Resources must be NAVIGATED, Discovered, Identified, Selected, Obtained

In order for an information seeker or library user to effectively navigate a library collection, they must be taught how to use the organisational tools for that setting, such as: catalogues, databases (periodical / citation / image / etc), bibliographies, subject guides / gateways, directories or search engines, to name a few (Rowe, 2019, Module 2.1) this includes staff, parents, students, the general public, etc.

“The arrangement of resources by Dewey Decimal Classification, alphabetical order and, on occasion, by other attributes such as type of material, level of difficulty, and genre, along with the use of indexes and databases, such as the library catalogue, are key tools of information retrieval used in school libraries” (Rowe, 2019, Module 2.1).

Tools and systems

To truely be considered an effective information retrieval organisational system, systems must not simply be based on content (i.e. Google or #tags) but must also be based on the elements of metadata – such as is found in library catalogues and archival finding aids, and must be 1. arranged, 2. labelled and/or 3. indexed (Hider, 2018, p.43).

- Arrangements: by author or by genre? Either way, a standardised protocol (e.g. The Dewey Decimal Classification or DDC) is the first step (Hider, 2018, p.44).

- Labels are also key, either individual resource labels or labelled in groups, using either words or numerical notations for words/subject matter (Hider, 2018, p.44-45).

- Indexing, is a basic information organisational tool for collections or single resources which uses compact, descriptive, efficient and effective metadata which, in turn, allows multiple access points (e.g. title, author, institution, series, numerical identifiers, etc) for end-users/information seekers (and the more points of access = the greater the chance of success) (Hider, 2018, p.46). Indexes can be closed (once-off & static), open (growing & flexible), card (outdated in today’s libraries), or computer ‘bibliographic’ databases (e.g. SCIS) (Hider, 2018, p.47-49). Indexes form the basis for information retrieval organisation systems such as catalogues, bibliographic databases (e.g. library catalogue) / citation databases, museum registers, archival finding aids, content management systems and search engines (Hider, 2018, p.46; 50).

Library catalogues

Around 1970’s-1980’s, OPAC (online public access catalogue) was the first database to take over paper card catalogues, and was a huge international human data entry task using MARC (machine readable cataloging in a standard format) (Hider, 2018, p.52). OPAC/MARC allowed more access points and has continually grown over time to include things like Boolean searching, truncation, and multiple &/or remote access (Hider, 2018, p.52-53). However, it is important to note that more work is needed to make library catalogues designed in the MARC format competitive with Google:

“Perhaps an even greater issue, however, is the scope of library catalogues. Nowadays they represent only a certain proportion of information resources provided by the library, and only a tiny proportion of resources available in the online environment as a whole. As Ruschoff (2010, 62) argues, ‘more lipstick on our catalogs is not going to make our OPACs the search engine of tomorrow’. Since it is clearly impossible for libraries to catalogue all the useful resources now available on the internet, the way forward appears to be for libraries to ensure that their metadata is out there in the wider online environment: if they can’t beat the likes of Google, they need to join them” (Hider, 2018, p.57).

Sharing library catalogues / metadata

Metadata that has been created using agreed standardised protocols such as MARC / RDA, as well as containing the agreed set of elements, it can be used in different information retrieval systems at different institutions, creating ‘bibliographic networks’ and even ‘bibliographic utilities,’ and ‘union catalogues’ offering the benefit of it only having to be created once, saving a great deal of time and expense (Hider, 2018, p111-112; 115).

One such ‘bibliographic utility’ is the SCIS catalogue. Chadwick (2015, p.12) points out that by purchasing their catalogue, schools can save hundreds of data entry hours (and money paying employees) and can obtain a more narrow, school-focussed catalogue (as opposed to the more broad catalogues available from places like the National Library).

However, it is one thing to offer a catalogue to share, and another for that catalogue to be able to transmit over to a setting’s computer system. In order to ‘transmit,’ a setting must have particular protocols, such as Z39.50. “Z39.50 is an ‘application layer network protocol’ covered by the ANSI/NISO Z39.50 and ISO 23950 standards and maintained by the Library of Congress. Application layer protocols provide computer programs with a common language when sharing data across networks. Some well-known application layer protocols include Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) and File Transfer Protocol (FTP). Z39.50 allows a system – usually a LMS – to search and retrieve information from bibliographic databases across the world” (Chadwick, 2015b, paragraph 2).

As well as sharing amongst library databases, various databases and even repositories, archives and museums now share their catalogues with search engines and social media applications, improving their catalogue accessibility (Hider, 2018, p.116). “Libraries, museums, archives, universities and publishers are all coming to realise that their websites are not necessarily the first port of call for information seekers. The reality is that, far more often, search engines such as Google are” (Hider, 2018, p.117).

Which brings to the fore the issue of ‘interoperability’ or the ability of metadata created using MARC’s ability to work in a variety of systems, where, if the metadata is not using the same standardised protocols as MARC, it must be converted into a transmittable format using ‘maps’ and ‘crosswalks’ such as ‘Dublin Core’ or DC (Hider, 2018, p.117-118) and Michael Day has provided a great list of maps and crosswalks for a variety of system conversions.

Library databases as a school hub / Learning commons

Combes (2012, p.6-7) makes a great point: schools should be fully utilising their library catalogue / database / information management system to include all resources, even those not housed in the library, including: “class sets; ‘old’ technology resources such as video recorders and TVs; and ‘newer’ technology such as laptops, e-book  readers, interactive whiteboards, USB sticks and digital cameras as catalogued items.”

readers, interactive whiteboards, USB sticks and digital cameras as catalogued items.”

Furthermore, she also makes the point that the catalogues / databases / information management systems should be exemplary teaching models of web design, utilising the most efficient layout, colours, disability access, displays, navigation, interconnectivity and access points (Coombes, 2012, p.7).

Federated search systems

Hider (2018, p.58-59) pushes this concept of libraries as information hubs a bit further through the use of federated search systems, creating ‘service convergence.’ Federated search systems allow users to search multiple databases simultaneously – much like the CSU library ‘Primo’ or the National Library of Australia’s ‘Trove’ function. However, these rely on 1. access globally (rather than simply to those who pay the registration fee) 2. the various databases to all speak the same ‘language’ in terms of language, syntax and semantics, and 3. the various databases must also use similar ‘standardised’ cataloguing protocols as those used by the library setting(s) (Hider, 2018, p.58-59).

Content management and repository systems: Intranet

The large amounts of digital content organisations are producing is managed via different content management systems, intranet and software or ‘institutional repositories’ of various natures and sizes, which have been amalgamated by staff or peer groups They vary enormously in nature and size and may be new or ‘old’ resources being converted digitally (Hider, 2018, p.64-65). These institutional repositories may have textual content (e.g. academic papers, theses, old newspapers, recipes), audiovisual content (images, videos, sound recordings) or multimedia content (e.g. websites). (Hider, 2018, p.64-65).

Citation databases

Evaluation of our metadata

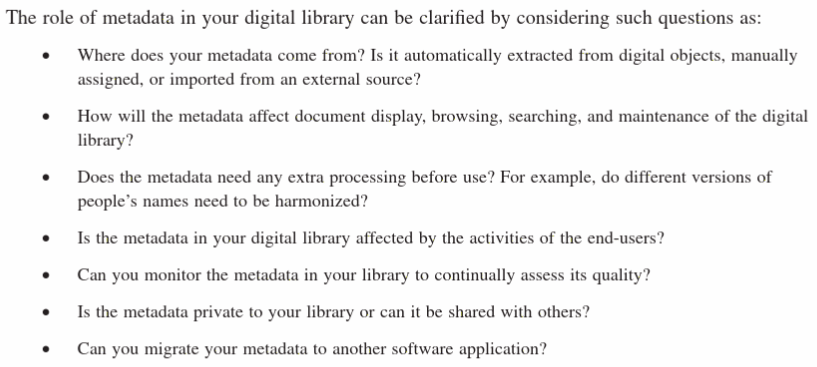

Finally, Witten, Bainbridge, & Nicols (2010 p. 286) provide a list of questions to help librarians evaluate the metadata in their library catalogue:

References and further reading

Chadwick, B (2015). SCIS is more. Connections, 2015(92), 12. https://www.scisdata.com/connections/issue-92/scis-is-more/

Chadwick, B. (2015b). SCIS is more. Connections, 2015(93), 12. https://www.scisdata.com/connections/issue-93/scis-is-more/

Combes, B. (2012). Practical curriculum opportunities and the library catalogue. Connections, 2012(82), 5-7. (On the SCIS home page, click on ‘Connections’ Issue 82, Term 3 2012 & download issue).

Hider, P. (2018). Information resource description: Creating and managing metadata (2nd ed.). London: Facet.

Rowe, H. (2019). 2.1 Tools of library organisation [Learning Module]. ETL505, Interact2. https://interact2.csu.edu.au/webapps/blackboard/execute/content/blankPage?cmd=view&content_id=_3302464_1&course_id=_47581_1

Witten, I. H., Bainbridge, D., & Nichols, D. M. (2010). How to build a digital library (2nd ed.). Burlington, MA: Morgan Kaufmann. Available from CSU eBooks. (‘The scope of digital libraries’, p. 6-9 and ‘Metadata: Elements of organisation’ p. 285-286)