The world is changing before our eyes. I have previously expounded upon Information society and the literacy that is required in order to engage with this new society, so will not go on about that now. As teachers we can see the declining literacy ability of our students. We can see their lack of engagement and motivation. We know that this disengagement and apathy leads to poor behaviour within the classroom and consequently, poor life choices externally. Many students fall through this gap, citing boredom and disconnection to the school paradigm. This is even more true for low achieving students and or students in low socio-economic zones, where education is paramount to break generational cycles of dysfunction. Some schools focus their teaching and learning to address standardised testing (Kuhlthau et al., 2015). Whilst those schools may test high, their students struggle to translate their learning to an out of school context. As teachers we are frustrated and hamstrung by the politics of school.

Guided inquiry is a method of teaching and learning that has changed how students learn. Rather than a behaviourist method with stand alone teacher, GI promotes a constructivist team approach to teaching practices (Garrison & FitzGerald, 2016). This style of pedagogy promotes students to gain a deep understanding of the curriculum content and learn valuable skills in the process (Kuhlthau et al., 2015). The benefit is its fluid nature and this allows a flexible approach to learning which can be applied for all abilities and styles, as it seeks to explicitly teach skills rather than content. This is simply because skills are transferable and therefore of a higher value to both students and teachers. After all, in this information age, everyone can find out anything, provided they have the skills to do so.

A guided inquiry teaching and learning activity is designed to engage students in the content using their own intrinsic motivation (Maniotes, 2019). By utilising the 3rd space of learning, teachers can challenge students to connect to the curriculum content. This connection, based upon a constructivist ideology, allows students to question, explore and formulate new ideas based upon their own knowledge and perceptions (Kuhlthau et al., 2015, p.4). The learning itself is involves students finding and using a variety of information, to address an aspect of the content through an inquiry approach. During this process, students pose questions, make decisions, develop areas of expertise and learn life long skills (Kuhlthau et al., 2015, p4). As an educator there are two steps to GI. The first step is to apply the GI design framework when creating units of inquiry. These units incorporate curriculum content, literacy goals and information literacy concepts (Kuhlthau et.al,, 2015) and have specific learning goals as well as skills that will be addressed during the activity. The second step is to guide students through this learning with interventions, assessments and strategies (Kuhthau et al, 2015). It is quite common for teachers to explicitly teach ‘just in time’ skills during this process as teaching them any earlier usually has less relevance to them (Maniotes, 2019).

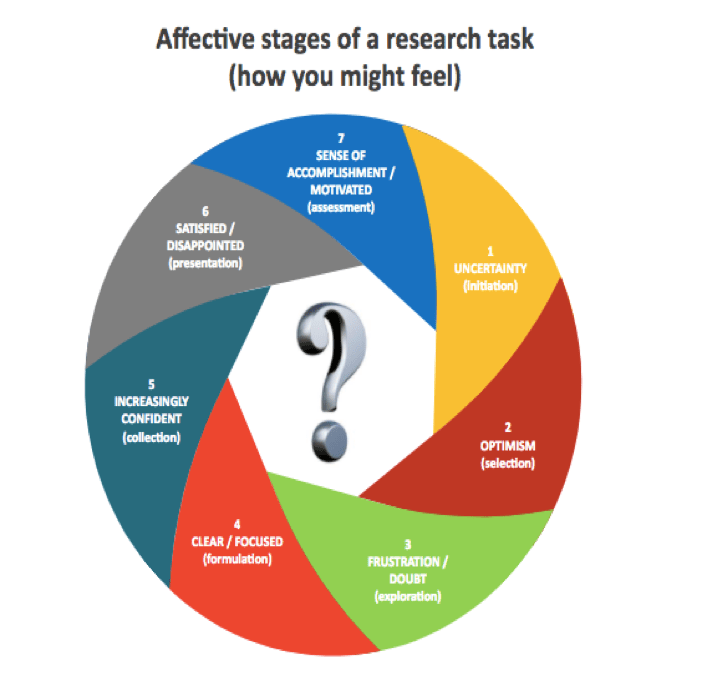

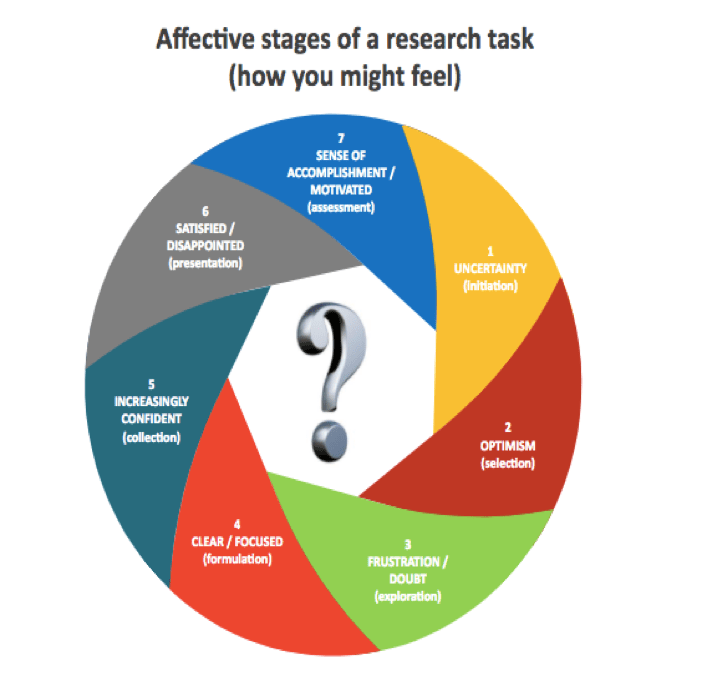

There are seven stages in GID unit. The stages go from an introduction phase through immersive, gathering, creative and sharing. As students progress through these stages they develop a whole range of skills and undergo a variety of emotional stress. It is this emotional stress and achievement over stress that assists with overall competence and self esteem. This figure shows the changing affective stages of an inquiry task.

Inquiry learning has many forms including project based learning; blended learning, International Baccalaureate programs and expeditionary learning. In Australia there are several IL models including Herring’s 2004 PLUS, NSW information search process, Newman’s 2014 iLEARN and Big6. But the superior form of inquiry learning is Guided inquiry design as it has a research based framework to substantiate its method of practice and the design understands the importance of affect in student behaviour. This affect is important to understand as it indicates to educators where motivation is and where guiding becomes important.

Whilst students are guided through the project, they get to pose their own question and explore ideas. This posing of question, is formulated from their own experiences, reflection and understanding. It acknowledges their learning is valid and promotes self esteem and self efficacy. Guidance can be tailored to individual students needs thus allowing for differentiation. As this process is a collaborative, students work with their peers in creating and investigating together. This sense of ownership and accomplishment leads to independence, expertise and competence (Kuhthau et al., 2015). Unfortunately, like all skills based learning, regular practice is required to maintain competency. Kong (2014) points out that classroom integration of IL leads to an increase in competency. Therefore, GI needs to be part of the learning and teaching across all grades and curriculum. It cannot be taught as a single subject in an ad hoc method as information literacy is cumulative (Lupton, 2014).

One of the many positives of Inquiry learning is that it promotes critical thinking skills (CCT). CCT, as part of the Australian curriculum’s general capabilities, needs to be embedded in teaching and learning practices. These skills are essential for participation in modern society. Within inquiry learning – CCT assists students in five major components. Curriculum content, information literacy, learning how to learn, literacy competence and social skills (Kuhlthau and Maniotes, 2010, p.19; Kong, 2014, p.2). All these skills are interwoven throughout the whole activity and an educator can choose which skill to assess at any given time.

The other interesting aspect of GI design unit is that the task comes halfway into the unit. Unlike current pedagogical practices where students get given a summative task at the beginning of the unit and then ‘do what is necessary’ and submit it a few weeks later. Inquiry tasks take students on an exploration of the unit. They are immersed in the unit of work either with field trips or excursions. They browse broadly among the literature, gaining various perspectives BEFORE the question is even posed. This means that when the question is posed by the student is truly authentic (Maniotes & Kuhlthau, 2014). It comes from what they DON’T know about a topic, rather than a regurgitation of facts. This process forces student to engage with the unit of work or they simply become mired in an information overload. This information overload occurs commonly outside school, where adults of all backgrounds, refuse to participate with something because they do not know or understand it. GI teaches students how to persevere and understand what the information is saying.

Collaboration is key to guided inquiry for both teachers and students. As the creation and implementation of GI units is multifaceted and complex, a team of teachers is required (Kuhlthau & Maniotes 2010). Ideally, this unit has three teachers co-creating the unit with additional experts involved as required. This team approach has the benefit of collaborative learning, in that many minds are better than one. It also models to students how collaboration occurs in the workspace. Students use the teaching team as role models for their interactions with their peers. These interpersonal skills are essential.

Figure -1 – KUHLTHAU, MANIOTES, CASPARI, 2012

The genius behind GI is that it is based up the information search process model which compares feelings, thoughts and actions of students as they progress through the unit. This understanding of student’s behaviour is of great insight to the educator. Teachers can predict when students are suffering from confusion and doubt and assist them in finding their way. I am musing if Marcia’s work on Erik Erikson’s theory of identity development is related to this process. After all, Erikson’s theory about adolescents facing moments of crisis and their response to the crisis shapes their identity. So theoretically, students who have their moment of crisis during an inquiry task move through to identity achievement, in that they have made a commitment to a value or role (David, 2014). Then once they have formulated a question or concept, students feel a sense of confidence, a sense of purpose. This sense of purpose and confidence translates to other aspects of learning and thus builds self efficacy.

The problem with the Australian curriculum is that IL is not embedded within and across the curriculum in all KLAs. Information literacy is cumulative. To have an IL education, sustainable development is required across all years and areas of study. It is should be part of the content, structure and sequence of learning; and definitely not the outcome of a single subject (Lupton, 2014). There has been some attempt by Bonanno & Fitgerald (2014) to map the Australian curriculum to the Guided inquiry design by Kuhlthau, Maniotes & Caspari (2012). The scope and sequence suggests the introduction of inquiry skills, which could be adapted throughout the curriculum. Lupton (2014) correctly surmised that inquiry strands are only currently within science, history and geography KLAs. Whereas Bonanno & Fitzgerald (2014) try to extend those skills in different areas of the curriculum. This is definitely possible as these ‘skills’ are transferable and there is no reason why one can pose a question in History that leads to an insightful understanding of the unit, but cannot do the same in math.

In summary, GI units of work are designed with the student in mind. They are student centred and place the onus of learning upon the student rather than the teacher. This is a seismic shift in pedagogy from a behaviourist to constructivist perspective. Students will engage with content if it is in their third space. They will commit to a task if they have a vested interest in the outcomes. They will learn more in collaborative groups. Mostly, they will work at their level of cognition and thus achieve a sense of accomplishment when the task is completed. We talk a great deal about student centred learning, about making the student the centre of the pedagogy. Well… lets just do it then.

Bonanno, K. with Fitzgerald, L. (2014) F-10 inquiry skills scope and sequence, and F-10 core skills and tools. Eduwebinar Pty Ltd.

David, L., (2014) “Identity Status Theory (Marcia),” in Learning Theories. Retrieved from https://www.learning-theories.com/identity-status-theory-marcia.html.

Garrison, K., and FitzGerald, L., (2016) ‘It’s like stickers in your brain’: Using the guided inquiry process to support lifelong learning skills in an Australian school library. A school library built for the digital age.

Kuhlthau, C., and Maniotes, L., (2010) Building guided inquiry teams for 21st century learners. ZZ School library monthly. Volume 26: 5.

Kuhlthau, C., Maniotes, L. & Caspari, A. (2012) Guided inquiry design: A framework for inquiry in your school. Libraries Unlimited.

Kuhthau, C., Maniotes, L., and Caspari, A., (2015) Guided inquiry: learning in the 21st century. 2nd Edition. Libraries unlimited, USA.

Maniotes, L., and Kuhlthau, C., (2014) Making the shift. Volume 43:2.

Lupton, M.(2014) Inquiry skills in the Australian Curriculum v6, Access, November

Maniotes, L., (2019) Guided Inquiry Design: Creating curious inquirers. SYBA Academy workshop. Sydney

Walton, G., Cleland, J., (2016) Information literacy. Empowerment or reproduction in practice? A discourse analysis approach. Journal of Documentation, Vol. 73 Issue: 4, pp.582-594, https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-04-2015-0048