The intrinsic need for mankind to document thoughts, experiences and information dates way back to prehistoric times. These have developed over time, from primitive cave drawings through to hieroglyphics and then to forms of written text. With the introduction of technology, the potential to store and present text has grown exponentially. It makes sense then that literature and how we view it, has transitioned into the digital world and therefore transformed the way in which we access and experience information.

Defining Digital Texts

The Australian Curriculum Glossary defines digital texts as audio, visual or multimodal texts produced through digital or electronic technology. They may be interactive and include animations or hyperlinks. A good digital text enhances traditional print text and provides digital affordances in order to provide users with a fully immersive experience that cannot occur between the pages of a book. These texts immerse the reader in a sensory experience that is not the same as purely print literature (Jabr, 2013).

Through exploring a variety of digital texts throughout INF533 course readings and other exploratory research it is evident that there are different levels of immersive experiences, Sadokierski (2013) discusses the digital text as one that allows the reader to encounter audio visual and interactive elements that can’t be experienced through a print text. A good digital text experience encourages readers to enrich their reading experience in order to gain meaning and deepen understandings that may otherwise not be possible in print.

Benefits and Purposes of Digital Literature

The development of digital immersive texts have created opportunities to engage in literature in a manner that, if cleverly presented by an educator, can deepen understanding with opportunities to expand the scope of learning as seen in Blooms Digital Taxonomy. Other benefits are reported in recent literature, ranging from the development of academic skills such as critical thinking, report writing and research skills to digital, oral and written literacies (Ohler 2006).

With technology being embedded in everyday life it seems logical for educators to utilise these intrinsic skills and bring enhanced books into the classroom setting. As stated by Valenza and

Stephens (2012, p. 75) rather than expecting a movement away from books, the reading experience will continue to evolve and advancing technology will become a routine aspect of engaging with literature (Unsworth, 2006, p. 29). It is how this is done that requires careful targeted planning and consideration in line with curriculum outcomes that is important.

Experiencing Reading Digital Texts

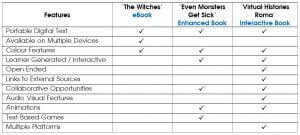

It is important for educators to explore alternatives to traditional print text in order to offer students with targeted, immersive experiences for as stated by Pappas (2019) educators have full control to make sure learners actually learn, remember and engage. All you need is a platform which is designed to do so. However, when exploring a selection of three forms of digital texts it became evident that not all electronic literature offers the same features, therefore external factors need to be considered for use in education settings. These can include cost, compatible devices and user technological abilities. Table 1.1 demonstrates the vast differences experienced through the review process of three forms of ebooks.

Table 1.1

Digital Texts Incorporated into School Environments

Digital storytelling pushes students to create content rather than simply just being a consumer of a text. Hall’s (2102, p.97) statement that even though today’s students are considered to be digital natives they are more so passive consumers rather than literary creators proved to be an important realisation. The ability to immerse, experience, think and question encourages them to demonstrate a higher level of thinking and understanding resulting in outcomes not previously possible with print. Digital storytelling is a powerful tool to incorporate required learning outcomes including technology skills, develop literary skills, build confidence and establish a sense of community and collaboration (Sukovic, 2014, p. 206)

Digital texts in a school environment provides opportunities for educators to rethink learning for a digital age however with new potential and the necessary release of teacher control there is always considerations for why there is a need for change. The SAMR model for technology change provides a scaffolding for educators to determine the benefits for selecting a technology based approach.

Whilst rethinking learning for a digital age can be a daunting concept, it allows us to explore the diversity of possible e-learning experiences today and provides opportunities to analyse learners’ experiences holistically, across the many technologies, an integrated curriculum and through the learning opportunities in which they encounter.

To manage assessment of outcomes in a unit of work with such a divergent and open‐ended nature, it is helpful if digital storytelling activities are framed carefully and explicitly tied to the core content and process goals encompassed in the curriculum (Hofer and Swan 2006). Despite the challenges of change, using digital storytelling in schools is an exciting space as students who display an aptitude for networking, creativity and using digital applications can be uncovered.

References

Andrade, C. Integrating technology in the EFL classroom: Blooms Digital Taxonomy. 2017. Retrieved from https://eltplanning.com/tag/blooms-digital-taxonomy/

Australian Curriculum Glossary Retrieved from https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/languages//Glossary/?term=Digital+texts

Hall, T. (2012). Digital renaissance: The creative potential of narrative technology in education. Creative Education, 3(1), 96-100. Retrieved from http://file.scirp.org/Html/17301.html

Hofer, M. and Swan, K.O. Digital storytelling: Moving from promise to practice. Proceedings of Society for Information Technology and Teacher Education International Conference 2006. Edited by: Crawford, C. pp.679–84. Chesapeake, VA: AACE. [Google Scholar]).

Jabr, F. (2013, April 11). The reading brain in the digital age: The science of paper versus screens. Scientific American. Retrieved fromhttp://www.scientificamerican.com/article/reading-paper-screens/

Kelly. (2016 March 1). The Evolution of Bloom’s Taxonomy. [blog post]. Instructional Design by Kelly. Retrieved from https://instructionaldesignbykelly.wordpress.com/2016/03/01/the-evolution-of-blooms-taxonomy-and-how-it-applies-to-teachers-today/

Morra, S. 2013 8 Steps to Great Digital Storytelling. Edteacher Retrieved from https://edtechteacher.org/8-steps-to-great-digital-storytelling-from-samantha-on-edudemic/

Ohler, J. 2006. The world of digital storytelling. Educational Leadership, 63(4): 44–7. [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]

Pappas, C (March 2019) eBook Release – Interactive Learning Design: Using An Interactive Learning Software To Increase Engagement In eLearning Courses (Web Blog Post) Retrieved from https://elearningindustry.com/interactive-learning-design-software-increase-engagement-free-ebook

Sadokierski, Z. (2013, November 12). What is a book in the digital age? [Web log post]. Retrived from http://theconversation.com/what-is-a-book-in-the-digital-age-19071

Sukovic, S. (2014). iTell: Transliteracy and digital storytelling. Australian Academic & Research Libraries, 45(3), 205–229. doi: 10.1080/00048623.2014.951114

The SAMR Model Retrieved from http://techinfusedlessons.weebly.com/samr-model-for-reflection.html

Unsworth, L. (2006). Learning through web contexts of book-based literary narratives (Ch. 3). In E-literature for children: Enhancing digital literacy learning. Oxford, UK: Routledge.

Valenza, J. K., & Stephens, W. (2012). Reading Remixed. Educational Leadership, 69(6), 75-78. Retrieved from http://www. ebscohost.com