I think a key to mention that ETL505 is different to ETL503 (Resourcing the curriculum) in that ETL503 is about providing quality resources but ETL505 is about “organising resources to facilitate effective access” (Hider, 2018, p.xv). Organising is the key word! So, now  I’m thinking, as per Hider (2018, p. 17), should the name of this class be changed to Information Organisation? (Just kidding). However, more seriously, by chapter 2 I was starting to get very annoyed by the amount of end of sentence prepositions used by Hider (e.g. ‘looking for’ should read simply as ‘looking’ or ‘for which they are looking.’ It is a minor detail I know, but compounded by at least 8 instances in chapter 2, I began to wonder about the quality of the editor).

I’m thinking, as per Hider (2018, p. 17), should the name of this class be changed to Information Organisation? (Just kidding). However, more seriously, by chapter 2 I was starting to get very annoyed by the amount of end of sentence prepositions used by Hider (e.g. ‘looking for’ should read simply as ‘looking’ or ‘for which they are looking.’ It is a minor detail I know, but compounded by at least 8 instances in chapter 2, I began to wonder about the quality of the editor).

What follows are my notes about the readings of Hider (2018) from the introductions and Chapters 1, 2 & 4:

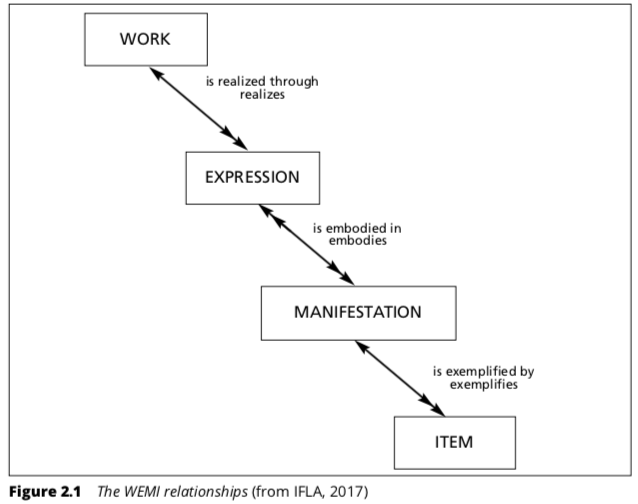

FRBR

Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records or (FRBR) is “a conceptual model of the ‘bibliographic universe’ involving 4 different ‘levels’ of information resource, originally set out in a report published by the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA)” in 1998 and revised in 2017 in IFLA’s Library Reference Model: a conceptual model for bibliographic information (Hider, 2018, p.25).

FRBR has 4 ‘entities,’ called: ‘works, expressions, manifestations and items,’ which are abbreviated ‘WEMI,’ which is shown by Hider in this Figure 2.1:

As well as in this circle chart by Lorenz (2012):

![Lorenz, A. (2012). [Screen shot]](https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/croe/files/2020/08/Screen-Shot-2020-08-05-at-4.25.35-pm.png)

“The point is that different characteristics or attributes of items, manifestations, expressions and works are likely to be important when people think about them for the purposes of finding, identifying, selecting, obtaining and exploring them” (Hider, 2018, p.27).

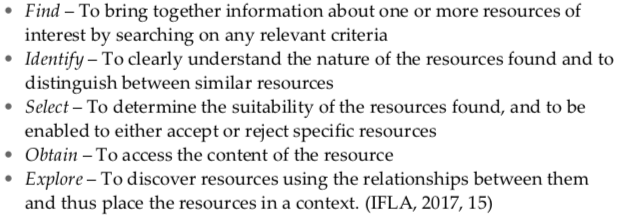

It is a good point in Hider (2018, p.xiii) that, when trying to find, identify, select, obtain, (or access) resources (the FRBR), users can be lost, overwhelmed by choices and simply unable to choose. The resulting poor access to information, (see also my previous blog posts regarding filter failure and filter bubble) and being completely in the dark about quality information are problems that can all be solved by effective resource curation and description / access.

Interestingly, ‘bibliographic’ is defined as ‘book description.’ but as the definition of ‘book’ has widened, so too has the term ‘bibliographic’ (Hider, 2018, p.16). This is also important to note when using the term ‘bibliography.’

Information Resource Descriptions

Descriptions should different aspects of things that they are describing in either elements of: content, carrier, or both content and carrier (Hider, 2018, p.4). ‘Cataloguing’ or ‘indexing’ are often referred to as information, intellectual or knowledge organisation of resources (Hider, 2018, p.13). These are represented by their physical location, but also through their description and the comparison between various resources. In fact, the core of organisation lies in the relationships, commonalities and differences between resources (Hider, 2018, p.40).

The more resources a setting has, the more difficult it is to locate a resource based on its location, so an adequate and ‘representative’ (p.33) resource description (such as an catalogues, indexes, search engines, etc), and effective resource labels (a form of metadata) are key to locating the resource. Particularly, indexes are a vital tool for organising resources, as they are representations of the resources arranged in a user-friendly way (Hider, 2018, p.14-15).

NOTE: Search engines, linked data, data mining and granularity are considered ‘indexing content’ rather than ‘indexing of metadata’ and are part of a seperate field from information science called ‘information retrieval’ (Hider, 2018, p.18) because, in Hider’s view, search engines do not help with the formulation of search queries. However, the modern Web2.0 search engine(s) do have some artificial intelligence or ‘semantic web’ (Hider, 2018, p.19) capabilities, such as the ability to use individual online footprints to narrow (and possibly limit) search results.

“Information resource description is inevitably biased: it is influenced by the motives, situation, limitations and world-view of its creator” (Hider, 2018, p.23).

In terms of FRBR, and resource descriptions, and the resource seeking process that occurs inside the users’ heads, users may also check the ‘relevance criteria’ of the resource based on its content summary, provenance, quality, currency/date, quantity of text, or format and the ‘relevance rankings’ of information retrieval systems, such as those used by the semantic web 2.0, which play a large part in the selection of resources by users (Hider, 2018, p.35-38).

Metadata

Metadata, according to Hider (2018) is an “information ecology” (p.12) “providing an overview of both the process and the product” of organising resources (p.xv) and “information resource description” (p.4) including both the “carrier” (format) and the “content” (information) of the resource (p.5). I interpret that to mean that metadata is an overview of how a resource was created, is delivered and information describing its content.

There are 4 areas of importance with metadata: elements, values, format and transmission (Hider, 2018, p.6-10).

1. Elements or data ‘fields,’ provide the structure of the metadata and are infinite, however it is important to narrow them down to what will be of value to the user, e.g. a resource’s title. The elements are the ‘building blocks’ of metadata and each element describes an ‘attribute’ of the resource, such as its identifier/number, name/title, creator/author/corporation, subject, etc. (Hider, 2018, p.23, 30, 32, 33).

NOTE: Systematic (numerical) identifiers are most commonly known as ISBN’s (international standard book numbers), ISSN (international standard serial numbers), ISMN (international standard music numbers) and DOI’s (digital object identifiers), and the lesser known ISTC (international standard text code), and ISAN (international standard audiovisual number) to name a few (Hider, 2018, p.34).

2. Values, or fundamental content of the metadata are also infinite but often have the greatest impact on the quality of the metadata and are key to a user utilising the description in order to locate a resource (Hider, 2018, p.28). (See more information in Hider, 2018 chapter 5).

3. The method by which the values are encoded or recorded is known as the format, which needs to be compatible with the information retrieval system being used by a setting (note below); and

4. The transmission of the metadata is the protocol used to input the metadata into the information retrieval system, so that the metadata is accessible to the users.

This image found in Hider (2018, p. 7) helps explain the 4 areas of metadata:

There are also the 6 purposes of metadata provided by Hayes’ ‘6 point model’ (in Hider, 2018, p.5): 1. resource identifying and describing, 2. information retrieving, 3. information resource managing, 4. intellectual property right managing, 5. e-commerce/e-government support, and 6. information governing. If we take into account that there are 3 types of metadata: administrative, structural and accessible information resource descriptions, accessible descriptions link to 1. and 2. in Hayes’ model (in Hider, 2018, p.5) and these best correlate with finding, identifying, selecting, obtaining and exploring resources.

Finally, metadata must be continually evaluated for quality control and ongoing growth purposes. We must ask ourselves: 1. Is the metadata from an external source in the right format for our information retrieval system? 2. Does it need improving or editing based on our context (users, systems, costs, or search contexts)? 3. Will it withstand constant technology advances? 4. Is it standardised enough that it might be shared in a (global) network? (Hider, 2018, p10-11). 5. Who are our users, both end-users and intermediary and what are their information needs, knowledge and behaviours? 6. What metadata should be selected to help users to access the information they are seeking? (Hider, 2018, p.24). 7. What methods are we using to analyse our users’ search queries? (Hider, 2018, p.33).

This concept of metadata is interesting to me as a teacher as I have read recently that making students aware of the complex process of writing is key to their success as writers – rather than the actual content of the writing (including punctuation, grammar, spelling or handwriting) itself. Cataloguing / describing resources effectively is not only a means for users to access the resource but also to understand the resource itself at a deeper level. [In fact, one could say that the metadata itself is an information resource!]

This concept of metadata is interesting to me as a teacher as I have read recently that making students aware of the complex process of writing is key to their success as writers – rather than the actual content of the writing (including punctuation, grammar, spelling or handwriting) itself. Cataloguing / describing resources effectively is not only a means for users to access the resource but also to understand the resource itself at a deeper level. [In fact, one could say that the metadata itself is an information resource!]

Information Retrieval Systems / SCIS / Oliver / RDA

Information retrieval systems are designed to improve access to collections of information resources and may influence the nature and structure of the metadata (Hider, 2018, p.6).

Information retrieval systems are a means of ‘cataloguing,’ providing ‘bibliographic data,’ ‘indexing,’ ‘tagging,’ ‘archival description,’ and in some cases, ‘museum documentation’ (Hider, 2018, p.6).

Commonly used in Australia are the cataloguing information retrieval systems: SCIS and Oliver, and here is an image showing how SCIS use various standards in the process of creating their cataloging metadata:

However, our first assessment in ‘Describing and Analysing Educational Resources’ requires us to use the library cataloguing code: Resource Description and Access (RDA) mentioned by Hider (2018, p.xv).

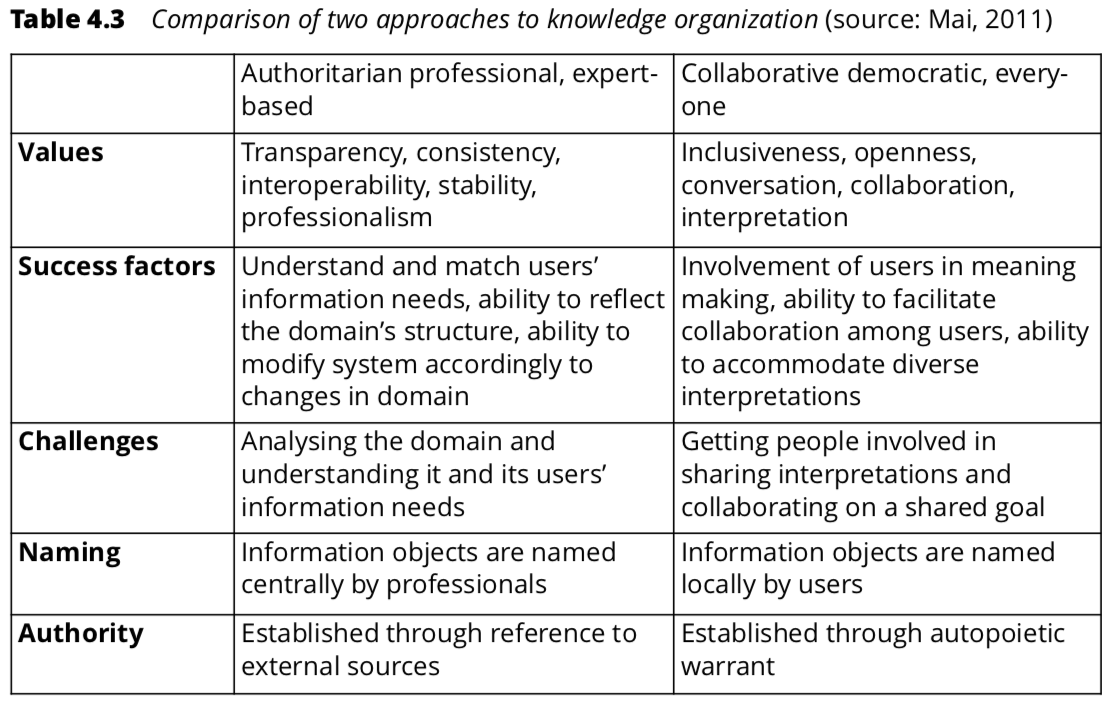

Who is responsible?

Publishers, authors, creators, information retrieval system operators, teacher librarians/information specialists/metadata librarians, archivists, records managers, museum curators, information architects and the general public ‘end users’ can all be responsible (however uncontrolled, inaccurate, informal and inconsistent) for creating and disseminating metadata through the use of publishing standards, the requirement for authors to write abstracts and keywords for their resources, as well as through desktop publishing computers, social media applications and the internet which have made it far easier for end users to create (tag, meta-tag, label, #tag, hyperlink or embed) and disseminate metadata and information resources (Hider, 2018, p.74-86). The relative benefits of formal vs informal knowledge organisation is best represented by this Table 4.3 by Hider (2018, p. 87):

Information specialists / teacher librarians need to establish ‘communities of practice’ (Hider, 2018, p.77; See also my previous blog posts on this topic). They must be able to understand the foundations of metadata in order to fulfil the roles and responsibilities of directing and guiding students / users towards quality information resources and to best be able to access the resource though effective cataloging and to access the content within the resource through effective information literacy skills (Hider, 2018, p.75-77; See also my other posts on TL roles and responsibilities).

Note: Computers/semantic web/applications can also do indexing and metadata of sorts, and this is improving rapidly, however computer programs still require human input and regulation in order to present metadata effectively (Hider, 2018, p.88-89).

Genrefication – Do fiction books inform?

I like it that Hider (2018, p.1-2) points out that, although they will always have a primary purpose, resources can have different purposes. I have been sorting my personal library after our house move and found it challenging whether to put self-help style fiction children’s books in the fiction picture book section or in the teaching key learning area (KLA) ‘genre’ section of my library. For example, the picture book ‘I like myself’ is used in stage 1 PDHPE (health) lessons. Do I put it in that genre or do I keep it with straight fiction picture books, organised by author nam e? I chose genre–after all, it isn’t by a well known author and I need to be able to access it quickly. It’s primary purpose is to inform, rather than entertain, yet I fully support the argument that a good number of children’s fictional picture books have the primary purpose of informing their readers. (Genrefication…see the link for an idea for further reading).

e? I chose genre–after all, it isn’t by a well known author and I need to be able to access it quickly. It’s primary purpose is to inform, rather than entertain, yet I fully support the argument that a good number of children’s fictional picture books have the primary purpose of informing their readers. (Genrefication…see the link for an idea for further reading).

References

Chadwick, B. (September 2017). SCIS: Bibliographic data for education. [Interact2 Recorded Adobe Connect Webinar; Screen shot of protocols]. Education Services Australia.

Hider, P. (2018). Information resource description: Creating and managing metadata (2nd ed.). London: Facet. [Introduction(s) & Chapters 1, 2, 4]

Lorenz, A. [Andrea Lorenz]. (2012, August 9). FRBR simplified. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LPBpP0wbWTg

Further reading

Chadwick, B (2015). SCIS is more. Connections, 2015(92), 12. https://www.scisdata.com/connections/issue-92/scis-is-more/

Schools Catalogue Information Service (2020). Schools Catalogue Information Service. https://www.scisdata.com

Schools Catalogue Information Service (2020). SCIS catalogue. https://myscisdata.com/discover (accessible once you have logged in to SCISData)

Schools Catalogue Information Service (2019). SCIS standards for cataloguing and data entry. https://www.scisdata.com/media/1738/scis-standards-for-cataloguing-and-data-entry.pdf

Schools Catalogue Information Service (2020). SCIS subject headings. https://my.scisdata.com/standards (accessible once you have logged in to SCISData)