Part A: What makes an effective Teacher Librarian?

Effective teacher librarians are curious, interested and interesting. They wonder, wander and guide students and colleagues through their own wonder/wanderings. Effective teacher librarians blend their understanding of the nature of learning and the structure of the curriculum to maximise learning for each student both in the moment and in the future. Effective teacher librarians maintain current knowledge of available resources suitable for their communities and facilitate access for the right learner at the right time. Teacher librarians aim to provide both a physical and intellectual space for the exploration of all kinds of literacies, rigorous academic exploration, community engagement and mindful recreation. The activities undertaken and promoted there should support that aim. Effective teacher librarians are leaders as well as managers, innovators as well as guides and mentors as well as students. It is in the balance and interaction between all these attributes that the magic may be found.

Jones, G. (2018). The daring librarian mission. https://www.thedaringlibrarian.com/2018/01/how-to-be-teacher-librarian-rock-star.html

The graphic to the right, by Gwyneth Jones from her blog, The Daring Librarian, resonates with me because it puts into simple language the aims to which teacher librarians should aspire.

Part B: Critical Evaluation of Learning

Introduction

I am glad to have undertaken my studies slowly and steadily over the last three years because it has allowed me plenty of time to consider, reflect on my learning, put theories into practice and change, evaluate and refine ideas along the way. I wrote the first post on my ThinkSpace blog, Embarkation (Hahn, 2019, July 8), immediately before beginning my first semester of study so that I might look back from this end and reflect on my thoughts and impressions and how they have changed. In that post, I identified the “vital role a good teacher librarian has in developing the students’ love of learning, appreciation of literature and ability to really think about the information they are gathering” and that “it is also vitally important for TLs to make their available services and skills known and visible to their colleagues, especially their newer colleagues who might benefit most from the leadership and guidance a really good TL can provide”. I had, at that early stage, identified two key elements of the role of TL: developing lifelong love of learning and literature, and advocacy through leadership. I still believe these to be important, but I missed possibly the most vital: forming relationships: relationships with and between colleagues, students and leadership, relationships between people and information and relationships between people and lifelong learning.

Theme 1: Lifelong love of learning and literature

From the outset of my studies I was surprised by the need, expressed multiple times over several subjects, to defend the use of fiction in the curriculum. This surprised me because the place of fiction just seemed so obvious to me – it was like needing to justify the place of oxygen in the air. I have learned since, however, that it is not so obvious to everyone. Reading fiction helps students to develop empathy, explore unknown activities, places and situations safely, and to experience the world through someone else’s eyes. Rita Carter, in the Tedx Talk embeded below, explains succinctly and in everyday language this very concept in a very accessible way.

Journalist Rita Carter on why reading fiction is good not only for individuals but for society as a whole. 28 June, 2018

Lesesne (2003) and Schneider (2016) both write eloquently about strategies teacher librarians, among others, can use to help students become lifelong readers and therefore lifelong learners, citing three main skills needed: knowledge of the student, knowledge of the books and motivational skills to bring the two together. These topics were addressed in ETL503 Resourcing the Curriculum and ETL402 Literature across the Curriculum – two subjects I found to be especially useful in my work as a teacher librarian. The creation of annotated bibliographies is something I have done many times over the last three years and expect to continue.

Recently, I have discovered the Reading Lists tool within our Library Management System, Oliver, that can be used for this purpose, keeping the information accessible to staff at all times. Using this tool, I have been able to create topic based recommended reading lists for both students and staff to use, linking the resource records directly and allowing users the benefit of tools such, reserve, request and review options as well as the ability to link items directly into their Google Classroom. I have included an example of this, created for a Stage 2 Geography unit of work, Places are Similar and Different. Use of these tools relies on the ability of staff to access it. This has involved offering staff training and refreshers at planning days and staff admin meetings as well as personal tutorials at a point of genuine need when staff come to the library seeking such information, and teaching students how to use the tools during their library lessons each week.

ETL501 The Dynamic Information Environment offered the opportunity to learn not just about creating physical spaces for learning, but also creating digital spaces for learning. I found the development of Library Research Guides to be particularly valuable. I have been creating such guides for a while, but this subject taught me a new way to go about it, making the resources so much more useful and valuable to students and staff alike.

I have included below two examples: the first from before I undertook ETL501 and the second from after. The linear, guided manner in which the later one is designed, along with the inclusion of items such as a glossary, recommended search engines and a feedback form for users to supply their suggestions and thoughts are things I had never considered prior to undertaking this subject. The later of these LRGs along with several others created since to support Stage 2 and 3 units of work have been received to much acclaim by staff that use them and have received thoughtful and constructive feedback allowing me to continually improve the quality of resources I can offer through the library. Staff have commented particularly about the integration of information literacy skills and how they include resources that teachers would not have considered on their own.

The idea of ensuring resource guides included resources that teachers and students would have been unlikely to find on their own was first introduced in ETL402 Resourcing the Curriculum, and reiterated in many other subjects I have taken throughout my studies and I recently had the opportunity to see this idea in action at a public library while on professional placement. The outreach librarian was selecting resources for patrons who had opted for the home delivery service available to less mobile members of the library. She too was keen to include in the selection a resource that the patron would hopefully like, but may not have chosen themselves. She used tools such as the Tourist Map of Literature

website (pictured to the right) to find authors similar to those the patron had read and enjoyed previously. This is a tool I am now using in my practice as a teacher librarian.

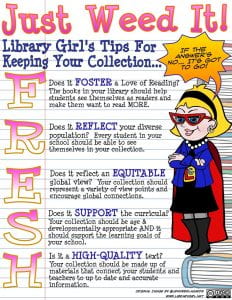

In order to ensure there are resources available to suit the needs of the school community, it is necessary to have in place a strong collection development policy, including a procedure around selection and deselection. This concept was first introduced in ETL503 Resourcing the Curriculum and has been developed during other subjects along the way. When I first began work as a teacher librarian in my school, I came to see that the collection was out-dated, old and in poor condition. As a result, usage of the library resources was limited. I have taken the ideas learned especially in ETL402, ETL501 and ETL503, to begin updating the collection. During my study, I was introduced to the idea of using analytical reporting to judge the health of the collection. I decided to implement this in my library, discovering quickly that the average age of the collection was over 20 years – this did not surprise me, unfortunately. I knew that the first task was to undertake a weed of the worst offenders. I established a ‘shelf of shame’ in my office consisting of items removed from the collection far too late to remind me of the need to weed and I have found it a useful tool to share with others when they question why I am “getting rid of so many books”.

Image by Jennifer LaGarde

www.librarygirl.net

Shared under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike (CC BY-NC-SA)

I have included to the left a graphic from the blog of Jennifer LaGuarde (2020, April 30) explaining her approach to weeding. It resonates with me as it puts into positive language the desirable features of school library collection against which candidates for weeding may be compared.

Theme 2: Advocacy through leadership

ETL 504 Teacher Librarian as Leader introduced terms that can be used to describe phenomena previously observed – developing a deeper understanding of the styles of leadership available and the effect of each. Having the language to discuss and describe these concepts helps to nuance my understandings. In this way, I can be more deliberate in my choices around which strategies I employ in different circumstances and also to recognise and support the choices made by other leaders in my workplace.

Just as it is important for teacher librarians to provide a safe “third space” (Korodaj, 2019) for students, it is important to also provide this for staff. Change leadership (and I deliberately choose the word leadership rather than management) has been a feature of the work of schools in recent times – through the pandemic and the resulting pedagogical changes, as well as with the introduction of new syllabus documents in NSW schools and the challenges faced by many schools with staffing and casual relief. Many colleagues have expressed to me that, while they understand the features of the new syllabus documents, and appreciate the changes they are to make, they need more professional development in what it all looks like in reality. These conversations have taken place in the “cone of silence” – When the library office door is closed, information shared and discussed does not leave the room. By creating this safe space for staff, I aimed initially to give them a place to vent. It also allowed me to learn about what they need and how I can support them for the betterment of student learning. In my blog post, Module 3.1: Stress (Hahn, 2021, March 20), drawing on the work of Cross (2015) and Clement (2014), I explored how servant leadership such as described above and by Burkus (2010), might help to alleviate some of the stress teachers encounter. A secondary objective of this work is to help colleagues recognise, value and support contributions of the library to the life of the school, thereby activating third-party advocacy in the manner described by Kachel et al (2021).

The school library and teacher librarians are in the privileged position of having a big-picture view of the curriculum, activities and events of the school as a whole and can place them in the context of the school’s strategic plan thereby identifying areas of common interest to different groups within the school and invite them to collaborate. This relies, however, on teacher librarians actively seeking to be involved in the teaching and learning cycle of the various teams across the school, the danger lying in the alternative, described by Sturge (2019) as “a revolving door of classes” (p.26) wherein teacher librarians become isolated, and miss opportunities to address issues of information literacy at a point of genuine need – that is, finding authentic moments to address skills and knowledge contained within the Information Fluency Framework when they are actively needed by students to complete tasks required for other subjects. It is in this real-world use of skills that true life-long learning can occur. Because of this, it is vital that teacher librarians employ their instructional leadership skills and teacher leadership skills in order to mobilise and activate colleagues and others in advocating for the library, much in the manner described by Bonanno and Moore (2009). An excellent example of this is found in the Students Need School Libraries campaign started and headed by Holly Godfree. This group provides, among many resources, flyers and promotional materials that are made available for teacher librarians to share with their communities, assisting teacher librarians to harness the advocacy power of school communities in support of their library program.

Instructional leadership has been a feature of my work in recent times, especially around the use of technologies to support educational access by students with learning difficulties and additional needs. By adjusting my fixed timetable in collaboration with interested class teachers, I have been able to provide team-taught lessons introducing and utilising assistive technologies such as Immersive Reader with all the students in a class, demonstrating for students how and when such technologies may be useful to them, at the same time demonstrating to teachers how employ universal design in conjunction with the available tools to allow all students to engage with curricula on an equal basis. By working specifically with targeted, interested teachers, I have been able to harness their connections and relationships to further advocate for the services and skills a strong library program can provide.

Theme 3: Relationships

Brighten and define the purpose of areas with rugs

The Third Space is also vital for students. In ETL 501 The Dynamic Information Environment, I explored the development of effective spaces both physically and digitally. One of the main take-aways from this subject was the need to consider how the designed spaces impact and are impacted by the people who use them. I had not previously considered that, by providing group vignettes, hidden individual reading areas, large open whole class spaces and interactive displays could encourage students to behave and interact differently with the information they are using. To this end, I have added to the library I work in, rugs that define the purpose and use of different areas, a variety of types and groupings of seating, flexible work table orientations,student work examples and wall displays that teach. I am still working on rearranging shelf configurations and technology storage to maximise use and availability.

I approach interactions with students with humour where appropriate to encourage them to see me as approachable; high expectations of behaviour so that I avoid unnecessary unpleasantness; openness and patience to encourage students to talk to me about their needs and thoughts. I provide interesting activities at lunchtime in a climate controlled environment to encourage students to come into the library voluntarily and view it as a pleasant and desirable place of interest. In this way, I hope to engender a belief that the library is a welcoming, interesting place in which ideas and information can be explored and discussed in a rigorous but non-threatening way. The lego building vignette pictured to the right is used at lunchtimes.

The collaborative puzzle

Students are invited to build on to constructions made by other students in previous sessions. Once firm boundaries were established around the protocols for use of the space, students have been engaging positively and enthusiastically at lunchtimes. They are (mostly) able to leave it alone during class time and a helpful side effect has been drawing student’s attention to the sometimes neglected early chapter book collection housed around the lego area. This has seen circulation of this collection rise by 23% in the 6 months since establishment of the lego area.

Community building activity: collaborative lego construction

Jigsaw puzzles (pictured to the right) have also been used for collaboration and community building among students. It is my intention that these collaborative activities will encourage disparate groups of students to engage in shared activities, getting to know each other better and learning to engage positively with students from other backgrounds and interest groups, contributing to the development of a cohesive school community that forms part of the school’s medium to long term goals. An additional advantage has been providing activities and environments that promote wellbeing for our students with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) (Saggers & Ashburner, 2019). Puzzles are selected based on the special interests of these students and well-ordered, usually quiet and minimally stimulating areas are used to provide these students with an environment they can use to calm and re-regulate themselves as needed. This encourages all students to see the library as a peaceful, interesting and pleasant place to learn and to practise interacting with others. Visual cues, noise-cancelling headphones and positive, calm relationships are also used to engage our students with ASD.

Part C: Developmental Evaluation

The ALIA/ASLA Standards of Professional Excellence for Teacher Librarians (ALIA, 2004) provides the professional knowledge, practices and commitments that teacher librarians should strive to achieve. A key development in the professional knowledge area during my studies has been the introduction of the

Information_fluency_framework which aims to “articulate the work of the teacher librarian (p.4), drawing together elements of the Australian Curriculum General Capabilities and NSW Syllabus documents to make plain for all school staff and leadership the skills and understandings that teacher librarians teach and where they fit in the curriculum. This important document, recently released and only pertinent to NSW schools, has not been a part of my studies at all. As a result, I have needed to identify and source professional learning opportunities outside of the University, such as PLCC After Hours Professional Development, spearheaded by Gina Krohn (see left). Continual engagement with professional networks of teacher librarians and alumni groups is vital to identifying opportunities to continually develop my skills and understandings around pedagogy and curriculum developments. An area I would like to focus on in the near future is utilising educational technologies to enhance teaching and learning opportunities, with a specific focus on developing the skills of kindergarten to year 2 students and their teachers.

ALIA-ASLA Standard 3.4 Community responsibilities requires teacher librarians to participate as members of professional communities. Over the last three years that I have been studying and working as a teacher librarian, I have joined several network groups, both formal, such as becoming a student member of ALIA (which I will continue into a professional membership once I graduate) and joining the Teacher Librarian Network in Northern Sydney through my employer, and informal, such as joining social media groups for Teacher Librarians both in NSW and around the country and world. I have found there the most supportive and collaborative group of colleagues I have found so far in the education industry. This spirit of cooperation and collegiality is something I strive to replicate and actively promote in my workplace.

Standard two requires teacher librarians to provide exemplary information and library services. Recently, my school held a festival of reading for Education Week. I was able to demonstrate and explain to parents and staff alike the services I offer as teacher librarian. I was able to demonstrate some of the Library Resource Guides developed to support collaboratively taught units of work in Stage 2 and 3, show teachers and parents how to access the Library’s digital collections from their mobile device and explain the reference and information services available in the Library.

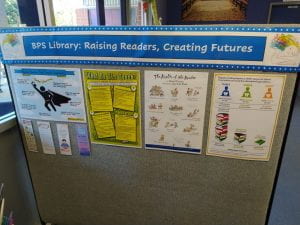

Backing board used as a conversation starter at the Festival of Reading

Pictured to the right is the backing board used during this presentation. I did not specifically refer to it, but used it to draw attention to the role of the teacher librarian and to provide conversation starters with parents. This was a highly successful morning and one of the immediate benefits I can see is dramatically increased circulation of our digital collection, and three new requests for collaboration from teachers who have not previously engaged with library services. An area I would like to develop more within this strand of the professional standards is evaluation of the library’s collection. To this end, I have enrolled in a course offered by Softlink (providers of Oliver Library, our LMS) that will address use of analytical reporting in the school library. Other sources of ongoing professional learning are SCIS Professional Learning Webinars and Primary English Teachers Association Australia courses and conferences which often offer content relevant to teacher librarians.

References

Australian Library and Information Association (ALIA). (2004). Standards of professional excellence for teacher librarians. https://read.alia.org.au/file/647/download?token=6T4ajv0c

Bonanno, K. & Moore, R. (2009). Advocacy: Reason, responsibility and rhetoric. https://kb.com.au/content/uploads/2014/08/Keynote-Advocacy.pdf

Burkus, D. (2010, April 1). Servant leadership theory. In DB: David Burkus. http://davidburkus.com/2010/04/servant-leadership-theory/

Clement, J. (2014). Managing mandated educational change. School Leadership & Management, 34(1), 39-51. https://doi: 10.1080/13632434.2013.813460

Cross, D. (2015). Teacher well being and its impact on student learning [Slide presentation]. Telethon Kids Institute, University of Western Australia. http://www.research.uwa.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/2633590/teacher-wellbeing-and-student.pdf

Jones, G. (2018). The daring librarian mission. https://www.thedaringlibrarian.com/2018/01/how-to-be-teacher-librarian-rock-star.html

Kachel, D. E., DelGuidice, M. & Luna R. (2012). Building champions in the school community. In D. Levitov (Ed.), Activism and the school librarian: Tools for advocacy and survival. (pp. 85-98). ABC_CLIO, LLC.

Korodaj, L. (2019). The library as ‘third space’ in your school: Supporting academic and emotional wellbeing in the school community.Scan, 38(10). https://doi.org/10.3316/aeipt.226270

LaGuarge, J. (2020, April 30). BFTP: Keeping your library collection smelling F.R.E.S.H! The Adventures of Library Girl. https://www.librarygirl.net/post/bftp-keeping-your-library-collection-smelling-f-r-e-s-h

Lesesne, T. (2003). Making the match: The right book for the right reader at the right time, grades 4-12. Stenhouse Publishers.

Saggers, B. & Ashburner, J. (2019) Creating learning spaces that promote wellbeing, participation and engagement: Implications for Students on the autism spectrum. In Hughes, H., Franz, J. & Willis, J. (eds.), School Spaces for Student Wellbeing and Learning. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-6092-3_8

Schneider, J. J. (2016). The right book for the right reader at the right time. In The Inside, Outside, and Upside Downs of Children’s Literature: From Poets and Pop-ups to Princesses and Porridge (p. 98-158). https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/childrens_lit_textbook/6/

Sturge, J. (2019). Assessing Readiness for School Library Collaboration. Knowledge Quest, 47(3), 24–31.