OLJ Task 2: The influence of technology on society or OLJ Task 3: Reflections on the impact of change

To be or not to be (active on social media) is no longer the question

If we want ‘customer-driven, socially rich, and collaborative model of service and content delivery’ (module 2) then we must stop asking ‘why’ or ‘when’ and start asking ‘how.’

If we want ‘customer-driven, socially rich, and collaborative model of service and content delivery’ (module 2) then we must stop asking ‘why’ or ‘when’ and start asking ‘how.’

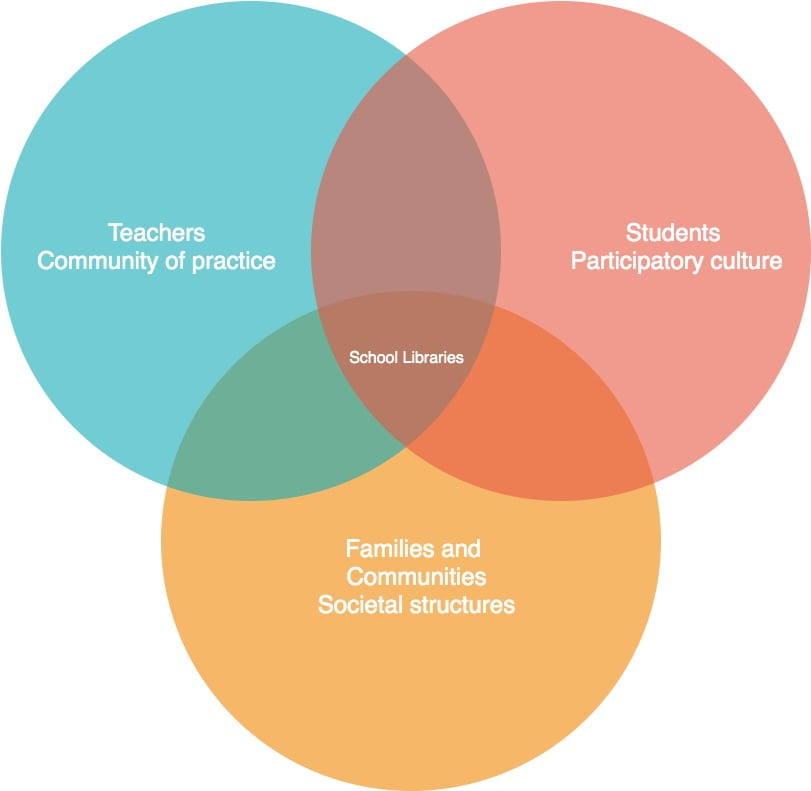

Why do we expect teachers to have a work culture aiming for a ‘community of practice’ (which I’ve discussed at length in previous blog posts, but also mentioned by Nisar, Prabhakar, G & Strakova, 2019), however, conversely, we expect students work almost entirely independently? Today’s working society has shifted, and so too has kid culture. Just as work places are becoming communities of practice, 21st century students have a participatory culture (also discussed in previous blog posts).

Jenkins, Clinton, Purushotma, Robison & Weigel (2006, p.3) define a participatory culture as: “a culture with relatively low barriers to artistic expression and civic engagement, strong support for creating and sharing one’s creations, and some type of informal mentorship whereby what is known by the most experienced is passed along to novice. A participatory culture is also one in which members believe their contributions matter and feel some degree of social connection with one another (at least they care what other people thing about what they have created).”

According to Jenkins (et al., 2006), forms of participatory culture could include affiliations, expressions, collaborative problem-solving and circulations [“Affiliations – memberships, formal and informal, in online communities centred around various forms of media, such as Friendster, Facebook, message boards, meta-gaming , came clans or MySpace); Expressions – producing new creative forms, such as digital sampling, skinning and modding, fan video-making, fan fiction writing, zines, mash-ups); Collaborative Problem-solving – working together in teams, formal and informal, to complete tasks and develop new knowledge (such as through Wikipedia, alternative reality gamine, spoiling); or Circulations – shaping the flow of media (such as podcasting, blogging).”]

Artega (2012, p.72) writes, “social media extends the social milieu to the digital sphere where opportunities for global social participatory learning are plentiful.” Thus, to be viable in today’s globally connected society, particularly in western civilisation where a participatory culture has become the ‘norm,’ an educational facility’s social media presence is not only something that is necessary, but is something that must be done effectively.

“For library managers, questions are moving beyond how to initiate and launch social media to the more challenging problem of how to do social media well— how to better integrate social media into the life of the library, how to more fully engage the library’s staff and users in social media; how to make the library’s social media more effective in outreach and delivery of services, and how to measure the library’s presence and activities within social media in ways that truly matter. The next wave of trends in social media use are also always looming on the horizon— what will be the next big social site where users will be going next within the social media landscape, and should the library follow?” (Mon, 2014, p.51).

Some purposes for social media have been suggested by Mon (2014, p.24) as supported by the research of AlAwadhi (2019) to include: increased avenues for feedback from users, promotion and advocacy of the school &/or library, improved information access through outreach programs, deliverable educational or support hubs, improved collections and stronger or more frequent global collaborations. Notably, Kwon’s (2020) research places building trust ahead of information motivation as a reason for use of community social media platforms.

Roadblocks to consider

There is also the issue of needing to be innovative in the types of platforms that we promote as educators (as supported by the research of Manca (2020). Which brings up another roadblock to implementing social media for schools is the fact that there is an age limit for access – most students in K-6 Australian educational settings are below the age of 13 and cannot be encouraged by educators to look at nor participate in most social media applications. This means we have to tailor our content to an older demographic and seek out other (less public) social media platforms for younger students.

Some additional roadblocks or things to consider have been provided by Business.gov.au (2019) and they are to have a clear social media strategy, be mindful that additional staff or resources may be required for daily monitoring of all online platforms, be prepared for inappropriate behaviour (bullying, harassment, negative feedback, misleading or false claims, copyright infringement, information leaks or hacking) and have an action plan ready within your policy documents detailing specifically how to deal with these instances prior to launch date(s).

Hicks, Cavanagh & VanScoy (2020) recommend monitoring a library’s online presence via a ‘social network analysis (SNA).’ The SNA is a ‘theoretical framework and quantitatively oriented methodology’ for libraries to understand their ‘big data stories’ or connections with their community identifying relevant patterns and relationships among individuals, groups, or organisations over a specified period of time.

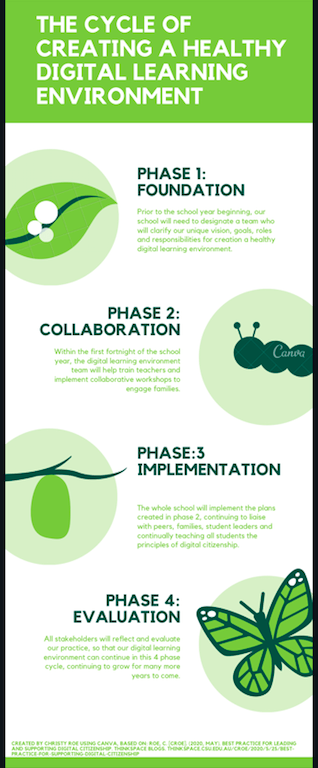

All of these issues need to be incorporated into the digital learning environment creation plan, a four phase process that I’ve detailed in a previous blog post from Digital Citizenship, but that can best be summarised in this infographic:

How to design a platform and design it well, improving engagement (web 2.0)

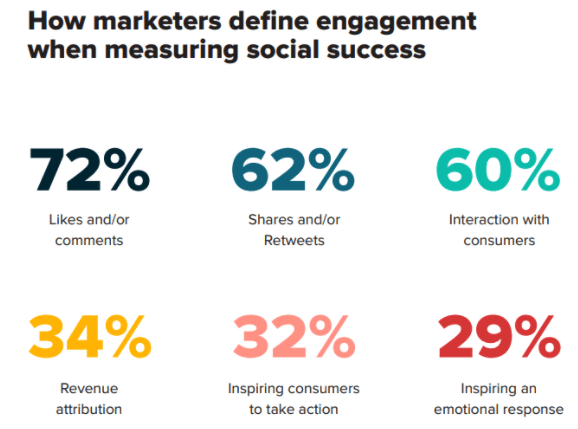

This leads to the next issue – how to have a website (web 1.0), that is interactive (web 2.0) and makes the step towards linking the online world to the offline world (web 3.0). We need to be thinking beyond web 1.0 in terms of having a simple ‘face’ website that offers little to no interaction and does not enable, encourage (nor monitor) engagement but a platform, website and social media presence that actively engages our users. The web 2.0 model of ‘likes’ is also becoming an outdated model and with web 3.0 we must begin to think of our digital presence as fully interactive, including building meaningful ongoing connections (Barnhart, 2020).

But each context must first ask “what does it mean to have ‘engaged users?” and “what platforms / website / social media should we use to engage them?”

After my practical work-placement in a local public library, where I completed two weeks of ‘virtual’ research on website design (offering several recommendations for website development for the library), I realise that there are almost infinite resources, research and opinions on how to design effective websites. I don’t believe that my understanding of moving from the web presence currently (as web 1.0) to web 2.0 (more interactivity) to even web 3.0 (content creation by the users) was fully developed, until I watched the video provided in module 2 of INF506 (Schwerdtfeger, 2013). I wish I had been able to communicate this idea previously.

Yet, one key article that I did find, in the interest of brevity, was Garett, Chiu, Zhang & Young’s (2016, p.1) literature review on website design in terms of user engagement. Their 4 notable findings were:

- “Websites have become the most important connection to the public and using social media links on websites may increase user engagement;

- Proper website design is critical for user engagement, because poorly designed websites result in a higher user ‘bounce’ rate (users do not proceed past the home page) whereas, well designed websites encourage user exploration and revisit rates;

- The International Standardised Organisation (ISO) (in Garett, et al., 2016, p.1) defines website ‘usability’ as: “the extent to which users can achieve desired tasks (e.g., access desired information or place a purchase) with effectiveness (completeness and accuracy of the task), efficiency (time spent on the task), and satisfaction (user experience) within a system”;

- Out of the 20 identified design elements that impact user engagement, 7 key design elements (in order of importance) are navigation, graphical representation, organisation, content utility, purpose, simplicity and readability.” Garett et al. expand these design element definitions, but the key words are:

-

- Effective navigation: consistent menu/navigation bars, search features, multiple pathways and limited clicks/backtracking.

- Engaging graphical presentation: images, size and resolution, multimedia, font, font colour and size, logos, visual layout, colour schemes, and effective use of white space.

- Optimal organisation: logical, understandable, and hierarchical / architectural structure, arrangement / categorisation, and meaningful labels/headings/titles/keywords.

- Content utility: information is sufficient, of ongoing quality and relevant

- Clear purpose: 1) establishes a unique and visible brand/identity, 2) addresses visitors’ intended purpose and expectations for visiting the site, and 3) provides information about the organisation and/or services.

- Simplicity: clear subject headings, transparency, optimised size, uncluttered, consistent, easy, minimally redundant and understandable.

- Readability: easy, well-written, grammatically correct, understandable, brief, and appropriate.

References

Adner, R., & Kapoor, R. (2016). Right tech, wrong time. Harvard Business Review, 94(11), 60-67.

AlAwadhi, S. (2019). Marketing academic library information services using social media. Library Management, 40(3/4), 228-239. doi:10.1108/LM-12-2017-0132

Arteaga, S. (2012). Self-Directed and transforming outlier classroom teachers as global connectors in experiential learning. (Ph.D.), Walden University. http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.csu.edu.au/docview/1267825419/BD063751849440E5PQ/1?accountid=10344

Barnhart, B. (2020, January 5). The most important social media trends to know for 2020. [Blog post]. https://sproutsocial.com/insights/social-media-trends/

Business.gov.au (2019). Social media for business. https://www.business.gov.au/Marketing/Online-presence/Social-media-for-business

Garett, R., Chiu, J., Zhang, L., & Young, S. D. (2016). A literature review: website design and user engagement. Online journal of communication and media technologies, 6(3), 1.

Hicks, D., Cavanagh, M. F., & VanScoy, A. (2020). Social network analysis: A methodological approach for understanding public libraries and their communities. Library & Information Science Research, 42(3), 101029. doi: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2020.101029

Jenkins, H., Clinton, K., Purushotma, R., Robison, A. J., & Weigel, M. (2006). Confronting the challenges of participatory culture. https://www.macfound.org/media/article_pdfs/JENKINS_WHITE_PAPER.PDF

Kwon, K. H., Shao, C., & Nah, S. (2020). Localized social media and civic life: Motivations, trust, and civic participation in local community contexts. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 1-15.

Manca, S. (2020). Snapping, pinning, liking or texting: Investigating social media in higher education beyond Facebook. The Internet and Higher Education, 44, 100707. doi: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2019.100707

Mon, L. (2014). Social Media and Library Services. Morgan & Claypool Publishers. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/csuau/detail.action?docID=2010483.

Nisar, T. M., Prabhakar, G., & Strakova, L. (2019). Social media information benefits, knowledge management and smart organizations. Journal of Business Research, 94, 264-272. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.05.005

Schwerdtfeger, P. [Patrick Schwerdtfeger] (2013). What is web 2.0? What is social media? What comes next? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iStkxcK6_vY

Van Dijck, J. (2018). Introduction. In J. Van Dijck (Ed.), The Platform Society. Retrieved from Oxford Scolarship Online.