Part D: Critical Reflection

The subject of Literature in Digital Environments has challenged my thinking about how students engage with digital resources. During the Covid-19 lockdown, libraries had to evolve and connect to their readers in new and innovative ways, which involved interacting online and expanding electronic resource collections (Garner et al., 2021).

Module 1 provided the opportunity to expand thoughts about trends in digital literature. Curtis (2022, July 22) made the point that many teachers continue to evaluate literature based on our preconceived ideology of it being text-based, while digital literature is far beyond this. Similarly, in my first blog post for ETL533 (Foyel, 2022a) it was noted that although digital literature can deepen understanding, careful consideration needs to be made in selecting useful forms of digital literature amongst the vastness of choice (Dobler, 2013).

Interactive eBooks were featured early in my career (Foyel, 2022a), and was also noted (Foyel, 2022b) that digital texts afford new possibilities for reading and engaging with content (Lamb, 2011). McGeehan et al. (2018) entertained the idea that digital texts need to offer readers the opportunity to interact with the text, and educators seeking criteria to select quality digital literature.

Frustration arose in Module 2 when asked to consider the challenges of using digital technology in the classroom. For some teachers, embracing change is the first challenge to overcome (Foyel, 2022c), though this is not my biggest concern. Time and resources to explore new resources is my greatest frustration, where infowhelm is often at the forefront of my overwhelm (Foyel, 2022d).

Assessment 2 allowed time to explore different formats of digital literature. Though the quest to succinctly define what counts as a digital text continued. Wheeler (2022, August 8) aptly pointed out the frustration of defining an eBook vs a book app and Sargeant’s (2015) article helped to put into perspective that an eBook is read, while book apps are used. Undeniably, digital stories are not bound between pages, rather they offer features and experiences that cannot be provided by a print book (Yokota & Teale, 2014).

Furthermore, storytelling has played an important role in history “to share knowledge, wisdom and values” (Malinta & Martin, 2010, p. 3061) and evolving over time into the digital realm (Combes, 2019). Storytelling is constant, though constantly changing. Fisher and Hitchcock (2022, p. 371) defined digital storytelling broadly as “using computer-based tools to tell stories”. Stackhouse (2013) discussed transmedia and the increasing ways to tell digital stories and gain access to others’ stories. Stackhouse (2013) noted that higher levels of engagement can be linked to making decisions within a story.

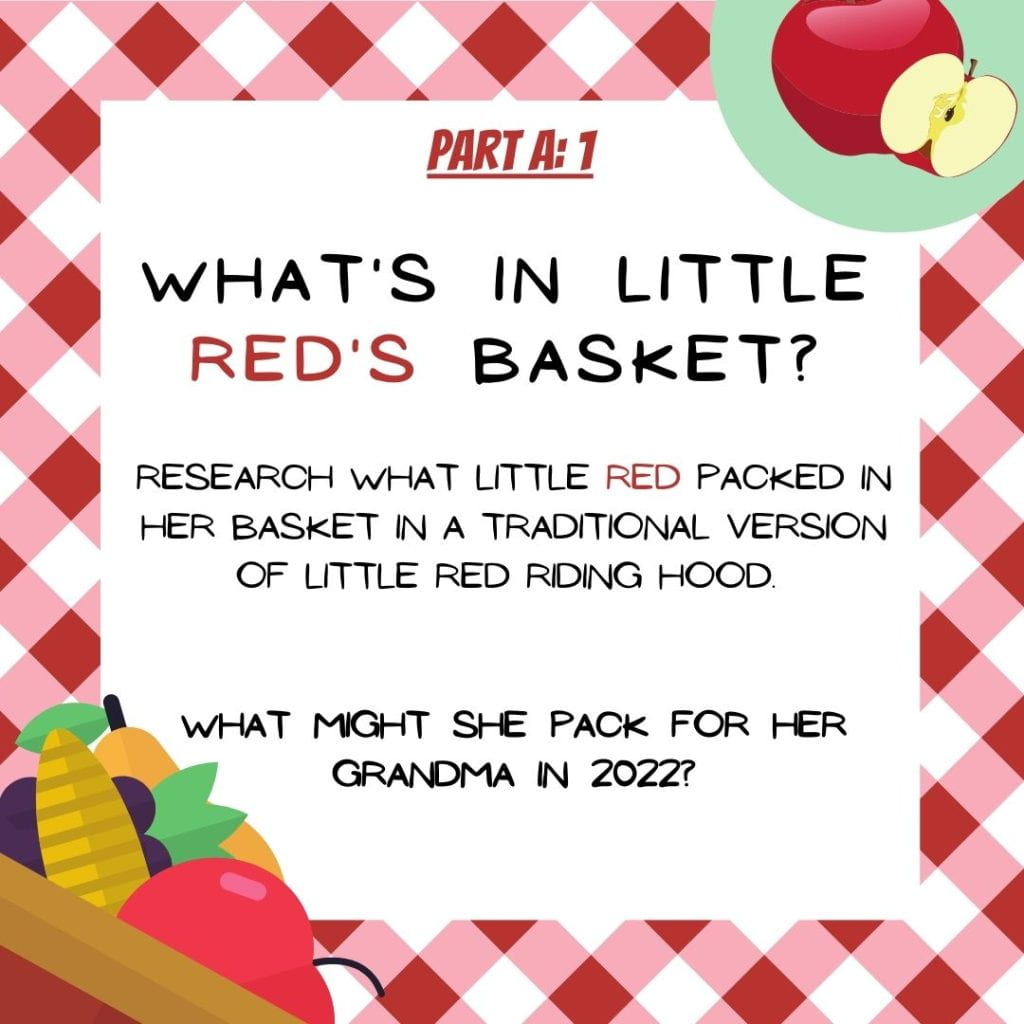

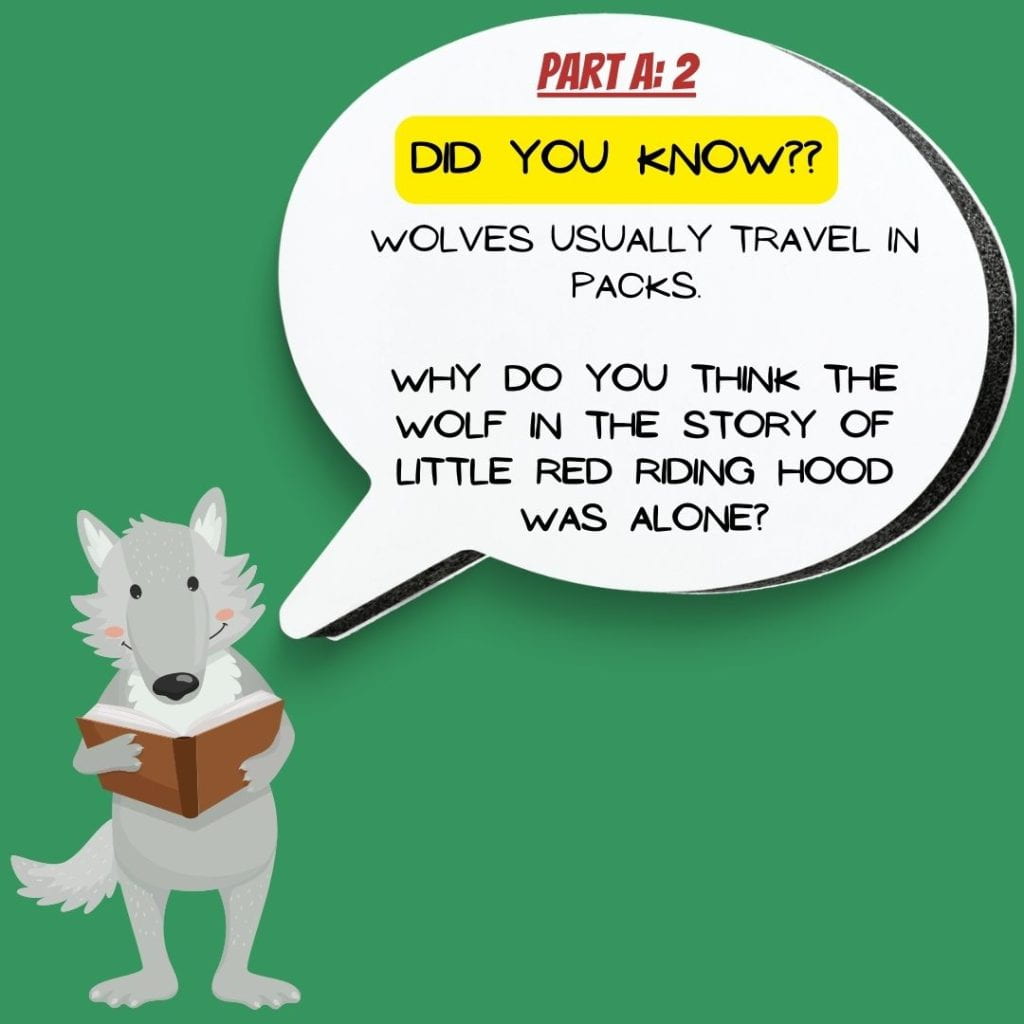

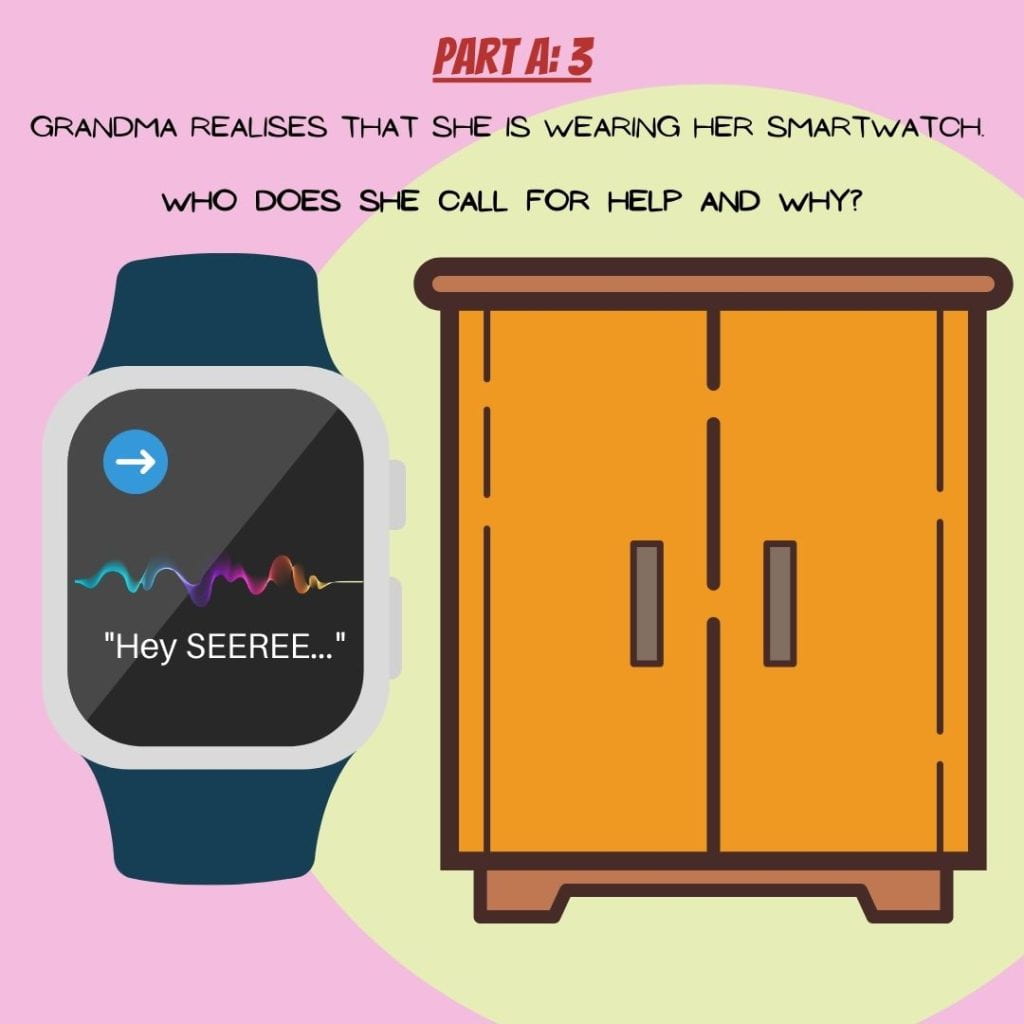

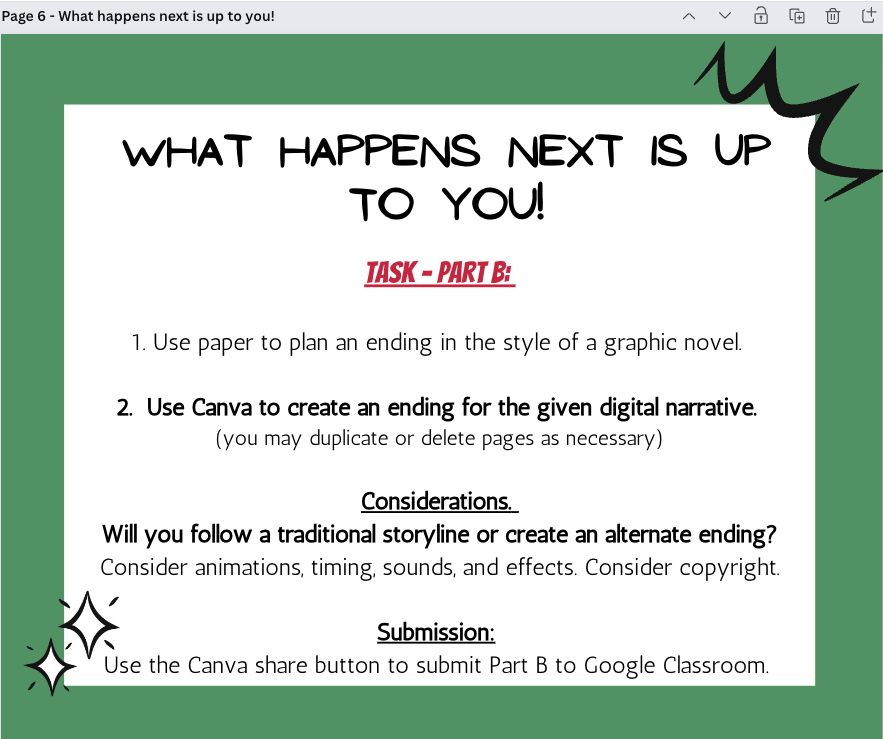

This idea of decision-making in a story initiated my ideas about my own storytelling project. After analysing the reading habits of Stage 3 students, there was an undeniable gravitational pull toward graphic novels. Moorefield-Lang and Gavin (2012) discerned the visual nature of digital graphic novels is preferable to the 21st Century reader. Canva was the creative platform of choice due to personal familiarity and having previously taught Stage 3 to use it. Project decisions were based on promoting maximum engagement while building creativity and digital literacy skills (Fisher & Hitchcock, 2022). With this in mind, a folktale was incorporated as Stage 3 enthusiastically engaged in this writing topic during 2022.

Feedback was gained from road testing the resource with students and peers on my blog post, which was used to refine design choices. Curtis (2022, September 18) suggested adding interactivity elements, such as clicking an image to read a recipe. Interactivity was then included as comprehension tasks. Student feedback also instigated the ‘light bulb’ element to ensure students could locate the comprehension tasks. Facey (2022, August 29) proposed making the resource “real world” for students, this was incorporated into the comprehension tasks, giving the questions a 21st Century feel.

Stage 3 student feedback was valuable, and adjustments were based on this. Some suggested more dialogue was needed and others wanted more coloured images. Additional dialogue was inserted to help students understand the story and the layout was reordered to ensure the story could be followed. Colour vs black and white images represent “good” vs “bad” characters and was not changed. Overall, student feedback was extremely positive, students were engaged and excited to participate further (Foyel, 2022e).

Future developments may include a read-to-me option, to support students of low ability or from non-English speaking backgrounds. Barnett’s (2022, September 16) comment inspired this idea, where she pointed out that research by Yang et al. (2022) suggests “oral development and creativity skills in non-English speakers benefit from constructing meaning through digital storytelling in English” (2022, para. 2).

This subject has inspired creativity and compelled me to consider the vast formats of digital resources in a new way, though continuing to critically analyse them to ensure they are integral to students’ learning and growth as we “cannot predict what the future will hold” (Yokota & Teale, 2014, p. 585).

References (Part D)

Anonymous. (2022). Module 4.1. Understanding the value of digital storytelling. ETL533, Interact 2. https://interact2.csu.edu.au/webapps/blackboard/execute/displayLearningUnit?course_id=_64104_1&content_id=_5128719_1

Barnett, C. (2022, September 16). I have no doubt that your Stage 3 students will be completely absorbed in this unit of work! [Comment on “Digital storytelling proposal]. Mastering Librarianship. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/librarianlouise/2022/08/28/digital-storytelling-proposal/comment-page-1/#comment-13

Combes, B. (2019). Digital Literacy: A New Flavour of Literacy or Something Different?. Synergy, 14(1). https://www.slav.vic.edu.au/index.php/Synergy/article/view/v14120163

Curtis, J. (2022, July 22) If we redefine ‘literature’, do we need to redefine ‘reading’?. [Forum post]. ETL533, Interact 2. https://interact2.csu.edu.au/webapps/discussionboard/do/message?action=list_messages&course_id=_64104_1&nav=discussion_board_entry&conf_id=_128305_1&forum_id=_282785_1&message_id=_4149565_1

Curtis, J. (2022, September 18). Firstly, I wholeheartedly agree with your observation about graphic novels soaring popularity. [Comment on “Digital storytelling proposal]. Mastering Librarianship. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/librarianlouise/2022/08/28/digital-storytelling-proposal/comment-page-1/#comment-14

Dobler, E. (2013). Looking beyond the screen: evaluating the quality of digital books. Reading Today, 30(5), 20 – 21.

Facey, A. (2022, August 29). I love that you are also going to use Canva as a means of producing digital work. [Comment on “Digital storytelling proposal]. Mastering Librarianship. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/librarianlouise/2022/08/28/digital-storytelling-proposal/comment-page-1/#comment-8

Fisher, C. M., & Hitchcock, L. I. (2022). Enhancing Student Learning and Engagement Using Digital Stories. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 42(4), 371–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2022.2113492

Foyel, L. (2022a, July 24). When is a book not a book? Mastering Librarianship. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/librarianlouise/2022/07/24/when-is-a-book-not-a-book/

Foyel, L. (2022b, August 21). Critical reflection of digital literature experiences. Mastering Librarianship. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/librarianlouise/2022/08/21/critical-reflection-of-digital-literature-experiences/

Foyel, L. (2022c, August, 8). 24 years of change. [Forum post]. ETL533, Interact 2. https://interact2.csu.edu.au/webapps/discussionboard/do/message?action=list_messages&course_id=_64104_1&nav=discussion_board_entry&conf_id=_128305_1&forum_id=_282786_1&message_id=_4177475_1

Foyel, L. (2022d, August 13). Consumer challenges. [Forum post]. ETL533, Interact 2. https://interact2.csu.edu.au/webapps/discussionboard/do/message?action=list_messages&course_id=_64104_1&nav=discussion_board_entry&conf_id=_128305_1&forum_id=_282787_1&message_id=_4190067_1

Foyel, L. (2022e, October 2). Creating a digital story – Feedback. [Forum post]. ETL533, Interact 2. https://interact2.csu.edu.au/webapps/discussionboard/do/message?action=list_messages&course_id=_64104_1&nav=discussion_board_entry&conf_id=_128305_1&forum_id=_282779_1&message_id=_4249218_1

Garner, J., Hider, P., Jamali, H. R., Lymn, J., Mansourian, Y., Randell-Moon, H., & Wakeling, S. (2021). “Steady Ships” in the COVID-19 Crisis: Australian Public Library Responses to the Pandemic. Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association, 70(2), 102–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750158.2021.1901329

Lamb, A. (2011). Reading redefined for a transmedia universe. Learning and Leading with Technology, 39(3), 12-17. http://ezproxy.csu.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=67371172&site=ehost-live

Malinta, L. and Martin, C. (2010). Digital storytelling as a web passport to success in the 21st Century. Science Direct. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2(2), 3060-3064. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.465

McGeehan, C., Chambers, S., & Nowakowski, J. (2018). Just because it’s digital, doesn’t mean it’s good: Evaluating digital picture books. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 34(2), 58-70. https://doi.org/10.1080/21532974.2017.139948

Moorefield-Lang, H. and Gavigan, K. (2012) These aren’t your father’s funny papers: The new world of digital graphic novels. Knowledge Quest, 40(3), 30-42. https://web-s-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.csu.edu.au/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=1&sid=283419e7-3319-4e52-9b5a-61c67de16080%40redis

Sargeant, B. (2015, February 6). What is an ebook? What is a book app? And why should we care? An analysis of contemporary digital picture books. Children’s Literature in Education, 46(4), 454-466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10583-015-9243-5

Stackhouse, A. (2013, May 22). Blurring the lines: Storytelling in a digital world. [Video]. TEDx Talks. YouTube. https://youtu.be/9c0bEZS1jC4

Wheeler, A. (2022. August 18). eBook vs book app. [Forum post]. ETL533, Interact 2. https://interact2.csu.edu.au/webapps/discussionboard/do/message?action=list_messages&course_id=_64104_1&nav=discussion_board_entry&conf_id=_128305_1&forum_id=_282788_1&message_id=_4195924_1

Yang, Y. T. C., Chen. Y. C., & Hung, H. T. (2022). Digital storytelling as an interdisciplinary project to improve students’ English speaking and creative thinking. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 35(4), 840-862. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1750431

Yokota, J., & Teale, W. (2014). Picture books and the digital world. The Reading Teacher, 67(8), 577-585. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1262