Tag: Learning Commons

Protected: INF506 Assessment 2 – Evaluation and Reflection

Describing and Analysing Educational Resources Module 2

Resources must be NAVIGATED, Discovered, Identified, Selected, Obtained

In order for an information seeker or library user to effectively navigate a library collection, they must be taught how to use the organisational tools for that setting, such as: catalogues, databases (periodical / citation / image / etc), bibliographies, subject guides / gateways, directories or search engines, to name a few (Rowe, 2019, Module 2.1) this includes staff, parents, students, the general public, etc.

“The arrangement of resources by Dewey Decimal Classification, alphabetical order and, on occasion, by other attributes such as type of material, level of difficulty, and genre, along with the use of indexes and databases, such as the library catalogue, are key tools of information retrieval used in school libraries” (Rowe, 2019, Module 2.1).

Tools and systems

To truely be considered an effective information retrieval organisational system, systems must not simply be based on content (i.e. Google or #tags) but must also be based on the elements of metadata – such as is found in library catalogues and archival finding aids, and must be 1. arranged, 2. labelled and/or 3. indexed (Hider, 2018, p.43).

- Arrangements: by author or by genre? Either way, a standardised protocol (e.g. The Dewey Decimal Classification or DDC) is the first step (Hider, 2018, p.44).

- Labels are also key, either individual resource labels or labelled in groups, using either words or numerical notations for words/subject matter (Hider, 2018, p.44-45).

- Indexing, is a basic information organisational tool for collections or single resources which uses compact, descriptive, efficient and effective metadata which, in turn, allows multiple access points (e.g. title, author, institution, series, numerical identifiers, etc) for end-users/information seekers (and the more points of access = the greater the chance of success) (Hider, 2018, p.46). Indexes can be closed (once-off & static), open (growing & flexible), card (outdated in today’s libraries), or computer ‘bibliographic’ databases (e.g. SCIS) (Hider, 2018, p.47-49). Indexes form the basis for information retrieval organisation systems such as catalogues, bibliographic databases (e.g. library catalogue) / citation databases, museum registers, archival finding aids, content management systems and search engines (Hider, 2018, p.46; 50).

Library catalogues

Around 1970’s-1980’s, OPAC (online public access catalogue) was the first database to take over paper card catalogues, and was a huge international human data entry task using MARC (machine readable cataloging in a standard format) (Hider, 2018, p.52). OPAC/MARC allowed more access points and has continually grown over time to include things like Boolean searching, truncation, and multiple &/or remote access (Hider, 2018, p.52-53). However, it is important to note that more work is needed to make library catalogues designed in the MARC format competitive with Google:

“Perhaps an even greater issue, however, is the scope of library catalogues. Nowadays they represent only a certain proportion of information resources provided by the library, and only a tiny proportion of resources available in the online environment as a whole. As Ruschoff (2010, 62) argues, ‘more lipstick on our catalogs is not going to make our OPACs the search engine of tomorrow’. Since it is clearly impossible for libraries to catalogue all the useful resources now available on the internet, the way forward appears to be for libraries to ensure that their metadata is out there in the wider online environment: if they can’t beat the likes of Google, they need to join them” (Hider, 2018, p.57).

Sharing library catalogues / metadata

Metadata that has been created using agreed standardised protocols such as MARC / RDA, as well as containing the agreed set of elements, it can be used in different information retrieval systems at different institutions, creating ‘bibliographic networks’ and even ‘bibliographic utilities,’ and ‘union catalogues’ offering the benefit of it only having to be created once, saving a great deal of time and expense (Hider, 2018, p111-112; 115).

One such ‘bibliographic utility’ is the SCIS catalogue. Chadwick (2015, p.12) points out that by purchasing their catalogue, schools can save hundreds of data entry hours (and money paying employees) and can obtain a more narrow, school-focussed catalogue (as opposed to the more broad catalogues available from places like the National Library).

However, it is one thing to offer a catalogue to share, and another for that catalogue to be able to transmit over to a setting’s computer system. In order to ‘transmit,’ a setting must have particular protocols, such as Z39.50. “Z39.50 is an ‘application layer network protocol’ covered by the ANSI/NISO Z39.50 and ISO 23950 standards and maintained by the Library of Congress. Application layer protocols provide computer programs with a common language when sharing data across networks. Some well-known application layer protocols include Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) and File Transfer Protocol (FTP). Z39.50 allows a system – usually a LMS – to search and retrieve information from bibliographic databases across the world” (Chadwick, 2015b, paragraph 2).

As well as sharing amongst library databases, various databases and even repositories, archives and museums now share their catalogues with search engines and social media applications, improving their catalogue accessibility (Hider, 2018, p.116). “Libraries, museums, archives, universities and publishers are all coming to realise that their websites are not necessarily the first port of call for information seekers. The reality is that, far more often, search engines such as Google are” (Hider, 2018, p.117).

Which brings to the fore the issue of ‘interoperability’ or the ability of metadata created using MARC’s ability to work in a variety of systems, where, if the metadata is not using the same standardised protocols as MARC, it must be converted into a transmittable format using ‘maps’ and ‘crosswalks’ such as ‘Dublin Core’ or DC (Hider, 2018, p.117-118) and Michael Day has provided a great list of maps and crosswalks for a variety of system conversions.

Library databases as a school hub / Learning commons

Combes (2012, p.6-7) makes a great point: schools should be fully utilising their library catalogue / database / information management system to include all resources, even those not housed in the library, including: “class sets; ‘old’ technology resources such as video recorders and TVs; and ‘newer’ technology such as laptops, e-book  readers, interactive whiteboards, USB sticks and digital cameras as catalogued items.”

readers, interactive whiteboards, USB sticks and digital cameras as catalogued items.”

Furthermore, she also makes the point that the catalogues / databases / information management systems should be exemplary teaching models of web design, utilising the most efficient layout, colours, disability access, displays, navigation, interconnectivity and access points (Coombes, 2012, p.7).

Federated search systems

Hider (2018, p.58-59) pushes this concept of libraries as information hubs a bit further through the use of federated search systems, creating ‘service convergence.’ Federated search systems allow users to search multiple databases simultaneously – much like the CSU library ‘Primo’ or the National Library of Australia’s ‘Trove’ function. However, these rely on 1. access globally (rather than simply to those who pay the registration fee) 2. the various databases to all speak the same ‘language’ in terms of language, syntax and semantics, and 3. the various databases must also use similar ‘standardised’ cataloguing protocols as those used by the library setting(s) (Hider, 2018, p.58-59).

Content management and repository systems: Intranet

The large amounts of digital content organisations are producing is managed via different content management systems, intranet and software or ‘institutional repositories’ of various natures and sizes, which have been amalgamated by staff or peer groups They vary enormously in nature and size and may be new or ‘old’ resources being converted digitally (Hider, 2018, p.64-65). These institutional repositories may have textual content (e.g. academic papers, theses, old newspapers, recipes), audiovisual content (images, videos, sound recordings) or multimedia content (e.g. websites). (Hider, 2018, p.64-65).

Citation databases

Evaluation of our metadata

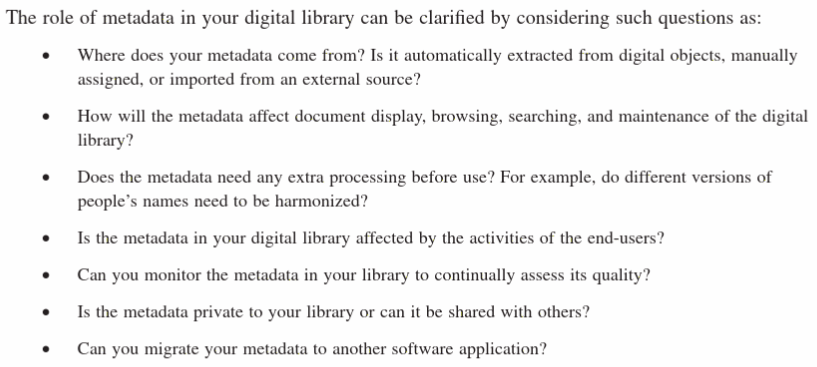

Finally, Witten, Bainbridge, & Nicols (2010 p. 286) provide a list of questions to help librarians evaluate the metadata in their library catalogue:

References and further reading

Chadwick, B (2015). SCIS is more. Connections, 2015(92), 12. https://www.scisdata.com/connections/issue-92/scis-is-more/

Chadwick, B. (2015b). SCIS is more. Connections, 2015(93), 12. https://www.scisdata.com/connections/issue-93/scis-is-more/

Combes, B. (2012). Practical curriculum opportunities and the library catalogue. Connections, 2012(82), 5-7. (On the SCIS home page, click on ‘Connections’ Issue 82, Term 3 2012 & download issue).

Hider, P. (2018). Information resource description: Creating and managing metadata (2nd ed.). London: Facet.

Rowe, H. (2019). 2.1 Tools of library organisation [Learning Module]. ETL505, Interact2. https://interact2.csu.edu.au/webapps/blackboard/execute/content/blankPage?cmd=view&content_id=_3302464_1&course_id=_47581_1

Witten, I. H., Bainbridge, D., & Nichols, D. M. (2010). How to build a digital library (2nd ed.). Burlington, MA: Morgan Kaufmann. Available from CSU eBooks. (‘The scope of digital libraries’, p. 6-9 and ‘Metadata: Elements of organisation’ p. 285-286)

How should educators design / develop / create / manage a digital learning environment (DLE)? (ETL523 Modules 3-5)

Why create a quality DLE?

The reasons behind and processes for creating a quality DLE is much like creating a ‘Learning Commons,’ (which I’ve discussed in two previous posts from ETL503 Resourcing the Curriculum: click here and here).

How do we create a quality DLE?

The article from Chen & Orth (2013) is absolutely amazing, not only because it points out that we must link the school DLE to the home DLE, but also because they outline the key steps to creating a quality DLE starting with 1. forming a group  of stakeholders, creating a shared vision and core beliefs, then 2. training, communicating with or informing all stakeholders, followed by 3. implementing the DLE plan of lessons and concepts of digital citizenship and digital literacy, completing the circle by 4. evaluating and reviewing the DLE regularly.

of stakeholders, creating a shared vision and core beliefs, then 2. training, communicating with or informing all stakeholders, followed by 3. implementing the DLE plan of lessons and concepts of digital citizenship and digital literacy, completing the circle by 4. evaluating and reviewing the DLE regularly.

How do we manage the DLE to foster globally connected learning?

As recommended by Lindsay (2016), we need to:

- Discuss the digital footprints or ‘branding’ of all students and make sure they are using long-term appropriate and culturally sensitive language and images.

- Consider the digital divide and make sure that platforms, discussion tools and global or local connections are provided synchronously (in real time) and asynchronously (offline or pre-recorded).

- Create a DLE that offers students opportunities to authentically and collaboratively engage with peers globally. (Lindsay, 2016).

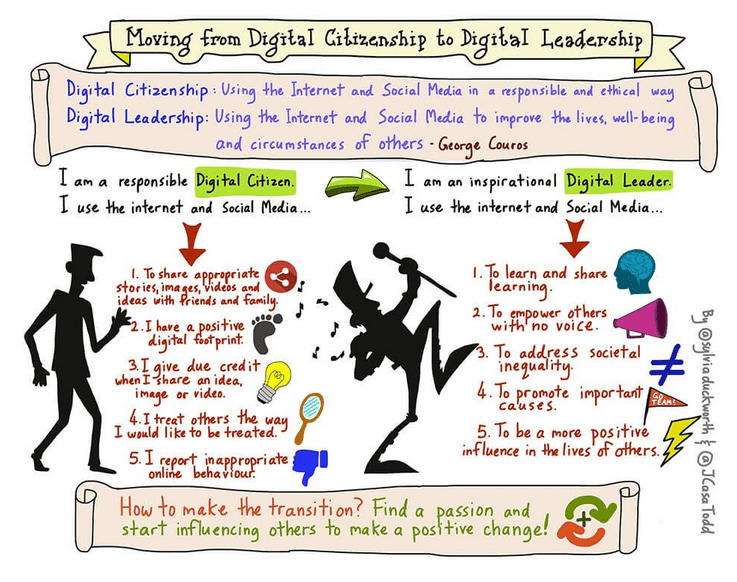

How can we manage the DLE to move students from social media citizens to social media leaders?

References

Casa-Todd, J. (2016). Rethinking Student (Digital) Leadership and Digital Citizenship [Image]. Retrieved from: https://jcasatodd.com/rethinking-student-digital-leadership-and-digital-citizenship/

Lindsay. J. (2016, July 19). How to encourage and model global citizenship in the classroom. Education Week. Retrieved from http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/global_learning/2016/07/how_to_encourage_and_model_global_citizenship_in_the_classroom.html

Chen, E., Orth, D. (2013). The strategy for digital citizenship. NAIS Independent School Magazine (online) http://www.nais.org/Magazines-Newsletters/ISMagazine/Pages/The-Strategy-for-Digital-Citizenship.aspx.

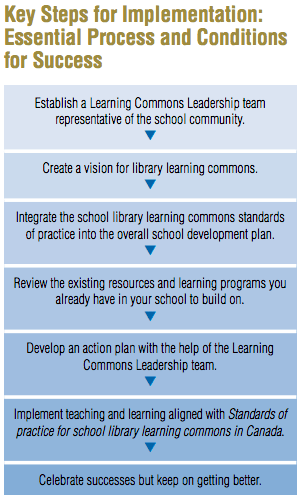

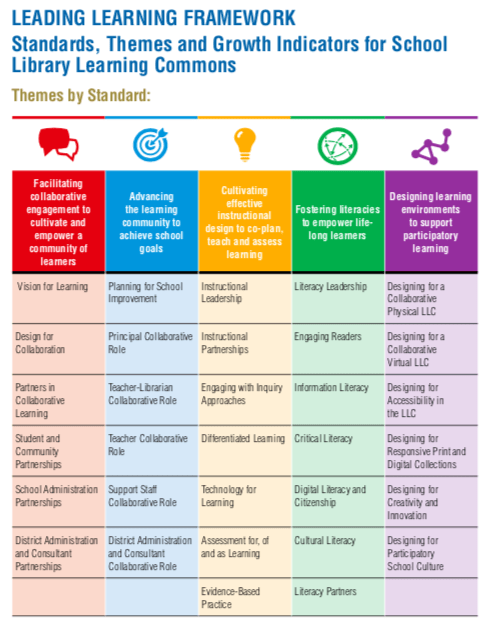

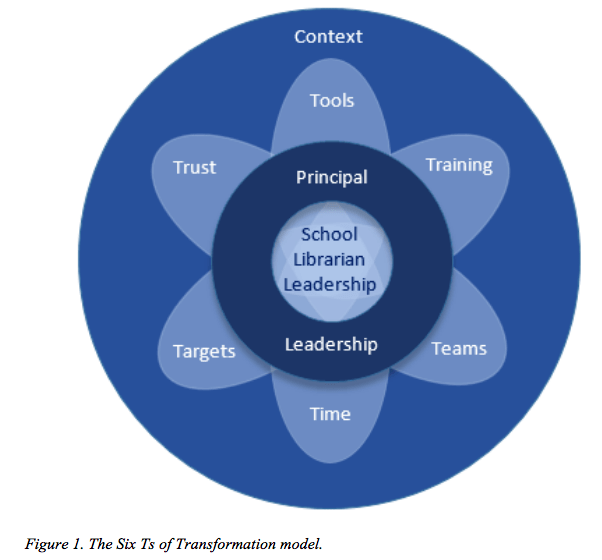

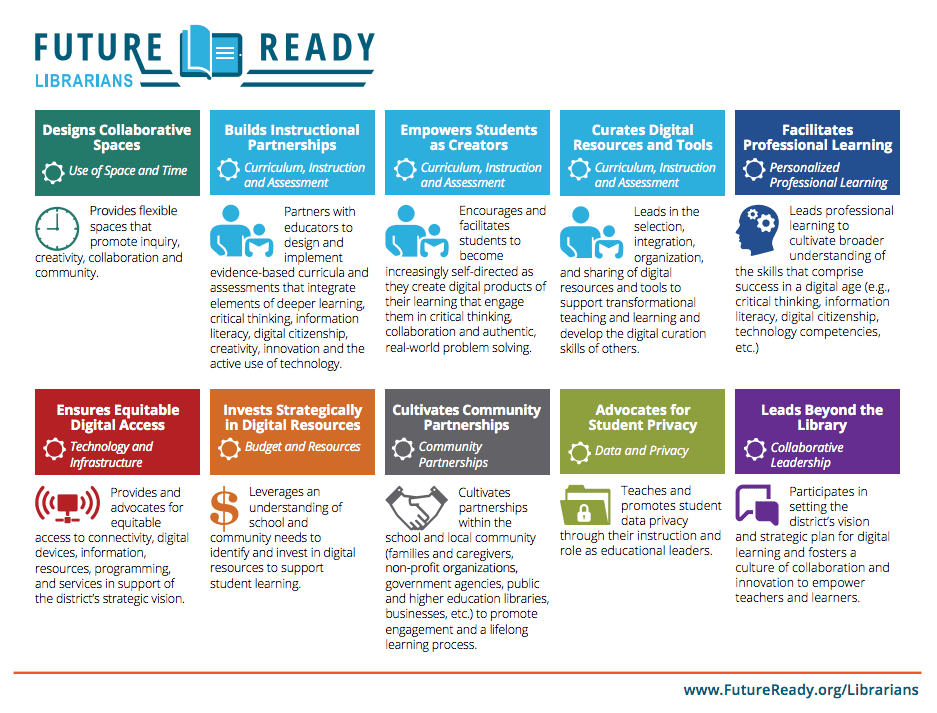

Ideas for Developing a Future Ready Library in Pictures and Graphs

Leading Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Leading Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

These images are great resources and worth remembering and utilising for developing a future ready school library ‘learning commons.’ Where are Australia’s ideas for future ready libraries? Are they just for members of ASLA only or is the ASLA ‘futures’ white paper the only resource we’ve yet to produce? Why are we relying on the resources from North America?

References

Alliance for Excellent Education (2016). Future ready librarians [Image]. In Future Ready Schools. Retrieved from http-/1gu04j2l2i9n1b0wor2zmgua.wpengine.netdna-cdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Library_flyer_download

Baker, S. (2016). Figure 1. The six Ts of transformation model. [Image]. In School libraries Worldwide, 22(1), 143-159. Retrieved from http://www.iasl-online.org/resources/Documents/PD%20Library/11bakerformattedfinalformatted143-158.pdf

Canadian Library Association. (2014). Leading Learning Framework – Standards, Themes and Growth Indicators for School Library Learning Commons. [Image]. In Leading Learning- Standards Of Practice For School Library Learning Commons In Canada. Ottawa, ON- Canadian Library Association. Retrieved from https://apsds.org/wp-content/uploads/Standards-of-Practice-for-SchoolLibrary-Learning-Commons-in-Canada-2014.pdf

Canadian Library Association. (2014). Key Steps for Implementation. [Image]. In Leading Learning- Standards Of Practice For School Library Learning Commons In Canada. Ottawa, ON- Canadian Library Association. Retrieved from http-//clatoolbox.ca/casl/slic/llsop.html

Future Ready Schools (2019). The 7 Gears [Image]. In The Future Ready Framework. Retrieved from https///dashboard.futurereadyschools.org/framework

Protected: ETL401 Assessment 3 Reflective Practice

Information Literacy and Inquiry Based Teaching

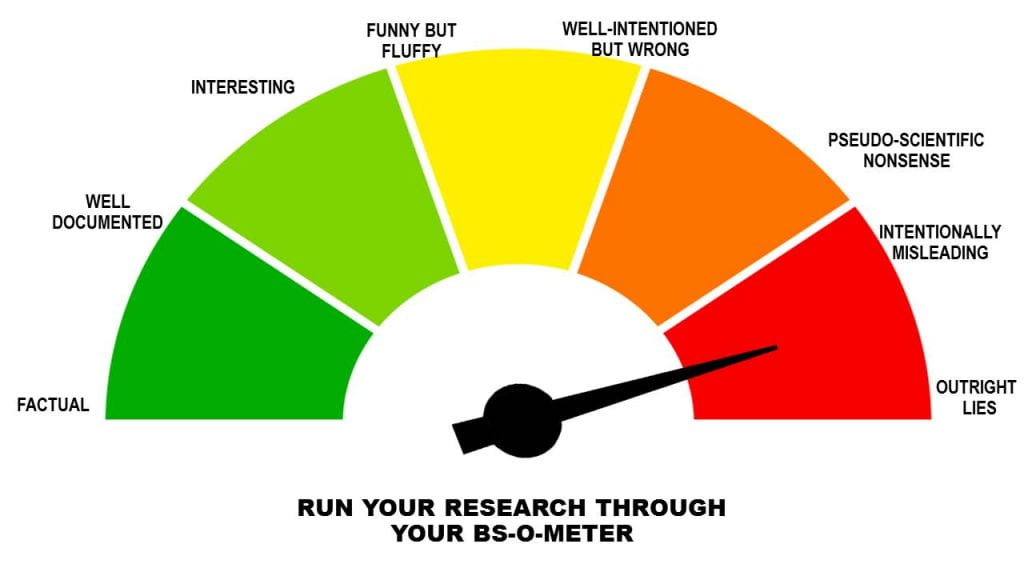

I enjoyed the CRAAP test video , CRAAP rubric and Get REAL rubric, and I was searching for information seeking processes and look what I found! A BS-O-Meter! I can’t remember what forum discussion I was in that mentioned we needed one of these, but voila! Here it is! (I will put it into the forum discussions later):

These devices help us teach the digital literacy aspect of information literacy. What is information literacy? I have grown to understand it better and better and particularly found this quote to be important:

“Understanding information literacy as a catalyst for learning necessitates a move away from exploring textual practices towards incorporating an understanding of the sociocultural and corporeal practices that are involved in coming to know an information environment” (Loyd 2007, pp. Abstract).

Information Literacy is but one form of the the vast aspects of literacy, sometimes referred to as multi-literacies, multi-modal pedagogy or trans-literacy. And basically what it boils down to is that, because of the multiplicity of literacy, educators (including TLs!) need a “pedagogical repertoire” in order to teach all aspects and forms of literacy (Kalantzis & Cope 2015).

I am heartened by the American Library Association (2016): “Information literacy forms the basis for lifelong learning. It is common to all disciplines, to all learning environments, and to all levels of education. It enables learners to master content and extend their investigations, become more self-directed, and assume greater control over their own learning. … …Information literacy, while showing significant overlap with information technology (digital literacy) skills, is a distinct and broader area of competence.”

According to the ALA, (2016) we must help our students become information literate individuals who can:

-

- “determine the extent of information needed;

- access the needed information effectively and efficiently;

- evaluate information and its sources critically;

- incorporate selected information into one’s knowledge base;

- use information effectively to accomplish a specific purpose; and

- understand the economic, legal, and social issues surrounding the use of information, and access and use information ethically and legally” (ALA 2016).

In the Teacher Librarian field, inquiry teaching models have been identified as the best means for enabling information literacy in students.

Maniotes and Kahlthau (2014) explain that inquiry teaching models support the information literacy (and research) for all ages because it is learning centred and focuses on emotionally stimulating questioning and deep understanding rather than product-driven answering and fact finding.

The inquiry teaching model is not presently taught very often or with rigour in most educational settings and this is where, according to Maniotes and Kahlthau (2014), the TL is vital!

In the upper years (age 9 and above) the use of Guided Inquiry Design (GID) is one of the models that is popular. Maniotes and Kahlthau describe it as a framework of inquiry learning design, as represented in 8 sequential phases “Open, Immerse, Explore, Identify, Gather, Create, Share, and Evaluate” (Maniotes & Kahlthau 2014, pp.Abstract).

As I teach the younger years predominantly, I have chosen to work with the Super3 and Big6 Inquiry teaching models and I am hopeful that I can do the pedagogy justice. I am certainly going to give it my best shot!

References

ALA (2016). Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher education. Retrieved from: https://alair.ala.org/handle/11213/7668

Lloyd, A. (2007). Recasting information literacy as sociocultural practice: Implications for library and information science researchers. Information Research, 12(4).

Kalantzis, M. & Cope, B. (2015). Multiliteracies: Expanding the scope of literacy pedagogy. New Learning.

Lloyd, A. (2007). Recasting information literacy as sociocultural practice: Implications for library and information science researchers. Information Research, 12(4).

Maniotes, L. K., & Kuhlthau, C. C. (2014). MAKING THE SHIFT. Knowledge Quest, 43(2), 8-17. Retrieved from https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.csu.edu.au/docview/1620878836?accountid=10344

Young, L. (2019). BS-O-Meter. [Image]. Retrieved from: https://libguides.furman.edu/medialiteracy/framework

Information Literacy, Learning to Read and Reading to Learn

[Reflection of ETL401 Module 5]

Hold your horses cowboy! I’ve just been triggered!

Let’s begin with learning to read and reading to learn. The (ETL401) 5th module jumps straight to reading to learn and doesn’t really mention learning to read, but it is my belief that the two are intrinsically combined and that the education system currently fails students in separating the two (Robb 2011).

Learning to read: This separation of ‘learning to read’ (for some purposes, abbreviated to ‘decoding’-although it is sometimes not referred to as this, the focus has shifted to phonics and decoding) and ‘reading to learn’ (for some purposes, abbreviated to ‘critical thought'(CILIP 2016)) has been directly witnessed and practised by me and my colleagues for at least 5 years (I started in 2014), as part of the Early Action for Success (EAfS) funding program.

This program, in phase 1, poured money into (and continues to do so to some degree) several things like ‘Instructional Leader’ Deputy Principal level positions and ‘mentoring’ time off class, and a large portion of the money has gone towards training teachers in Targeted Early Numeracy (TEN) the ‘Language Learning & Literacy in the Early Years‘ (L3) narrow pedagogies for teaching kindergarten to year 2 students foundational literacy and numeracy skills.

- [Sidebar 1: Originally, the TEN program was, in my opinion, almost completely a spin off of the Count Me in Too (CMIT) program (in which I am trained) and Developing Efficient Numeracy Strategies (DENS), using the Schedule for Early Numeracy Assessment (SENA) 1 or 2. Once trained in TEN, teachers, including myself, utilised CMIT, DENS and SENA to effectively teach the TEN math group games and lessons. Similarly, the L3 program is a spin off of Reading Recovery, linked to Best Start and focussed on kindergarten children (Howell & Neilson 2015).

- Later, L3 teacher training was revised to suite ‘stage 1’ or year 1 & 2 students (which is where I joined the training). Currently, the EAfS program is in ‘Phase 2’ and has embraced micro-level data collection and the new National Learning Progressions …I am being critical here about L3 but not without foundation (Howell & Neilson 2015 p.8).

- And don’t even get me started on the fact that the (now defunct) NSW Literacy Continuum provided for EAfS schools meant that we didn’t even crack open the NSW English Syllabus all year-much less the National Curriculum–we simply taught to and reported on the NSW Literacy and Numeracy continuums! Roar! Outrage! Sirens! Remind anyone of the teaching to the test arguments against NAPLAN? Well hello new Learning Progressions, which have replaced the previous continuums…but I digress…]

What all of this means to me at the moment, in terms of teaching Information Literacy / ‘Reading to learn’, is that, in my current context, half of any given school is focussed on ‘Learning to read’/decoding using L3 guided reading groups, using decodable/phonics/guided readers, teaching students ‘how to read’/decoding without any thought into teaching students ‘reading to learn’/critical thought.

In fact, until a student reaches a particular level of knowing ‘how to read’ (measured in our schools as reading a PM Reader level of 15, based on a 95% success benchmark or ‘running record’ of their reading of a PM Reader that they’ve read at least once before) they may then begin learning skills of ‘reading to learn’/critical thought. For some students, particularly in schools in low Socio Economic Status areas (who, coincidentally, have low NAPLAN results that qualify them for EAfS funding) they don’t reach the PM Reader level of 15 until they are 8 or 9 years old (year 3 or 4) and thus, by that point, reading (so purely focussed on ‘how’ rather ‘why’) has lost all value.

Teach Information Literacy From the Start: What I propose is to teach students, regardless of their age or decoding ability to think critically about texts, using quality texts. It is very difficult to think critically about a (commonly fiction) text that is lacking depth like the little decoding readers that are all the rage at the moment (Adoniou, Cambourne & Ewing 2018). And there is an aspect of L3 that I thought did this particularly well, called ‘Initial, Modelled and Shared readings (IMS),’ However, I was the only teacher at one school who was making time for it amongst the time-heavy requirements of ‘guided reading groups’/how to read lessons. Let’s let that sink in for a moment: nobody had time for information literacy because teaching students how to decode boring levelled readers was taking up all of their time.

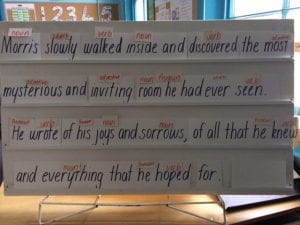

Information Literacy is teaching how to think critically and this is a key part of comprehension and reading for enjoyment. In L3 IMS for stage 1 students (the kindergarten version do something similar but not to the same degree and they call it ‘Reading to’ or similar), is not exclusively the rights of L3 (see this link for further reading) and so I will go into how to run the IMS lessons and how they relate to Information Literacy and a year one (age 6-7) classroom:

- Quality texts: First, the teacher first picks a quality book like The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr Morris Lessmore (2012) by W.E. Joyce. (This was also adapted as an award winning short film (Joyce 2011)- which I just watched for the 20th time and was reduced to tears AGAIN, because I just realised the importance of Information literacy and Teacher Librarians! If you watch it, try to think of the grey people are ‘learning to read’ and the colourful ones are ‘reading to learn’).

- In the world of the story: The teacher reads the book and nobody (including the teacher is allowed to comment).

- Quality Talk Question Prompts: The teacher critically analyses the book and creates a list of possible ‘critical thought’ questions that will be expected from the students in the third reading of the book and has those ready as a reference for the second reading of the text to the students. (For an example of this, see one of my teacher prompt sheets.)

- Modelled reading(s):The teacher reads the book aloud again, possibly even a third time to the students (who are not allowed to comment) but this time the teacher can either explain the meta-language or ‘difficult’ words in the text and then model thinking critically about the book with thoughts based on the prepared list of questions (without actually saying those questions out loud).

- Shared reading: The teacher reads the book a final time and then releases the students to comment freely about the text in a round table / dinner scenario. For younger students, I use a behaviour management / talking technique of a smiley ball that gets passed to those who want to speak and if you have a turn speaking you put a popsicle stick in front of you. If you don’t have a turn speaking about the text, I can see clearly and offer prompts based on my prepared question sheet to help reluctant students.

- Writing: I like to link this to writing lessons, sometimes filming the students

My AL Sentence Board for the Fantastic Flying Books of Mr Morris Lessmore and typing their discussions (or using my Accelerated Literacy sentence board to work on writing conventions), so that they can use what they said about the text in their writing but this is just something that I do and not really related to IMS reading/L3.

So what this all means for me in practice as a TL, is that I need to continue to read to my students and continue to utilise information literacy / critical thought strategies (CILIP 2016) that are proven to improve literacy outcomes for students (regardless of their reading ‘levels’), including aspects of L3 and aspects of Accelerated Literacy because student access to quality (fiction and non-fiction) texts and the ability to practice Information Literacy skills is a key component to learning how to read AND reading to learn.

Next post: Information Literacy for reading to learn and inquiry teaching models…I promise…

References

Adoniou, M, Cambourne, B. & Ewing R. (2018). What are decodable readers and do they work? Retrieved from: https://theconversation.com/what-are-decodable-readers-and-do-they-work-106067

CILIP Information Literacy Group. (2016). Information literacy definitions.

Howell & Neilson (2015). A critique of the L3 early years literacy program. Learning Difficulties Australia, Volume 47(2). pp.7-pp.12. Retrieved from https://www.ldaustralia.org/client/documents/Bulletin%20Winter%202015.pdf

Joyce, W. E. (2012). The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr Morris Lessmore. London: Simon & Schuster.

Joyce, W. E. [Screen name] (2011, January 30). The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr Morris Lessmore. [Video File]. Retrieved from: https://youtu.be/Ad3CMri3hOs

Robb, L. (2011). The myth of learn to read/read to learn. Scholastic Instructor. Retrieved from http://www.scholastic.com/teachers/article/myth-learn-readread-learn

The New Paradigm Part 2 of 2

[ETL401 Module 4]

The New Paradigm: Let’s do both inquiry based learning and outcomes

In the previous post, I discussed collaboration and the steps that I think might be needed to get to a point where I can collaborate with the majority of teachers.

I’ve looked at the research and looked at the *information literacy inquiry models (particularly those more suited to primary and infants classes, such as Big6 and Super3) and okay, I’m in. Where do I sign?

*References in support of Inquiry based teaching and learning:

Bonanno, K. (2015). F-10 Inquiry skills scope and sequence and F-10 core skills and tools. Eduwebinar Pty Ltd, Zillmere, Queensland. Retrieved from: https://s2.amazonaws.com/scope-sequence/Bonanno-curriculum_mapping_v1.pdf

FitzGerald, L (2015) Guided Inquiry in practice, Scan 34/4,16-27

Kuhlthau, C., Maniotes, L. & Caspari, A. (2015) GI: Learning in the 21st century, 2nd edition. Santa Barbara, California: Libraries Unlimited.

Global Education Leadership Programme (GELP, 2011). We wanted to talk about 21st Century education. Retrieved from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nA1Aqp0sPQo

O’Connell, J. (2012). So you think they can learn? Scan, 31, May, 5-11

The New Paradigm Part 1 of 2

(Reflection ETL401 Module 4 – The Teacher Librarian and the Curriculum)

(RSA Animate 2008) This is a very powerful video that offers a dichotomous view of an ‘education paradigm’.

Throwing the baby out with the bath water: While I agree that there has been (or in some cases, needs to be) a shift in the Australian education system, I am hesitant to throw out the baby with the bath water and dispose of outcomes. I have had great success with my students by utilising the NSW syllabus document outcomes and indicators. These have been regularly updated and rearranged over the years and each update, in my opinion, has improved the approach.

Similarly, so have approaches such as ‘play based learning’ or the ‘Reggio Emilia Approach’ / the environment as the ‘third teacher’ (Wein 2015), integrated units such as COGS and inquiry based learning (IBL) such as The Big6 or the Super3 / project based learning (PBL) models evolved over time and have been accepted and used by teachers to varying degrees and with varying degrees of success.

A Breath of Fresh Air: Anyone in the education system for more than 5 years will have seen enough new ideas blow in to the educational sphere to know that they generally blow straight back out to make room for the next big breeze, and leave very little in their wake in terms of real change.

I don’t think this ‘New Paradigm’ is a situation of ‘outcomes based learning’ vs ‘inquiry based  learning.’ I don’t think the two need to be pitted against each other in an argument reminiscent of the recent arguments about how to teach literacy as seen in media and other outlets, for example as per this 2017 blog post by Eleanor Heaton about phonics versus the whole language approach.

learning.’ I don’t think the two need to be pitted against each other in an argument reminiscent of the recent arguments about how to teach literacy as seen in media and other outlets, for example as per this 2017 blog post by Eleanor Heaton about phonics versus the whole language approach.

I see no reason why we can’t have both and simply be more flexible in the application of outcomes to meet real individual student needs.

The real issues with outcome based teaching are based in 1. a lack of authentic growth mindset (Dweck 2006) in adults and students – an inability to see mistakes as part of learning, 2. the social debate regarding reporting to parents and telling the students themselves or their parents that their child has or has not met stage outcomes based on a ‘letter’ mark or tick in a box. Far better, according to Hattie & Peddie (2003), for the system to simply say, ‘this is what sorts of things you/your child can do well, these are things that they are still learning or here are the learning goals for the future.’ It isn’t the outcomes at fault, it is how we’ve applied them to our practice as educators.

[Sidebar 1: To this end, I am extremely interested in the Quality Teaching Framework to improve the structure of lesson delivery (if this is done through inquiry based teaching then so be it) and reading more about ability/interest/friendship grouping of students as opposed to age/year/stage grouping of students.]

[Sidebar 1: To this end, I am extremely interested in the Quality Teaching Framework to improve the structure of lesson delivery (if this is done through inquiry based teaching then so be it) and reading more about ability/interest/friendship grouping of students as opposed to age/year/stage grouping of students.]

[Sidebar 2: If you think Outcome based teaching is holding students back, don’t even get me started on the ‘Learning Progressions,’ ‘NAPLAN’ and the ‘Our Schools’ Website / league tables which have resulted in ‘teaching to the test’ and ‘school shopping.’ Gah.]

[Sidebar 3: If outcome models are so flawed and inquiry models are so perfect, why aren’t universities scrapping outcome based marking criteria and using inquiry models?]

Making assumptions about students: How students find information and their level of ability, particularly when it comes to electronic resources varies widely – much more so than adults realise and according to Coombes, “The basic premise of the Net Generation theory, that familiarity with technology equates with efficient and effective use and these achievements are only applicable to a specific group because they have grown up with technology, is flawed” (Coombes 2009, pp.32).

Technology is a tool, rather than a solution (Coombes 2009). Society has a new ‘digital age’ environment in which we live and we are expecting students to learn how to navigate it simply by being born amongst it. We have a new set of digital expectations in our society but have neglected to update our education system of our students to enable them to meet those expectations.

Information Search Process (ISP) skills / information literacy: Being able to recognise functions of a digital device does not automatically mean that students are able to access, process and absorb information on that they come across on said device (Coombes 2009). Students are overly reliant on the internet, have limited ability to search effectively, and are rarely able to critically evaluate information that they find (Coombes 2009).

The Role of Teacher Librarians (et al.): Educators have responsibility to lift their game when it comes to teaching students information literacy / searching skills such as collecting, managing and evaluating information (particularly when they believe the first thing that appears in their search is the most relevant or most accurate when in fact the first thing that comes up is based on their prior searches and the search engine’s popularity algorithms), finding the information again at a later date, and storing information for future use (Combes, 2007b in Coombes 2009).

Evidence and Assessment within the library: I like the list of ideas in ETL401 Module 3 (based on Valenza 2015) for evidence that the library program is of benefit to the school teaching and learning programs and curriculum. However, I am wary of introducing something that is trivial or that will not stand the test of time or that might sit in a filing cabinet – lost and forgotten.

For that reason, I will use the Quality Teaching Framework and the subsequent evaluation sheet (that I modified on GoogleDocs) to evaluate my lessons or units of work professionally, and will also use the (yet to be created) school library website or more private/access restricted photo/video-based programs (where accepted by the school) for evidence of student engagement or achievement such as ClassDojo, Seesaw or ClassCraft. The benefit of these applications is that they are also able to be used by students themselves, with any device (at home or at school).

I’m looking at you, teachers who profess to be techno-phobes! As Coombes’ 2009 work was written 10 years ago, and research within her article is based on the 10 to ‘teen’ age range, most of the students in her focus are now adults and quite possibly, teachers themselves. Those who are from current and previous generations, as educators, need to be aware of our own gaps in information literacy so that we can stop the cycle of poor information seeking skills!

The Blame Game: What I’ve also seen in education, in varying degrees based on context, is a lack of personal and professional reflection. A lack of ‘mindfulness’ and being in the moment. A wish for the utopian environment and an unrealistic desire for perfect students who fit into a mould and live up to unrealistic expectations and students who are compliant rather than collaborative (Goss & Sonnemann 2017).

This results in a filtering down of ‘blame’ for the poor foundational (primarily literacy and numeracy) skills that students have when they arrive into high school. The high school teachers blame the stage 3 teachers. The stage 3  teachers blame the stage 2 teachers. The stage 2 teachers blame the stage 1 teachers. The stage 1 teachers blame the kindergarten/prep teachers. The kindy/prep teachers blame the preschools. (And everybody blames the RFF teachers and the parents and finally, the students themselves).

teachers blame the stage 2 teachers. The stage 2 teachers blame the stage 1 teachers. The stage 1 teachers blame the kindergarten/prep teachers. The kindy/prep teachers blame the preschools. (And everybody blames the RFF teachers and the parents and finally, the students themselves).

What I’d like to see is every person involved in education taking a look in the mirror and reflecting daily on their pedagogical practice. What I’d like to see is everyone practising mindfulness–thoughtfully doing what they can with the students and contexts that they have in the moment in time in which they are living, and authentic growth mindset–appreciating that mistakes are part of learning.

References:

Combes, B. (2009). Generation Y: Are they really digital natives or more like digital refugees? Synergy, 7(1), 31-40

Dweck, C. (2016). What having a “growth mindset” actually means. Harvard Business Review, 13, 213-226.

Goss, P. & Sonnemann, J. (2017). Engaging Students – Creating classrooms that improve learning. Retrieved from: https://grattan.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Engaging-students-creating-classrooms-that-improve-learning.pdf

Hattie, J., & Peddie, R. (2003). School reports: “Praising with faint damns.” Journal issue, 3.

RSA Animate – Robinson, K. (2008). Changing educational paradigms. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zDZFcDGpL4U#aid=P8wNMEma2ng

Valenza, J. (2015). Evolving with evidence: Leveraging new tools for EBP. Knowledge Quest. 43/3, 36-43

Wien, C. A. (2015). Emergent curriculum in the primary classroom: Interpreting the Reggio Emilia approach in schools. Teachers College Press.