This subject has given me the opportunity to think deeply about my practice as a teacher librarian. Teaching throughout the pandemic, has been a matter of survival for many teachers, removing opportunities for exciting collaborative work. I have high hopes for 2023 and this subject has given me a new meaning for ‘third space’; a space for students to consider and create their own view on what they are presented with by their teachers in the classroom (Korodaj, 2019). I have a kaleidoscope of new ideas for using fiction as stimuli for cross-curricular thinking, bringing together themes connecting curriculum subject divides (Waugh et al., 2016).

I haven’t used the third space enough in the past, taking advantage of students view. There isn’t one right answer when interpreting a fiction text. The polysemic nature of text to include intertextuality and “gap” presents learning opportunities for discussing perspectives, adapting to reader ability (Evans, 1998). Students need space to build on their own background information, previous experience and socio-cultural issues that they bring to the text. These interactions make fiction come alive.

I’m looking forward to creating a safe space, where students are more willing to explore new and challenging ideas where they feel safe taking risks (Pierce & Gilles, 2021). I’m excited to introduce yarning circles, giving students a personal connection to Aboriginal culture. I want to persevere building local connections as well, benefiting the entire school community as through knowing, being and doing Indigenous ways, students build confidence and understanding about the world learning from Indigenous footprints (David-Warra et al., 2011).

I’ve grappled with a few issues throughout this subject. Fiction themes can be potentially triggering due to life experiences or trauma. In the school I work in, students experiences can involve domestic violence, resistance to LGBTQ+, war with neighbouring countries in their homeland causing extreme difficulties with parents/carers and fiction. I have a heightened awareness now, realising the reader response arises from their lived experience, perspective. I’ve also struggled with the increasing trend of concerns with author authenticity and accuracy (Short, 2018). Hodgson (2022) pointed to an alternative perspective; Heiss stating that writers are writing about people and they must find the balance between including Indigenous characters and avoiding tokenism. Strategies include reading widely, researching thoroughly, open communication and respecting diversity (Case, 2014).

I continue to struggle with deciding within the library program the weighting of meeting outcomes and reading for pleasure, potentially halting the development of lifelong recreational readers (Gallagher, 2009). I am going to encourage free voluntary reading and sustained silent reading programs (Krashen, 1997) to colleagues, pushing the influence beyond the walls of the library into the class teacher’s domain. I have underestimated the positive effects classroom libraries have on reading growth and achievement (Lindsay, 2010). McDonald (2022) led me to consider student choice, giving me a solution to an issue I’ve struggled with for some time. By asking students who repeatedly experience difficulty returning their books to select books for their classroom library, it enables them to read their favourite book at school, helping to reduce feelings of embarrassment potentially arising from a difficult home life.

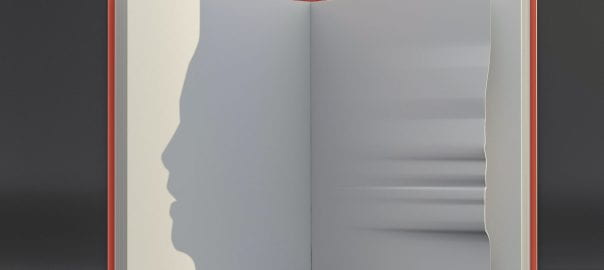

I reflected on whether the collection in my library truly represented the diversity within the school community and it was a reminder to continually question our own limited lenses. Children’s literature should provide the opportunity for readers to look in a mirror and see reflections of themselves and their lives; look through a window to gain insights about the broader world; and be a sliding door to gain entry to the real or imagined world created by the author (Bishop, 1990).

Teacher librarians can model ways for students and teachers to challenge conventions and to seek literature that provides multidimensional, complex narratives of all people (Mackey, 2013). I’ve discovered the Diverse BookFinder (Diverse BookFinder, n.d.), Aboriginal and or Torres Strait Islander Resource (National Centre for Australian Children’s Literature, n.d.-a) and Cultural Diversity Database (National Centre for Australian Children’s Literature, n.d.-b) are excellent resources when evaluating the diversity of the collection.

References

Bishop, R. S. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives, 6(3).

Case, J. (2014, November 4). ‘Getting it Right’: Anita Heiss on Indigenous Characters. The Wheeler Centre. https://www.wheelercentre.com/wlr-articles/221927959a6b/

David-Warra, J., Dooley, K. T., & Exley, B. E. (2011). Reflecting on the ‘Dream Circle’: Urban Indigenous education processes designed for student and community empowerment. QTU Professional Magazine, 26, 19–21.

Diverse BookFinder. (n.d.). Diverse BookFinder | Identify & Explore Multicultural Picture Books. Diverse BookFinder. Retrieved 12 January 2023, from https://diversebookfinder.org/

Evans, J. (1998). Responding to illustrations in picture story books. Reading, 32(2), 27–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9345.00086

Gallagher, K. (2009). Readicide How Schools Are Killing Reading and What You Can Do About It. Stenhouse Publishers.

Hodgson, S. (2022, November 27). Thread: 3.1a Indigenous voices – S-ETL402_202290_W_D … Interact 2. https://interact2.csu.edu.au/webapps/discussionboard/do/message?action=list_messages&course_id=_64656_1&nav=discussion_board_entry&conf_id=_128963_1&forum_id=_297918_1&message_id=_4265078_1

Korodaj, L. (2019). The library as ‘third space’ in your school. Scan, 38(10), 2–9. https://doi.org/10.3316/aeipt.226270

Krashen, S. (1997). Free Voluntary Reading: It Works for First Language, Second Language and Foreign Language Acquisition. 20(3).

Lindsay, J. (2010). Children’s Access to Print Material and Education-Related Outcomes: Findings From a Meta-Analytic Review. Learning Point Associates.

Mackey, M. (2013). The Emergent Reader’s Working Kit of Stereotypes. Children’s Literature in Education, 44(2), 87–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10583-012-9184-1

McDonald, W. (2022, December 22). Thread: 4.1: Strategy to leverage a love of reading [Online discussion comment]. Interact 2. https://interact2.csu.edu.au/webapps/discussionboard/do/message?action=list_messages&course_id=_64656_1&nav=discussion_board_entry&conf_id=_128963_1&forum_id=_297921_1&message_id=_4265019_1

National Centre for Australian Children’s Literature. (n.d.-a). Aboriginal and or Torres Strait Islander Resource. NCACL. Retrieved 12 January 2023, from https://www.ncacl.org.au/atsi-resource/

National Centre for Australian Children’s Literature. (n.d.-b). NCACL Cultural Diversity Database. NCACL. Retrieved 12 January 2023, from https://www.ncacl.org.au/cd-database/

Pierce, K. M., & Gilles, C. (2021). Talking About Books: Scaffolding Deep Discussions. The Reading Teacher, 74(4), 385–393. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1957

Short, K. G. (2018). What’s Trending in Children’s Literature and Why It Matters. Language Arts, 95(5), 287–298.

Waugh, D., Neaum, S., & Waugh, R. (2016). Children’s Literature in Primary Schools [Online discussion comment]. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473984349

Photo by 愚木混株 cdd20 on Unsplash