One of the exciting yet challenging features of the school library is change. The speed of change. The pervasiveness of change. The digital revolution (O’Connell, Bales and Mitchell (2015) that has swept the world has transformed the information landscape and the people who inhabit it. Bringing new formats, digital content, changing publishing models, shrinking print collections, increasing digital collections. But it is still all for the same purpose. The school library still exists to help students find, create and explore ideas (Lamb 2015), to assist students to learn to navigate the information landscape confidently, critically and efficiently. Central to that purpose is the development of a comprehensive, balanced and accessible collection. And central to that is the collection development policy.

We all share the ultimate destination: we want students to be life-long learners. Capable, confident, efficient, ethical and flexible thinkers. While the end destination is the same for all schools, the scenery, route and landmarks are all different. Our approach to collection development and management must be reflective of the community in which we work and the goals and aspirations of that community. It is the responsibility of the teacher librarian to ensure that the library’s policies and procedures support and implement the mission of the school (ALIA and ASLA 2005).

The elements of a collection development policy allow teacher librarians to assess the state of the collection presently, posit the ideal state of the collection and formulate a plan to move towards that goal. I discussed collection evaluation strategies in my blog post, Collection Evaluation. One of the challenges faced by teacher librarians is developing a strong collection that supports the needs, wants, expectations and interests of the school community now and is also flexible enough to be useful as technology and pedagogy continue to develop. Loh and Sun (2019) argue that it is the preferences and interests of the readers themselves that determine whether print or digital resources are more effective. Print is heavy, not updated and takes up valuable shelf real estate, yet students prefer it in some circumstances (Copyright Agency, 2017; Johnston& Salaz, 2019). But what about picture books? Richter and Courage (2017) found that younger readers were more engaged in e-books than in print. It is therefore important for the school library to offer a variety of formats and delivery methods so that readers of all persuasions might access information in their preferred format. This should be reflected in the goals and selection criteria of the collection development policy.

Along with a diversity of formats, the collection development policy should reflect the desire to create a collection that represents a diversity of viewpoints (Disher, 2014). All students have the right to see themselves reflected in the characters, stories and problems they read about (Braxton, 2018). Recognising themselves in characters that face hardship and overcome challenges encourages them to do the same when they are experiencing difficulty. Seeing the world through many different lenses allows students to develop empathy and intercultural understanding (Brown, 2016; Veltze, 2004).

Are school libraries and teacher librarians to disappear as teachers and students access resources directly online? Finding reliable, accessible and authoritative information online can mean sifting through a lot of unreliable and irrelevant resources in order to find what is needed. I wrote about this in my discussion post in Forum 2.4b and in my comments in Forum 2.4a on the work of Michelle Wheeler. Strong selection criteria combined with reliable selection aids ensure that resources included in the collection are reliable, authoritative and relevant to the school community. Yet, to make sure resources selected meet the needs and interests as closely as possible, it is desirable to include the school community in decision making processes (Viner, 2016). I discussed some strategies for this in my blog post, With Whom the Buck Stops. Regular review of the collection development policy and the selection criteria is desirable in order to ensure the collection continues to meet the needs, wants, interests and expectations of the school community. I discussed this in my blog post, Selection and Deselection. Part of the review cycle should include an evaluation of the collection. Doing this regularly is especially important in a time of rapid change to curriculum such as has been seen since the introduction of the Australian Curriculum and the related state syllabus documents. Keeping abreast of changes in syllabus documents and pedagogical developments allows teacher librarians to ensure resources and services provided remain up-to-date.

Changes in technology available in schools has and will continue to be rapid (Domeny, 2017). This has implications for the teacher librarian in determining how the development of digital collections will proceed. Changing software and hardware can mean that resources quickly become unusable, for example, many devices can no longer access CD and DVD resources as they do not have the necessary drives. Software that is developed for older operating systems may not be compatible with newer versions. Resources that can be accessed by iPads may be inaccessible to Android devices and so on. This should be kept in mind when selecting resources and access patterns: what is cutting edge now will likely be obsolete in five years time. The changing technology space brings some exciting new tools and pedagogies but it also brings new safety concerns. Gillies (2017) argues that digital security is a major concern in schools that requires more the virus protection, firewalls and content filtering. She advocates placing greater attention on digital citizenship and cyber security. These are, arguably, part of learning to navigate the digital information environment safely and effectively. The challenge is to keep students safe from inappropriate content without straying into censorship (Rumberger, 2019). Here, too, we must be ever mindful of the context. What is appropriate in one school may be positioned just over the line in another. I considered this in my discussion post in forum 6.2.

Part B References

ALIA & ASLA. (2005). ALIA-ASLA policy on school library resource provision. Retrieved from https://www.alia.org.au/about-alia/policies-standards-and-guidelines/alia-asla-policy-school-library-resource-provision

Brown, D. (2016). School libraries as power-houses of empathy: People for loan in the human library. International Association of School Librarianship.Selected Papers from the …Annual Conference, , 1-10. Retrieved from https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.csu.edu.au/docview/1928619177?accountid=10344

Copyright Agency. (2017, February 28). Most teens prefer print books [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://www.copyright.com.au/2017/02/teens-prefer-print-books/

Domeny, J. V. (2017). The relationship between digital leadership and digital implementation in elementary schools (Order No. 10271817). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (1896954900). Retrieved from https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.csu.edu.au/docview/1896954900?accountid=10344

Disher, W. (2014). Crash course in collection development. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com

Gillies, A. (2017). Creating a healthy digital environment for 21st century learners. Independence, 42(2), 60-61.

Johnston, N., & Salaz, A. M. (2019). Exploring the reasons why university students prefer print over digital texts: An Australian perspective. Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association, 68(2), 126-145.

Lamb, A. (2015). Makerspaces and the school library part 1: Where creativity blooms.

Loh, C. E., & Sun, B. (2019). “I’d still prefer to read the hard copy”: Adolescents’ print and digital reading habits. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 62(6), 663-672.

Oberg, D., & Schultz-Jones, B. (eds.). (2015). IFLA school library guidelines, 2nd revised edition. Den Haag, Netherlands: International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions. Retrieved from https://www.ifla.org/files/assets/school-libraries-resource-centers/publications/ifla-school-library-guidelines.pdf

O’Connell, J., Bales, J., & Mitchell, P. (2015). [R]Evolution in reading cultures: 2020 vision for school libraries. The Australian Library Journal, 64(3), 194-208. doi:10.1080/00049670.2015.1048043

Richter, A. & Courage, M. L. (2017). Comparing electronic and paper storybooks for preschoolers: Attention, engagement, and recall. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 48, 92-102.

Rumberger, A. (2019). The elementary school library: Tensions between access and censorship. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 20(4), 409-421.

Veltze, L. (2004). Multicultural reading. School Library Media Activities Monthly, 20(9), 24-26,41. Retrieved from https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.csu.edu.au/docview/237132103?accountid=10344

Viner, J. (2016). Collaboration : school libraries. Synergy, 14(2).

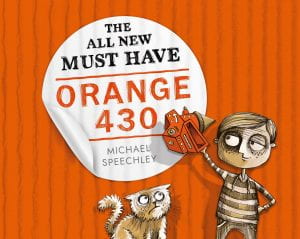

er “The All New Must Have Oran

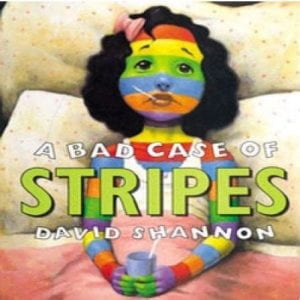

er “The All New Must Have Oran ge 430″ by Michael Speechley – an exploration of the dangers of consumerism. Or “A Bad Case of the Stripes” by David Shannon (be yourself)

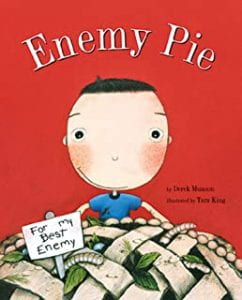

ge 430″ by Michael Speechley – an exploration of the dangers of consumerism. Or “A Bad Case of the Stripes” by David Shannon (be yourself) , “Enemy Pie” by Derek Munson (kindness is desirable), “

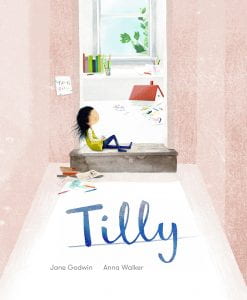

, “Enemy Pie” by Derek Munson (kindness is desirable), “ Tilly” by Jane Godwin and Anna Walker (things – or people – who are lost to us can be kept alive in our hearts and memories). A great many books for children are written as instructive, improving or persuasive texts. Many are explorations of societal norms, problems or issues. Books written for adults do not miss out on this treatment either, and neither they should. While the improving aspects of children’s literature may be less direct than perhaps it was in the past, it is still an important feature of all literature – it explores the nature and development and state of being of us.

Tilly” by Jane Godwin and Anna Walker (things – or people – who are lost to us can be kept alive in our hearts and memories). A great many books for children are written as instructive, improving or persuasive texts. Many are explorations of societal norms, problems or issues. Books written for adults do not miss out on this treatment either, and neither they should. While the improving aspects of children’s literature may be less direct than perhaps it was in the past, it is still an important feature of all literature – it explores the nature and development and state of being of us.