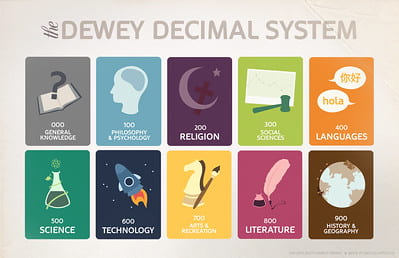

The manner of locating resources by (A) natural language subject headings, (B) controlled vocabulary subject headings within libraries, or (C) standardised classification numbering systems such as ‘Dewey Decimal Classification’ (DDC), or the Library of Congress Classification (LCC,) (or in the form of genrefication of a collection) shows that the vocabulary for describing the ‘subject’ of a resource are all paramount to FRBR element of ‘location’ of a resource.

According to Hider (2018) subject headers, thesauri, classifications are all deceptively subjective, laborious, costly and difficult to maintain, while natural language can be too relative, varied and ambiguous (Hider & Harvey, 2008). So, how do we describe the subject of an item in a (universal) way that our patrons can locate what they need?

An ABC of important terms and their definitions from the modules and readings:

(A) Natural Language / Uncontrolled Vocabularies

- Uncontrolled vocabulary: subject headings &/or descriptors created from natural language, derived from the information resources/authors which are often more up to date, common terms that are more familiar for users; Natural language / uncontrolled vocabularies better enable the tasks of keyword searching, records enhancement and automatic indexing (Hider & Harvey, 2008, p.154-155).

- Key word searching: the method by which a user searches the library collection on the information retrieval system, usually via the title, author, subject, series or a mixture of these (Hider & Harvey, 2008, p. 155).

- Boolean operations: search terms that improve the chance of a match as they include word proximity and word adjacency (Hider & Harvey, 2008, p.155); (See also below “Boolean logic: different terms are combined in a single search using ‘AND’, ‘OR’ and ‘NOT’ (Hider, 2018, p.178).”

- Truncation: the abbreviation of search terms using the # symbol; improving the chance of successful searching because the number of results increases (Hider & Harvey, 2008, p. 155).

- Bibliographic records enhancement: utilising natural vocabulary search functions to include the subject indicative key words within resource abstracts, contents and summaries (Hider & Harvey, 2008, p.156-157).

- Abstracts: A brief, accurate, unambiguous, objective representation of the contents of a document or presentation, usually found in research journal databases; They are usually written after an article has been created and research finalised, and can be indicative / descriptive (indicating specific information found in the article), informative (summarising the data in the article), or critical (making a judgement about the quality of the article contents) (Hider & Harvey, 2008, p.159-160).

- Social tagging: Social tagging is indexing performed by controllers and end users; Similar to truncation, particular key words can be given a # or ‘tag’, rather than being added by a controller, the tag is assigned by a multitude of users, which is then searchable, particularly in social media; Social tagging is not regulated and can be inconsistent (Hider, 2018, p.85-86).

- Folksonomies: a natural vocabulary wordplay opposing controlled taxonomy, folksonomies are indexing vocabularies created by end-users, recommended to be used to complement professional indexing (Hider, 2018, p.86-87).

(B) Subject Headings / Controlled Vocabularies

-

- Objectivism: The view that one may need to discover knowledge, but that all knowledge is ‘set’ and universal (Hider, 2018, p. 189).

- Subjectivism: The view that knowledge is (and is therefore organised) based on various perspectives within culture and societies (see also warrant, below) (Hider, 2018, p.189).

- Controlled vocabularies: Standardised / prescribed sets of metadata values to help index, identify or display a collection (or both); Sometimes referred to as knowledge organisation systems (Hider, 2018, p.175).

- Subject / subject header: a particular knowledge domain which is not always easily identified and not objective, and is, in fact a matter of individual subjective judgement (Hider, 2018, p.175-176); in which (according to LCSH) the knowledge domain / subject is covered by at least 20% of the resource content (Hider, 2018, p.183).

- Subject description: careful analysis of the content of a resource (Hider, 2018, p. 177).

- LCSH: Library of Congress Subject Headings; A standardised (but continually growing and cross-referenced) list of subject headings used to index the content of all english pubic/academic library collections; The initial term heading (followed by a string of sub-divisions) are created as ‘MARC’ fields that can be searched within ‘OPAC’ (Hider, 2018, p.179-180).

- LCGFT: Library of Congress Genre / Form Terms for Library and Archival Materials which “covers ‘artistic and visual works, cartographic materials, “general” materials (e.g. dictionaries, encyclopaedias), law materials, literature, moving images (films and television programs), music, non-musical sound recordings (primarily radio programs), and religious materials’ (Library of Congress, 2018, in Hider, 2018, p.183).

- SCISshl: Schools Catalogue Information Service (SCIS) subject headings list in Australia / New Zealand provided by Education Services Australia.

- ScOT: Schools Online Thesaurus, descriptors used in support of the SCISshl (headings) (Hider, 2018, p188). Schools Online Thesaurus (ScOT) provides controlled vocabulary subject access to online curriculum content relevant to Australian and New Zealand schools and has also been provided by Education Services Australia.

- Subject thesaurus: a structured, post-coordinated, automated, retrieval, indexing (rather than classifying) compilation tool which uses cross-referenced descriptors in support of the subject headings (Hider, 2018, p.185;190); The standard for the creation of subject thesauri is set by the ISO Standard Thesauri for Information Retrieval (Hider, 2018, p.188); See also ScOT (above), ERIC Thesaurus, STW Thesaurus for Economics, NASA Thesaurus, National Agricultural Library Thesaurus, Aquatic Sciences and Fisheries Thesaurus, Australian Health Thesaurus, Australian Thesaurus of Education Descriptors, British Education Thesaurus, Art and Architecture Thesaurus, & the Thesaurus for Graphic Materials (Hider, 2018, p.187-188).

- Warrant: a subjective (see subjectivism above) way to specify the most likely thesaurus terms that will be used as descriptors for the subject headings, eg. literary warrant or user warrant (Hider, 2018, p.185).

- Facet analysis: the method for studying how the facets (and sub-facets) of particular field of knowledge are structured in concept or labelled in terminology (Hider, 2018, p.185-186).

- Index term: a subject heading’s ‘descriptor’ used for cross referencing purposes (Hider, 2018, p.176).

- Cross-referencing: identified by codes like: UF (use for); BT (broader term); NT (narrower term); and RT (related term) (Hider, 2018, p.181).

- Derived indexing: takes/derives words ‘naturally’ from the document (Hider, 2018, p.176).

- Assigned indexing: takes words from somewhere else, typically from a controlled/standardised indexing vocabulary, and assigns them to represent the document’s content.

- Summary level indexing: main topics are described to represent the resource as a whole (Hider, 2018, p.176).

- Standardised classification scheme: vocabulary used for placing items in a specific location or area on a shelf so that it may be easily located (Hider, 2018, p. 175).

- Controlled vocabulary / controlled subject vocabulary: subject headings lists, subject thesauri, or subject classification schemes that can be qualitative or quantitative (Hider, 2018, p.175).

- Pre-coordination: the strings of terms representing the sub-concepts are coordinated prior to indexing and searching, e.g. Birds-Australia; This method is less restrictive (Hider, 2018, p.177-178).

- Post-coordination: the strings of terms representing the sub-concepts stand alone and are then individually searched, e.g. Australia. Birds; This method is more precise (Hider, 2018, p.177-178).

- Boolean logic: different terms are combined in a single search using ‘AND’, ‘OR’ and ‘NOT’ (Hider, 2018, p.178).

(C) Subject Classification Schemes

-

- Subject classification schemes: careful arrangement of the subject headings into groups/classes using (numerical) notations rather than descriptors (Hider, 2018, p.189-190). Subject classification schemes (using subject division – see ‘100 divisions of DDC’ and ‘LCC scheme overview’ charts below) and subdivision disciplines are a good for classification bibliographically, but if used unilaterally for placing resources on shelves, can result in resources being scattered across the space (Hider, 2018, p.193-195); Furthermore, no other numbers than those provided in the DDC ‘Schedules’ or the 6 ‘Tables’ (see ‘6 Tables of DDC’ image below) may be used; While subject classification is usually for labelling and shelving purposes, they can also be vitally important for searching digital collections, digital museums, musical or audio collections (however, not archival collections as these must be organised by date) (Hider, 2018, p.200-201).

- LCC, ADDC15 & DDC23, UDC: These are subject classification schemes (note above) used in the call number element; They are the Library of Congress Classification, the Abridged Dewey Decimal Classification, currently edition 15 (ADDC15) and Dewey Decimal Classification, edition 23 (DDC23) and the Universal Decimal Classification (UDC) (Hider, 2018, 192-193; 196; 198).

- Call number: The entire notation sequence of numbers &/or letters uniquely identifying a resource, making it easier to locate or find on the shelves (Hider, 2018, p.197).

- Disciplines of subject classification schemes: The synthetic means by which the subject classification scheme (such as DDC, UDC, or LCC – used by Trove) is organised, similar to subject headings, but is more aligned with the resource’s purpose, rather than what the resource is about or how it will be used; (Hider, 2018, p.193)

- DDC: Dewey Decimal Classification;

- LCC: Library of Congress Classification using disciplines and a hierarchical notation system, similar to the DDC, except the LCC uses letters and numbers; the LCC and subject headings were created in 1897 based on the ‘Cutter Expansive Classification’/’Cutter numbers’ which create a specific position for each item within a class (see the ‘Summary of LCC’ image below) further expanding using ‘auxiliary tables’ (Hider, 2018, p.196-197).

- UDC: Universal Decimal Classification; a French first attempt at universal bibliographic control across all recorded knowledge (not just American based knowledge) particularly science and technology converted to English in 1980 but still not widely used in English speaking countries; (Hider 2018, p. 198).

- Subject classification schemes: careful arrangement of the subject headings into groups/classes using (numerical) notations rather than descriptors (Hider, 2018, p.189-190). Subject classification schemes (using subject division – see ‘100 divisions of DDC’ and ‘LCC scheme overview’ charts below) and subdivision disciplines are a good for classification bibliographically, but if used unilaterally for placing resources on shelves, can result in resources being scattered across the space (Hider, 2018, p.193-195); Furthermore, no other numbers than those provided in the DDC ‘Schedules’ or the 6 ‘Tables’ (see ‘6 Tables of DDC’ image below) may be used; While subject classification is usually for labelling and shelving purposes, they can also be vitally important for searching digital collections, digital museums, musical or audio collections (however, not archival collections as these must be organised by date) (Hider, 2018, p.200-201).

![Hider, P. (2018). The 6 Tables of DDC [Image] in Information Resource Description / Creating and Managing Metadata. Vol. Second edition. Facet Publishing. p195](https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/croe/files/2020/10/Hider-P.-2018.-The-6-Tables-of-DDC-Image-in-Information-Resource-Description -Creating-and-Managing-Metadata.-Vol.-Second-edition.-Facet-Publishing.-p195.png)

(Hider, 2018, p.196)

(Hider, 2018, p.196)

Thoughts and musings before and after completing the final assessment:

- In modules 4 & 5, while reading Hider (2018) p. 201-205, I tried to understand how a taxonomy is different from a classification system versus an ontology system, but sorry, my brain would not absorb it and I feared I had reached max capacity for Hider.

- Throughout this session, I could not manage the multitude of forum posts for this subject. It was far more than any other subject (and I’ve completed all but 1 elective at this point) and was very minimal in actual ‘discussion’ – more used as a place for students to post their answers to the tasks. I recommend the powers that be consider using a series of (perhaps unmarked but compulsory) ‘quizzes’ or something for the tasks other than forum discussions, particularly if the cohort is medium to large in future.

- When I started this degree I expected to do this class first. I think I am glad that I didn’t. I can see the relevance, but the content is very academic and I’m glad I did it (almost) last. In the beginning of this class I felt like I was filling my brain with things that would be taking up what is very valuable and limited realestate, and I only just changed my mind after completing the second assessment. (This may be compounded by the fact that I am not presently, nor have I ever, worked full time as a teacher librarian and everything I am trying to learn from copious amounts of reading is not yet applicable to my real world context.)

- As I read (and read) the first assessment feedback, the main thing that I learned was that the lecturer and the text book author for the course were both very very much smarter than I. (This is certainly, without question, definitely true. Yet, I think it is a reflection on the course that I feel this way. Is it far too academic, far too wordy, far too heavy in reading, and, although I got a credit in the first assessment, far too thorough in the marking? Or am I too arrogant? Food for thought.)

- My issue with Research in Practice was exactly the same issue that I had with Describing and Analysing Education Resources and that was: I have spent most of the course trying to dig myself out of the (growth mindset) learning pit and felt out of my comfort zone the entire duration. I was reading and reading and reading. I was reading the texts, the modules and the forum posts (although, as previously stated, found very little with which to engage). I was posting blog posts with my reading notes. I was doing the exercises and checking my answers (generally way off!). I took two weeks off work (on either side of my 2 week prac) to ensure I completed the final assessment, meaning I had a month off work (and financially suffered with my family). And in the end, I learned a fair bit and would consider what I learnt, worth the struggle.

On my way Bitmoji - Finally, now that I’ve done the course and basically finished the degree, I pleased to say that I feel like I understand the concepts and could manage cataloguing. (Enjoying cataloguing, however, might be a fair way into the distance)…Also, I still think Hider (and a few times in the learning modules) need to correct all of the many end of sentence prepositions in the next edition of the textbook. Please. Thank you.

References

Hider, P. (2018). Information Resource Description : Creating and Managing Metadata: Vol. Second edition. Facet Publishing.

Hider, P., & Harvey, R. (2008). Organising knowledge in a global society : Principles and practice in libraries and information centres. ProQuest Ebook Central https://ebookcentral.proquest.com