A recurring theme throughout my study during ETL401, has been the importance of evidence based practice (Galimi, 2020, May 4) as an ongoing part of the role (Galimi, 2020, March 11) of a teacher librarian (TL). My thinking has evolved during this short space of time, to find ways to promote teacher librarianship (Galimi, 2020, May 25) and to ensure my practice (Galimi, 2020, May 4) includes numerous measures to provide cumulative evidence for practice, evidence in practice, and evidence of practice (Todd, 2009, p.89).

I strongly resonate with the claim from Kuhlthau et al (2012) that teachers working in “isolated silos” does not lead to effective teaching and learning (p. 16). This also applies to IL, “collaboration at the highest level between teachers and TLS remains the critical factor in the successful integration of IL into the curriculum” (Garrison & FitzGerald, 2019, p. 3). The impacts of communication technologies has changed our notion of literacy to multiliteracies due to multimodal meanings (Galimi, 2020, May 21). Kalantzis raised the important question of “how do we teach students to extract meaning from these increasingly complicated and diverse literacies?” (Kalantzis et al, 2002, p.2). I was surprised by the list of literacies in the learning module, I was unaware of metaliteracy, transformational literacies and workplace literacy which of course makes sense given the information landscape we are all part of.

Mardis (2016) suggests technology can build trust through collaboration within the school community using curriculum mapping tools, curation tools and digital note taking applications (p. 76). Approaching teachers as a resource, saving them time and providing expertise in technology would go a long way in fostering collaboration within the school community (Galimi, 2020, April 30). Guided inquiry would be a perfect example of the use of these tools in a collaborative environment.

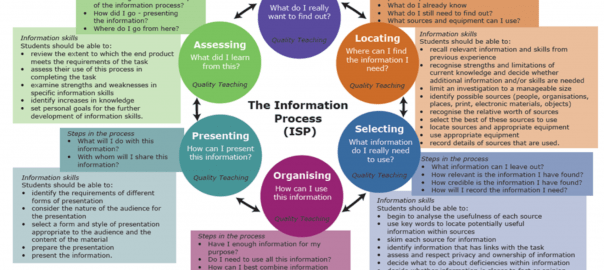

From all of the information literacy models (ILMS) studied, Guided Inquiry (GI) (Kuhlthau et al, 2012) gave me an instant ‘wow’ moment. I connected with GI (Galimi, 2020, May 3) on a personal level (Galimi, 2020, May 9), finding the inquiry tools useful (Galimi, 2020, May 8) to put in practice for my own research in this course and having just experienced the emotions (Galimi, 2020, May 25) described in the Information Search Process (ISP) underpinning Guided Inquiry Design. I had another ‘wow’ moment (Galimi, 2020, May 23) after trying out Karen Bonnano’s F-10 Core Skills and Tools. While I was familiar with some, I had never heard of or used many of the tools suggested. GI combines the development of IL and ICT skills seamlessly, particularly BYOD and for learning to extend beyond the classroom walls (Galimi, 2020, May 22).

I can also see the Big6 model being useful in my practice as a TL, the implementation and intervention required would be less involved compared with GI. Students would receive the benefit of ‘metacognition,’ an awareness of mental states and processes as well as a broad, logical problem solving skill set providing a useful curriculum framework (Eisenberg, 2008, p. 41). However, GI has the ability to propel students to a deeper level of subject area curriculum content and information literacy concepts (Kuhlthau et al., 2007, p. 1).

I was surprised and concerned to learn that neither the Australian curriculum (www.australiancurriculum.edu.au), nor the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) (http://www.acara.edu.au/) include TLS or the role of the TL (Galimi, 2020, May 1). The General Capability, Critical and creative thinking, “favouring inquiry learning and the need for embedding technology in learning” (FitzGerald & Todd, 2018, p.47-48) is welcome, I hope that the role of the TL will be cemented in the Australian curriculum soon. I had wondered how inquiry formed part of the curriculum (Galimi, 2020, April 26), while I have a greater understanding of this now, I do agree that for accountability of 21st century skills to occur, a school wide approach across the curriculum would be a better approach.

While there are many benefits to technology use within the classroom, the recent Growing Up Digital Australia study provided some concerning results (Galimi, 2020, April 29). The current climate of remote learning due to Covid-19 (Galimi, 2020, April 23) has further illuminated the inequity within the Australian school system. How is it possible for all children to become 21st century learners if they do not have the appropriate internet access or computer to access online resources, or in recent times remote learning classes? I hope that a revolution will occur due to Covid-19, where school libraries, TLS and 21st century skills are made possible for all Australian students.

References

Eduwebinar https://eduwebinar.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/curriculum_mapping.pdf

Eisenberg, M. B. (2008). Information literacy: Essential skills for the Information Age . Journal of Library &Information Technology, 28(2), 39-47.

Eisenberg, M. & Berkowitz, R. (1995). The SIX Habits of Highly Effective Students. School Library Journal, 41(8), 22-25.

FitzGerald, Lee. (2018). Guided Inquiry Goes Global: Evidence-Based Practice in Action, ABC-CLIO, LLC.

Garrison, K. L., & FitzGerald, L. (2019, October, 21-25). “One interested teacher at a time”: Australian teacher librarian perspectives on collaboration and inquiry [Paper]. International Association of School Librarianship, Dubrovnik, Croatia.

Kuhlthau, C. C., Maniotes, L. K., & Caspari, A. K. (2007). Guided Inquiry: learning in the 21st century. Libraries Unlimited.

Kuhlthau, C. C., Maniotes, L. K., & Caspari, A. K. (2012). Guided inquiry design: A framework for inquiry in your school. ABC-CLIO, LLC.

Mardis, M. (2017). Librarians and educators collaborating for success: The international perspective.ABC-CLIO, LLC.

Todd, R. J. (2009). School librarianship and evidence-based practice: Progress, perspectives, and challenges. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 4(2), 78-96.