Context for Digital Storytelling Project

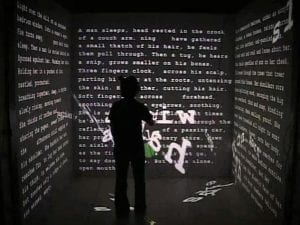

The creation of an interactive version of Edgar Allen Poe’s poem ‘Annabel Lee’ is planned to assist in differentiating the Victorian Curriculum for level 9 English students with Specific Learning Disorders as they move from remote learning to on campus. The secondary school situated in regional Victoria has 200 year nine students enrolled, with approximately 20 students identified as having a diagnosed learning difficulty that impacts their reading. Remote Learning impacted these students significantly in term 3. Curriculum assigned texts that should have been able to be read together as a class were unable to be. As term 4 will see a return to remote learning for week one, having a text that the students can have read to them will hopefully reduce this impact.

In term 4 students in year nine will be studying poetry and in particular works by Poe. This is a follow up from Term 3 when students looked at Poe’s short stories. It was evident during this unit of work that students with Specific Learning Difficulties had trouble comprehending Poe’s original language and struggled to engage with the content. By creating a digital interactive book for the students, it is hoped they will gain a clearer understanding of the writing and therefore be able to participate fully with their peers.

Copyright of the original text was considered before the development of the poem. According to the United States (U.S) Copyright Office “[A]ll works published in the U.S. before January 1, 1923, are in the public domain” (United States Copyright Office, 2011). As Poe wrote this poem in 1849, Annabel Lee is considered to be in the public domain and therefore not subject to copyright (Law, 1922).

Researching an appropriate platform for delivering the interactive story was the next step. Adobe Spark, Loom, Book Creator and Microsoft Sway were considered and tested. Ultimately Microsoft’s Sway application was chosen to present this traditional learning activity redesigned with digital tools. The secondary school where this interactive story will be utilises the entire Microsoft suite of programs. It is an application the students and teachers are familiar with and will not require teaching on how to read this book. Familiarity played a role, as did Sway’s programming features. Sway is a cloud-based, story-telling application that is easier to use than PowerPoint and allows for more narrative devices, hyperlinks and audio features.

The interactive book will break the writing up, using a reading technique called chunking, where larger sections of text are ‘chucked’ to make the text more manageable (Facing History and Ourselves, 2020). This helps to ensure students are not overwhelmed by the number of words as well as make it easier for them to arrange and synthesise information. There will also be the option to have sections of text delivered audibly if required. Research shows that having a text read aloud helps the student develop their information processing skills, their vocabulary and comprehension (Center for Teaching, n.d.). Also included in the interactive book will be hyperlinked to further information to assist comprehension. Links to have definitions and pronunciations along with clarification on meanings of phrases and additional images to aid connection to the setting.

Poe’s original poem has a reading score of 14, making it suitable for 19-20-year-olds—according to the Flesch Kincaid Reading Ease (WebFX, 2020). While some scaffolding will be required for all students to gain comprehension, the reading age of the students with Specific Learning Disorders in level 9 is significantly lower. The cohort includes students diagnosed with Dyslexia, processing difficulties and language disorders. Hazzard (2016) states that being read to increases, the comprehension attained for students. It is anticipated that having the poem read aloud to them as many times as they choose will achieve this comprehension increase.

This interactive story compliments Level 9 of the Victorian Curriculum F-10 for English which includes the descriptor VCELT438. ‘Analyse texts from familiar and unfamiliar contexts, and discuss and evaluate their content and the appeal of an individual author’s literary style (Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority [VCAA], 2020). Students will analyse Poe’s poem Annabel Lee and examine how he used devices such as imagery and symbolism and how that has an effect on audiences today. Another descriptor that will be linked to this unit is VCELA428. Investigate how evaluation can be expressed directly and indirectly using devices, including allusion, evocative vocabulary and metaphor (VCAA, 2020). Students will compare the language used in Annabel Lee to another text that uses evaluative language and how that comparison directs the views of the readers.

References

Center for Teaching. (n.d.). What are the benefits of reading aloud? https://teach.its.uiowa.edu/sites/teach.its.uiowa.edu/files/docs/docs/What_are_the_Benefits_of_Reading_Aloud_ed.pdf

Facing History and Ourselves. (2020). Teaching strategies: Chunking. https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/teaching-strategies/chunking#:~:text=%E2%80%9CChunking%20the%20text%E2%80%9D%20simply%20means,students%20have%20used%20this%20strategy.

Hazzard, K. (2016). The Effects of Read Alouds on Student Comprehension. Education Masters. 351. https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1360&context=education_ETD_masters

Law, R. (1922). A Source for Annabel Lee. The Journal of English and Germanic Philology, 21(2), 341-346. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27702645

United States Copyright Office. (2011). Duration of Copyright. https://www.copyright.gov/circs/circ15a.pdf

WebFX. (2020). Readability test tool. https://www.webfx.com/tools/read-able/flesch-kincaid.html

VCAA. (2020). Level 9, In Victorian Curriculum Foundation-10. https://victoriancurriculum.vcaa.vic.edu.au/level9?layout=1&d=E