as the ability to use individual online footprints to narrow (and possibly limit) search results.

“Information resource description is inevitably biased: it is influenced by the motives, situation, limitations and world-view of its creator” (Hider, 2018, p.23).

In terms of FRBR, and resource descriptions, and the resource seeking process that occurs inside the users’ heads, users may also check the ‘relevance criteria’ of the resource based on its content summary, provenance, quality, currency/date, quantity of text, or format and the ‘relevance rankings’ of information retrieval systems, such as those used by the semantic web 2.0, which play a large part in the selection of resources by users (Hider, 2018, p.35-38).

Metadata

Metadata, according to Hider (2018) is an “information ecology” (p.12) “providing an overview of both the process and the product” of organising resources (p.xv) and “information resource description” (p.4) including both the “carrier” (format) and the “content” (information) of the resource (p.5). I interpret that to mean that metadata is an overview of how a resource was created, is delivered and information describing its content.

There are 4 areas of importance with metadata: elements, values, format and transmission (Hider, 2018, p.6-10).

1. Elements or data ‘fields,’ provide the structure of the metadata and are infinite, however it is important to narrow them down to what will be of value to the user, e.g. a resource’s title. The elements are the ‘building blocks’ of metadata and each element describes an ‘attribute’ of the resource, such as its identifier/number, name/title, creator/author/corporation, subject, etc. (Hider, 2018, p.23, 30, 32, 33).

NOTE: Systematic (numerical) identifiers are most commonly known as ISBN’s (international standard book numbers), ISSN (international standard serial numbers), ISMN (international standard music numbers) and DOI’s (digital object identifiers), and the lesser known ISTC (international standard text code), and ISAN (international standard audiovisual number) to name a few (Hider, 2018, p.34).

2. Values, or fundamental content of the metadata are also infinite but often have the greatest impact on the quality of the metadata and are key to a user utilising the description in order to locate a resource (Hider, 2018, p.28). (See more information in Hider, 2018 chapter 5).

3. The method by which the values are encoded or recorded is known as the format, which needs to be compatible with the information retrieval system being used by a setting (note below); and

4. The transmission of the metadata is the protocol used to input the metadata into the information retrieval system, so that the metadata is accessible to the users.

This image found in Hider (2018, p. 7) helps explain the 4 areas of metadata:

There are also the 6 purposes of metadata provided by Hayes’ ‘6 point model’ (in Hider, 2018, p.5): 1. resource identifying and describing, 2. information retrieving, 3. information resource managing, 4. intellectual property right managing, 5. e-commerce/e-government support, and 6. information governing. If we take into account that there are 3 types of metadata: administrative, structural and accessible information resource descriptions, accessible descriptions link to 1. and 2. in Hayes’ model (in Hider, 2018, p.5) and these best correlate with finding, identifying, selecting, obtaining and exploring resources.

Finally, metadata must be continually evaluated for quality control and ongoing growth purposes. We must ask ourselves: 1. Is the metadata from an external source in the right format for our information retrieval system? 2. Does it need improving or editing based on our context (users, systems, costs, or search contexts)? 3. Will it withstand constant technology advances? 4. Is it standardised enough that it might be shared in a (global) network? (Hider, 2018, p10-11). 5. Who are our users, both end-users and intermediary and what are their information needs, knowledge and behaviours? 6. What metadata should be selected to help users to access the information they are seeking? (Hider, 2018, p.24). 7. What methods are we using to analyse our users’ search queries? (Hider, 2018, p.33).

This concept of metadata is interesting to me as a teacher as I have read recently that making students aware of the complex process of writing is key to their success as writers – rather than the actual content of the writing (including punctuation, grammar, spelling or handwriting) itself. Cataloguing / describing resources effectively is not only a means for users to access the resource but also to understand the resource itself at a deeper level. [In fact, one could say that the metadata itself is an information resource!]

This concept of metadata is interesting to me as a teacher as I have read recently that making students aware of the complex process of writing is key to their success as writers – rather than the actual content of the writing (including punctuation, grammar, spelling or handwriting) itself. Cataloguing / describing resources effectively is not only a means for users to access the resource but also to understand the resource itself at a deeper level. [In fact, one could say that the metadata itself is an information resource!]

Information Retrieval Systems / SCIS / Oliver / RDA

Information retrieval systems are designed to improve access to collections of information resources and may influence the nature and structure of the metadata (Hider, 2018, p.6).

Information retrieval systems are a means of ‘cataloguing,’ providing ‘bibliographic data,’ ‘indexing,’ ‘tagging,’ ‘archival description,’ and in some cases, ‘museum documentation’ (Hider, 2018, p.6).

Commonly used in Australia are the cataloguing information retrieval systems: SCIS and Oliver, and here is an image showing how SCIS use various standards in the process of creating their cataloging metadata:

However, our first assessment in ‘Describing and Analysing Educational Resources’ requires us to use the library cataloguing code: Resource Description and Access (RDA) mentioned by Hider (2018, p.xv).

Who is responsible?

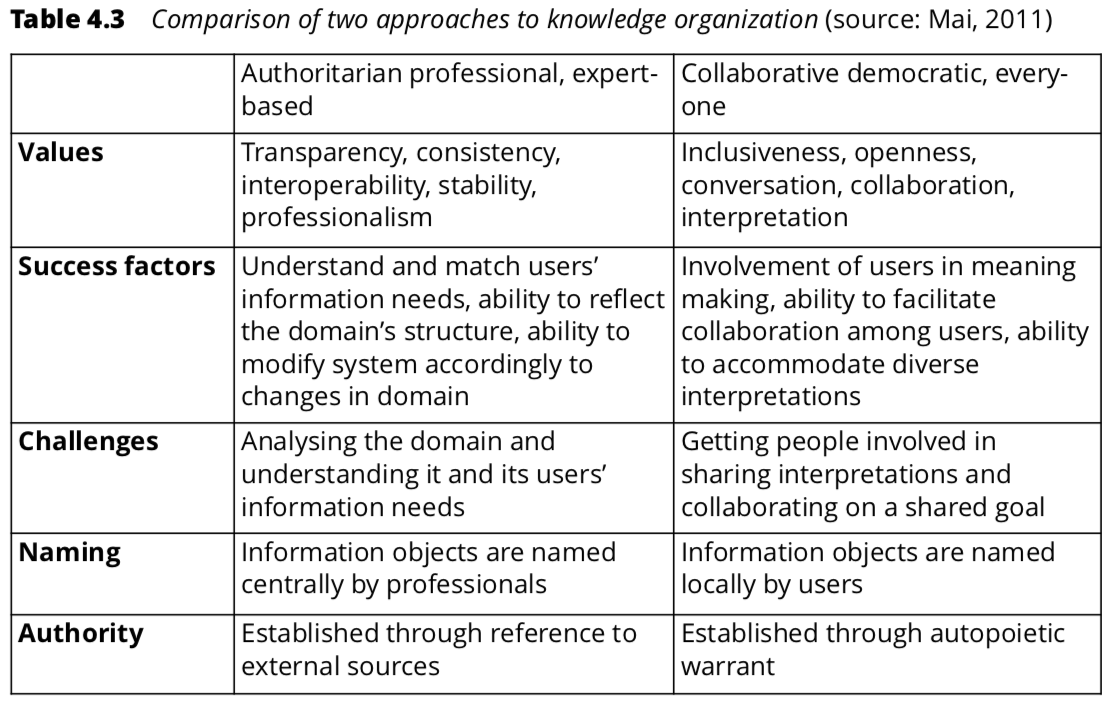

Publishers, authors, creators, information retrieval system operators, teacher librarians/information specialists/metadata librarians, archivists, records managers, museum curators, information architects and the general public ‘end users’ can all be responsible (however uncontrolled, inaccurate, informal and inconsistent) for creating and disseminating metadata through the use of publishing standards, the requirement for authors to write abstracts and keywords for their resources, as well as through desktop publishing computers, social media applications and the internet which have made it far easier for end users to create (tag, meta-tag, label, #tag, hyperlink or embed) and disseminate metadata and information resources (Hider, 2018, p.74-86). The relative benefits of formal vs informal knowledge organisation is best represented by this Table 4.3 by Hider (2018, p. 87):

Information specialists / teacher librarians need to establish ‘communities of practice’ (Hider, 2018, p.77; See also my previous blog posts on this topic). They must be able to understand the foundations of metadata in order to fulfil the roles and responsibilities of directing and guiding students / users towards quality information resources and to best be able to access the resource though effective cataloging and to access the content within the resource through effective information literacy skills (Hider, 2018, p.75-77; See also my other posts on TL roles and responsibilities).

Note: Computers/semantic web/applications can also do indexing and metadata of sorts, and this is improving rapidly, however computer programs still require human input and regulation in order to present metadata effectively (Hider, 2018, p.88-89).

Genrefication – Do fiction books inform?

I like it that Hider (2018, p.1-2) points out that, although they will always have a primary purpose, resources can have different purposes. I have been sorting my personal library after our house move and found it challenging whether to put self-help style fiction children’s books in the fiction picture book section or in the teaching key learning area (KLA) ‘genre’ section of my library. For example, the picture book ‘I like myself’ is used in stage 1 PDHPE (health) lessons. Do I put it in that genre or do I keep it with straight fiction picture books, organised by author nam e? I chose genre–after all, it isn’t by a well known author and I need to be able to access it quickly. It’s primary purpose is to inform, rather than entertain, yet I fully support the argument that a good number of children’s fictional picture books have the primary purpose of informing their readers. (Genrefication…see the link for an idea for further reading).

e? I chose genre–after all, it isn’t by a well known author and I need to be able to access it quickly. It’s primary purpose is to inform, rather than entertain, yet I fully support the argument that a good number of children’s fictional picture books have the primary purpose of informing their readers. (Genrefication…see the link for an idea for further reading).

References

Chadwick, B. (September 2017). SCIS: Bibliographic data for education. [Interact2 Recorded Adobe Connect Webinar; Screen shot of protocols]. Education Services Australia.

Hider, P. (2018). Information resource description: Creating and managing metadata (2nd ed.). London: Facet. [Introduction(s) & Chapters 1, 2, 4]

Lorenz, A. [Andrea Lorenz]. (2012, August 9). FRBR simplified. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LPBpP0wbWTg

Further reading

Chadwick, B (2015). SCIS is more. Connections, 2015(92), 12. https://www.scisdata.com/connections/issue-92/scis-is-more/

Schools Catalogue Information Service (2020). Schools Catalogue Information Service. https://www.scisdata.com

Schools Catalogue Information Service (2020). SCIS catalogue. https://myscisdata.com/discover (accessible once you have logged in to SCISData)

Schools Catalogue Information Service (2019). SCIS standards for cataloguing and data entry. https://www.scisdata.com/media/1738/scis-standards-for-cataloguing-and-data-entry.pdf

Schools Catalogue Information Service (2020). SCIS subject headings. https://my.scisdata.com/standards (accessible once you have logged in to SCISData)

“This budget is too tight, could I try the next size up?”

(Reflection on ETL503 Module 3.1 Funding the Collection):

- “Should teacher librarians have the responsibility of submitting a budget proposal to fund the library collection to the school’s senior management and/or the school community? Or should such proposals come from a wider group such as a school library committee?

- Is it preferable that the funding for the school library collection be distributed to teachers and departments so they have the power to determine what will be added to the library collection?” (Giovenco 2019).

Well, here we go again. I thought when I got out of marketing (where I was given a budget amount and had to account for all expenditures within that budget) that I had seen the last of tight budgets. Tsk Tsk. Welcome to the world of being a Teacher Librarian!

- The responsibility for budgeting for the library is possibly best done collaboratively with the teacher librarian and the school executive and possibly the school’s P&C (who also have access to funds). As per the CSU Module (Giovenco 2019) a TL should be a budget collaborator, steward and thinker. Moreover, having never been in charge of creating a budget, I would be hesitant to take on a budget on my own and would be reliant on someone with expertise to help me.

- I have not mentioned classroom teachers intentionally. Should we collaborate with teachers about resources they might need? Yes of course. Should teachers have a say in the budget? Perhaps, yet I am leaning towards no. After all, why would teachers have a say in the budget for the library when they don’t have a say in any way what-so-ever in any other area of the budget? Teachers in some schools are given ‘classroom budgets’ and I think that spending that money is enough for them to worry about. Just do a Google search for ‘What should I spend my classroom budget on?’ and you will get 55,600,000 results. As soon as you ask for input, the assumption will be that what is asked for will be received and that is dangerous ground. Better to survey the teachers and ask what sort of resources they were thinking of or if they had any ideas and leave the budgeting to an executive committee that includes the TL.

In order to have a balanced (or at least one that fits) budget and a fully resourced curriculum I believe it is important to start with a clear policy in the Collection Development Plan.

There are loads of resources on how to do this (Such as Lamb & Johnson 2012, & Australian Library and Information Association (ALIA) Schools et al 2017, pp.20-25) and I intend to make good use of them!

Good Idea: Let’s make sure that a ‘perfect fit’ or balanced budget remains the goal as opposed to being in surplus…we don’t want to behave like or be perceived as politicians do we? Well, speaking for myself, I certainly do not.

Good Idea: Let’s make sure that a ‘perfect fit’ or balanced budget remains the goal as opposed to being in surplus…we don’t want to behave like or be perceived as politicians do we? Well, speaking for myself, I certainly do not.

To show the ‘balance’ (or presumably the lack thereof) I most certainly agree to having a section for the library in the School Annual Report in the format suggested by the school or using a template such as the one below:

References

ALIA Schools & Victorian Catholic Teacher Librarians. (2017). Budgeting policies and procedures. In A manual for developing policies and procedures in Australian school library resource centres. Retrieved from https://www.alia.org.au/groups/alia-schools

Giovenco, G. (2019). Budgeting for a balanced collection. In ETL503: Module 3: Accession and Acquisition [Subject module]. Retrieved from Charles Sturt University website: https://interact2.csu.edu.au/webapps/blackboard/content/listContent.jsp?course_id=_42383_1&content_id=_2636378_1

Lamb, A. & Johnson, H.L. (2012). Program administration: Budget management. The School Library Media Specialist. Retrieved from http://eduscapes.com/sms/administration/budget.html

Why ‘Teach Starter’ Makes Me Cringe

[Reflection on ETL503 Module 2.2 The Balanced Collection]

Okay, I get it. I’m a fish out of water in my current local government area (LGA) of schools. As a (recent) day to day casual relief teacher, I am increasingly finding myself filling in for ‘New Scheme’ temps who are fresh from University. As a seasoned educator who has worked in upwards of 15 schools, over 12 years, in a variety of full time, part time, contract and casual positions, I should be be helping teachers who are starting out in the profession.

When I first started teaching, the more seasoned educators helped me too. They guided me on how to teach grammar when my generation was left behind in an era where grammar wasn’t explicitly taught. They gave me behaviour management ideas and resources for successfully delivering guided reading literacy groups. They came in to my class and taught lessons while I observed. They suggested training courses and organised my attendance. They gave me formats for planning and in some team situations, whole units of work complete with required resources already printed and ready to go. They did these things because they wanted me to succeed in the goal we all shared: improved student outcomes.

Now, in my current LGA context where the number of temporary teaching positions outweigh the number of permanent or seasoned teachers, sharing isn’t done willingly. Competition for positions is the number one game. As a casual (this year) I am happy to not be an active part of that. However, it still has an impact on me when I want to help but I’m seen as either a ‘substandard’ teacher filling in for more capable teachers or competition for contracts for next year. Or maybe people just don’t want to share because they are afraid of what I might say…

I say all of this because I am struggling to understand why the hell everyone here is so obsessed with using Teach Starter (2019) (https://www.teachstarter.com/) to program for their classes?

Teach Starter (2019), in my view is for that little gap in the unit of work where the resource is outdated or unavailable, for finding more diverse resources to differentiate a program, or perhaps for people who don’t know how to program or create or collaborate to create units of work or resources. It is for schools who don’t already have scope and sequence documents. In 2019, what schools don’t have programs, units of work or scope and sequence documents? I am utterly horrified.

And heaven help me if I, a mere casual, ask to see someone’s teaching and learning program. You’d think I’d asked to see the inside of their bedside table. Seriously, if you can’t stand behind your program proudly you need to lift your game.

Another issue that I have with Teach Starter (2019) is that it costs money to be a member and access the (very basic and ‘cutesy’) resources that any teacher worth their salt could whip up in five minutes.

Fine if the school have purchased it for the teachers to use based on collaboration and discussion with all stakeholders and the program fulfils a context need. Not fine if the teachers have to pay for access themselves. Not fine for casuals (like myself) who are left a sentence or two as a teaching and learning program for the day: e.g. “go into Teach Starter and teach the powerpoint on ‘communication-then and now.'” Oh my god, please kill me now.

Furthermore, just because the resources are digital, doesn’t mean the delivery isn’t the same as ‘chalk and talk.’ (For a resource to truly be a useful digital learning tool, it needs to offer more than just a digital version of a chalkboard!)

So let’s program effectively hey? Let’s start with the point of need for our individual students based on suggested syllabus outcomes, meet as a team to discuss a scope and sequence, share ideas and resources for the lessons and make sure those lessons meet the Quality Teaching Framework standards (Collins, 2017). Let’s ensure that the lessons can then be delivered effectively no matter what teacher turns up on the day, by making our programs easily accessible and truly collaborative.

If Teach Starter (2019) is a part of that, then so be it. So long as we keep in mind that programs full of resources and websites or applications full of resources shouldn’t be the only avenue that we use for programming.

In the meantime, I think we, Teachers and Teacher Librarians et al, need to get out of Teach Starter (2019) and stop starting at resources, and instead we need to start at the point of need for our students. Perhaps the only way for look for this to occur is to first get improved executive leadership skills in our LGA…or maybe fewer ‘New Schemers’…Now there’s an idea.

References

Collins, L. 2017, ‘Quality Teaching in Our Schools’, Scan, 36(4), pp. 29-33. Retrieved from: https://education.nsw.gov.au/teaching-and-learning/professional-learning/scan/past-issues/vol-36,-2017/quality-teaching-in-our-schools

Teach Starter (2019). Teach Starter Pty Ltd. Retrieved from: https://www.teachstarter.com/

Beautiful Doesn’t Mean New

(Reflection on ETL503 Resourcing the Curriculum Module 2)

When ‘resourcing the curriculum,’ as a teacher librarian I will need to remember lots of information as mentioned in the module. I will also need to remember two things:

- Beautiful doesn’t always mean new, (see image) and

- Sometimes patron/student needs outweigh their wants. (*See below)

1. New things aren’t always the best things. My grandmother’s recipe for chicken and dumplings far outweighs any new dishes that my mother or my aunts dreamt up for our yearly Thanksgiving or Christmas feasts. Old buildings using engineers, fine brickwork, stone masonry or intricate carpentry far outweigh cardboard or plastic construction-particularly in times of natural disasters like earthquakes.

Should digital resources replace physical resources? If new is perceived as better, then will Artificial Intelligence replace teachers? Guilherme (2019) goes into this with a powerful depth. We are facilitators, but we are also teachers. We are providers of information but we also teach the skills to interpret the information and utilise it in life.

2. A key factor in ‘resourcing the curriculum’ is that it reinforces the concept of ‘information as a commodity.’ As much as we’d like libraries and information to be free, the fact is that neither are without cost. (Whether that cost is paid by taxes or individuals is a political debate for another day.)

In terms of ‘information as a commodity,’ this has some powerful landmines. The idea that information can have ownership has led to a strong community of hackers whose primary function is to provide information that someone or a corporation has deemed ‘a commodity’ and opportunity for profit.

For librarians, ‘information as a commodity’ is also full of landmines. We are adults, we are educated, we have a job to facilitate the education of students. We are also, gendered, cultural, geographical, and loaded with our own personal string of internal bias.

*Does the student voice of their needs or wants, outweigh what society (and the teacher librarian) view as student needs or wants or vice versa?

I am having a lot of colliding thoughts about ‘engaging learners’ and fulfilling ‘needs’ of the learners &/or the school community and ‘who has the final say’ in resourcing the curriculum.

I say colliding because I have taught at so many different schools (South West Sydney, Far West, casually and through temporary engagement, RFF, classroom teaching, job share, etc) and can see a common lack of consideration for sociocultural context of students for programming and planning. If programming and planning were a building, the foundation is the sociocultural context. Without a sound knowledge of the school’s foundation, the building / educational program will crumble and resourcing the curriculum becomes moot. The library starts to fail or becomes irrelevant. The funding decreases. The principal sees no point in allocating a qualified TL. People start throwing around the idea of getting rid of a library altogether. In the distance: sirens.

Yesterday I worked at a geographically isolated and drought affected primary school with a large number of students from very low SES, high evidence of trauma (large ATSI population, witnesses of or suffers of domestic violence, neglect, alcohol / drug / physical / mental / emotional abuse / deaths in the family), higher than state average numbers of students with diagnosed and undiagnosed disabilities (including lead affected disabilities due to historical mining practises) and the students in this area are, overall, not meeting state expectations based on NAPLAN results. In my area, there are a statistically higher numbers of these things in all of the schools but in this particular school, the statistics are more visible.

As a result, most of the students are coming to school to feel or express love. (See Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs as explained by McCloud, 2018 in the reference list below). They have some basic human needs that are not being met at home and they come to school to have these needs met.

However, the main push from the teacher of the class I was on yesterday, was to teach content that was not adjusted to meet the needs of the students as individuals. It was straight from the stage based syllabus and so difficult that the students were not just disengaged but were actively protesting and having meltdowns before my eyes. When I suggested deviating from the plan, everyone agreed and calm was restored.

Too often in today’s educational realm, the needs of students are filled with a top-down mentality. Schools start at what the administration identify as a need-based on Australian or state benchmarks and societal goals (eg. NAPLAN, national curriculum or state syllabus documents). They then look to the local administrators to identify needs, such as recent literacy or numeracy training or strategies (eg. L3 or TEN). Then the teachers weigh in (eg. Sport or Creative art or Social-Emotional-Learning – which may or may not be sourced from evidence based practises). Parents and families sometimes get to have a say – and it is interesting to note the capability of the families to engage with the form of communication method chosen by the school as often low SES families cannot get to meetings and cannot access digital forms of communication or are too illiterate themselves to fill in a form – (eg. ‘I want my child to learn how to do public speaking so they can become a prefect or school captain’). Then, almost as an addendum, a little box is put out in the library to gather the student’s identified needs or wants (a system designed to preference students with high enough literacy skills and levels of engagement already to participate).

I prefer to value the student’s needs first – identified by them, identified through a authentic TL relationship with the students, and identified by a thorough a collaborative study of the socio-cultural context (Farmer, et al 2018) of the school. The library and classrooms in the example of the school where I worked yesterday, need to focus on being places for students to have voice and to feel loved and express love. The school needs to be a safe shelter and offer warmth and basic physical comfort. It needs to have a teacher librarian who is acutely aware of the ‘kinder culture’ (Steinberg, 2018) of students in the school and resources the library to embrace the ‘kinder culture’-which is the main key to engagement, particularly with students from low SES, high disability or who’ve been traumatised.

Once these areas have become the main priority for resourcing the curriculum and are working well, and the students are engaged, then the questions can be asked of parents and carers and the community of what they identify as ‘needs.’ Teachers can also weigh in, followed by the local teaching community and administrations. Finally, a little box can be put out for the state and federal needs so that they can have their say.

References:

Farmer, S., Dockett, S., & Arthur, L. (2014). Programming and planning in early childhood settings. Chapter 6. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com

Guilherme, A. AI and education: the importance of teacher and student relations. AI & Soc. (2019) 34: 47. Retrieved from: https://doi-org.ezproxy.csu.edu.au/10.1007/s00146-017-0693-8

McCloud, S. (2018). Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Retrieved from: https://www.simplypsychology.org/maslow.html

Steinberg, R.S. (2018). Kinderculture : The corporate construction of childhood. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com

Resource Selection Decision Making Model

(This reflection follows my readings within ETL503 Module 2)

While resource selection for teacher librarians is complex, I think it is important to vet resources based on agreed quality teaching practises across the whole teaching community and not just library collections.

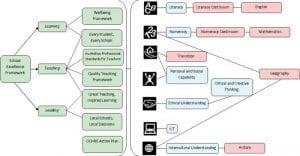

Appropriate resource selection is something that will assist with ‘external validation’ from NESA, school plan formation and the NSW Department of Education ‘School Excellence Framework’ (2014) (found in NSW Department of Education (2019) Teaching and Learning).

For this reason and with suggestions from Hughes-Hassell & Mancall (2005) and the NSW Department of Education (2019), I have created a (Draft) GoogleForms questionnaire, that offers an array of resource selection decision making criteria. The questionnaire has been designed for any stakeholder to be able to answer the questions, however they may need librarian guidance for some questions such as context and philosophy. To have a look at my draft selection questionnaire, click here.

However, as noted by Hughes-Hassell & Mancall (2005) we must know the context of the school and teaching and learning philosophies of stakeholders prior to validating a resource.

While at UWS in 2006, I created a survey for families to help me identify each student’s context. For schools, this should be something created collaboratively and using information from my UWS studies, I have also created a (Draft) GoogleForms questionnaire to help schools identify their context. To have a look at my draft context questionnaire, click here.

I want to improve the context survey by reviewing a key text from my Bachelor

Another example of guidance might be in identifying teaching and learning philosophies. While at UWS in 2006, I realised this was an area of weakness in the degree and in teachers in general and I created a template for thinking about the various aspects of teaching and learning in order to arrive at a coherent and well-thought out philosophy, based on Posner’s (1996 & 2005) Field Experience: Methods of reflective teaching. To have a look at my draft philosophy questionnaire, click here.

References:

Hughes-Hassell, S. & Mancall, J. (2005). Collection management for youth: responding to the needs of learners [ALA Editions version]. Retrieved from http://ebookcentral.proquest.com.ezproxy.csu.edu.au/lib/csuau/detail.action?docID=289075

Posner, G. J. (1996). Field Experience: Methods of reflective teaching (4th ed.). New York: Longman. (p. 131-134);

Posner, G. J. (2005). Field Experience: a guide to reflective teaching. 6th ed. Boston: Pearson Education Inc.

Prumm, K. & Patruno, R. (2016) Elements of Learning and Achievement Manual – NSW Department of Education. Retrieved from: https://theelements.schools.nsw.gov.au/introduction-to-the-elements.html

NSW Department of Education (2019) Teaching and Learning. Retrieved from: https://education.nsw.gov.au/teaching-and-learning]